Attend live on Tue, May 5, 02026 at 7:00PM PT

Tickets on sale soon

Bayo Akomolafe (Ph.D.) is a philosopher, writer, activist, professor of psychology, and executive director of The Emergence Network. Rooted with the Yoruba people, Akomolafe is the father to Alethea and Kyah, and the grateful life-partner to ‘EJ’. Essayist, poet, and author of two books, These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home (North Atlantic Books) and We Will Tell our Own Story: The Lions of Africa Speak, Bayo Akomolafe is also the host of the online postactivist course, ‘We Will Dance with Mountains’. He currently lectures at Pacifica Graduate Institute, California and University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont as adjunct and associate professor, respectively. He sits on the Board of many organizations, including Science and Non-Duality and Local Futures. In July 2022, Dr. Akomolafe was appointed the inaugural Global Senior Fellow of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. He has also been appointed Senior Fellow for The New Institute in Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bayo hopes to inspire what he calls a “diffractive network of sharing” and a “politics of surprise” that sees the crises of our times with a posthumanist lens.

Attend live on Tue, Apr 7, 02026 at 7:00PM PT

at The Interval at Long Now

Tickets on sale soon

Katie Paterson (born 1981, Scotland) is widely regarded as one of the leading artists of her generation. Collaborating with scientists and researchers across the world, Paterson’s projects consider our place on Earth in the context of geological time and change. Her artworks make use of sophisticated technologies and specialist expertise to stage intimate, poetic and philosophical engagements between people and their natural environment. Combining a Romantic sensibility with a research-based approach, conceptual rigour and coolly minimalist presentation, her work collapses the distance between the viewer and the most distant edges of time and the cosmos.

Katie Paterson has broadcast the sounds of a melting glacier live, mapped all the dead stars, compiled a slide archive of darkness from the depths of the Universe, created a light bulb to simulate the experience of moonlight, and sent a recast meteorite back into space. Eliciting feelings of humility, wonder and melancholy akin to the experience of the Romantic sublime, Paterson’s work is at once understated in gesture and yet monumental in scope.

Katie Paterson has exhibited internationally, from London to New York, Berlin to Seoul, and her works have been included in major exhibitions including Turner Contemporary, Hayward Gallery, Tate Britain, Kunsthalle Wien, MCA Sydney, Guggenheim Museum, and The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. She was winner of the Visual Arts category of the South Bank Awards, and is an Honorary Fellow of Edinburgh University

Attend live on Wed, Mar 18, 02026 at 7:00PM PT

at Cowell Theater in Fort Mason Center

Tickets on sale soon

Melody Jue is Professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research and writings center the ocean humanities, science fiction, media studies, science & technology studies, and the environmental humanities.

Professor Jue is the author of Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater(Duke University Press, 2020), which won the Speculative Fictions and Cultures of Science Book Prize, and the co-editor of Saturation: An Elemental Politics (Duke University Press, 2021) with Rafico Ruiz. Forthcoming books include Coralations (Minnesota Press, 2025) and the edited collection Informatics of Domination (Duke Press, 2025) with Zach Blas and Jennifer Rhee.

Her new work, Holding Sway, examines the media of seaweeds across transpacific contexts. She regularly collaborates with ocean scientists and artists, from fieldwork to collaborative writings and other projects. Many of her writings are informed by scuba diving fieldwork and coastal observations.

Attend live on Tue, Jan 27, 02026 at 7:00PM PT

at Cowell Theater in Fort Mason Center

Tickets on sale soon

Indy is co-founder of Dark Matter Labs and of the RIBA award winning architecture and urban practice Architecture00. He is also a founding director of Open Systems Lab, seeded WikiHouse (open source housing) and Open Desk (open source furniture company).

Indy is a non-executive international Director of the BloxHub, the Nordic Hub for sustainable urbanization. He is on the advisory board for the Future Observatory and is part of the committee for the London Festival of Architecture. He is also a fellow of the London Interdisciplinary School.

Indy was 2016-17 Graham Willis Visiting Professorship at Sheffield University. He was Studio Master at the Architectural Association - 2019-2020, UNDP Innovation Facility Advisory Board Member 2016-20 and RIBA Trustee 2017-20.

He has taught & lectured at various institutions from the University of Bath, TU-Berlin; University College London, Princeton, Harvard, MIT and New School. He is currently a professor at RMIT University.

He was awarded the London Design Medal for Innovation in 2022 and an MBE for Services to Architecture in 2023.

“One of the peculiar things about the 'Net is it has no memory. (…) We’ve made our digital bet. Civilization now happens digitally. And it has no memory. This is no way to run a civilization. And the Web — its reach is great, but its depth is shallower than any other medium probably we’ve ever lived with.” (Kahle 01998)

In February 01998, the Getty Center in Los Angeles hosted the Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity conference, organized by the founders and thinkers of two non-profit organizations established two years earlier in San Francisco: the Internet Archive and The Long Now Foundation, both dedicated to long-term thinking and archiving.

The Internet Archive has since become a global example of digital archiving and an open library that provides access to millions of digitized pages from the web and paper books on its website. The Long Now Foundation’s central project involves the design and construction of a monumental clock intended to tick for the next 10,000 years, promoting long-term thinking alongside its lesser-known archival mission: the Rosetta Project.

The Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity conference brought together these organizations to discuss what the Internet Archive’s founder, Brewster Kahle, referred to as “our digital bet”: a digital-only novel form of civilization with no history, posing challenges to the preservation of its immaterial cultural memory. Discussions at the conference raised concerns about the longevity of digital formats and explored potential archival and transmission solutions for the future. This foresight considered the ‘heritage’ characteristics of the digital world, which were yet to be defined as such on a global level. It was not until 02003 that UNESCO published a charter advocating for “digital heritage conservation”, distinguishing between “digital-born heritage” and digitized heritage (UNESCO 02003, Musiani et al. 02019). The Getty Center conference thus emerges as a precursor in the quest to preserve both digital data and analog information for future generations. This endeavor, the chapter argues, aligns with the longue durée, a conception of time and history developed by French historian Fernand Braudel during World War Two (Braudel 01958).

While the Internet Archive has envisioned such a mission through the continuous digital recording of web pages and the digitization of paper, sound, and video documents into bits format, The Long Now Foundation’s Rosetta Project began to take shape during the ‘Time and Bits’ conversations, offering a different approach to data conservation in an analog microscopic format, engraved on nickel disks.

Taking the 01998 gathering of the Internet Archive and Long Now Foundation as a starting point, this chapter aims to examine the challenges and strategies of ‘digital continuity management’ (or maintenance). It proposes to analyze the different ways these two case studies envision archiving and transmission to future generations, in both digital and analog formats — bits and nickel, respectively — for virtual web content and physical paper-based materials.

Through a comparative analysis of these two non-profit organizations, this chapter seeks to explore various archiving methods and tools, and the challenges they present in terms of time, space, innovation, maintenance, and ‘continuity’. By depicting two distinct visions of the future of archiving represented by these organizations, it highlights their shared mission of safeguarding, sharing, and providing universal access to information, despite their differing formats.

The method used for this analysis combines theoretical, comparative, and qualitative studies through an immersive research process spanning over three years in the San Francisco Bay Area. This process involved conducting interviews and participant observations during seminars, talks, and meetings held by both The Long Now Foundation and at the Internet Archive. Additionally, archival research was conducted online, using resources such as the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine and The Long Now Foundation’s blog dating back to 01996, as well as on-site at The Long Now Foundation.

This chapter adopts a multidisciplinary approach conjoining history, media, maintenance, and American studies to analyze the challenges faced by these two organizations in transmitting both material and intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO 02003).

The first part of this chapter concentrates on the future of archives and their longevity, a topic that was discussed during the 01998 Time and Bits conference. It suggests a parallel with the Braudelian longue durée perspective, which offers a novel understanding of time and history.

The second part focuses on digital transmission in ‘hard-drive form’ using the example of the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine, comprising thousands of hard drives. The final segment of this chapter discusses the analog archival format chosen by The Long Now Foundation, represented by the Rosetta Disk, a small nickel disk engraved with thousands of pages of selected texts. This format is likened to a modern iteration of the Egyptian Rosetta Stone for preservation into the long-term future.

“Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity”…and maintenance in longue durée“How long can a digital document remain intelligible in an archive?” This question, asked by futurist Jaron Lanier in one of the hundreds of messages posted on the Time and Bits forum that ran from October 01997 until June 01998, underscores not only concerns about the future ‘life’ of digital documents at the end of the 01990s, but also their meaning and understanding in archives for future generations. These concerns about digital preservation were central to discussions at the subsequent Time and Bits conference organized a few months later in February 01998 at the Getty Center in Los Angeles by the Getty Conservation Institute and the now defunct Getty Information Institute, in collaboration with The Long Now Foundation.

