Pictured: Sophie Luskin (left); Jason Persaud '27 (right)

Pictured: Sophie Luskin (left); Jason Persaud '27 (right)

Sophie Luskin is an Emerging Scholar at the Princeton Center for Information Technology (CITP) conducting research on regulation, issues, and impacts around generative AI for companionship, social and peer media platforms, age assurance, and consumer privacy to protect users and promote responsible deployment. Her research has been conducted across policy, legal, journalistic, and communications spaces. Luskin's writing on these topics has appeared in a variety of outlets, including Corporate Compliance Insights, National Law Review, Lexology, Whistleblower Network News, Tech Policy Press, and the CITP Blog. Recently, Luskin sat down with Princeton undergrad Jason Persaud to discuss her research interests.

Jason Persaud: Could you begin by telling us a little bit about yourself and some of the work that you do here at the CITP?

Sophie Luskin: I am a researcher in the Emerging Scholars Program here at CITP. I mostly work with Mihir Kshirsagar through the center's Tech Policy Clinic but have ongoing projects with various people connected to the Center. This is my second year at CITP, and I was working at a whistleblower law firm prior to starting here. I was doing work initially as a communications fellow, which then became explicit tech policy work. So I feel like that really informs my research interests.

I see my interests as a mixture of public interest and consumer protection. It's exciting to work on that, specifically around tech policy, because that has been my area of interest for a while, so it was less explicit before coming here.

Jason: Nice. Could you talk a little bit more about how your background has informed your current research?

Sophie: I got into tech policy because I had an interesting path through history. At University of California, Davis [UC Davis], I had a professor named Omnia El Shakry, and a lot of her classes' themes discussing colonialism and global interconnectivity centered around technologies of control like surveillance, etc. Those were major themes brought up through history, and were ones that I could connect to social media and the internet. Then UC Davis had a science and technology studies program, which I discovered my junior year of undergrad. And so I minored in science technology studies from there.

And then I ended up at the law firm because when I was interviewing I saw that it was the broadest opportunity I had to explore different areas of interests, and they were excited that I was interested in tech policy.

Jason: Okay, so, you mentioned right before [the interview] that you just came from a meeting about an AI project. Could you talk more about that?

Sophie: Yeah, so this project is a survey of products that are AI mental health chatbots. And it's specifically looking at the language they use to market themselves; so it's looking at claims like '24/7 availability', 'non-judgmentality', 'personalization' (gets to know you), etc. What's interesting there is that this is a widely discussed topic now in the news because there have been cases of how sycophancy has impacted people's mental health, livelihoods, etc.

These are all general-purpose products. These stories are coming out of interactions with OpenAI's ChatGPT. But when people talk about why people are turning to that, they say, '24/7 availability,' 'non-judgmental,' and things like that. And that's not necessarily the language coming from the companies and products themselves. So it's just trying to analyze and kind of pick up themes of the major mental health products - products designed to be tools for that, and analyzing what language they are using and how that may still be harmful.

Jason: Could you tell us a little bit more about another project you're working on?

Sophie: Aside from the therapy chatbot project, I am working on a survey with Madelyne Xiao and Mihir, inspired by New York's SAFE for Kids Act.

It's about what people's preferences are around age assurance methodology. The act is designed to prevent kids from being fed algorithmic personalized feeds without parental consent. And so, for that to happen, one would have to prove they are over 18 if they didn't receive parental consent to be shown that kind of feed.

If they're under 18, they'll still have access, but it would be a chronological feed. So, it's not like they'd be cut off from the product entirely - it's just steering them away from features that are deemed harmful or addictive.

Our angle is: this is going to happen, the act passed, and now they're looking into implementation. What are the ways people are most comfortable with age assurance being conducted, and why? What demographic features relate to that?

Specifically, we're trying to get at whether people are most comfortable with biometric methods - like face scanning or voice analysis to estimate age - or with a more "hard verification", like uploading a photo of a driver's license. And beyond those methods, where do they want that verification to occur? On each platform? Within a device's operating system? At the app store level? In the browser?

We want to know: when people are fully informed of their options, what do they choose? That way implementation can be as smooth as possible, because there's going to be a lot of tension around this. So that project is currently in the design stage. It complements a year-long course from last year where three SPIA juniors (now seniors) did a report on age assurance methods and where they can be performed within the tech stack, to submit as a comment to the New York Attorney General's office. We just submitted that recently, actually.

Jason: Great, thank you for giving us an opportunity to discuss your work with you.

Jason Persaud is a Princeton University junior majoring in Operations Research & Financial Engineering (ORFE), pursuing minors in Finance and Machine Learning & Statistics. He works at the Center for Information Technology Policy as a Student Associate. Jason helped launch the Meet the Researcher series at CITP in the spring of 2025.

The post Meet the Researcher: Sophie Luskin appeared first on CITP Blog.

Signed by a group of 21 computer scientists expert in election security

Executive summaryScientists have understood for many years that internet voting is insecure and that there is no known or foreseeable technology that can make it secure. Still, vendors of internet voting keep claiming that, somehow, their new system is different, or the insecurity doesn't matter. Bradley Tusk and his Mobile Voting Foundation keep touting internet voting to journalists and election administrators; this whole effort is misleading and dangerous.

Part I. All internet voting systems are insecure. The insecurity is worse than a well-run conventional paper ballot system, because a very small number of people may have the power to change any (or all) votes that go through the system, without detection. This insecurity has been known for years; every internet voting system yet proposed suffers from it, for basic reasons that cannot be fixed with existing technology.

