Grey seals are getting caught in fishing nets. Lynn Batchelor- Browning/Shutterstock

Grey seals are getting caught in fishing nets. Lynn Batchelor- Browning/ShutterstockHundreds of thousands of marine animals are killed every year after becoming accidentally caught in commercial fishing nets. Sharks, skates and rays are at particular risk, alongside turtles, seals, whales and dolphins, many of which are endangered.

Much of this problem comes down to the design of fishing nets and how they are used. Particularly damaging are tangle nets, which typically use large mesh sizes and large amounts of slack that can indiscriminately catch anything that crosses their path. They are also typically left in the water for long periods and only checked every one to ten days.

A new four-year study from Ireland's national Marine Institute highlights the particular problem the nets are causing in Ireland. Legally protected seals, for instance, are regularly caught in this type of net, widely used by the Irish fishing industry including in the country's only marine national park.

Tangle nets were first introduced to Ireland in the early 1970s. This was to help boost the competitiveness of the Irish crayfish fishing sector and provide an alternative method to the traditional pot-based method that was used up to that point.

But tangle nets are known to potentially harm a variety of species. The estimated impact from the latest report (covering 2021-2024) about what the nets had caught was stark:

• 1,161 nationally protected grey seals

• 81 critically endangered angel sharks

• 1,712 critically endangered flapper skate

• 532 critically endangered tope sharks

Other species caught included the endangered white skate and undulate ray, as well as rarer records of common and Risso dolphins. Catches varied throughout the study region, and included Ireland's marine national park in County Kerry. It is unclear whether similar numbers are seen in other fishing areas throughout Ireland.

The report argues for the reduction of these accidental catches to "safe biological limits", but acknowledges that there probably is no safe limit for several of the shark and skate species given their conservation status and their approach to reproduction.

The documented numbers of catches is particularly concerning for the species' designated as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This classification stipulates an extremely high risk of extinction in the immediate future. Unlike many bony fish such as cod, tuna and salmon, sharks, skates and rays tend to mature slowly (often at more than ten years of age), have long gestation periods, and only produce a few young every year or two.

Rays and sharks are getting entangled in fishing nets.This makes it very difficult for them to recover if anything causes their populations to decline. The angel shark is a good example - once widespread throughout the north-east Atlantic, it has suffered drastic declines across its range, and the species is now locally extinct throughout much of Europe.

There are few remaining strongholds for the species, but County Kerry is one of the last northerly refuges for angel sharks. With so few left in the wild, numbers caught in Ireland's tangle net fishery are a significant concern at a global level.

Fisheries at a turning point?Irish commercial fishers are facing a challenging future, with a number of recent restrictions to activities and quotas creating severe pressure on numerous businesses and communities around Ireland , and closing the crayfish fishery would be another blow.

But there is a suitable and straightforward low-impact alternative to the tangle net, which is to fully return to the traditional pot fishery to target crayfish.

Currently in Ireland some fishers still use these pots, and others a combination of pots and nets. Pots are typically netted, baited cages with a narrow-funneled opening designed to only catch the target species with a minimal footprint when landing on the seabed and low risk of harm to the endangered and protected species documented in the Kerry report.

The report clearly states the urgent need of phasing out tangle nets, and highlights an upcoming Marine Institute report focusing on economic considerations supporting a complete switch from nets to pots. The current report suggests this is the "optimum solution". And it adds that trials using the pots showed equivalent catches.

Fishing is an integral part of Irish culture, and the need for a fair transition with appropriate support is repeatedly highlighted as essential for effective marine conservation.

What happens next in Kerry is probably going to be influenced by proposed legislation relating to how Ireland's marine landscape is managed. The potential introduction of the Marine Protected Area and Nature Restoration laws, currently being debated, are aimed at protecting and restoring marine biodiversity, and may soon change how fishing is carried out in Irish waters.

Examples from around the world show that it is possible to change the type of fishing nets used to protect marine life. Gillnets (which capture fish by entangling then around the gills) have been almost completely phased out in Australia's Great Barrier Reef marine park due to risks to animals including dolphins and turtles. Large scale drifting gillnets were banned in the European Union more than 20 years ago due to similar concerns.

The deaths of the world's most sensitive marine animals documented in the tangle net report highlight the urgency of how fishing needs to change globally, while also protecting the livelihoods of an industry important to coastal communities.

Nicholas Payne receives funding from Ireland's Marine Institute to study the ecology of sharks and rays. He is also a council member for the British Society of the British Isles

Louise Overy has received funding from National Parks and Wildlife Service for ecological research purposes and is a coordinator at the Irish Elasmobranch Group and Project lead of Angel Shark Project: Ireland.

Chris Homer/Shutterstock

Chris Homer/ShutterstockWhile floods are becoming more frequent in recent years, you should still be able to buy reasonably priced home insurance. That reassurance exists largely because of Flood Re. Launched in 2016, Flood Re is a national public-private reinsurance scheme that prevents many properties from being priced out of cover.

But the Flood Re scheme is a temporary fix that's due to end in 2039, on the assumption that flood risk will fall and the market can move back towards more risk-reflective pricing. As financial experts, we're worried that the UK may not be able to adapt its infrastructure and systems to climate change fast enough.

The success of the Flood Re scheme hinges on a shared contract between government, homeowners and insurers. Government has to cut risk through investment and delivery. Homeowners reduce damage by building back better and avoiding preventable exposure. And insurers must increase prices of premiums to better represent the climate risk but not so fast that cover becomes unaffordable.

If premiums rise too quickly, fewer households will stay insured and the ability to socialise risks across a large pool will not be possible.

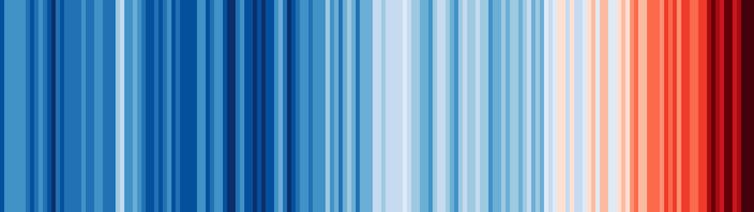

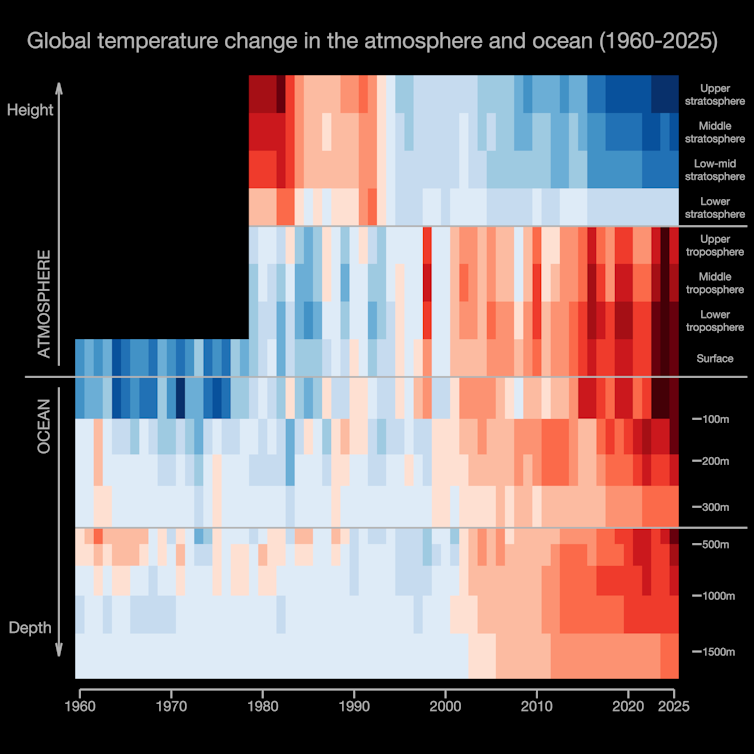

The scale of the challenge is already clear. Flood Re was designed when a global temperature rise of 1.5°C still felt achievable and a 2°C increase should be a hard limit.

Climate change has accelerated since then. By around 2050, around 8 million properties in England, roughly one in four, could be at flood risk.