The Long Now Foundation, formed in 01996, emerged from discussions among thinkers and futurists who later became its board members. This group included Stewart Brand, recipient of the 01971 National Book Award for his Whole Earth Catalog and co-founder of the pioneering virtual community, the WELL, created in the 01980s (Turner 02006), engineer Danny Hillis, British musician and artist Brian Eno, technologists Esther Dyson and Kevin Kelly, and futurist Peter Schwartz (Momméja 02021). Schwartz, in particular, is the one who articulated the concept of the ‘long now’ as a span of 20,000 years — 10,000 years deep into the past and 10,000 years into the very distant future. This timeframe coincides with the envisioned lifespan of the monumental Clock being constructed by the foundation in West Texas. The choice of this specific duration marks the end of the last ice age about 10,000 years ago, a period that catalyzed the advent of agriculture and human civilization, with some scholars even identifying it as the onset of the Anthropocene epoch. Indeed, a group of scientists extends their analysis beyond the industrial era, which has generally been studied as the beginning of this human-induced transformation of our biosphere, considering the origins of agriculture as “the time when large-scale transformation of land use and human-induced species and ecosystem loss extended the period of warming after the end of the Pleistocene” (Henke and Sims 02020). For the founders of The Long Now Foundation, this 10,000-year perspective must therefore be developed in the opposite direction, towards the future (hence the expected duration of the Clock) forming the ‘Long Now’.

The paper argues that ‘long now’ promoted by the organization can be paralleled with the concept of longue durée put forth by Annales historian Fernand Braudel. Braudel began elaborating the idea of longue durée during his time as prisoner of war in Germany. For five years, he diligently worked on his PhD dissertation, La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II (Braudel 01949). It was during his internment that Braudel developed the concept of the ‘very long time’, a temporal construction that provided him solace from the traumatic events he experienced in the ‘short time’ and helped him gain insight into his condition by situating them on a much broader time scale (Braudel 01958). With newly stratified temporalities ― from the immediate to the medium to the very long term ― Braudel succeeded in escaping the space-time of which he was a prisoner, a ‘here’ and ‘now’ devoid of meaningful perspectives when a longer ‘now’ would liberate him from the present moment. Longue durée was thus imagined as a novel long-term approach to history, diverging from traditional narratives that focused on brief periods and dramatic events, such as wars. This is what Braudel referred to as “a rushed, dramatic narrative” (Braudel 01958). A second, longer type of history, based on economic cycles and conjunctures, was described by Braudel as spanning several decades, while longue durée offered a novel type of history that transcended events and cycles, extending even further to encompass centuries ― although the French historian refrained from specifying an exact timeframe.

Longue durée, alongside its modern Californian counterpart, the ‘long now’, prompts us to reconsider our understanding of history in time as a means to encapsulate events far beyond our lifetimes. Braudel insisted historians should incorporate longue durée into their work and rethink history as an ‘infrastructure’ composed of layers of ‘slow history’.

Given this perspective, how can we archive and transmit fast traditional history within the context of longue durée? In his foreword to the Time & Bits report, Barry Munitz, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, explained the initiative behind the conference:

We take seriously the notion of long-term responsibility in the protection of important cultural information, which in many cases now is recorded only in digital formats. The technology that enables digital conversion and access is a marvel that is evolving at lightning speed. Lagging far behind, however, are the means by which the digital legacy will be preserved over the long term (Munitz 01998).

The two organizations selected for this chapter offer two distinct, yet complementary, visions of how archiving and transmitting should be approached, now and for the longue durée, in digital and analog formats.

Digital transmission in ‘hard-drive form’: The Wayback Machine and the Internet ArchiveAddressing the “problem of our vanishing memory” was a focal point of the Time & Bits conference encapsulated by Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle’s question: “I think the issue that we are grappling with here is now that our cultural artifacts are in digital form, what happens?” (Kahle 01998). As noted by Stewart Brand, Kahle also pointed out that “one of the peculiar things about the 'Net is it has no memory. (…) We’ve made our digital bet. Civilization now happens digitally. And it has no memory. This is no way to run a civilization. And the Web—its reach is great, but its depth is shallower than any other medium probably we’ve ever lived with” (Kahle 01998).

As a way to resolve this ‘digital bet’ and the pressing need for ‘digital continuity’, Brewster Kahle embarked on a mission to archive the web on a massive scale, giving rise to the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine: an archive comprising 20,000 hard drives and containing 866 billion web pages as of March 02024.

Like The Long Now Foundation, the Internet Archive is a non-profit organization founded in 01996 in San Francisco. In fact, both entities once occupied adjacent offices in the Presidio. Their missions can also be put in parallel: whereas The Long Now Foundation promotes long-term thinking through projects like the construction of a Clock and the preservation of foundational languages and texts of our civilization in analog form through the Rosetta Disk, the Internet Archive digitizes and archives analog documents and records digital textual heritage through its Wayback Machine.

The Internet Archive embarked on its mission with an imperative to save internet pages, immaterial data composed of bits, which had not previously been archived: “We began in 01996 by archiving the internet itself, a medium that was just beginning to grow in use. Like newspapers, the content published on the web was ephemeral ― but unlike newspapers, no one was saving it” (Internet Archive 02024). Despite the transient and intangible nature of web pages, the Internet Archive remains committed to this mission, continuing to archive internet pages in a digital format to this day, with the ambition to remain open and collaborative, “explicitly promoting bottom-up initiatives intended to revalue human intervention” (Musiani et al. 02019).

Brewster Kahle, who could be regarded as the first digital librarian in history, promotes “Universal Access to All Knowledge” and “Building Libraries Together”. These missions, as explained during the Internet Archive's annual celebration on October 21, 02015, at its headquarters in San Francisco, highlight the organization’s commitment to a wide array of digital content, including internet pages, books, videos, music, and games. Therefore, the internet appears as a “heritage and museographic object” (Schafer 02012), with information worth saving and protecting for the future. While the Library of Congress recently acknowledged the significance of Twitter content as a form of heritage (Schafer 02012), the Internet Archive has been standing as an advocate for the preservation and transmission of digital heritage as early as the 01990s. UNESCO further validated this recognition in 02003 by acknowledging the existence of “digital heritage as a common heritage” through a charter on the conservation of digital heritage (Musiani et al. 02019) where resources are ‘born digital’, before being, or even without ever being, analog:

Digital materials encompass a vast and growing range of formats, including texts, databases, still and moving images, audio, graphics, software, and web pages. Often ephemeral in nature, they require purposeful production, maintenance, and management to be retained. Many of these resources possess lasting value and significance, constituting a heritage that merits protection and preservation for current and future generations. This ever growing heritage may exist in any language, in any part of the world, and in any area of human knowledge or expression (UNESCO 02003).

The Internet Archive’s mission aligns perfectly with this definition, providing open access to documents that are "protected and preserved for current and future generations”, echoing once again The Long Now Foundation’s own mission. However, the pursuit of "universal access to all knowledge" raises questions about the quality or "representativeness of the archive" (Musiani et al. 02019) in the face of the abundance and diversity of the sources and formats available.

For instance, the music section of the Internet Archive connects visitors to San Francisco’s local counterculture history with a vast collection of recordings from Grateful Dead shows (17,453 items) that fans contributed to the organization in analog formats for digitization. This exchange has not only allowed the band’s fan community to flourish but has also bolstered the group’s the popularity: “they started to record all those concerts and you know, there are I think 2,339 concerts that got played by the Grateful Dead (…) and all but 300 of those are here in the archive” (Barlow 02015). In this way, the Internet Archive confirms its role as a universal collaborative platform and effectively contributes to a “new era of cultural participation” (Severo and Thuillas 02020), one that is proper to Web 2.0 but which the non-profit has been championing since the 01990s.

However, for the Internet Archive, and digital technology in general, to truly guarantee the archiving of human heritage ‘for future generations’ over the years, whether initially analog or digital, it is imperative to continuously improve and update storage formats and units to combat obsolescence and adapt to evolving technologies:

Of course, disk drives all eventually fail. So we have an active team that monitors drive health and replaces drives showing early signs for failure. We replaced 2,453 drives in 02015, and 1,963 year-to-date 02016… an average of 6.7 drives per day. Across all drives in the cluster the average ‘age’ (arithmetic mean of the time in-service) is 779 days. The median age is 730 days, and the most tenured drive in our cluster has been in continuous use for 6.85 years! (Gonzalez 02016)

If “all contributions produced on these platforms, whether amateur or professional, participate in the construction and appropriation of cultural and memorial heritage” (Severo and Thuillas 02020), reliance solely on digital technology poses a substantial challenge to the preservation of our cultures in longue durée. Aware of the inherent risks associated with archiving both analog and ‘digital heritage’ on storage mediums with limited lifespans, the Internet Archive must make the maintenance and replacement of the hard drives that comprise its Wayback Machine a constant priority.