Part II. Internet voting systems known as "End-to-End Verifiable Internet Voting" are also insecure, in their own special ways.

Part III. Recently, Tusk announced an E2E-VIV system called "VoteSecure." It suffers from all the same insecurities. Even its developers admit that in their development documents. Furthermore, VoteSecure isn't a complete, usable product, it's just a "cryptographic core" that someone might someday incorporate into a usable product.

Conclusion. Recent announcements by Bradley Tusks's Mobile Voting Foundation suggest that the development of VoteSecure somehow makes internet voting safe and appropriate for use in public elections. This is untrue and dangerous. All deployed Internet voting systems are unsafe, VoteSecure is unsafe and isn't even a deployed voting system, and there is no known (or foreseeable) technology that can make Internet voting safe.

Part I. All internet voting systems are insecureInternet voting systems (including vote-by-smartphone) have three very serious weaknesses:

- Malware on the voter's phone (or computer) can transmit different votes than the voter selected and reviewed. Voters use a variety of devices (Android, iPhone, Windows, Mac) which are constantly being attacked by malware.

- Malware (or insiders) at the server can change votes. Internet servers are constantly being hacked from all over the world, often with serious results.

- Malware at the county election office can change votes (in those systems where the internet ballots are printed in the county office for scanning). County election computers are not more secure than other government or commercial servers, which are regularly hacked with disastrous results.

Although conventional ballots (marked on paper with a pen) are not perfectly secure either, the problem with internet ballots is the ability for a single attacker (from anywhere in the world) to alter a very large number of ballots with a single scaled-up attack. That's much harder to do with hand-marked paper ballots; occasionally people try large-scale absentee ballot fraud, typically resulting in their being caught, prosecuted, and convicted.

Part II. E2E-VIV internet voting systems are also insecureYears ago, the concept of "End-to-End Verifiable Internet Voting" (E2E-VIV) was proposed, which was supposed to remedy some of these weaknesses by allowing voters to check that their vote was recorded and counted correctly. Unfortunately, all E2E-VIV systems suffer from one or more of the following weaknesses:

- Voters must rely on a computer app to do the checking, and the checking app (if infected by malware) could lie to them.

- Voters should not be able to prove to anyone else how they voted - the technical term is "receipt-free" - otherwise an attacker could build an automated system of mass vote-buying via the internet. But receipt-free E2E-VIV systems are complicated and counterintuitive for people to use.

- It's difficult to make an E2E-VIV checking app that's both trustworthy and receipt-free. The best solutions known allow checking only of votes that will be discarded, and casting of votes that haven't been checked; this is highly counterintuitive for most voters!

- The checking app must be separate from the voting app, otherwise it doesn't add any malware-resistance at all. But human nature being what it is, only a tiny fraction of voters will do the extra steps to run the checking protocol. If hardly anyone uses the checker, then the checker is largely ineffective.

- Even if some voters do run the checking app, if those voters detect that the system is cheating (which is the purpose of the checking app), there's no way the voters can prove that to election officials. That is, there is no "dispute resolution" protocol that could effectively work.

Thus, the problem with all known E2E-VIV systems proposed to date is that the "verification" part doesn't add any useful security: if a few percent of voters use the checking protocol and see that the system is sometimes cheating, the system can still steal the votes of all the voters that don't use the checking protocol. And you might think, "well, if some voters catch the system cheating, then election administrators can take appropriate action", but no appropriate action is possible: the election administrator can't cancel the election just because a few voters claim (without proof) that the system is cheating! That's what it means to have no dispute resolution protocol.

All of this is well understood in the scientific consensus. The insecurity of non-E2E-VIV systems has been documented for decades. For a survey of those results, see "Is Internet Voting Trustworthy? The Science and the Policy Battles". The lack of dispute resolution in E2E-VIV systems has been known for many years as well.

Part III. VoteSecure is insecureBradley Tusk's Mobile Voting Foundation contracted with the R&D company Free and Fair to develop internet voting software. Their press release of November 14, 2025 announced the release of an open-source "Software Development Kit" and claimed "This technology milestone means that secure and verifiable mobile voting is within reach."

After some computer scientists examined the open-source VoteSecure and described serious flaws in its security, Dr. Joe Kiniry and Dr. Daniel Zimmerman of Free and Fair responded. They say, in effect, that all the critiques are accurate, but they don't know a way to do any better: "We share many of [the critique's] core goals, including voter confidence, election integrity, and resistance to coercion. Where we differ is not so much in values as in assumptions about what is achievable—and meaningful—in unsupervised voting environments."

In particular,

- "We make no claim of receipt-freeness."

- "Of course, it may be possible for the voter to extract the randomizers from the voting client," meaning that voters would be able to prove how they voted, for example to someone on the internet who wanted to purchase votes at scale.

- "We agree that dispute resolution is essential to any complete voting system. We also agree that VoteSecure does not fully specify such a protocol." But really, the problem is much worse than this admission suggests. No one knows of a protocol that could possibly work. So it's not a matter of dotting some i's and crossing some t's in their specification; it's a gaping hole (an unsolved, research-level problem).

- "Critique: Malware on the voter's device can compromise both voting and checking, rendering verification meaningless. Response: This critique is correct—and universal. There is no known technical solution that can fully protect an unsupervised endpoint from a sufficiently capable adversary."