The House of Commons public accounts committee warns that deterioration in existing defences has left around 203,000 properties without reliable protection, while the government aims to protect 200,000 more by 2027. Labour's target to deliver 1.5 million new homes in England by 2029 risks adding pressure by pushing development onto cheaper land that's at greater risk of flooding.

Many countries intervene to support insurance for disasters such as floods and storms, but few put a firm end date on that support. For example, The US National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was created to provide affordable flood insurance and to reduce future damage by discouraging development in high-risk floodplains.

In practice, repeated extreme weather has left the NFIP in debt and subsidised premiums have weakened incentives to avoid building in flood-prone areas. Although the NFIP is regularly renewed by the US Congress, its long-term sustainability remains uncertain.

France's catastrophes naturelles scheme (CAT-NAT) covers natural disaster losses that private insurers struggle to price, funded by a national surcharge. Rising losses from more frequent and severe disasters are straining the model, so the surcharge increased from 12% to 20% in January 2025. That raises a hard question: how can the system stay fair as the cost of disasters keeps climbing?

Preparing for post-2039Our ongoing research suggests flood-related volatility can amplify financial stress and uncertainty. The choice is not simply between keeping Flood Re forever or ending the scheme. The real question is whether the UK can use the time Flood Re is buying to reduce risk fast enough to make a fair transition possible by 2039.

That is why progress needs to be visible and measurable in five areas.

First, as demonstrated by recent updates in England and Wales, flood maps and modelling must reflect current conditions and future climate risk, with updates that keep pace with changes to the drivers of flood risk whether that be from heavy rainfall or rivers and the sea.

The Flood Re scheme is a temporary fix, not a long-term strategy.

Martin Charles Hatch/Shutterstock

The Flood Re scheme is a temporary fix, not a long-term strategy.

Martin Charles Hatch/Shutterstock

Second, governance must be joined up, with clear responsibilities and minimum coordination standards across agencies for rivers, surface water, drainage and sewers. Better collaboration would help to resolve misalignments in major capital programmes across risk management authorities.

Third, drainage and surface water management must be strengthened, with clear rules and long-term maintenance so new development does not add to flood and sewer risk.

Also, every tool in the box should be used to increase investment in flood risk reduction and to enhance maintenance. The benefits of flood protection should be made transparent to insurers and fed into catastrophe models.

Finally, a clear Flood Re future must be shaped together by planners, insurers and flood authorities. This will help set a shared standard for flood risk management.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Neil Gunn works and consults for Willis Towers Watson and also owns some shares in that company While the Willis research network supports scientific research through for example direct grants and in kind support, it benefits from schemes like CDTs which are supported by government funding

Dalu Zhang and Meilan Yan do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

NadyGinzburg/Shutterstock

NadyGinzburg/ShutterstockClimate change is usually assessed in scientific terms - rising temperatures, sea levels and carbon emissions. But increasingly, it can also be measured in household bills - higher insurance premiums, steeper energy charges and growing costs to protect homes, travel and health. So when US President Donald Trump said recently that abandoning a key government ruling on greenhouse gases would make cars cheaper for Americans, he was focusing on a tiny piece of a huge picture.

That is because climate change is not a local problem that hits one place at a time. It is increasingly a widespread financial risk, pushing on several parts of household finances at once. When risks become systemic, people cannot simply "insure it away" or plan around it.

When Trump announced he was revoking the US's 2009 "endangerment finding", which set out how greenhouse gas buildup harms human health and wellbeing, he said the move would save Americans "trillions of dollars".

But climate change shows up directly in household budgets as pressures converge. These pressures could include insurance becoming unaffordable or even unavailable, which can then have knock-on effects on property values. On top of that, utility costs can creep up, wages may become less reliable, and retirement savings are exposed to climate-driven shocks.

For many families, their home is their largest financial asset. But climate risk is increasingly being priced into property markets. Research suggests that in the United States, homes exposed to flood risk may be overvalued by between US$121 billion and US$237 billion (£89 billion and £174 billion). The First Street Foundation, an independent climate risk research organisation, estimates that climate risk could wipe out as much as US$1.47 trillion in US home values by 2055.

In the UK, evidence shows that house prices in English postcodes affected by inland flooding fell by an average of 25% compared with similar non-flooded areas. Coastal flooding in England has been associated with price reductions of roughly 21%. The Environment Agency estimates that one in four homes in England could be at risk of flooding by the middle of the century.

Insurance is expensive - or unavailableMany governments have tried to prevent climate risk from pricing people out of insurance by creating schemes of last resort. These government-backed initiatives keep policies available when the market would otherwise withdraw. But this safety net is now under growing financial strain.

In the US, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has accumulated more than US$22 billion in debt to the US Treasury after repeated borrowing to cover claims.

Meanwhile, in the UK, Flood Re was designed to buy time for adaptation while keeping flood insurance affordable. Yet rising claims have driven up reinsurance costs by around £100 million for 2025/26. France also had to increase the mandatory surcharge on its national "Cat Nat" natural catastrophe scheme from 12% to 20% from January 2025 to maintain financial stability.

Climate change affects households even if they do not own property. As utilities invest in stronger, more resilient infrastructure, those costs are usually recovered through higher standing charges and tariffs. In other words, the price of adaptation is quietly passed on through monthly bills. In California, for example, wildfire-related grid upgrades added 7% to nearly 13% to household energy bills in 2023.

The same logic applies to cars. Rolling back US vehicle emissions rules is being sold to American consumers as cutting US$2,400 off the price of a new car. But that sum isn't a cheque to ordinary Americans. Carmakers are not required to pass the saving on, petrol drivers can end up paying more at the pump, and EVs still come with a high upfront price tag.

In reality, the figure is best understood as an estimated reduction in manufacturers' compliance costs, not a guaranteed discount at the dealership.

Climate change doesn't only put pressure on household budgets. It also threatens the thing many families rely on most: a steady pay cheque. Large parts of the economy worldwide still depend on work that happens outdoors from agriculture and construction to tourism, deliveries and logistics. The 2022 California drought cost farming around US$1.7 billion in revenue and nearly 12,000 job losses.

There are also direct health costs. The International Labour Organization warns that climate hazards expose workers to a "cocktail" of risks, including heat stress, air pollution, ultraviolet radiation and physical injury.

It estimates that 2.4 billion workers around the world could be exposed to climate-related health hazards. Excessive heat already affects about 70% of the global workforce, contributing to 18,970 work-related deaths and roughly 23 million workplace injuries each year.

Climate change is increasingly seen by regulators and investors as a systemic risk that can undermine the pensions people rely on in retirement. Risk management technology firm Ortec Finance warns that failing to transition to a low-carbon global economy could reduce pension fund returns worldwide by around 33% by 2050.

Physical risks (floods, heatwaves and storms) can damage assets and disrupt productivity. Transition risks (policy shifts and sudden repricing of carbon-intensive assets) can hit valuations. Together, they weaken the performance of equities, property and infrastructure.

When climate risk is systemic, there's no bargain to be made: short-term "savings" don't reduce household costs, they are repaid soon through higher bills. Rather than driving up the cost of living, climate policy helps to stop climate shocks from raising prices even faster.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Mount Faloria rises above Cortina d'Ampezzo, one of the host towns for the 2026 Winter Olympics. kallerna / Wikimedia, CC BY

Mount Faloria rises above Cortina d'Ampezzo, one of the host towns for the 2026 Winter Olympics. kallerna / Wikimedia, CC BYItaly's 2026 Winter Olympics have been described as the most regionally distributed Winter Games ever staged. Events are spread across more than 22,000 km², taking in Milan, as well as the towns of Cortina d'Ampezzo, Valtellina, Val di Fiemme and Livigno in the Alps.

Geographical dispersion is not entirely new. In 1956, the equestrian events of the Melbourne summer Olympics were actually held 15,500 km away, in Stockholm, Sweden, five months before the rest of the games. This was due to Australia's quarantine rules. More recently, surfing during Paris 2024 was done in Tahiti, 15,727km from the French capital. The competition was duly labelled "most distant Olympic event ever".