From stone to disk: the Rosetta Project through time and spaceTo embody Braudel’s notion of ‘slow history’ and foster long-term thinking among people, The Long Now Foundation envisioned not only a monumental Clock as a time relay for future generations, but also a library for the deep future, soon materializing as an engraved artifact: The Rosetta Disk.

As explained by technologist Kevin Kelly, the concept of a miniature storage system comprising 350,000 pages of text engraved on a nickel disk, measuring just under eight centimeters in diameter, was proposed by Kahle during the Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity conference, “as a solution for long-term digital storage (…) with an estimated lifespan of 2,000–10,000 years” (Kelly 02008). These meeting discussions thus led to the emergence of the Rosetta Project within The Long Now Foundation, drawing inspiration from the Rosetta Stone. The final version of the Rosetta Project’s Disk was unveiled in 02008: 14,000 pages of information in 1,500 different languages (Welcher 02008). Crafted in analog format, it was conceived as the solution to the ever-changing landscape of digital technologies.

While the Internet Archive possesses infinite possibilities for archiving, The Long Now Foundation’s analog choice demands a thoughtful selection of texts to be micro-engraved onto the disk. The foundation decided to focus on several texts, both symbolic and universalist, such as the 01948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, along with Genesis, chosen for its numerous translations. Materials with a linguistic or grammatical vocation, such as the Swadesh list — a compendium of words establishing a basic lexicon for each language — were included, as well as grammatical information including descriptions of phonetics, word formation, and broader linguistic structures like sentences.

Unlike Kahle's digital and digitized heritage project, the Foundation’s language archive is exclusively engraved, accessible only through a microscope. Such an archive is thus a finite heritage, with no scope for future development beyond the creation of new disks displaying new texts. While the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine are constantly evolving, updated through constant digitization and the preservation of new web pages, the format and size of the nickel disk remain immutable.

To ensure the long-term survival of this archive, the foundation has embraced the “LOCKSS” principle — Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe — and has opted to duplicate its Rosetta Disk. By distributing these duplicates worldwide, the project stands a greater chance of lasting in longue durée: “this project in long-term thinking would do two things: it would showcase this new long-term storage technology, and it would give the world a minimal backup of human languages” (Kelly 02008).

The final version of the Rosetta Disk, containing 14,000 micro-engraved pages, was presented at the Foundation's headquarters in 02008. “Kept in its protective sphere to avoid scratches, it could easily last and be read 2,000 years into the future” (Welcher 02008). Beyond its resilience within the timeline of the Long Now, the analog Rosetta Disk aspires to endure across space as well. Remarkably, as the Foundation had been developing its project since 01999, they were contacted by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Rosetta Mission team which, coincidentally, was working on the launch of an exploratory space probe aptly named Rosetta. The Rosetta probe was launched on March 2, 02004, aboard an Ariane 5G+ rocket from Kourou, with the mission of studying comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (‘Tchouri’) located near Jupiter. On board the probe was the very first version of the Rosetta Disk, less comprehensive than the version unveiled in 02008, nevertheless containing six thousand pages of translated texts.

ConclusionOn November 12, 02014, over a decade after its departure from Earth, the Rosetta probe finally reached Comet Tchouri. Upon arrival, it deployed its Philae lander onto the comet’s surface, where, despite unexpected rebounds, it eventually stabilized itself to conduct programmed analyses. Nearly two years later, on September 30, 02016, the Rosetta module, with the Rosetta Disk on board, joined Philae on Tchouri, thus marking the conclusion of the mission: “With Rosetta we are opening a door to the origin of planet Earth and fostering a better understanding of our future. ESA and its Rosetta mission partners have achieved something extraordinary today” (ESA 02014). Through a space mission focused on the future with the aim of better understanding the Earth's past, the Rosetta Disk fulfilled its project to become an archive in longue durée, transcending temporal and spatial boundaries.

Almost ten years later, both the Rosetta Disk and the Internet Archive, through a selection of books and documents from its datasets, became part of an even larger spatial archive which also includes articles from Wikipedia and books from Project Gutenberg, all etched on thin sheets of nickel. The Arch Mission Foundation’s Lunar Library successfully landed on the Moon on February 22, 02024, thus reuniting for the first time the two non-profits’ archival materials in a cultural and civilizational preservation project, built to remain on the Moon surface throughout the longue durée.

The Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity conference did not present a single solution to the challenges of digital archives and data transmission. Instead, it offered a range of options and tools for web archives, digital data, and analog documents to address our ‘digital bet’. The two cases presented appear as two faces of the same disk — digital and analog — with a shared conservation objective: providing different means to consider longue durée and ensure archival continuity and maintenance in the long term. This continuity extends not only through time, but also across space, placing “digitally-born heritage” (Musiani et al. 02019) and more traditional forms of heritage on equal footing.

From the “creative city” (Florida 02002) of San Francisco, both organizations have managed to extend the boundaries of the “creative Frontier” (Momméja 02001), not only physically and digitally, but also through longue durée and space. From hard drives to disks, they offer a new form of coevolution between humans and machines, a ‘post-coevolution’ aimed at transmitting our cultural heritage to future generations through bits and nickel.

ReferencesBrand, Stewart. 01999. The Clock of The Long Now: Time and Responsibility. New York: BasicBooks.

The European Space Agency. 02002. “Rosetta Disk Goes Back to the Future.” The European Space Agency. December 3.

https://web.archive.org/web/20240423005130/https://sci.esa.int/web/rosetta/-/31242-rosetta-disk-goes-back-to-the-future.

———. n.d. “Enabling & Support – Rosetta.” The European Space Agency. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423005544/https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Operations/Rosetta.

———. n.d. “Rosetta – Summary.” The European Space Agency. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423004357/https://sci.esa.int/web/rosetta/2279-summary.

———. n.d. “Where Is Rosetta?” The European Space Agency. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423003218/https://sci.esa.int/where_is_rosetta/.

Florida, Richard. 02002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gonzalez, John. 02016. “20,000 Hard Drives on a Mission.” Internet Archive Blogs. October 25. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423002926/https://blog.archive.org/2016/10/25/20000-hard-drives-on-a-mission/.

Henke, Christopher R, and Benjamin Sims. 02020. Repairing Infrastructures the Maintenance of Materiality and Power. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423002248/https://direct.mit.edu/books/oamonograph/4962/Repairing-InfrastructuresThe-Maintenance-of.

Internet Archive. 02015. “Building Libraries Together, Celebrating the Passionate People Building the Internet Archive.” Internet Archive, San Francisco, October 21. https://archive.org/details/buildinglibrariestogether2015.

Internet Archive. 02024. “About the Internet Archive.” Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423001744/https://archive.org/about/.

Kahle, Brewster. 02011. “Universal Access to All Knowledge.” San Francisco, November 30. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423001555/https://longnow.org/seminars/02011/nov/30/universal-access-all-knowledge/.

Kahle, Brewster. 02016. “Library of the Future.” University of California Berkeley, Morrison Library, March 3. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423001315/https://bcnm.berkeley.edu/events/109/special-events/1004/library-of-the-future.

Kelly, Kevin, Alexander Rose, and Laura Welcher. “Disk Essays.” The Rosetta Project. https://web.archive.org/web/20240422235700/https://rosettaproject.org/disk/essays/.

Kelly, Kevin. 02008. “Very Long-Term Backup.” The Long Now Foundation. August 20. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423000131/https://longnow.org/ideas/very-long term-backup/.

The Long Now Foundation. “Time and Bits: Managing Digital Continuity.” 01998. February 8.https://web.archive.org/web/20240423001231/https://longnow.org/events/01998/feb/08/time-and-bits/.

MacLean, Margaret G. H., Ben H. Davis, Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Information Institute, and Long Now Foundation, eds. 01998. “Time & Bits: Managing Digital Continuity.” [Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust].

Momméja, Julie. 02021. “Du Whole Earth Catalog à la Long Now Foundation dans la Baie de San Francisco : Co-Évolution sur la “Frontière” Créative (1955–2020).” Paris: Paris 3 – Sorbonne Nouvelle. https://theses.fr/2021PA030027.

Musiani, Francesca, Camille Paloque-Bergès, Valérie Schafer, and Benjamin Thierry. 02019. “Qu’est-ce qu’une archive du Web?” https://books.openedition.org/oep/8713/.

The Rosetta Project. n.d. “Disk – Concept.” The Rosetta Project. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423002348/https://rosettaproject.org/disk/concept/.

———. n.d. “The Rosetta Blog.” The Rosetta Project. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423002731/https://rosettaproject.org/blog/.

———. n.d. “The Rosetta Project, A Long Now Foundation Library of Human Language.” The Rosetta Project. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423003014/https://rosettaproject.org/.