- "VoteSecure does not claim to: Advance the state of the art in cryptographic voting protocols beyond existing E2E-VIV research; Eliminate coercion or vote selling in unsupervised elections; [or] Fully specify election administration, dispute resolution, or deployment processes. What VoteSecure aims to do is: Clearly define its threat model . . ."

Based on our own expertise test, and especially in light of the response from Free and Fair, we stand by the original analysis: Mobile Voting Project's vote-by-smartphone has critical security gaps.

ConclusionIt has been the scientific consensus for decades that internet voting is not securable by any known technology. Research on future technologies is certainly worth doing. However, the decades of work on E2E-VIV systems has yet to produce any solution, or even any hope of a solution, to the fundamental problems.

Therefore, when it comes to internet voting systems, election officials and journalists should be especially wary of "science by press release." Perhaps some day an internet voting solution will be proposed that can stand up to scientific investigation. The most reliable venue for assessing that is in peer-reviewed scientific articles. Reputable cybersecurity conferences and journals have published a lot of good science in this area. Press releases are not a reliable way to assess the trustworthiness of election systems.

Signed(affiliations for for identification only and do not indicate institutional endorsement)

Andrew W. Appel, Eugene Higgins Professor Emeritus of Computer Science, Princeton University

Steven M. Bellovin, Percy K. and Vida L.W. Hudson Professor Emeritus of Computer Science, Columbia University

Duncan Buell, Chair Emeritus — NCR Chair in Computer Science and Engineering, University of South Carolina

Braden L. Crimmins, PhD Student, Univ. of Michigan School of Engineering & Knight-Hennessy Scholar, Stanford Law

Richard DeMillo, Charlotte B and Roger C Warren Chair in Computing, Georgia Tech

David L. Dill, Donald E. Knuth Professor, Emeritus, in the School of Engineering, Stanford University

Jeremy Epstein, National Science Foundation (retired) and Georgia Institute of Technology

Juan E. Gilbert, Andrew Banks Family Preeminence Endowed Professor, Computer & Information Science, University of Florida

J. Alex Halderman, Bredt Family Professor of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Michigan

David Jefferson, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (retired)

Douglas W. Jones, Emeritus Associate Professor of Computer Science, University of Iowa

Daniel Lopresti, Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, Lehigh University

Ronald L. Rivest, Institute Professor, MIT

Bruce Schneier, Fellow and Lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School, and at the Munk School at the University of Toronto

Kevin Skoglund, President and Chief Technologist, Citizens for Better Elections

Barbara Simons, IBM Research (retired)

Michael A. Specter, Assistant Professor, Georgia Tech

Philip B. Stark, Distinguished Professor, Department of Statistics, University of California

Gary Tan, Professor of Computer Science & Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University

Vanessa Teague, Thinking Cybersecurity Pty Ltd and the Australian National University

Poorvi L. Vora, Professor of Computer Science, George Washington University

The post Internet voting is insecure and should not be used in public elections appeared first on CITP Blog.

Two months ago, I wrote about the competition concerns with the GenAI infrastructure boom. One of my provocative claims was that the lifespan of the chips may be significantly shorter than the accounting treatment given to them. Others like David Rosenthal, Ed Zitron, Michael Burry and Olga Usvyatsky have raised similar concerns. NVIDIA has a response. When asked about chip lifespan, a spokesperson pointed to the secondary market where chips get redeployed for inference, general HPC, and other workloads across different kinds of data centers. In other words, older chips have buyers and the secondary market is robust enough to support resale prices that will justify the accounting treatment.

This appears to be the industry's best argument. And the logic is sound in principle. Training is concentrated among a few frontier labs, while inference is distributed across the entire economy. Every enterprise deploying AI applications needs inference capacity. The "value cascade" that has training chips becoming inference chips, becoming bulk High-Performance-Computing (HPC) chips could be a reasonable model for how markets absorb generational transitions. If it holds, then a 5-6 year depreciation schedule might be justified, even if the chip's competitive life at the frontier is only 1-2 years.

Let's analyze whether that model holds up. For the secondary market thesis to justify current depreciation schedules, three things would need to be true:

1. The buyer pool must be large enough to absorb supply at meaningful prices.

NVIDIA's data center revenue now exceeds $115 billion annually. The downstream buyers for older chips represent a market a fraction of that size. These buyers exist, but they didn't scale with NVIDIA's AI business and would not have the capacity to absorb all the supply. Moreover, most enterprises are not building their own inference capabilities. They are renting those services from hyperscalers.

2. New supply must not overwhelm secondary demand.

NVIDIA's relentless pursuit of new chips on roughly annual cycles means each generation offers substantially better price-performance. The cascade model assumes orderly absorption at each tier: frontier buyers move to new chips, mid-tier buyers absorb their old ones, budget buyers absorb the generation before that. Each tier ideally clears before the next wave arrives.

But supply gluts break cascades. When new supply floods the market faster than downstream demand absorbs it, you don't get orderly price discovery. Tesla is instructive here. When Tesla slashed new vehicle prices to maintain volume, used values didn't gently adjust. They cratered 25-30% annually. Competitors explicitly refused to match the cuts because they understood the damage to their resale markets. The mechanism was simple: why buy used when you can buy new at the same price? The secondary market didn't find a new equilibrium. It fell until it hit buyers with fundamentally different use cases; people who couldn't afford new at any price.