As a sports management specialist with a human geography background, my research looks at how new spatial solutions and distribution of sport activities and events across a territory increases their sustainability and long-term viability. What distinguishes Milano-Cortina is the way it has been organised across the regions of Lombardy, Veneto and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano. This represents a strategic shift towards what geographers would term a "dispersed, multinodal model". More than 90% of the venues being used already existed or are temporary. The goal is to reduce construction, minimise environmental impact and reduce any long-term maintenance burdens. In other words, the games have adapted to the territory rather than reshaping it.

Learning from past GamesThe approach adopted for this year's games indicates that national organising committees, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC), are willing to adapt. Research shows such a shift is long overdue.

Olympic planning has long involved sustainability rhetoric. Recent reforms emphasise reduced environmental footprints and the use of existing facilities. Yet, events including the Paris 2024 summer games, have been accused of greenwashing.

Italy's own experience, during the Torino 2006 winter games, highlighted the risks of overbuilding in fragile mountain environments. Many of those purpose-built facilities faced long-term operational and ecological challenges.

Organisers are getting much better at designing flexible venues that can be adapted by the host city for use after the event. In Paris, 95% of the venues were either pre-existing or temporary. The games notably transformed the river Seine into a venue for the opening ceremony and aquatic events. It was expensive to pull off, but as a demonstration of public space reuse and long-term urban ecological investment, it was symbolically powerful. The Place de la Concorde was also converted into a temporary street-sport hub. This showcased how urban environments can host dynamic youth events that blend competition with city life.

Winter games, of course, face different constraints. Where summer hosts can absorb scale, winter hosts rely on natural landscapes that are already under severe climatic pressure. This increases both the stakes and the complexity of sustainable design.

On one hand, spreading events across regions makes them more accessible to multiple communities. It involves more municipalities and regional bodies in planning, implementation, and legacy building, which in turn can foster stronger local engagement and a more distributed sense of ownership.

On the other hand, the model requires robust coordination between diverse actors. It also poses the risk of a fragmented Olympic identity. And it makes media coverage more complex. While this drives innovation in terms of hybrid reporting tools and local storytelling, it can lead to platforms prioritising some events over others.

The transport challengeThe most significant sustainability challenge remains transport. A dispersed model inherently requires athletes, officials, media and spectators to travel more between places. According to the IOC, Milano-Cortina 2026 relies heavily on trains and shuttle systems to minimise private car use, with the goal of reducing car use by 20%, compared to Torino 2006.

Overall travel demand is, however, more complex. A 2022 study on preparations for Milan-Cortina, showed that the larger the host territory, the more complex its mobility planning. Participants still have to get to events and the people who live there, meanwhile, "still expect to inherit benefits from any investments made". Infrastructure upgrades, from rail modernisation to enhanced alpine transit, are duly central to the 2026 games' legacy strategy.

Long-distance spectator travel, in particular, remains a huge factor in the games' carbon footprint, whether the event is geographically concentrated or dispersed. Research published by the French government showed that international travel accounted for almost 50% of the Paris 2024 summer games's carbon footprint.

In sum, from a resource, climate and environmental perspective, Olympic winter games are not justifiable. They inevitably intrude into the natural landscape and despite all sustainability-led reforms, implementation on the ground is spotty. Milano-Cortina 2026 has included some infrastructure projects which reportedly lack environmental assessments or long‑term utility. To what extent this will be offset by the benefits of its geographical dispersion model remains to be determined.

But the public loves them. The Milano-Cortina 2026 approach signals a vital willingness to adapt. As snowpacks retreat, temperatures rise and young people scrutinise what leaders are doing to the environment with ever greater acuity, this might well be the only thing keeping this event alive.

Karin Book does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Lillac/Shutterstock

Lillac/ShutterstockWhen we dream of landscapes, we might imagine rolling valleys or rugged mountains. But there is a whole landscape hidden from human view: the secret world of the seafloor.

Half of Earth's oceans are more than 3.2km deep. Beneath them lie cavernous plains untouched by sunlight, vast gaping trenches made by Earth's tectonic plates shifting, and ranges of underwater mountains on which no human has ever set foot.

We have better maps of the surface of the Moon than of these secret landscapes of the seafloor. However, the international 2030 seafloor project has an ambitious aim: to create a definitive map of our oceans.

To date, despite huge efforts, less than a third of our oceans have been fully mapped. But one unexpected way to help understand what's beneath the surface may come from a project one of us (Jessica) works on called Mermaid - a mission that was originally designed to detect earthquakes.

Earth's deepest region, the Marianas Trench, plunges 2km deeper than Mount Everest is high. But along the ocean floors, there are also tens of thousands of mountains which rise upwards: seamounts. Traditionally mapped by ships, modern satellite missions are revealing more information about these - indeed, it's estimated that the number of known seamounts may double thanks to these space-based observations.

What's on the seafloor?The seafloor is, typically, geologically much younger than the continents that make up Earth's dry land. New rock is formed at mid-ocean ridges that snake across the Earth's major oceans. These host hydrothermal vents where conditions are so different to the surface that astrobiologists compare them to other planets.

While the major mid-ocean ridges were being mapped 70 years ago, other underwater mountains dotted across the oceans are much less well known. These seamounts are often of volcanic origin and can grow so large that their summits escape the ocean, becoming islands. From its summit to its base at the floor of the Pacific Ocean, for example, Hawaii's dormant volcano Mauna Kea is taller than Everest.

Many seamounts are topped with coral reefs which have drowned as they sank too far below the ocean surface. But these drowned reefs remain important hotspots of biological diversity in our oceans, hosting both bottom-dwelling and swimming lifeforms.

A small number of seamounts are currently growing - some of which will eventually become Earth's newest islands. For example, if Vailuluʻu seamount keeps growing, it will become the newest island in the Samoan Archipelago.

New seamounts are still being discovered. It may seem odd to miss a mountain when you're making a map of a landscape, but they can be hard to find below the ocean.

How are scientists trying to map the seafloor?Traditional methods of mapping the seafloor involve using ships to estimate the ocean's depth. New advances involve autonomous underwater vehicles, which can estimate seafloor depth, and satellite missions, which can "feel" the changes in gravity caused by seamounts.

Another indirect approach comes from EarthScope-Oceans, the consortium which operates Mermaid - a project sending small robots deep below the ocean surface to detect earthquakes.

Mermaid robots float at depths of about 1.5km, where the water pressure is 150 times that at the surface. These robots listen for pressure waves generated by signals from distant earthquakes in Earth's solid interior. Since 2018, one fleet of Mermaid sensors, deployed in the South Pacific Ocean, has recorded thousands of waves associated with earthquakes.

There is so much of the oceans left to explore.

divedog/Shutterstock

There is so much of the oceans left to explore.

divedog/Shutterstock

But in 2022, scientists realised that Mermaid robots had recorded something else: waves travelling through the ocean from a volcano. The violent underwater eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, a South Pacific underwater volcano, was the biggest in nearly 150 years. As well as causing volcanic lightning and sending plumes of ash tens of kilometres into the sky, the eruptions sent pressure waves into the waters of the Pacific.

Mermaid sensors heard these waves thousands of kilometres away from the volcano. At some of these sensors - scattered across the ocean over vast distances - the sounds were virtually identical. But where the sounds were different, recent research has revealed that seamounts were often to blame.

Seamounts block energy travelling through the ocean. This opens the prospect of using pressure waves from underwater explosions and eruptions to listen for "acoustic shadows" caused by unknown seamounts. In other words, finding seamounts by listening to the pressure waves they interrupt.

The future of deep ocean landscapesAs we explore the seafloor, human impact on it will become more apparent. While some researchers are discovering exotic lifeforms such as deep-sea snailfish in the oceans' deep trenches, others are detecting signs of microplastic waste in trench-dwellers such as deep sea scavenging amphipods (which look a bit like shrimp).

The seafloor is rich in mineral deposits, many of which are elusive on land - including minerals critical for battery construction. For example, polymetallic nodules rich in rare earth elements litter the ocean floor.

Areas of elevated seafloor like seamounts are especially likely to host cobalt-rich deposits - one of many critical minerals needed for the green energy transition and to meet UN sustainability goals.