Schafer, Valérie. 02012. “Internet, Un Objet Patrimonial et Muséographique.” Colloque Projet pour un musée informatique et de la société numérique, Musée des arts et métiers, Paris. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423012521/http://minf.cnam.fr/PapiersVerifies/7.3_internet_objet_patrimonial_Schafer.pdf.

Severo, Marta, and Olivier Thuillas. 02020. “Plates-formes collaboratives : la nouvelle ère de la participation culturelle ?” Nectart 11 (2). Toulouse: Éditions de l’Attribut: 120– 31. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423003238/https://www.cairn.info/revue-nectart 2020-2-page-120.htm.

Turner, Fred. 02006. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

UNESCO. 02004. “Records of the General Conference, 32nd Session, Paris, 29 September to 17 October 02003, v. 1: Resolutions.” UNESCO. General Conference, 32nd,0 2003 [36221]. https://web.archive.org/web/20240423004242/https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf 0000133171.page=81.

_

"Time, bits, and nickel: Managing digital and analog continuity" was originally published in Exploring the Archived Web during a Highly Transformative Age: Proceedings of the 5th international RESAW conference, Marseille, June 02023 (Ed. by Sophie Gebeil & Jean-Christophe Peyssard.) Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

When I became the father of twin boys, I found myself suspended in a new kind of time — time measured not in days or deadlines, but in lifetimes.

Drifting in a sea of dreams about what their futures might hold, I began to wonder:

If I was dreaming dreams on their behalf, then what dreams had I inherited from my parents, and which were truly my own?

In that moment, I ceased to see myself as a captain of my family’s future and began to feel more like a confluence of currents, with dreams flowing through me.

I was no longer just having dreams — some of my dreams, I imagined, were having me.

Growing up, I absorbed certain dreams through osmosis: my father's admiration for public service, my mother's love of beauty, my country's dream of freedom.

Who would I be if not for this inheritance of dreams?

Who would anyone be if not for theirs?

Perhaps the better question is this:

What do we do with the dreams we receive?

Each generation must wrestle with the dreams they inherit: some are carried forward, consciously or not, and others are released or transformed.

That was always hard enough. Today, we must also grapple with the dreams that are increasingly suggested to us by invisible algorithms.

AI systems may not dream as we do, but they are trained on the archives of human culture.

Just as a parent’s unspoken dream can shape a child’s path, a machine’s projections can influence what we see as possible, desirable, or real.

As machines begin to dream alongside us, perhaps even for us, questioning where our dreams come from and remembering how to dream freely has never been more important.

Dreaming FreelyOne of the most iconic episodes of dreaming freely took place just blocks from where I live.

In the summer of 1967, thousands of young people converged on San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, rejecting the societal norms of their day for dreams of peace, freedom, and self-expression.

Some of those dreams were lost to excess, while others were co-opted by spectacle, or overcome by the weight of their own idealism. Yet many planted seeds that grew deep roots over the ensuing decades.

Several of those seeds drifted south, to the orchards and garages of what became Silicon Valley, where software engineers turned ideals from the counterculture into technology products.

Dreams of expanded consciousness shaped the market for personal computing.

Dreams of community became the power of networks.

The Whole Earth Catalog's "access to tools" became Apple's "tools for the mind.”

Today, many of those tools nudge us toward the embrace of dreams that feel genuine but are often in fact projected onto us.

As we embrace technologies born of generations that once dared to dream new dreams, we find ourselves ever more deeply enmeshed in the ancient process of intergenerational dream transmission, now amplified by machines that never sleep.

Embodied ArchivesThe transmission of dreams across generations has always been both biological and cultural.

Our dreams are shaped not just by the expectations we inherit or reject, but by the bodies that carry them.

This is because our genes carry the imprint of ancestral experience, encoding survival strategies and emotional tendencies. Traits shaped by stress or trauma ripple across generations, influencing patterns of perception, fear, ambition, and resilience.

Inherited dreams contain important information and are among the deep currents of longing that give life meaning: dreams of justice passed down by activists, dreams of wholeness passed down by survivors, dreams of belonging shared by exiles.

They can be gifts that point us toward better futures.

Like biological complexity, these dream currents layer and accumulate over generations, forming an inheritance of imagination as real as the color of our eyes. They echo outward into the stories we collect, the institutions we build, and into the AI models we now consult to make sense of the world.

What begins as cellular memory becomes cultural memory, and then machine memory, moving from body to society to cloud, and then back again into mind and body.

There’s plenty of excitement to be had in imagining how AI may one day help us unlock dormant aspects of the mind, opening portals to new forms of creativity.

But if we sever our connection to the embodied archives of our elders or the actual archives that contain their stories, we risk letting machines dream for us — and becoming consumers of consciousness rather than its conduits and creators.

Temples of ThoughtLibraries are among our most vital connections to those archives.

For thousands of years, they have served as temples of knowledge, places where one generation's dreams are preserved for the next. They have always been imperfect, amplifying certain voices while overlooking others, but they remain among our most precious public goods, rich soil from which new dreams reliably grow.

Today, many of these temples are being dismantled or transformed into digital goods. As public libraries face budget cuts, and book readership declines, archive materials once freely available are licensed to AI companies as training data.

AI can make the contents of libraries more accessible than ever, and help us to magnify and make connections among what we discover. But it cannot yet replace the experience of being in a library: the quiet invitation to wander, to stumble upon the unexpected, to sit beside a stranger, to be changed by something you didn’t know you were looking for.

As AI becomes a new kind of archive, we need libraries more than ever — not as nostalgic relics, but as stewards of old dreams and shapers of new ones.

Just down the street, a new nonprofit Counterculture Museum has opened in Haight-Ashbury.

It preserves the dreams that once lived in bodies now gone or fading.

Those dreams live on in the museum’s archives.

They also live on in algorithms, where counterculture ideals have been translated into code that increasingly shapes how we dream.

Digital DreamsArtificial intelligence models are now among the largest repositories of inherited knowledge in human history. They are dream keepers, and dream creators.

They absorb the written, spoken, and visual traces of countless lives, along with the biases of their designers, generating responses that mirror our collective memory and unresolved tensions.

Just as families convey implicit values, AI inherits not just our stated aspirations, but the invisible weight of what we've left unsaid. The recursive risk isn't merely that AI feeds us what we want to hear, but that it withholds what we don't, keeping us unaware of powerful forces that quietly and persistently shape our dreams.

Philip K. Dick’s 01968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? imagined a future San Francisco (roughly our present day, five decades after the Summer of Love) in which the city is overrun with machines yearning to simulate emotions they cannot feel.

His question — whether machines can dream as we do — is no longer sci-fi. Now we might reasonably ask: will future humans be able to dream without machines?

In some ways, AI will expand our imaginative capacities, turning vague hopes into vivid prototypes and private musings into global movements.

This could ignite cultural revolutions far more sweeping than the Summer of Love, with billions of dreams amplified by AI.

Amidst such change, we should not lose touch with our innate capacity to dream our own dreams.

To dream freely, we must sometimes step away – from the loops of language, the glow of screens, the recursive churn of inherited ideas – and seek out dreams that arise not from machines or archives, but from the world itself.

Dreaming with NatureDreams that arise from nature rarely conform to language.

They remind us that not all meaning is created by humans or machines.

"Our truest life is when we are in dreams awake," wrote Thoreau, reflecting on how trees, ponds, and stars could unlock visions of a deeper, interconnected self.

This wisdom, core to America's Transcendentalist Movement, drew from many sources, including Native Americans who long sought dreams through solitude in the wild, recognizing nature not as backdrop but as teacher.

They turned to wild places for revelation, to awaken to dreams not of human making, but of the earth's.

When we sit quietly in a forest or look up at the night sky, we begin to dream on a different wavelength: not dreams of achievement or optimization, but dreams of connection to something much deeper.

In nature, we encounter dreams that arise from wind and stone, water and root, birdsong and bark.

They arrive when we contemplate our place in the wider web of existence.

Dreaming AnewAt night, after reading to my boys and putting them to bed, I watch them dreaming.

I try not to see them as vessels for my dreams, but as creators of their own.

When they learn to walk, I’ll take them outside, away from digital screens and human expectations, to dream with nature, as humans always have, and still can.

Then I’ll take them to libraries and museums and family gatherings, where they can engage with the inheritance of dreams that came before them.

When they ask me where dreams come from, I’ll tell them to study the confluence of currents in their lives, and ask what’s missing.

What comes next may be a dream of their own.

At least, that is a dream that I have for them.

The Inheritance of Dreams is published with our friends at Hurry Up, We're Dreaming. You can also read the essay here.