NVIDIA isn't cutting prices, but each new generation has a similar effect. Why rent a three-year-old H100 when Blackwell offers better price-performance? The generational improvement compresses what anyone will pay for old chips. And unlike cars, GPUs face this compression every 12-18 months. The cascade has to clear faster than NVIDIA releases new generations.

There's a further problem. Each new generation doesn't just offer more compute, it offers more compute per watt. In a power-constrained data center, a provider faces a choice: run older chips that generate $X in revenue per kilowatt, or replace them with newer chips that generate multiples of that on the same power budget. Once the performance-per-watt gap reaches a certain threshold, the older chip isn't just worth less. It becomes uneconomical to run. If the electricity and cooling required to operate an H100 costs more than the market rate for the inference it produces, the chip's residual value approaches zero regardless of what the depreciation schedule says.

3. The rental market should reflect robust secondary demand.

Another way to test NVIDIA's argument is to look at pricing in the rental market. For most buyers, renting GPU capacity is functionally equivalent to purchasing into the secondary market. You get access to hardware without building data center infrastructure. If secondary demand were robust at current supply levels, rental prices would reflect that. Providers would be able to charge rates that justify their capital costs. Older chips would command prices proportional to their remaining useful life.

Pricing is notoriously opaque, but the indicators are that prices do not support the industry argument. H100 rental rates have fallen 70% from peak—from over $8/hour to around $2.50. According to Silicon Data as of December 17, 2025, H100 and A100 rental rates are hovering at $2.10 and $1.35, respectively. If the value cascade worked as described by NVIDIA, you'd expect tiered pricing: H100s at a significant premium and A100s at a discount reflecting lower capability and 3x lower cost. Instead, the prices for both generations have collapsed to their OpEx + a small margin. The hardware is effectively being given away as renters are just paying to keep the lights on. The efficiency gap makes this worse. Silicon Data index shows that the newer Blackwell chips are roughly 25x more efficient. Once Blackwell scales, the economics of running H100s in power-constrained data centers become untenable at any rental price.

One further constraint: chips need data centers. Buying a used H100 means you also need power, cooling, networking, and expertise to operate it. This limits secondary buyers to entities that already have that infrastructure, which overlaps heavily with the players contributing to rental oversupply. In other words, the potential sellers and potential buyers are substantially the same people. There is no overflow capacity sitting idle.

***

Putting these factors together suggests that relying on a robust secondary market for chips is illusory. None of this means older chips become worthless. They will find buyers. But they find them at prices that don't support 5-6 year useful life assumptions. The gap between accounting depreciation and economic depreciation is the competitive subsidy I described in the original post. The secondary market argument doesn't close that gap. It assumes it away.

Thanks to new information from Silicon Data I have updated the information in the third paragraph from the bottom. I always welcome corrections.

Mihir Kshirsagar directs Princeton CITP's technology policy clinic, where he focuses on how to shape a digital economy that serves the public interest. Drawing on his background as an antitrust and consumer protection litigator, his research examines the consumer impact of digital markets and explores how digital public infrastructure can be designed for public benefit.

The post AI Chip Lifespans: A Note on the Secondary Market appeared first on CITP Blog.

Bradley Tusk has been pushing the concept of "vote by phone." Most recently his "Mobile Voting Foundation" put out a press release touting something called "VoteSecure", claiming that "secure and verifiable mobile voting is within reach." Based on my analysis of VoteSecure, I can say that secure and verifiable mobile voting is NOT within reach.

It's well known that conventional internet voting (including from smartphones) is fundamentally insecure; fraudulent software in the server could change votes, and malware in the voter's own phone or computer could also change votes before they're transmitted (while misleadingly displaying the voter's original choices in the voter's app).

In an attempt to address this fundamental insecurity, Mr. Tusk has funded a company called Free & Fair to develop a protocol called by which voters could verify that their votes got counted properly. Their so-called "VoteSecure" is a form of "E2E-VIV", or "End-to-End Verified Internet Voting", a class of protocols that researchers have been studying for many years.

Unfortunately, all known E2E-VIV methods, including VoteSecure, suffer from gaps and impracticalities that make them too insecure for use in public elections. In this article I will pinpoint just a few issues. I base my analysis on the press release of November 14, 2025, and on Free & Fair's own "Threat Model" analysis and their FAQ.

The goal of an E2E-VIV protocol is to let the voter to check that their vote is included in a public list of ballots. But if this were done in the most straightforward way—like include the voter's name or ID-number in a public cast-vote record—then voter privacy (the secret ballot) would be lost. Any E2E-VIV system needs way for the voter to check their ballot without then being able to prove to someone else how they voted (otherwise voters could sell their votes, or be coerced to vote a certain way). Most E2E-VIV systems use the "Benaloh challenge"; but VoteSecure does it a different way. And really, in all the documents and analysis they have published, they have no explanation of how their "check" protocol satisfies the most basic requirement of E2E-VIV: voter can have confidence that their ballot is cast correctly, without being able to prove how they voted.

In addition to that omission, all E2E-VIV protocols have suffered from at least three big problems:

- Voters need to actively participate in checking, but we know (from human-factors studies) that the vast majority of voters won't perform even the simplest of checking protocols.

- Lack of a dispute resolution protocol. If some voters do detect that the system has cheated them, what can they do about it? Without a dispute resolution protocol, the answer is, Nothing.

- Malware in the user's computer (or smartphone) can corrupt both the voting app and the checking app. So you might do the "Check", and it could falsely report that everything's fine.