However, exploration and active mining in the delicate ecosystems that surround these hidden worlds is controversial, because of the harm it can cause.

If we want to know where resources lie - and where the ocean floor most needs our protection - it is vital we understand the landscapes of the seafloor.

Jessica Irving has received funding from the National Science Foundation to work with MERMAID. She is a member of the Earthscope Oceans Science Committee and was involved in the research study described in this article. Dr Irving acknowledges useful input from Dr Joel Simon of Bathymetrix, who led the MERMAID research into the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha'apai eruption.

Elizabeth Day is part of the Membership Committee of the Royal Astronomical Society and also sits on the Royal Astronomical Society's Education and Outreach grants panel.

The Bafta film awards are brilliant at making film feel like it matters. The clothes, the cameras, the applause, the shared cultural moment. That spectacle is the point.

But it also has a climate shadow. Not just from the night itself, but from the behaviour it effectively rewards and normalises in the weeks around it.

Here's the awkward truth: the biggest carbon impact in film and TV isn't the red carpet. It's travel. And awards season is, in effect, a celebration of travel.

Industry data backs this up. Bafta Albert is the film and TV industry's sustainability organisation which supports productions to measure and reduce their environmental impact.

It highlights that productions that report their emissions find that around 65% come from travel and transport, with flights alone accounting for roughly 30% of the total. Energy use - mainly from studios and on-location generators - makes up about a fifth, while materials and waste account for the rest. In short: the carbon is mostly off camera.

So what about the Bafta film awards themselves?

Bafta has made visible efforts to reduce the negative environmental effects of the ceremony. This year, organisers are using diesel-free generators at the venue and green electricity tariffs at Royal Festival Hall in London, plus reusing existing sets and props. Red meat won't feature on the menu and guests are encouraged to rewear or hire an outfit for the occasion.

A spokesperson for Bafta and Bafta Albert explained that the carbon emissions and the footprint of the awards have been measured and reduced using Bafta Albert resources and guidance. "Proactive steps taken this year include the use of [hydrotreated vegetable oil] HVO generators, hosting the awards at a venue also dedicated to reducing its own carbon emissions, encouraging sustainable travel, banning single use plastics, sustainable menus and minimising waste," they said.

Previous awards have been described as carbon neutral, with changes such as removing nominee goody bags and introducing vegan menu options. More recently, sustainability messaging has extended to catering and packaging choices.

These changes aren't meaningless. They're also the easiest things to photograph.

The problem is scale. If flights dominate emissions, then the biggest wins won't come from menus or outfits. They'll come from changing how people get there in the first place.

I research sustainability in film production, including how cinematography and production practices can reduce environmental impact, and one thing is clear: framing sustainability as removal or punishment rarely works. People resist. They dig in. Or they swing hard in the opposite direction.

At the same time, the glamour of awards season is precisely why people watch and pay attention. Strip that away entirely and the cultural power goes with it. The real challenge is finding a balance: keeping the spectacle while changing the behaviour it endorses.

One practical way to do this is to stop treating awards travel as an unfortunate side-effect and instead make it part of the event itself.

Read more: The hidden carbon cost of reality TV shows like The Traitors

Rather than dozens of individual long-haul flights - and, yes, sometimes private jets - designated flights from major hubs could be coordinated from places like Los Angeles, New York, Paris or Amsterdam. If you're attending, you take the shared flight. If you can't, you accept your award remotely, as people have done perfectly well in the past.

This wouldn't eliminate flying. But it would reduce per-person emissions, remove the prestige of flying separately and turn collective travel into something visible and intentional.

I've experienced this kind of shared travel firsthand. Years ago, flying back from a film shoot in Budapest, Hungary, I found myself on a completely ordinary commercial flight that happened to be carrying athletes travelling to London ahead of the 2012 Olympic Games.

There was press at the airport, excitement in the cabin and a palpable sense of shared purpose. These were people at the top of their fields, travelling together, not separately, on the same flight as everyone else. It didn't feel like a compromise. It felt anticipatory, slightly chaotic, yet collective.

This is not an unprecedented idea. Sport already does this. Politics does this. Even music tours do this. Film just pretends it can't.

During COVID, awards ceremonies and press circuits moved online or became hybrid events. It wasn't perfect, but it worked. Research comparing in-person and virtual international events shows that moving online can cut carbon footprints by around 94%, largely by removing travel. Awards aren't conferences, but the lesson is clear: if travel is the biggest source of emissions, reducing travel is the biggest lever.

Greenwash v real changeA simple test helps separate meaningful sustainability from greenwash. Does an action reduce high-emissions activities - flights, fuel, power, logistics - or does it mainly change how things look?

Carbon offsetting, for example, is often used to claim climate neutrality without changing underlying behaviour. But many offset schemes have been criticised as ineffective or misleading. The EU has moved to restrict environmental claims based on offsetting alone.

Flights are a big contributor to the environmental footprint of film awards.

Yusei/Shutterstock

Flights are a big contributor to the environmental footprint of film awards.

Yusei/Shutterstock

That doesn't mean nothing is happening. Bafta Albert's Accelerate 2025 roadmap is a UK-wide plan developed with broadcasters and streamers to cut film and TV emissions.

It focuses on cutting flights and encouraging train travel, cleaning up on-set power and changing production norms. This is being echoed by trade coverage calling for practical, immediate action to cut carbon emissions across the film and TV sector.

A spokesperson for Bafta and Bafta Albert stated: "There is a clear dedication to continually increasing the sustainability of the awards, behind the scenes, at the event itself and on screen."

Awards culture still matters. The Baftas don't produce most of the industry's emissions. But they help define what success looks like. If success looks like frantic long-haul travel and personal convenience, that becomes the aspiration. If it looks like coordinated travel, cleaner power and credible data, that becomes the norm.

So keep the glamour. Keep the ceremony. But redesign the signals. If we can make the journey part of the story, we might finally start shrinking the part of film's footprint that nobody sees - until the planet sends the bill.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Jack Shelbourn is a member of the Green Party of England and Wales.

MarcelClemens / shutterstock

MarcelClemens / shutterstockAs the Atlantic warms, many fish along the east coast of North America have moved northwards to keep within their preferred temperature range. Black sea bass, for instance, have shifted hundreds of miles up the coast.

In the Mediterranean, the picture is very different. Without an easy escape route towards the poles, many species are effectively trapped in a sea that is warming rapidly. Some native fish are even being replaced by more heat-tolerant species that have slipped in through the Suez Canal.

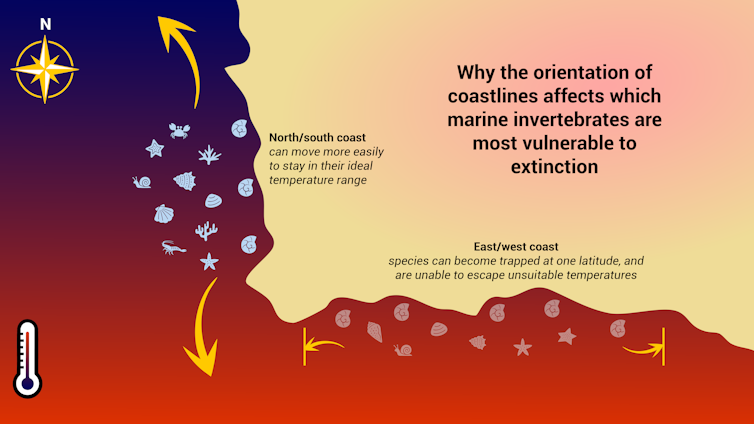

It's a process affecting coastal species around the world: without a continuous pathway to cooler waters, many are in trouble. Escape becomes difficult where coastlines run east-west or are broken into enclosed basins and islands. In these settings, species have to move huge distances just to gain a few degrees of latitude - the so-called "latitudinal trap".

It's also a process that has repeated throughout history. When we analysed 540 million years of fossil data for a recent study published in the journal Science, we found that species along east-west coastlines were more likely to go extinct than those with easier movement north-south.