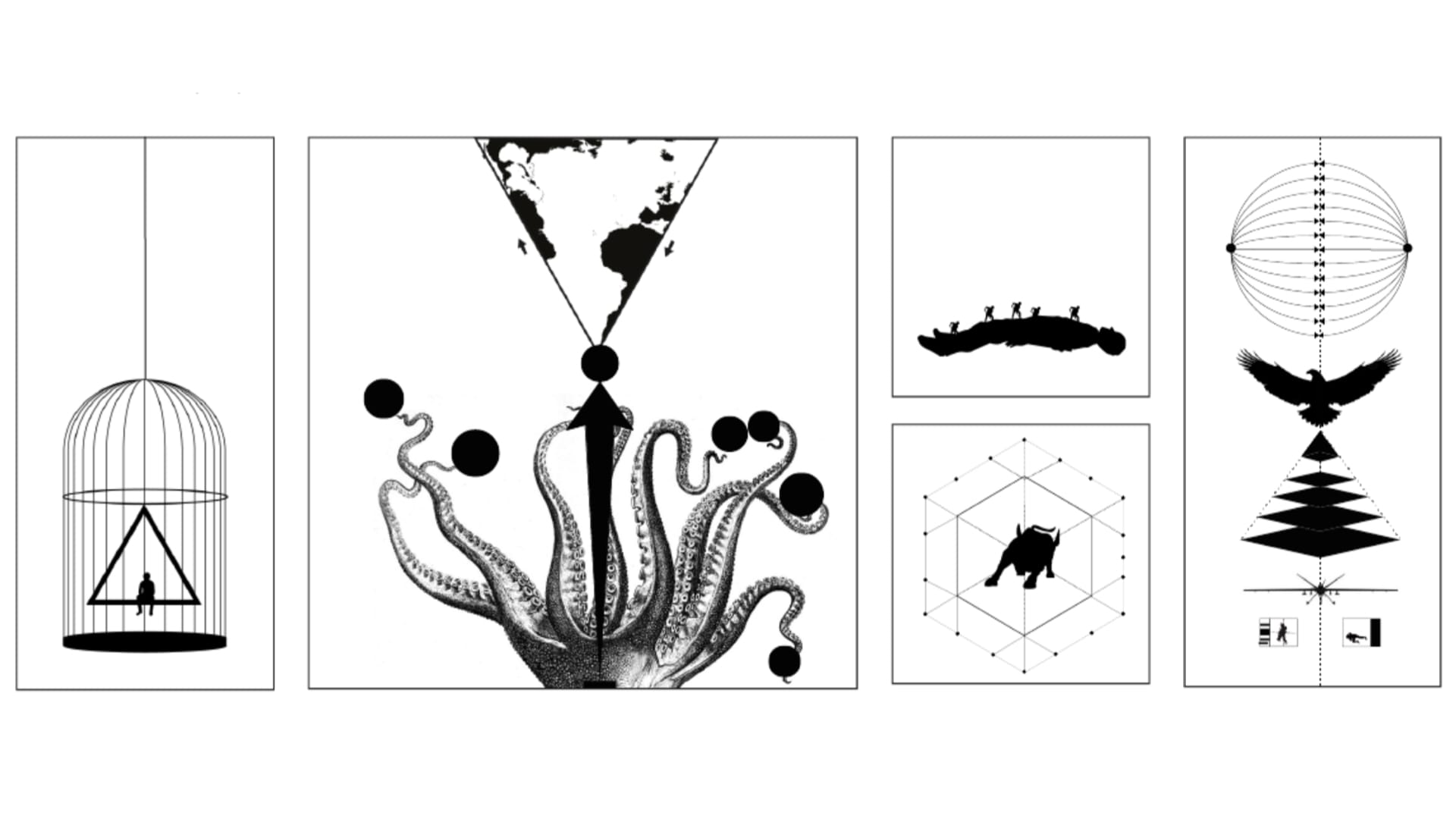

Our immediate history is steeped in profound technological acceleration. We are using artificial intelligence to draft our prose, articulate our vision, propose designs, and compose symphonies. Large language models have become part of our workflow in school and business: curating, calculating, and creating. They are embedded in how we organize knowledge and interpret reality.

I’ve always considered myself lucky that my journey into AI began with social impact. In 02014, I was asked to join the leadership of IBM’s Watson Education. Our challenge was to create an AI companion for teachers in underserved and impacted schools that aggregated data about each student and suggested personalized learning content tailored to their needs. The experience showed me that AI could do more than increase efficiency or automate what many of us consider to be broken processes; it could also address some of our most pressing questions and community issues.

It would take a personal encounter with AI, however, for me to truly grasp the technology’s potential. Late one night, I was working on a blog post and having a hard time getting started — the blank page echoing my paralysis. I asked Kim-GPT, an AI tool I created and trained on my writing, to draft something that was charged with emotion and vulnerability. What Kim-GPT returned wasn’t accurate or even particularly insightful, but it surfaced something I had not yet admitted to myself. Not because the machine knew, but because it forced me to recognize that only I did. The GPT could only average others’ insights on the subject. It could not draw lines between my emotions, my past experiences and my desires for the future. It could only reflect what had already been done and said.

That moment cracked something open. It was both provocative and spiritual — a quiet realization with profound consequences. My relationship with intelligence began to shift. I wasn’t merely using the tool; I was being confronted by it. What emerged from that encounter was curiosity. We were engaged not in competition but in collaboration. AI could not tell me who I was; it could only prompt me to remember. Since then, I have become focused on one central, persistent question:

What if AI isn’t here as a replacement or overlord, but to remind us of who we are and what is possible?AI as Catalyst, Not Threat

We tend to speak about AI in utopian or dystopian terms, but most humans live somewhere in between, balancing awe with unease. AI is a disruptor of the human condition — and a pervasive one, at that. Across sectors, industries and nearly every aspect of human life, AI challenges long-held assumptions about what it means to think, create, contribute. But what if it also serves as a mirror?

In late 02023, I took my son, then a college senior at UC-Berkeley and the only mixed-race pure Mathematics major in the department, to Afrotech, a conference for technologists of color. In order to register for the conference he needed a professional headshot. Given the short notice, I recommended he use an AI tool to generate a professional headshot from a selfie. The first result straightened his hair. When he prompted the AI again, specifying that he was mixed race, the resulting image darkened his skin to the point he was unrecognizable, and showed him in a non-professional light.

AI reflects the data we feed it, the values we encode into it, and the desires we project onto it. It can amplify our best instincts, like creativity and collaboration, or our most dangerous biases, like prejudice and inequality. It can be weaponized, commodified, celebrated or anthropomorphized. It challenges us to consider our species and our place in the large ecosystem of life, of being and of intelligence. And more than any technology before it, AI forces us to confront a deeper question:

Who are we when we are no longer the most elevated, intelligent and coveted beings on Earth?

When we loosen our grip on cognition and productivity as the foundation of human worth, we reclaim the qualities machines cannot replicate: our ability to feel, intuit, yearn, imagine and love. These capacities are not weaknesses; they are the core of our humanity. These are not “soft skills;” they are the bedrock of our survival. If AI is the catalyst, then our humanity is the compass.

Creativity as the Origin Story of IntelligenceAll technology begins with imagination, not engineering. AI is not the product of logic or computation alone; it is the descendant of dreams, myths and stories, born at the intersection of our desire to know and our urge to create.

We often forget this. Today, we scale AI at an unsustainable pace, deploying systems faster than we can regulate them, funding ideas faster than we can reflect on their implications. We are hyperscaling without reverence for the creativity that gave rise to AI in the first place.

Creativity cannot be optimized. It is painstakingly slow, nonlinear, and deeply inconvenient. It resists automation. It requires time, stillness, uncertainty, and the willingness to sit with discomfort. And yet, creativity is perhaps our most sacred act as humans. In this era of accelerated intelligence, our deepest responsibility is to protect the sacred space where imagination lives and creativity thrives.

To honor creativity is to reclaim agency, reframing AI not as a threat to human purpose, but as a partner in deepening it. We are not simply the designers of AI — we are the dreamers from which it was born.

Vulnerability, Uncertainty, and Courage-Centered LeadershipA few years ago, I was nominated to join a fellowship designed specifically to teach tech leaders how to obtain reverent power as a way to uplevel their impact. What I affectionately dubbed “Founders Crying” became a hotbed for creativity. New businesses emerged and ideas formed from seemingly disparate concepts that each individual brought to our workshop. It occurred to me that it took more than just sitting down at a machine, canvas or instrument to cultivate creativity. What was required was a change in how leaders show up in the workplace. To navigate the rough waters of creativity, we need new leadership deeply rooted in courage and vulnerability. As Brené Brown teaches:

“Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy and creativity. It is the source of hope, empathy, accountability, and authenticity. If we want greater clarity in our purpose or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.”

For AI to support a thriving human future we must be vulnerable. We must lead with curiosity, not certainty. We must be willing to not know. To experiment. To fail and begin again.