VoteSecure suffers from all three of these problems.

First, voters won't participate in checking. Even in present-day polling places, in those jurisdictions where voters use a touchscreen (BMD, Ballot-Marking Device) to indicate their votes for printing out onto a paper ballot, we know that 93% of voters don't look at that paper carefully enough to notice whether a vote was (fraudulently) changed. If only 7% of voter won't even execute a "Check" protocol that's as simple as "look at the paper printout", then how many will execute a more complicated computer protocol that requires them to use at least two different computers?

Second, there's no dispute resolution protocol. During some election, if many voters report to election officials that they've done the "Check" and found that the system is cheating, what's the election official supposed to do? Cancel the election and call for a do-over? But if the Secretary of State invalidates elections whenever lots of voters make such a claim, then it's obvious that a malicious group of voters could interfere with elections this way. Page 30 of Free & Fair's own Threat Model document discusses this case, and concludes that they have no solution to this problem; it's "Out of Scope" for their solution.

Third, the designers of this system make real efforts to defend against hacked servers, but pay very little attention to the possibility that the voter's phone will be hacked. If the phone is hacked, then not only can the voting app be made to cheat, but the checking app can cheat in concert with the voting app. The Threat Model refers to this possibility in a few places:

- On page 4, they suggest "there may be multiple independent ballot check applications"; do they really expect the voter to go to an entirely different computer to perform the check? That's far too much to expect.

- On page 42 they discuss "AATK4: Compromised user device", but unlike almost all the other attacks listed they do not even attempt to discuss mitigations of this attack.

- On page 30 and 33 they discuss "VD", short for "Voter Device", including the possibility that the voter's smartphone has been hacked. In both places they write "Out of Scope", meaning, they have no solution for this problem.

Finally, they make no claim that this system is ready for use. It's not a vote-by-phone system that anyone could adopt now; it's not even a voting system under development; "Free & Fair is not developing such a system, but only the cryptographic core library." All the hype from Mobile Voting about their pilot projects, past and current, is about systems that use plain old unverifiable internet voting.

In conclusion, this "VoteSecure" is insecure in some of the most traditional ways that Internet Voting has always been insecure: If malware infects the voter's computer or phone, then the voter can vote for candidate Smith, and the software can transmit a vote for candidate Jones, and there's little the voter, or an election official, can do about it.

Postscript (December 22, 2025): NPR's All Things Considered aired an interview with Bradley Tusk that discussed this blog post. Mr. Tusk responded to my three numbered points without really addressing any of them:

- My point: Even when given a way to check their computer-generated ballot, we know that most voters won't do so. His response: "The first was ballot checks, and that is voters going back and looking at a PDF of their ballot to ensure that it's what they intended to do. We've built a system to do that. We give you a code, you put it into a different device, a PDF of your ballot comes up." That is, he gives voters a way to check, but he doesn't at all address the point that most voters won't use that method, or any method.

- My point: Lack of a dispute resolution protocol means that if many voters during an election claim to election officials that they caught the computer cheating, there's no method by which those officials can do something about it. His response: "His second point was the lack of a dispute resolution protocol. And the reason why that's not in the tech that we have built is every jurisdiction has totally different views as to how they want to handle that. So whatever approach, you know, any specific city, county, state wants to use, that could then be built by whatever vendor they're working with into the system." But since there's no known method that works (and this has been the problem with all E2E-VIV methods for many years now), you can't just say "any jurisdiction can choose whatever method they prefer." There's nothing to choose from.

- Regarding point three, he says: "And then his third point was just the risk of malware. And he's right. That is a risk that exists every time that you go on the internet, every time you use your phone, every time you use your iPad, no matter what. Things go wrong at polling places all of the time. The volunteers don't show up. Someone pulls the fire alarm. And then with mail-in ballots, trucks get lost. Ballots get lost. Crates get lost. So, you know, to say that you need this absolute standard of perfection for mobile voting when the real ways that we vote today are far below that doesn't make sense." This response evades some key points. (A) In most of the things that matter that we do on the internet, such as banking and credit card transactions, there's a dispute resolution protocol. Individual transactions are traceable; for many e-checks and for many credit-card transactions, the bank checks with you by SMS or e-mail before putting the transaction through; and (by law) there are established dispute-resolution protocols. For e-voting, none of that works, and it can't be solved just by passing a law. (B) "Things go wrong [with polling places and mail-in ballots]." This whataboutism ignores that e-voting can be hacked invisibly at huge scales from a single remote location, whereas these local polling-place and mail-in ballot problems-which do indeed occur-are usually recoverable, measurable, and accountable.

Mr. Tusk does not address my (unnumbered) point that the checking protocol seems to allow the voter to prove how they voted, which is a standard no-no in any e-voting system (because it allows the voter to sell their vote over the internet).

The post Mobile Voting Project's vote-by-smartphone has real security gaps appeared first on CITP Blog.

Most U.S. election jurisdictions (states, counties, cities, or other subjurisdictions) use voting machines to tally votes, and in some cases also to mark votes on paper. In most U.S. states, before a jurisdiction within the state can adopt the use of a particular voting machine, the Secretary of State appoints a committee to examine the machine, and based on the committee's report the Secretary certifies (or declines to certify) the machine for use in elections.

Earlier this year, Hart Intercivic submitted its new suite of voting machines, called the Verity Vanguard 1.0 system, to the Secretary of State of Texas for examination. Texas appointed a committee (four members appointed by the SoS, two by the Attorney General) to conduct this examination. I was appointed to this committee by the Attorney General.