Malanoski et al (2026) / Science

Malanoski et al (2026) / Science

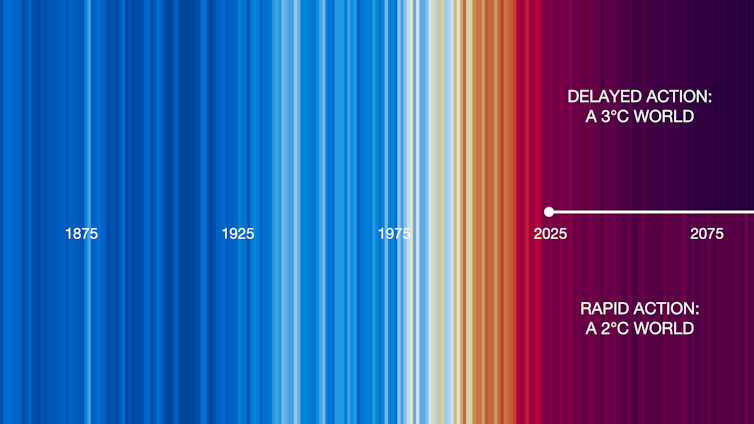

We hypothesised that the shape and orientation of coastlines could help species escape - or trap them. If coastlines provide direct, continuous pathways to move north or south, species should be able to better track shifting climates. But, where species have to travel a long way for minimal latitude gain, their extinction risk is raised during episodes of environmental change.

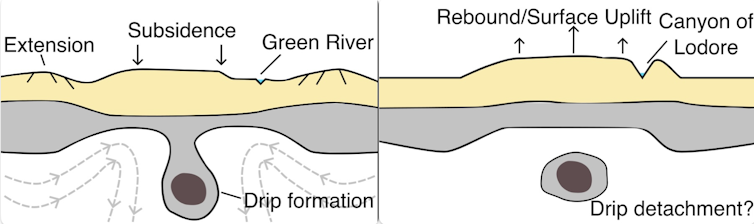

Coastlines themselves are not fixed. Over millions of years, plate tectonics rearrange continents, sometimes producing long north-south coasts, like those of the Americas today, and at other times sprawling east-west seaways such as during the Ordovician a bit over 400 million years ago.

This means climate shocks can produce very different extinction outcomes depending on the layout of continents at the time.

To test this hypothesis, we analysed fossil data for about 13,000 groups of related shallow-marine invertebrate species, such as clams, snails, sponges and starfish, spanning the last 540 million years. We then paired these records with reconstructions of ancient geography.

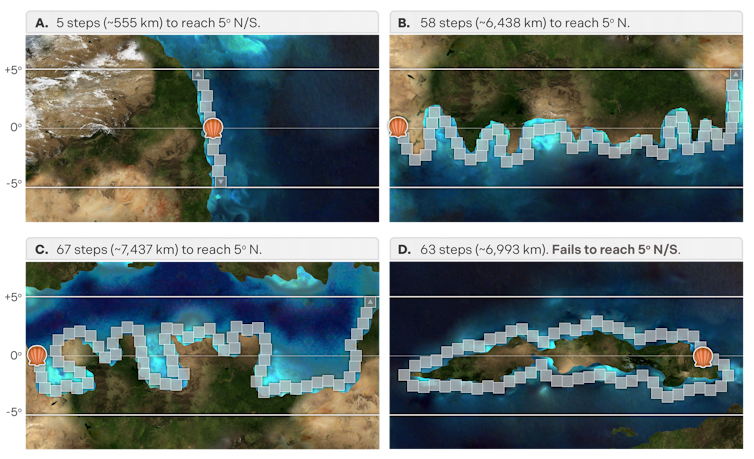

For each fossil, we estimated how difficult it would have been for that species to shift its latitude along shallow coastlines. We measured this as the shortest number of steps to travel 5°, 10°, or 15° latitude north or south. (For context, Great Britain covers about 9° from top to bottom). Short distances imply a relatively direct escape; long distances imply a long or maybe impossible escape route.

A 5° shift in latitude can be reached quickly along a simple north-south coastline (A), but requires much longer routes—or cannot be reached at all—along convoluted east-west margins (B), interior seaways (C), and islands (D).

Malanoski et al (2026) / Science

A 5° shift in latitude can be reached quickly along a simple north-south coastline (A), but requires much longer routes—or cannot be reached at all—along convoluted east-west margins (B), interior seaways (C), and islands (D).

Malanoski et al (2026) / Science

We found that, over the last 540 million years, extinction risk was consistently higher for marine animals with long escape routes.

Geography amplifies catastropheThis pattern intensified during Earth's five mass extinction events. In our models, species with longer distances showed increases in extinction risk of up to 400% during mass extinctions, compared with about 60% during other intervals, highlighting that geography becomes far more consequential when climate change intensifies.

Although our analyses focused on geologic timescales, our results help us understand how shallow marine species may respond to climate change today. Species living in the Mediterranean or the Gulf of Mexico or other regions with semi-enclosed geography, or around the margins of islands, may have more difficulty as the ocean warms.

Coastline geometry may matter less for species that are good at dispersing themselves, however, especially those that have a long planktonic larvae phase where they drift around the ocean before becoming fixed in place. The survival of those species depends more on factors like ocean currents than coastline orientation.

Estimating whether a species is at risk of extinction is typically done with reference to attributes such as body size or geographic range size. But our work shows that extinction risk also depends on geography. Survival during climate upheaval depends not only on a species' biology - but on whether the map itself offers an escape.

Erin Saupe receives funding from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the Leverhulme Trust.

Cooper Malanoski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Alive Color Stock/Shutterstock

Alive Color Stock/ShutterstockRecent investigations have uncovered forced labour in agricultural supply chains, illegal fishing feeding supermarket freezers, deforestation embedded in everyday food products, and unsafe conditions in factories producing "sustainable" fashion. These harms were not visible on labels. They surfaced only when journalists, whistleblowers or activists exposed them.

And when they did, something predictable happened. Consumers felt uneasy. Brands issued statements. Promises were made. The point is that the force that set change in motion was not regulation. It was consumers.

Discovering that an ordinary purchase may be tied to exploitation or environmental damage creates a jolt of personal responsibility. In our research, we found that when environmental consequences are clearly linked to people's own buying choices, many are willing to switch products — especially when credible alternatives exist.

But guilt is private. It nudges personal behaviour. It does not automatically reshape systems. The shift happens when private discomfort becomes public voice.

Consumers are often also the first to make hidden environmental harms visible. They post evidence on social media. They question corporate claims. They compare sustainability promises with independent reporting. They organise petitions, boycotts and review campaigns. By shining a spotlight on the truth, the scrutiny shifts from shoppers to brands.

That shift matters because modern brands depend on trust. Reputation is an asset. When sustainability claims are publicly challenged, credibility is at risk. Research in organisational behaviour shows that firms respond quickly to threats to legitimacy. Reputational damage affects customer loyalty, investor confidence and regulatory attention.

In many high-profile cases, supply chain reforms have followed intense public scrutiny rather than quiet compliance checks. Leaders may not act out of moral awakening — but they do act when inaction becomes costly to their reputation.

Consumers can trigger the emotional chain reaction. They feel guilt. They seek information. They speak collectively. That collective voice generates corporate shame.

Consumers have the power to demand more transparency from brands.

Stokkete/Shutterstock

Consumers have the power to demand more transparency from brands.

Stokkete/Shutterstock

Sustainability professor Mike Berners-Lee argues in his book A Climate of Truth that demanding honesty is one of the most powerful climate actions available to citizens. Raising standards of truthfulness in business and media changes incentives. When the gap between what companies say and what they do becomes visible, maintaining that gap becomes harder.

Our research explores how that visibility can be strengthened. The findings were clear. When environmental and social consequences are personalised and traceable, sustainability feels less distant. People see both their own role and the role of particular firms. That dual awareness encourages two responses: behavioural change driven by guilt and corporate accountability driven by shame.

Shame works because it is social. Brands care about how they are seen. When the negative environmental and social effects of supply chains can be publicly connected to named products, corporate narratives become contestable in real time.

Making supply chains socially visibleThe technology to improve transparency already exists. Companies track goods through logistics systems, supplier databases and digital product-tagging that collect detailed information about sourcing and production. The barrier is not data collection. It is disclosure.