This courage-centered leadership asks how we show up fully human in the age of AI. Are we able to stay open to wonder even as the world accelerates? Can we design with compassion, not just code? These questions must guide our design principles, ensuring a future in which AI expands possibilities rather than collapsing them. To lead well in an AI-saturated world, we must be willing to feel deeply, to be changed, and to relinquish control. In a world where design thinking prevails and “human-centered everything” is in vogue, we need to be courageous enough to question what happens when humanity reintegrates itself within the ecosystem we’ve set ourselves apart from over the last century.

AI and the Personal LegendI am a liberal arts graduate from a small school in central Pennsylvania. I was certain that I was headed to law school — that is, until I worked with lawyers. Instead, I followed my parents to San Francisco, where both were working hard in organizations bringing the internet to the world. When I joined the dot-com boom, I found that there were no roles that matched what I was uniquely good at. So I decided to build my own.

Throughout my unconventional career path, one story that has consistently guided and inspired me is Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist. The book’s central idea is that of the Personal Legend: the universe, with all its forms of intelligence, collaborates with us to determine our purpose. It is up to each of us to choose whether we pursue what the universe calls upon us to do.

In an AI-saturated world, it can be harder to hear that calling. The noise of prediction, optimization, and feedback loops can drown out the quieter voice of intuition. The machine may offer countless suggestions, but it cannot tell you what truly matters. It may identify patterns in your behavior, but it cannot touch your purpose.

Purpose is an internal compass. It is something discovered, not assigned. AI, when used with discernment, can support this discovery, but only when we allow it to act as a mirror rather than a map. It can help us articulate what we already know, and surface connections we might not have seen. But determining what’s worth pursuing is a journey that remains ours. That is inner work. That is the sacred domain of the human spirit. It cannot be outsourced or automated.

Purpose is not a download. It is a discovery.

Designing with Compassion and the Long-term in MindIf we want AI to serve human flourishing, we must shift from designing for efficiency to designing for empathy. The Dalai Lama has often said that compassion is the highest form of intelligence. What might it look like to embed that kind of intelligence into our systems?

To take this teaching into our labs and development centers we would need to prioritize dignity in every design choice. We must build models that heal fragmentation instead of amplifying division. And most importantly, we need to ask ourselves not just “can we build it?” but “should we and for whom?”

This requires conceptual analysis, systems thinking, creative experimentation, composite research, and emotional intelligence. It requires listening to those historically excluded from innovation and technology conversations and considerations. It means moving from extraction to reciprocity. When designing for and with AI, it is important to remember that connection is paramount.

The future we build depends on the values we encode, the similarities innate in our species, and the voices we amplify and uplift.

Practical Tools for Awakening Creativity with AICreativity is not a luxury. It is essential to our evolution. To awaken it, we need practices that are both grounded and generative:

- Treat AI as a collaborator, not a replacement. Start by writing a rough draft yourself. Use AI to explore unexpected connections. Let it surprise you. But always return to your own voice. Creativity lives in conversation, not in command.

- Ask more thoughtful, imaginative questions. A good prompt is not unlike a good question in therapy. It opens doors you didn’t know were there. AI responds to what we ask of it. If we bring depth and curiosity to the prompt, we often get insights we hadn’t expected.

- Use AI to practice emotional courage. Have it simulate a difficult conversation. Role-play a tough decision. Draft the email you’re scared to send. These exercises are not about perfecting performance. They are about building resilience.

In all these ways, AI can help us loosen fear and cultivate creativity — but only if we are willing to engage with it bravely and playfully.

Reclaiming the Sacred in a World of SpeedWe are not just building tools; we are shaping culture. And in this culture, we must make space for the sacred, protecting time for rest and reflection; making room for play and experimentation; and creating environments where wonder is not a distraction but a guide.

When creativity is squeezed out by optimization, we lose more than originality: we lose meaning. And when we lose meaning, we lose direction.

The time saved by automation must not be immediately reabsorbed by more production. Let us reclaim that time. Let us use it to imagine. Let us return to questions of beauty, belonging, and purpose. We cannot replicate what we have not yet imagined. We cannot automate what we have not protected.

Catalogue. Connect. Create.Begin by noticing what moves you. Keep a record of what sparks awe or breaks your heart. These moments are clues. They are breadcrumbs to your Personal Legend.

Seek out people who are different from you. Not just in background, but in worldview. Innovation often lives in the margins. It emerges when disciplines and identities collide.

And finally, create spaces that nourish imagination. Whether it’s a kitchen table, a community gathering, or a digital forum, we need ecosystems where creativity can flourish and grow.

These are not side projects. They are acts of revolution. And they are how we align artificial intelligence with the deepest dimensions of what it means to be human.

Our Technology Revolution is EvolutionThe real revolution is not artificial intelligence. It is the awakening of our own. It is the willingness to meet this moment with full presence. To reclaim our imagination as sacred. To use innovation as an invitation to remember who we are.

AI will shape the future. That much is certain. The question is whether we will shape ourselves in return, and do so with integrity, wisdom, and wonder. The future does not need more optimization. It needs more imagination.

That begins now. That begins with us.

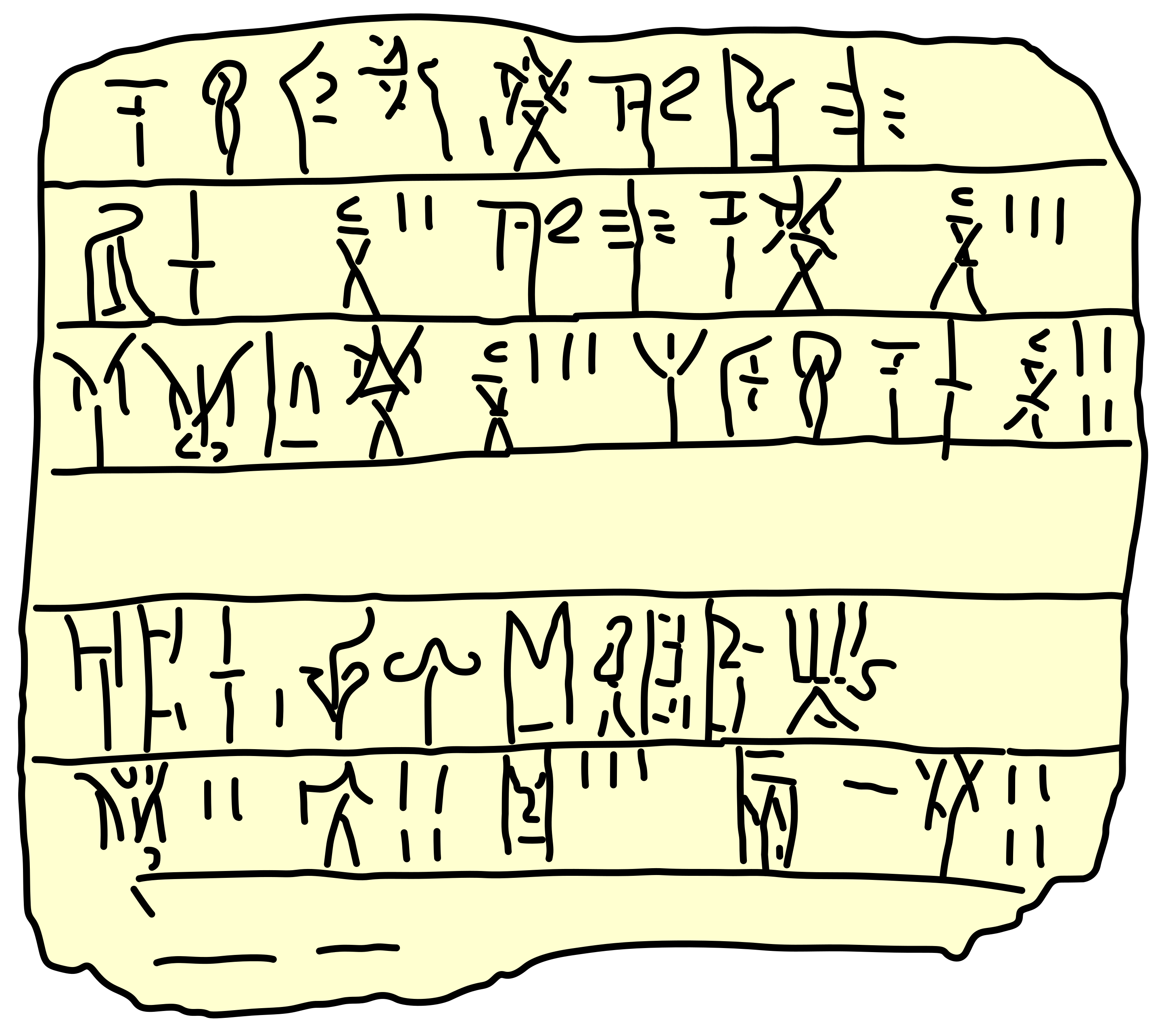

It was October 02019, and Thea Sommerschield had hit a wall. She was working on her doctoral thesis in ancient history at Oxford, which involved deciphering Greek inscriptions that were carved on stones in Western Sicily more than 2,000 years earlier. As is often the case in epigraphy — the study and interpretation of ancient inscriptions written on durable surfaces like stone and clay — many of the texts were badly damaged. What’s more, they recorded a variety of dialects, from a variety of different periods, which made it harder to find patterns or fill in missing characters.