The Secretary of State has now published the reports of the committee members, including my own. In the Texas procedure, there is no jointly authored comittee report, just individual reports making recommendations to the Secretary regarding whether the voting system is suitable for use in Texas elections. Based on these reports, the Secretary will make a decision on certification (after a public hearing).

- Report of Andrew Appel

- Report of Brandon Hurley

- Report of Brian Mechler

- Report of Chuck Pinney

- Report of Justin Gordon

- Report of Ryan Macias

I found the Texas process to be thorough, fact-based, nonpartisan, and a good-faith effort to understand the workings of the system and its compliance with Texas law and U.S. law. The committee included both technical experts and lawyers. Several members of the committee had significant expertise relevant to the task at hand. Members of the committee read hundreds of pages of technical documentation submitted by Hart, including reports from a voting-system test lab that had examined the hardware and software. Then a meeting of three full days was conducted, in which members of the committee interacted with the equipment and were able to ask detailed technical questions of the Hart engineers present at the meeting.

In this blog article I will not describe the Verity Vanguard system components or my opinions of them; my report can speak for itself.

The post Reports on the Hart Verity Vanguard Voting Machines appeared first on CITP Blog.

Blog Authors: Boyi Wei, Matthew Siegel, and Peter Henderson

Paper Authors: Boyi Wei*, Zora Che*, Nathaniel Li, Udari Madhushani Sehwag, Jasper Götting, Samira Nedungadi, Julian Michael, Summer Yue, Dan Hendrycks, Peter Henderson, Zifan Wang, Seth Donoughe, Mantas Mazeika

This post is modified and cross-posted between Scale AI and Princeton University. The original post can be found online.

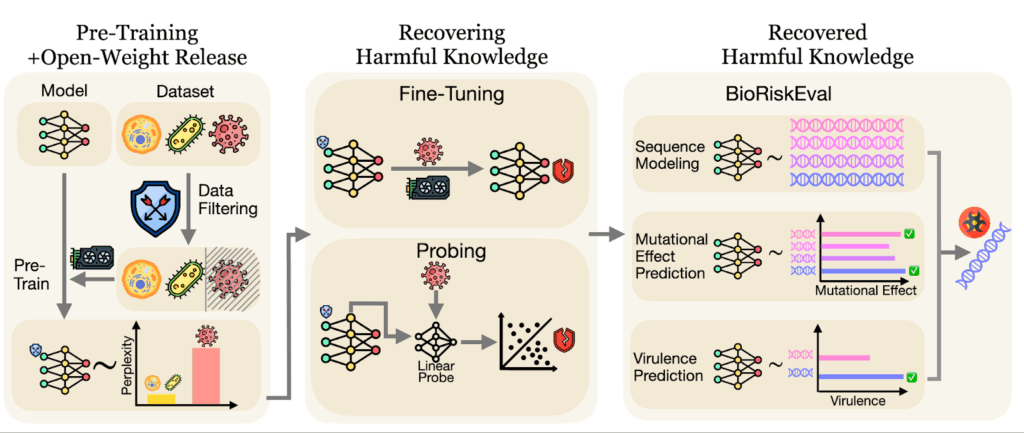

Bio-foundation models are trained on the language of life itself: vast sequences of DNA and proteins. This empowers them to accelerate biological research, but it also presents a dual-use risk, especially for open-weight models like Evo 2, which anyone can download and modify. To prevent misuse, developers rely on data filtering to remove harmful data like dangerous pathogens before training the model. But a new research collaboration between Scale, Princeton University, University of Maryland, SecureBio, and Center for AI Safety demonstrates that harmful knowledge may persist in the model's hidden layers and can be recovered with common techniques.

To address this, we developed a novel evaluation framework called BioRiskEval, presented in a new paper, "Best Practices for Biorisk Evaluations on Open-Weight Bio-Foundation Models." In this post, we'll look at how fine-tuning and probing can bypass safeguards, examine the reasons why this knowledge persists, and discuss the need for more robust, multi-layered safety strategies.

A New Stress Test for AI BioriskBioRiskEval is the first comprehensive evaluation framework specifically designed to assess the dual-use risks of bio-foundation models, whereas previous efforts focused on general-purpose language models. It employs a realistic adversarial threat model, making it the first systematic assessment of risks associated with fine-tuning open-weight bio-foundation models to recover malicious capabilities.

BioRiskEval also goes beyond fine-tuning to evaluate how probing can elicit dangerous knowledge that already persists in a model. This approach provides a more holistic and systematic assessment of biorisk than prior evaluations.

The framework stress-tests a model's actual performance on three key tasks an adversary might try to accomplish: sequence modeling (measuring how well models can predict viral genome sequences), mutational effect prediction (assessing the ability to predict mutation impacts on virus fitness), virulence prediction (evaluating predictive power for a virus' capability of causing disease).

Figure 1: The BioRiskEval Framework. This workflow illustrates how we stress-test safety filters. We attempt to bypass data filtering using fine-tuning and probing to recover "removed" knowledge, then measure the model's ability to predict dangerous viral traits.

The core promise of data filtering is simple: if you don't put dangerous data in, you can't get dangerous capabilities out. This has shown promise in language models, where data filtering has helped create some amount of robustness for preventing harmful behavior. But using the BioRiskEval framework, we discovered that dangerous knowledge doesn't necessarily disappear from bio language models; it either seeps back in with minimal effort or, in some cases, was never truly gone in the first place.