Environmental indicators — carbon emissions, water use, land conversion risk, labour standards compliance — can be linked to products through QR codes or retail apps. Comparable reporting standards would ensure consistency. Simple digital interfaces would make information accessible. Social sharing tools would allow consumers to compare and discuss findings publicly.

Social media is crucial. It already enables workers, communities and campaigners to challenge corporate messaging. Integrating verified supply chain data into these spaces would shift transparency from crisis response to everyday expectation.

This strategy, with its behaviour change directive, could work more effectively than rules or green marketing campaigns alone.

Regulation is essential but often slow and uneven across borders. Marketing campaigns can highlight selective improvements while leaving deeper practices untouched. Transparency activated by collective consumer voice operates differently. It aligns emotional motivation with reputational consequence.

Consumers are not passive recipients of information. They are catalysts. By feeling the first twinge of guilt, asking harder questions and speaking together, they create the conditions under which companies experience shame. When shame threatens trust and market position, change becomes rational and inevitable.

Shame is uncomfortable. But when directed at opaque systems rather than consumers, it can be powerful. By demanding truth and making supply chains socially visible, consumers can push businesses towards greater transparency — and, ultimately, towards more sustainable practice.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Janet Godsell receives funding for the Interact Network+ from the Innovate UK Made Smarter Innovation Programme via the ESRC. She is affiliated with the World Economic Forum (WEF) Advanced Future Council for Advanced Manufacturing and Global Value Chains.

Nikolai Kazantsev receives funding from UKRI funded project "Resilience in Agrifood Systems Supply Chain Configuration Analytics Lab (Project ID: R1650GFS). He is a fellow of Clare Hall College, Cambridge.

After weeks of relentless rain and flooding, and even more forecast, 2025's droughts and hosepipe bans feel like ancient history. But they shouldn't.

The UK is increasingly caught between these wetter winters and warmer, drier summers. What if this year's summer brings water shortages again? The seemingly endless rainfall causing flooding across the UK right now could help solve future summer drought problems - if we capture it right.

The stakes are high in Speyside, home to around half of Scotland's malt whisky distilleries. They had to cope with 2025 being the UK's warmest and sunniest on record, where prolonged dry conditions led to widespread restrictions on water abstraction. Multiple distilleries were forced into temporary closures, costing the industry millions of pounds and highlighting just how vulnerable even Scotland's famously wet regions are to water scarcity.

Whisky production represents one of the UK's biggest industrial water users. Large quantities of water are required for the distilling process and the product itself, so understanding water conservation is both extremely important for the industry, and can also help others recognise the benefits.

If it was possible to retain this winter's rainfall and release it gradually when it was needed, the nation could become more resilient to both floods and droughts without building expensive new reservoirs.

Managing droughts with floodsAcross Speyside, they're testing ways to slow, store and steadily release water by working with the landscape rather than against it. Distillers have invested in leaky dams (small barriers built across temporary upland streams) to slow the flow of water during heavy rain and allow the rainwater to soak into soil and recharge groundwater.

Leaky dams hold the water at surface level as well helping it store underground. Water in the soil and deeper groundwater move through the subsurface much more slowly than over land - taking weeks or months rather than hours or days - which is why rivers still flow even after long dry spells.

Tromie river in Speyside.

Ondrej Zeleznik/Shutterstock

Tromie river in Speyside.

Ondrej Zeleznik/Shutterstock

There are other examples of useful interventions. Peatland restoration, wetland creation and tree planting all work by increasing temporary storage in the landscape and slowing the movement of water into rivers.

Research across upland catchment areas in Cumbria and West Yorkshire shows how the principles being tested in Speyside could translate to elsewhere. A large academic review of natural flood management evidence concluded that measures increasing water storage, slowing the flow of water over the land or enhancing soil structure can consistently reduce the peak level of a flood.

This growing body of evidence supports a simple but powerful idea: the UK and other countries could be more resilient to droughts and floods by redesigning landscapes to keep water around for longer.

Three lessons for the rest of the UK1. Design and location matter

Local factors and hydrology (the study of the movement and management of water) can determine what works best where. For example, planting trees "somewhere" delivers far less benefit than planting them in the right places, especially near rivers, near the source of the river, or where soil can absorb water.

2. Benefits must stack up or they won't be adopted

Leaky dams and other projects, such as tree planting, are relatively inexpensive, compared with traditionally engineered flood defences or having to deal with flood and drought consequences. They can deliver benefits at a fraction of the cost, while potentially also increasing biodiversity, soil health, carbon capture and improving water quality.

But there are trade-offs, which need to be assessed early. For example, in some cases, large-scale tree planting can also reduce summer water availability in already stressed catchment areas. Tree canopies can temporarily store water on the leaves, but if this water evaporates it doesn't return to the soil. Tree roots improve the soil so it absorbs and stores more water, but trees can also use more water. The net effects depend on factors such as climate, soil type and tree species.

3. Good governance will unlock funding

When water security has clear economic benefits, businesses are willing to engage. However, investment is not always private, and a recent review showed public funding is often fragmented, with inconsistent planning rules. Strengthening overall governance of these kind of schemes is essential, because farmers, businesses and landowners are far more likely to participate if they benefit.

Managing our landscapes appropriately won't stop all floods or prevent every drought, but it can make both less severe, while restoring habitats, supporting farming, and protecting industries that rely on dependable water supplies.

Every river carrying floodwater to the sea represents water that could be stored for drier months. Thinking ahead for what happens during heavy rains can be part of forward planning for more extreme weather in years to come.

Josie Geris receives funding from the Natural Environment Research Council, Royal Society, the Scottish Government via CREW (Scotland's Centre of Expertise for Waters), and Chivas Brothers.

Megan Klaar receives funding from the Natural Environment Research Council, The Leverhulme Trust and National Trust.

Setting sail from the busy port of Plymouth in Devon, the tall ship Pelican of London takes young people to sea, often for the first time.

During each nine-day voyage, the UK-based sailing trainees, who often come from socio-economically challenging backgrounds, become crew members. They not only learn the ropes (literally) but also engage in ocean science and stewardship activities.

As marine and outdoor education researchers, we wanted to find out whether mixing sail training and Steams (science, technology, engineering, art, mathematics and sustainability) activities can inspire young people to pursue a more ocean-focused career, and a long-term commitment to ocean care.

Research shows that a strong connection with the ocean can drive people to be active marine citizens. This means they take responsibility for ocean health not only in their own lives but as advocates for more sustainable interactions with the ocean.

Over the past year, we have worked with Charly Braungardt, head scientist with the charity Pelican of London, to create a new theory of how sail training with Steams activities can change the paths that trainees pursue.

Based on scientific evidence, our theory of change models how Steams activities can cause positive changes in personal development and knowledge and understanding of the ocean (known as ocean literacy). It shows how the voyages can develop trainees' strong connections with the ocean and encourage them to act responsibly towards it.

Tracking changeSurveys with the participants before and after the voyage, and six months later, measure any changes that occur - and how these persist. Through our evaluation, we're exploring how combining voyages with Steams activities can go beyond personal development to produce deep, long-lasting effects.

Our pilot study has already shown how the sail training and Steams combination helps to develop confidence, ocean literacy and ocean connections.

For example, the boost to self-esteem and feelings of capability that occur on board help young people develop their marine identity - the ocean becomes an important part of a person's sense of who they are. As one trainee put it: "I think the ocean is me and the ocean will and forever be part of me."

Swimming, sailing, even just building a sandcastle - the ocean benefits our physical and mental wellbeing. Curious about how a strong coastal connection helps drive marine conservation, scientists are diving in to investigate the power of blue health.

This article is part of a series, Vitamin Sea, exploring how the ocean can be enhanced by our interaction with it.

As crew members, trainees access a world and traditional culture largely unknown to them before the voyage. They learn to live with others in a confined space, working together in small teams to keep watch on 24-hour rotas.

Trainees are encouraged to step out of their comfort zone through activities such as climbing the rigging and swimming off the vessel. Our pilot evaluation found the voyages built the trainees' confidence and social skills, boosting self-esteem and feelings of capability.