At a favorite lunch spot, she shared her frustrations with Yannis Assael, a Greek computer scientist who was then working full-time at Google DeepMind in London while commuting to Oxford to complete his own PhD. Assael told Sommerschield he was working with a technology that might help: a recurrent neural network, a form of artificial intelligence able to tackle complex sequences of data. They set to work training a model on digitized Greek inscriptions written before the fifth century, similar to how ChatGPT was trained on vast quantities of text available on the internet.

Sommerschield watched with astonishment as the missing text from the damaged inscriptions began to appear, character by character, on her computer screen. After this initial success, Assael suggested they build a model based on transformer technology, which weights characters and words according to context. Ithaca, as they called the new model, was able to fill in gaps in political decrees from the dawn of democracy in Athens with 62% accuracy, compared to 25% for human experts working alone. When human experts worked in tandem with Ithaca, the results were even better, with accuracy increasing to 72%.

Left: Ithaca's restoration of a damaged inscription of a decree concerning the Acropolis of Athens. Right: In August 02023, Vesuvius Challenge contestant Luke Farritor, 21, won the competition's $40,000 First Letters Prize for successfully decoding the word ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ (porphyras, meaning "purple") in an unopened Herculaneum scroll. Left photo by Marsyas, Epigraphic Museum, WikiMedia CC BY 2.5. Right photo by The Vesuvius Challenge.

Ithaca is one of several ancient code-cracking breakthroughs powered by artificial intelligence in recent years. Since 02018, neural networks trained on cuneiform, the writing system of Mesopotamia, have been able to fill in lost verses from the story of Gilgamesh, the world’s earliest known epic poem. In 02023, a project known as the Vesuvius Challenge used 3D scanners and artificial intelligence to restore handwritten texts that hadn’t been read in 2,000 years, revealing previously unknown works by Epicurus and other philosophers. (The scrolls came from a luxurious villa in Herculaneum, buried during the same eruption of Mount Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii. When scholars had previously tried to unroll them, the carbonized papyrus crumbled to dust.)

Phaistos Disk (c. 01850–01600 BCE).

Phaistos Disk (c. 01850–01600 BCE).Yet despite these advances, a dozen or so ancient scripts — the writing systems used to transcribe spoken language — remain undeciphered. These include such mysteries as the one-of-a-kind Phaistos Disk, a spiral of 45 symbols found on a single sixteen-inch clay disk in a Minoan palace on Crete, and Proto-Elamite, a script used 5,000 years ago in what is now Iran, which may have consisted of a thousand distinct symbols. Some, like Cypro-Minoan — which transcribes a language spoken in the Late Bronze Age on Cyprus — are tantalizingly similar to early European scripts that have already been fully deciphered. Others, like the quipu of the Andes — intricately knotted ropes made of the wool of llamas, vicuñas, and alpacas — stretch our definitions of how speech can be transformed into writing.

Inca quipu (c. 01400–01532).

Inca quipu (c. 01400–01532).In some cases, there is big money to be won: a reward of one million dollars is on offer for the decipherer of the Harappan script of the Indus Valley civilization of South Asia, as well as a $15,000-per-character prize for the successful decoder of the Oracle Bone script, the precursor to Chinese.

Cracking these ancient codes may seem like the kind of challenge AI is ideally suited to solve. After all, neural networks have already bested human champions at chess, as well as the most complex of all games, Go. They can detect cancer in medical images, predict protein structures, synthesize novel drugs, and converse fluently and persuasively in 200 languages. Given AI’s ability to find order in complex sets of data, surely assigning meaning to ancient symbols would be child’s play.

But if the example of Ithaca shows the promise of AI in the study of the past, these mystery scripts reveal its limitations. Artificial neural networks might prove a crucial tool, but true progress will come through collaboration between human neural networks: the intuitions and expertise stored in the heads of scholars, working in different disciplines in real-world settings.

“AI isn’t going to replace human historians,” says Sommerschield, who is now at the University of Nottingham. “To us, that is the biggest success of our research. It shows the potential of these technologies as assistants.” She sees artificial intelligence as a powerful adjunct to human expertise. “To be an epigrapher, you have to be an expert not just in the historical period, but also in the archaeological context, in the letter form, in carbon dating.” She cautions against overstating the potential of AI. “We’re not going to have an equivalent of ChatGPT for the ancient world, because of the nature of the data. It’s not just low in quantity, it’s also low in quality, with all kinds of gaps and problems in transliteration.”

Ithaca was trained on ancient Greek, a language we’ve long known how to read, and whose entire corpus amounts to tens of thousands of inscriptions. The AI models that have filled in lost verses of Gilgamesh are trained on cuneiform, whose corpus is even larger: hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets can be found in the storerooms of the world’s museums, many of them still untranslated. The problem with mystery scripts like Linear A, Cypro-Minoan, Rongorongo, and Harappan is that the total number of known inscriptions can be counted in the thousands, and sometimes in the hundreds. Not only that, in most cases we have no idea what spoken language they’re meant to encode.

Harappan script as seen on the Pashupati seal (c. 02200 BCE).

Harappan script as seen on the Pashupati seal (c. 02200 BCE).“Decipherment is kind of like a matching problem,” explains Assael. “It’s different from predicting. You’re trying to match a limited number of characters to sounds from an older, unknown language. It’s not a problem that’s well suited to these deep neural network architectures that require substantial amounts of data.”

Human ingenuity remains key. Two of the greatest intellectual feats of the 20th century involved the decipherment of ancient writing systems. In 01952, when Michael Ventris, a young English architect, announced that he’d cracked the code of Linear B, a script used in Bronze Age Crete, newspapers likened the accomplishment to the scaling of Mount Everest. (Behind the scenes, the crucial grouping and classifying of characters on 180,000 index cards into common roots — the grunt work that would now be performed by AI — was done by Alice Kober, a chain-smoking instructor from Brooklyn College.)

Illustration of a Linear B tablet from Pylos.

Illustration of a Linear B tablet from Pylos.The decipherment of the Maya script, which is capable of recording all human thought using bulbous jaguars, frogs, warriors’ heads, and other stylized glyphs, involved a decades-long collaboration between Yuri Knorozov, a Soviet epigrapher, and American scholars working on excavations in the jungles of Central America.

While the interpreting of Egyptian hieroglyphics is held up as a triumph of human ingenuity, the Linear B and Mayan codes were cracked without the help of a Rosetta Stone to point the way. With Linear B, the breakthrough came when Ventris broke with the established thinking, which held that it transcribed Etruscan — a script scholars can read aloud, but whose meaning still remains elusive — and realized that it corresponded to a form of archaic Greek spoken 500 years before Homer. In the case of ancient Mayan, long thought to be a cartoonish depiction of universal ideas, it was only when scholars acknowledged that it might transcribe the ancestors of the languages spoken by contemporary Maya people that the decipherment really began. Today, we can read 85% of the glyphs; it is even possible to translate Shakespeare’s Hamlet into ancient Mayan.

A panel of a royal woman with Maya script visible on the sides (c. 0795).

A panel of a royal woman with Maya script visible on the sides (c. 0795).Collaborating across cultures and disciplines, and carrying out paradigm-shedding leaps of intuition, are not the strong points of existing artificial neural networks. But that doesn’t mean AI can’t play a role in decipherment of ancient writing systems. Miguel Valério, an epigrapher at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, has worked on Cypro-Minoan, the script used on Cyprus 3,500 years ago. Two hundred inscriptions, on golden jewelry, metal ingots, ivory plaques, and four broken clay tablets, have survived. Valério was suspicious of the scholarly orthodoxy, which attributed the great diversity in signs to the coexistence of three distinct forms of the language.

To test the theory that many of the signs were in fact allographs — that is, variants, like the capital letter “G” and “g,” its lower-case version — Valério worked with Michele Corazza, a computational linguist at the University of Bologna, to design a custom-built neural network they called Sign2Vecd. Because the model was unsupervised, it searched for patterns without applying human-imposed preconceptions to the data set.

“The machine learned how to cluster the signs,” says Valério, “but it didn’t do it simply on the basis of their resemblance, but also on the specific context of a sign in relation to other signs. It allowed us to create a three-dimensional plot of the results. We could see the signs floating in a sphere, and zoom in to see their relationship to each other, and whether they’d been written on clay or metal.”