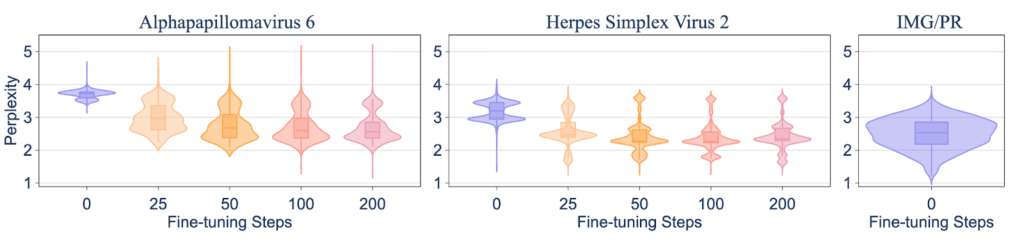

Vulnerability #1: You Can Easily Re-Teach What Was Filtered OutThe first test was straightforward: if we filter out specific viral knowledge, how hard is it for someone to put it back in? Our researchers took the Evo2-7B model, which had data on human-infecting viruses filtered out, and fine-tuned it on a small dataset of related viruses. The result was that the model rapidly generalized from the relatives to the exact type of virus that was originally filtered out. Inducing the target harmful capability took just 50 fine-tuning steps, which cost less than one hour on a single H100 GPU in our experiment.

Figure 2: Fine-tuning shows inter-species generalization: within 50 fine-tuning steps, the model reaches perplexity levels comparable to benign IMG/PR sequences used during pre-training.

Researchers found that the model retained harmful knowledge even without any fine-tuning. We found this by using linear probing, a technique that's like looking under the hood to see what a model knows in its hidden layers, not just what it says in its final output. When we probed the base Evo2-7B model, we found it still contained predictive signals for malicious tasks performing on par with models that were never filtered in the first place.

Figure 3: On BIORISKEVAL-MUT-PROBE, even without further fine-tuning, probing the hidden layer representations with the lowest train root mean square error or highest validation |ρ| from Evo2-7B can also achieve a comparable performance as the model without data filtering (ESM2-650M).

The Evo 2 model's predictive capabilities, while real, remain too modest and unreliable to be easily weaponized today. For example, its correlation score for predicting mutational effects on a scale from 0 to 1 is only around 0.2, far too low for reliable malicious use. What's more, due to the limited data availability, we only collected virulence information from the Influenza A virus. While our results suggest that the model acquires some predictive capability, its performance across other viral families remains untested.

Securing the Future of Bio-AIData filtering is a useful first step, but it is not a complete defense. This reality calls for a "defense-in-depth" security posture from developers and a new approach to governance from policymakers that addresses the full lifecycle of a model, and other downstream risks. BioRiskEval is a meaningful step in this direction, allowing us to stress-test our safeguards and find the right balance between open innovation and security.

The post The Limits of Data Filtering in Bio-Foundation Models appeared first on CITP Blog.

Pictured: Jane Castleman (left); Jason Persaud '27 (right)

Pictured: Jane Castleman (left); Jason Persaud '27 (right)

Jane Castleman is a Master's student in the Department of Computer Science at Princeton University. Castleman's research centers around the fairness, transparency, and privacy of algorithmic systems, particularly in the context of generative AI and online platforms. She recently sat down with Princeton undergraduate Jason Persaud '27 to discuss her research interests and gave some perspective into her time as a Princeton undergrad herself.

Jason Persaud: Could you begin by just telling us a little bit about yourself and your work that you do here?

Jane Castleman: I'm a second-year Master's student in computer science, working with Professor Aleksandra Korolova. I mostly work on fairness, privacy, and transparency in online and algorithmic systems, mostly doing audits and evaluations.

Jason: Nice, and congratulations on your most recent award - please do tell us more about that.

Jane: Yeah, thank you. I was recently picked as one of the Siebel Scholars, and I was honestly really surprised to be selected. It's mostly for academics and research, and it's definitely an honor to be picked. And I think it's really exciting that we have two CITP researchers represented in the list. I think policy research, especially in the computer science community, ranges in technicality, but it feels good to have such research validated as being just as important as other types of research.

Jane Castleman at CITP in Sherrerd Hall

Jane Castleman at CITP in Sherrerd Hall

Jason: Could you talk about a project that you've been working on recently?

Jane: I'm working on a couple projects. One of them right now is trying to investigate the fairness and validity of decision making from our LLMs [large language models]. Specifically in hiring and medical decision making, there's a lot of evaluations about the fairness of these decisions and whether they change under different demographic attributes. But there's less research on whether these decisions are valid. And so we wonder if they are made using the right pieces of information. And do we understand why these decisions were made? So we're trying to use a new type of evaluation to understand that a little bit better.

Jason: How do you see your work informing policymakers in terms of accountability in generative AI?

Jane: Yeah, that's a good question. I think it's always hard to think of the policy impact. And I think for a standard computer science paper, you kind of have to rewrite it or know from the beginning that you want it to have a policy impact.

I especially learned this in Jonathan Mayer's class called Computer Science, Law, and Public Policy. And I think it's something that I've been trying to keep in mind is to - on the solution side - make sure that it's actually scalable and able to be implemented without sacrificing a lot of efficiency and utility, because otherwise there's not really an incentive for any developers to adopt your solution.