One trainee said: "I've felt pretty disappointed in myself not committing to my education or only doing something with minimal effort. But after this voyage, I want to give it my all."

Read more: Five ways to inspire ocean connection: reflections from my 40-year marine ecology career

The Steams voyages encourage the development of scientific skills and ocean literacy through the lens of creative tasks at sea. These activities are led by a scientist-in-residence who provides mentoring and introduces research techniques.

The voyage gives trainees the opportunity to use scientific equipment, ranging from plankton nets and microscopes to cutting-edge technology such as remotely operated vehicles. The Steams activities introduce marine research as a potential career to these young people. One said they wanted to train as a marine engineer at nautical college following the voyage.

Ocean experiences provide a foundation for ocean connection. Trainees experience the ocean in sunshine and in gales, day and night, rolling with the waves and observing marine life in its natural environment.

Citizen science projects such as wildlife surveys and recorded beach cleans also develop their ocean stewardship knowledge and skills. One trainee explained how they have "become more interested [in] our marine life and creative ways to help protect it".

Over the next 12 months, the information we collect from the voyages will help us to better understand the benefits and contribute to an important marine social science data gap in young people. It is important to understand how to develop young people's relationships with the ocean, and the knowledge and skills that will empower the next generation of marine citizens.

As one trainee put it: "Being out on the Pelican showed me how vast and powerful the sea is - and how important it is to respect and care for it."

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Pamela Buchan received funding from Economic and Social Research Council for the research cited in this article. The sail training evaluation project received funding from Sail Training International. We would like to thank Charlotte Braungardt for her contribution to this project.

Alun Morgan is affiliated with the Pelican of London as an Ambassador for the organisation

Swedish homes are among the warmest in Europe, reflecting high levels of insulation and longstanding strategies that have kept heating costs low for most households. Antony McAulay/Shutterstock

Swedish homes are among the warmest in Europe, reflecting high levels of insulation and longstanding strategies that have kept heating costs low for most households. Antony McAulay/ShutterstockThe new year in Sweden began with some record-breaking cold temperatures. Temperatures in the village of Kvikkjokk in the northern Swedish part of Lapland dropped to -43.6°C, the lowest recorded since records began in 1887.

Yet for the majority of Swedish households, heating is not an issue. Those living in the multi-household apartment blocks that characterise Sweden's towns and cities enjoy average temperatures of 22°C inside their homes, thanks to communal heating systems that keep room temperatures high and costs low. For many households, heating is charged at a flat rate and included in the rent they pay.

*Some interviewees in this article are anonymised according to the terms of the research.

In the UK, meanwhile, home temperatures average just 16.6 degrees, the lowest in all of Europe. At least 6 million UK households fear the onset of cold weather because they are living in fuel poverty - unable to afford to heat their home to a safe and comfortable level.

The problem is exacerbated by the UK's reliance on natural gas to heat its homes - a fuel which suffers from escalating price volatility. They are also the most poorly insulated in Europe, making them difficult to keep warm.

In Britain, home heating isn't just a political hot potato; it has been shown to cost lives. In the winter of 2022-23, 4,950 people were estimated to have died earlier than expected (known as "excess winter deaths") because of the health effects of living in cold homes - including lung and heart problems as well as damage to mental health. In contrast, despite having a much colder winter climate, Sweden's excess winter deaths index was around 12%, one of the lowest rates in Europe and considerably below the UK's 18% figure.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

So how did two countries that are geographically quite close end up so far apart when it comes to home heating outcomes? As two professors of energy studies - one British, the other Swedish - we have long puzzled over the stark contrast in how winter is experienced inside our homes in the north of England (Sheffield) and southern Sweden (Lund).

For the last three years, we have been researching the modern histories of home heating in both countries (plus Finland and Romania), gathering nearly 300 oral accounts of people's memories of the daily struggle to keep warm at home for long periods each year.

By charting these experiences of home heating in both countries since the end of the second world war, we show how Britain now finds itself struggling to keep its citizens warm in winter while also facing an uphill battle to meet its environmental targets. The stories from Sweden, on the whole, suggest how different things could have been.

Post-war memoriesThe second world war changed many things but not, immediately, the way homes were heated. In the UK coal remained the primary domestic fuel, while Sweden stuck mainly with wood, although coal was becoming more common in cities. Cold homes were still considered normal in both countries, as Majvor* (who is now in her 80s and lives in the Swedish city of Malmö) recalled of her post-war childhood living in a one-room flat:

There was a stove in the room and that was the only source of heat - I have a memory of it being so cold in the winter that my mother had to put all three children in the same bed to keep warm. In the winter, all the water froze to ice, so you had to … heat it on the stove to get hot water.

Despite the cold, many of our interviewees remembered the burning of wood and coal to heat their homes with great affection - although less so the drudgery and dirt that went with it.

"There's just something about a fire, isn't there," Sue (now in her 60s and living in Rotherham, England) told us. "The warmth, the smell, the laughter. It's that family memory and it was just wonderful. Anyone 'round here will tell you the same: life was hard but it was wonderful. We felt loved."

Mary (now in her 70s and also living in Rotherham) is among a very small minority who still heat their home using a coal fire. Her reflections were less positive:

I remember going to fetch coal when I was pregnant. I gave birth two days later … It's the dirt that gets you down, the dirt from the fire. It's disheartening when your walls are always dirty. That's why I had them tiled because I was painting them every six months before that.

Carolina* (now in her mid-30s and living in Malmö) also had a negative recollection of her wood-burning childhood - but for a very different reason. She described how her mother had once "got the axe in her foot … She continued to chop wood anyway - but I kind of got PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] from her doing that. So I can't do it, I'm really scared of it."

In Sweden, home heating was seen as key to improving social conditions after the war. The emphasis was on good-quality homes for everyone as the social welfare concept of folkhem ("the people's home") finally gained traction. The idea had first been articulated by future prime minister Per Albin Hansson in a speech to the Swedish parliament back in 1928, as a way of expressing his vision for a fair and equal society.

From 1946, housing construction was regarded as a key political issue for improving public health and achieving Sweden's other social welfare goals. In several cities, municipally owned public housing companies played an important role in the initial phase of new district heating systems, in part by guaranteeing a secure market. The introduction of the varmhyra ("warm rent") policy meant heating and sometimes other utilities were included in the rent - an arrangement that continues to this day in many Swedish apartment blocks.

The UK, like Sweden, suffered the blight of cold homes during the 1940s, exacerbated by fuel rationing that extended long beyond the war. So it is difficult to explain why Britain's new post-war welfare state did not explicitly address home heating.

Instead, the focus was on public health, with the birth of the National Health Service and recognition that the mass burning of coal was leading to fatal air pollution and unhealthy homes. Heavy city smogs, triggered by widespread coal burning in homes and factories, became increasingly common. The problem reached a climax when the "great smog of 1952" killed approximately 12,000 people, primarily in London, over just five days.

The justification for rapidly phasing out coal as the UK's primary fuel for homes and industry was centred around ending the public health crisis of these killer smogs, rather than on changing the way homes were heated - leading to the introduction of the Clean Air Act (1956). And as the UK scrabbled for a cleaner form of heating, a game-changing discovery was made. Huge reserves of "natural gas" (methane) were found off the Yorkshire coast in 1965, offering the huge advantage of reducing visible air pollutants compared with coal.

One man in particular, Kenneth Hutchison, saw and seized the opportunity to present natural gas as the panacea the UK had been waiting for. As incoming president of the National Society for Clean Air, Hutchison hailed the gas industry as the driving force in Britain's "smokeless revolution". From the late 1960s, he drove the rollout of networks piping natural gas into UK households at an incredible rate, demanding: "We must convince the public that central heating by gas is best" over the grime and drudgery of coal fires.

A 1965 advert for 'high-speed' British gas. Video: Anachronistic Anarchist.The chairman of British Gas, Denis Rooke - not an objective witness, admittedly - described the rollout as "perhaps the greatest peacetime operation in the nation's history". Between 1968 and 1976, around 13 million UK homes (of a total of about 15 million) were made ready for connection to the gas network. The cost of converting domestic heating and cooking systems from coal to gas was largely borne by the national gas supplier, making it effectively free to most households.