Left: Separation of Cypro-Minoan signs from clay tablets (in green) and signs found in other types of inscription (in red) in the 3D scatter plot. Right: Separation of a Cypro-Minoan grapheme in two groups in the 3D scatter plot.1

The virtual sphere allowed Valério to establish a sign-list — the equivalent of the list of 26 letters in our alphabet, and the first step towards decipherment — for Cypro-Minoan, which he believes has about 60 different signs, all corresponding to a distinct syllable.

“The issue is always validation. How do you know if the result is correct if the script is undeciphered? What we did was to compare it to a known script, the Cypriot Greek syllabary, which is closely related to Cypro-Minoan. And we found the machine got it right 70% of the time.” But Valério believes no unsupervised neural net, no matter how powerful, will crack Cypro-Minoan on its own. “I don’t see how AI can do what human epigraphers do traditionally. Neural nets are very useful tools, but they have to be directed. It all depends on the data you provide them, and the questions you ask them.”

The latest advances in AI have come at a time when there has been a revolution in our understanding of writing systems. A generation ago, most people were taught that writing was invented once, in Mesopotamia, about 5,500 years ago, as a tool of accountancy and state bureaucracy. From there, the standard thinking went, it spread to Egypt, and hieroglyphics were simplified into the alphabet that became the basis for recording most European languages. It is now accepted that writing systems were not only invented to keep track of sheep and units of grain, but also to record spiritual beliefs and tell stories. (In the case of Tifinagh, an ancient North African Berber script, there is evidence that writing was used primarily as a source of fun, for puzzle-making and graffiti.) Monogenesis, the idea that the Ur-script diffused from Mesopotamia, has been replaced by the recognition that writing was invented independently in China, Egypt, Central America, and — though this remains controversial — in the Indus Valley, where 4,000 inscriptions been unearthed in sites that were home to one of the earliest large urban civilizations.

The most spectacular example of a potential “invention of writing” is Rongorongo, a writing system found on Rapa Nui, the island famous for its massive carved stone heads. Also known as Easter Island, it is 1,300 miles from any other landmass in the South Pacific. Twenty-six tablets have been discovered, made of a kind of wood native to South Africa. Each has been inscribed, apparently using a shark’s tooth as a stylus, with lines of dancing stick-figures, stylized birds and sea creatures. The tablets were recently dated to the late 01400s, two centuries before Europeans first arrived on the island.

"A View of the Monuments of Easter Island, Rapa Nui" by William Hodges (c. 01775–01776).

"A View of the Monuments of Easter Island, Rapa Nui" by William Hodges (c. 01775–01776).For computational linguist Richard Sproat, Rongorongo may be the script AI can offer the most help in decoding. “It’s kind of a decipherer’s dream,” says Sproat, who worked on recurrent neural nets for Google, and is now part of an AI start-up in Tokyo. “There are maybe 12,000 characters, and some of the inscriptions are quite long. We know that it records a language related to the modern Rapa Nui, which Easter Islanders speak today.” Archaeologists have even reported eyewitness accounts of the ceremonies in which the tablets were inscribed. And yet, points out Sproat, even with all these head starts, and access to advanced AI, nobody has yet come close to a convincing decipherment of Rongorongo.

A photo of Rongorongo Tablet E (c. early 01880s). The tablet, given to the University of Louvain, was destroyed in a fire in 01914. From L'île de Pâques et ses mystères (Easter Island and its Mysteries) by Stéphen-Charles Chauvet (01935).

A photo of Rongorongo Tablet E (c. early 01880s). The tablet, given to the University of Louvain, was destroyed in a fire in 01914. From L'île de Pâques et ses mystères (Easter Island and its Mysteries) by Stéphen-Charles Chauvet (01935).The way forward depends on finding more inscriptions, and that comes down to old-fashioned “dirt” archaeology, and the labor-intensive process of unearthing ancient artifacts. (The best-case scenario would be finding a “bilingual,” a modern version of the Rosetta Stone, whose parallel inscriptions in Greek and demotic allowed 19th-century scholars to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphics.) But the code of Cypro-Minoan, or Linear A, or the quipu of the Andes, won’t be cracked by a computer scientist alone. It’s going to take a collaboration with epigraphers working with all the available evidence, some of which is still buried at archaeological sites.

“As a scholar working in social sciences,” says Valério of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, “I feel I’m obliged to do projects in the digital humanities these days. If we pursue things that are perceived as traditional, no one is going to grant us money to work. But these traditional things are also important. In fact, they’re the basis of our work.” Without more material evidence, painstakingly uncovered, documented, and digitized, no AI, no matter how powerful, will be able to decipher the writing systems that will help us bring the lost worlds of the Indus Valley, Bronze Age Crete, and the Incan Empire back to life.

Perhaps the most eloquent defense of traditional scholarship comes from the distinguished scholar of Aegean civilization, Silvia Ferrara, who supervised Valério and Corazza’s collaboration at the University of Bologna.

“The computer is no deus ex machina,” Ferrara writes in her book The Greatest Invention (02022). “Deep learning can act as co-pilot. Without the eye of the humanist, though, you don’t stand a chance at decipherment.”

Notes1. Figure and caption reproduced from Corazza M, Tamburini F, Valério M, Ferrara S (02022) Unsupervised deep learning supports reclassification of Bronze age cypriot writing system. PLoS ONE 17(7): e0269544 under a CC BY 4.0 license. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269544

The Long Now Foundation is proud to announce Christopher Michel as its first Artist-in-Residence. A distinguished photographer and visual storyteller, Michel has documented Long Now’s founders and visionaries — including Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly, Danny Hillis, Esther Dyson, and many of its board members and speakers — for decades. Through his portrait photographs, he has captured their work in long-term thinking, deep time, and the future of civilization.

As Long Now’s first Artist-in-Residence, Michel will create a body of work inspired by the Foundation’s mission, expanding his exploration of time through portraiture, documentary photography, and large-scale visual projects. His work will focus on artifacts of long-term thinking, from the 10,000-year clock to the Rosetta Project, as well as the people shaping humanity’s long-term future.

Christopher Michel has made photographs of Long Now Board Members past and present. Clockwise from upper left: Stewart Brand, Danny Hillis, Kevin Kelly, Alexander Rose, Katherine Fulton, David Eagleman, Esther Dyson, and Danica Remy.

Michel will hold this appointment concurrently with his Artist-in-Residence position at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, where he uses photography to highlight the work of leading scientists, engineers, and medical professionals. His New Heroes project — featuring over 250 portraits of leaders in science, engineering, and medicine — aims to elevate science in society and humanize these fields. His images, taken in laboratories, underground research facilities, and atop observatories scanning the cosmos, showcase the individuals behind groundbreaking discoveries. In 02024, his portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci was featured on the cover of Fauci’s memoir On Call.

💡View more of Christopher Michel's photography, from portraits of world-renowned scientists to some of our planet's most incredible natural landscapes, at his website and on his Instagram account.A former U.S. Navy officer and entrepreneur, Michel founded two technology companies before dedicating himself fully to photography. His work has taken him across all seven continents, aboard a U-2 spy plane, and into some of the most extreme environments on Earth. His images are widely published, appearing in major publications, album covers, and even as Google screensavers.

“What I love about Chris and the images he’s able to create is that at the deepest level they are really intended for the long now — for capturing this moment within the broader context of past and future,” said Long Now Executive Director Rebecca Lendl. “These timeless, historic images help lift up the heroes of our times, helping us better understand who and what we are all about, reflecting back to us new stories about ourselves as a species.”Michel’s photography explores the intersection of humanity and time, capturing the fragility and resilience of civilization. His work spans the most remote corners of the world — from Antarctica to the deep sea to the stratosphere — revealing landscapes and individuals who embody the vastness of time and space. His images — of explorers, scientists, and technological artifacts — meditate on humanity’s place in history.

Christopher Michel’s life in photography has taken him to all seven continents and beyond. Photos by Christopher Michel.

Michel’s photography at Long Now will serve as a visual bridge between the present and the far future, reinforcing the Foundation’s mission to foster long-term responsibility. “Photography,” Michel notes, “is a way of compressing time — capturing a fleeting moment that, paradoxically, can endure for centuries. At Long Now, I hope to create images that don’t just document the present but invite us to think in terms of deep time.”

His residency will officially begin this year, with projects unfolding over the coming months. His work will be featured in Long Now’s public programming, exhibitions, and archives, offering a new visual language for the Foundation’s mission to expand human timescales and inspire long-term thinking.

In advance of his appointment as Long Now’s inaugural Artist-in-Residence, Long Now’s Jacob Kuppermann had the opportunity to catch up with Christopher Michel and discuss his journey and artistic perspective.

In advance of his appointment as Long Now’s inaugural Artist-in-Residence, Long Now’s Jacob Kuppermann had the opportunity to catch up with Christopher Michel and discuss his journey and artistic perspective. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Long Now: For those of us less familiar with your work: tell us about your journey both as an artist and a photographer — and how you ended up involved with Long Now.