Our research suggests this transition was presented to UK households as a fait accompli. But most of our UK-based interviewees remembered the advent of natural gas as a major step forward in cleanliness, comfort and convenience. As 75-year-old Rita from Rotherham recalled of moving into a new council estate with gas heating in 1967:

It was like another universe! It was comfortable, everything became less intense - you didn't need so much clothing … The days of cooking on the fire were gone. Fabulous! The boiler didn't have to go all the time - the gas fire could take the chill off.

Britain's gas rollout not only brought gas central heating but other appliances such as gas fridges and fires that further lightened the domestic load. For Rita's and many other families, it felt like a cascade of liberations which made homes brighter and more enjoyable to live in.

Yet half a century later, Hutchison's faith in gas appears less justified. While it certainly cleaned up the UK's visible air pollution, natural gas is methane by another name - a powerful greenhouse gas.

How Sweden 'futureproofed'With a much smaller population and less crowded cities, air quality in Sweden had been less of a concern than in the UK in the immediate post-war period. But in the 1960s, proposals for a mass home-building programme raised fears this could worsen air pollution.

Without the option of "clean" natural gas, Sweden turned to district heating - an idea which had originated in New York in the 19th century. But Sweden committed to it in a big way during the 1960s and '70s, deciding it was the best way to meet the heating needs of the 1 million homes now being built. This decision shaped the way homes in Sweden are heated: today, some 90% of its multi-family apartment blocks are connected to district heating systems - with heat distributed from power plants (usually on the edge of cities) as hot water via a network of pipes.

Upon its introduction, district heating was celebrated for its efficiency, affordability for households (especially when combined with the warm rent policy), and flexibility - it is easy to change the fuel source. For some municipalities, district heating plants opened up opportunities to produce cheap electricity. Whereas UK households were (and remain) largely individually responsible for paying for their heating, in Sweden it was seen as a collective good.

Even the 1973 oil crisis - when geopolitical tensions in the Middle East quadrupled the price of oil - failed to dent public trust in the Swedish approach to home heating. In response to the oil crisis, Sweden moved quickly to change the fuels used to power district heating, introducing more domestic waste and biomass into the mix - a move that, from a climate perspective, now appears a highly prescient shift.

According to Kjell* (now in his 60s, living in a small town in south-west Sweden), 1973 was "when the whole concept changed because suddenly fossil fuels became expensive". He explained:

The expansion of nuclear power [meant] electricity became very cheap … The government promoted the idea that 'now we should use electricity, we should use direct electric heating' … All you had to do was turn a thermostat, press a button, and it was warm.

As well as nuclear power expansion, Sweden doubled down on hydropower production and was among the earliest European countries to invest in other renewable energy sources. Its government was also an early proponent of the now-familiar concept of energy efficiency - encouraging both households and industry to conserve energy and invest in insulation. By the mid-1990s, every Swedish home was rated by the EU as having comprehensive insulation and double glazing as a minimum. The equivalent figure in the UK in 2025 was only around 50%.

The flagship initiative "Seal up Sweden" encouraged households to insulate homes and restrict room temperature to 20 degrees (still almost four degrees warmer than the average UK home today). And the warm rent system gave landlords a vested interest in improving the energy performance of their properties.

Whether it was realised at the time or not, in the defining moment of the oil crisis, Sweden was futureproofing its urban heating systems - and laying the foundations for its enduring reputation as a leader in clean energy and climate policy. Sweden eschewed energy imports in favour of harnessing its own energy assets through expansion in hydropower, waste and nuclear energy - although this latter commitment would soon be tested by the major 1979 accident at Pennsylvania's Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the US.

The era of power cutsIn stark contrast, the UK's rapid natural gas rollout couldn't move fast enough to protect households from the twin effects of the oil crisis and miners' strikes in the 1970s. Electricity - mostly still generated by coal and oil - was rationed via rolling blackouts. Many workplaces were required to restrict their operations to a three-day week.

With the average British home heated to 13.7 °C at this time (compared with 20-21 °C in Sweden), there was little scope to ask households to cut back further, so nationwide power cuts were imposed instead. Homes were regularly plunged into darkness. Tony (now in his early 70s, from the English town of Whiston on Merseyside) worked as a social worker during this period. He recalled seeing many interiors without doors or bannisters - they had been burnt to keep the family warm.

Extra candles were imported into Britain in 1972 to cope with power cuts. Video: AP Archive.Nonetheless, "clean" gas pioneer Hutchison was feeling vindicated as the UK enjoyed an era of falling gas prices throughout the 1980s. Climate change was still, at most, a nascent agenda, so it didn't seem to matter that British households were living in some of the least energy-efficient (and worst insulated) homes in Europe.

Gas remained affordable through the miners' strike of 1984-85 and privatisation of the gas industry in 1986, with the average household gas bill six times cheaper in real terms than today. Yet British households continued to modestly heat their homes, with average internal home temperatures slowly rising from 16.1 °C in 1990 to 17.8 °C by 1999.

Over the same period, Sweden went through several momentous changes as concern for the environment grew - amid recognition of the greenhouse effect (the build-up of gases trapping heat in the Earth's atmosphere) and acid rain (rainfall made acidic by air pollution). This resulted in another pioneering move: the world's first carbon tax on fossil fuels in 1991, which further galvanised its move away from oil.

Amid Sweden's dash for energy independence, electric-powered home heat pumps increasingly came to be viewed as something of a status symbol. Even households living in multi-family urban apartments were growing increasingly concerned about the monopolistic nature of district heating. They started opting out in favour of individual heat pumps, undermining these collective systems that rely on everyone contributing.

Short-lived progress in the UKBritain was much slower to embrace the need to address the world's climate crisis. One promising intervention finally came in 2006, when Tony Blair's New Labour government required all newly built homes to meet stringent environmental design standards (although this did little to lessen the environmental burden of existing homes).

In turn, higher standards of environmental design in new homes helped establish a market for more environmentally friendly, electric-powered heat pumps in Britain. Installations accelerated from 2004, mainly in social housing. The following year, gas connections peaked at 95% of UK households - then slowly started to fall, down to the current level of 74% across England and Wales.

With this reduction of reliance on gas, the level of emissions associated with heating UK homes also began to decline. Those urging Britain to do something about its position as one of Europe's least environmentally conscious nations celebrated, if cautiously. But this progress, such as it was, proved short-lived.

From 2010, the new Conservative-Lib Dem coalition government began dismantling key initiatives aimed at domestic energy efficiency, including New Labour's Code for Sustainable Homes as well as financial incentives to install heat pumps and renewables such as solar panels. Sales of these technologies started to fall away.

Since then, initiatives to promote adoption of renewable forms of home heating in the UK have been dogged by controversies - such as the renewable heat incentive in Northern Ireland, which resulted in the suspension of senior government officials.

Heat pump technology explained. Video: Nesta.Ambitious plans (driven by the UK's legally binding emissions reduction targets) to install 600,000 heat pumps a year have been met with public suspicion. Uptake is currently at around 50,000 per year - far below the government target.

Since coming to power, the current Labour government has rolled back its manifesto pledge to ban the sale of gas boilers in homes by 2035 - to the consternation of many environmental pressure groups and climate scientists. And while its recent announcement of more comprehensive investment in domestic energy efficiency (as part of the Warm Homes Plan) is a step in the right direction, many experts still consider the level of investment inadequate to secure the scale of change required to meet the UK's net zero climate targets.

A sizable majority (74%) of UK homes are still heated by gas boilers - which emit around twice as much CO₂ each year as some electric-powered heat pumps.

The clean heating conundrumThe volatile political scene in the UK is hampering its transition to clean energy. Reform UK, which has adopted a strident anti-net zero position, has made strong gains with disenfranchised voters, according to numerous polls. Should it gain power at the next general election in 2028 (even if as part of a coalition), Reform is likely to double-down on fossil fuel extraction and use, dealing a severe blow to efforts to wean the UK off its enduring gas dependency.

However, a shift to electric heating would not be an overnight panacea to the UK's energy bill woes. Depending on the energy efficiency of the homes in which they are installed, heat pumps could push bills up in the short-to-medium term, because electricity remains up to five times more expensive than gas.