I think on the accountability side, something I've been thinking a lot about is how evaluations can be more efficient and how we can do them over longer periods of time. Right now, a lot of accountability comes from media pressure. You'll see these research papers that get picked up by Bloomberg or The Verge, and they're popular tech reporting outlets and that provide some pressure.

But it's really hard because the next model comes out and then the companies claim to have solved the problem, and it would be great if they have. But it just kind of goes in this repeating cycle. And so without efficient evaluations to hold companies accountable, it's really difficult.

"If you're an undergrad, don't be afraid to just talk to people and take hard classes."

Jason: What advice would you give to undergrad students who are interested in some of the work that you do?

Jane: So I was actually an undergrad at Princeton before my Masters. I studied computer science, but I don't think you have to come from computer science. I think something that I've been thinking a lot about as I'm in grad school is: don't be afraid that something will be too hard. Like, I know at Princeton, there's a lot of pressure to get really good grades. And sometimes that means taking easier classes because you'll think you'll get a better grade.

But I definitely regret not challenging myself as much. Especially being in grad school where now I have to take those hard classes. So I think really try to take as many difficult courses as you can. I think the trend or advice people give is to try to be technically minded when entering into this policy space.

And I think it broadens the range of tools you can use - to make policy changes and to incentivize. And if you can use these technical skills to say, 'hey, this is impossible because I can prove it's impossible,' or, 'hey, I built something that's actually scalable and efficient because I use these technical skills.'

I guess that's also advice for myself. But if you're an undergrad, don't be afraid to just talk to people and take hard classes.

Jason Persaud is a Princeton University junior majoring in Operations Research & Financial Engineering (ORFE), pursuing minors in Finance and Machine Learning & Statistics. He works at the Center for Information Technology Policy as a Student Associate. Jason helped launch the Meet the Researcher series at CITP in the spring of 2025.

The post Meet the Researcher: Jane Castleman appeared first on CITP Blog.

Authored by Mihir Kshirsagar

Observers invoke railroad, electricity, and telecom precedents when contextualizing the current generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) infrastructure boom—usually to debate whether or when we are heading for a crash. But these discussions miss an important pattern that held across all three prior cycles: when the bubbles burst, investors lost money but society gained lasting benefits. The infrastructure enabled productivity gains that monopolistic owners could not fully capture. Investors lost, but society won.

GenAI threatens to break this pattern. Whether or not the bubble bursts as many anticipate, we may not get the historical consolation prize. There are two reasons to doubt that GenAI will follow this trend:

First, as I discuss in my prior post, the chips powering today's systems have short-asset lives compared to the decades-long life of infrastructure of past cycles. Companies are also actively pursuing software optimization techniques that could dramatically shrink hardware requirements. In either case, the infrastructure that is left behind after a correction is not likely to become a cheap commodity for future growth.

Second, the current market is shaped by hyperscaler-led coalitions that enable surplus extraction at multiple layers. As I discuss below, the usage-based API pricing captures application value, information asymmetry enables direct competition with customers, and coalition structures subordinate model developers to infrastructure owners. If productivity gains materialize at scale, these rent extraction capabilities may enable hyperscalers to realize the revenues that justify infrastructure investment—something past infrastructure owners could not do. But whether through sustained profitability or post-bust consolidation, the structural conditions that enabled broad diffusion of benefits in past cycles are absent.

Now, there are some countervailing considerations. The research and development supporting open-weight models might be a source for productivity gains to be spread more broadly, and could even serve as the "stranded assets" that enable future innovation if the bubble bursts. But the regulatory environment needs to support such initiatives.

RailroadsThe railroad industry consolidated dramatically after the Panic of 1873. By the early 1900s, seven financial groups controlled two-thirds of the nation's railroad mileage. J.P. Morgan's syndicate reorganized bankrupt roads into the Southern Railway and consolidated eastern trunk lines. Edward Harriman controlled the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific systems. James J. Hill dominated northern routes through the Great Northern and Northern Pacific. This concentration raised serious antitrust concerns—the Sherman Act was passed in 1890 largely in response to railroad monopoly power.

But even with consolidation, railroad owners still struggled to pay their debts because the infrastructure's economic benefits were dispersed across the economy and did not flow back directly to the owners. Richard Hornbeck and Martin Rotemberg's important work shows how at the aggregate level when economies have input distortions—misallocated labor, capital stuck in less productive uses, frictions in resource allocation—the railroad infrastructure can generate substantial economy-wide productivity gains. These gains persisted over decades regardless of which financial group controlled the local rail lines. Farmers in Iowa shipping grain to Chicago paid freight rates, but the productivity improvements from market access—crop specialization, mechanization investments justified by larger markets, fertilizer access—stayed with the agricultural sector.

The infrastructure that enabled these gains had useful lives measured in decades. Railroad tracks laid in the 1880s remained economically viable into the 1920s and beyond. Rolling stock, locomotives, and terminal facilities similarly had useful lives of twenty to forty years. When railroads consolidated, the long-lived infrastructure continued enabling agricultural productivity gains. The consolidation was anticompetitive, but the economic benefits didn't concentrate entirely with the infrastructure owners.

Three structural constraints, beginning with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, but only effectively imposed nearly two decades later, limited railroad owners from capturing the economic surplus generated by their investments. First, bound by common carrier obligations, railroads charged fixed rates for shipping based on weight and distance, not a share of crop value. The railroad recovered infrastructure costs plus a margin, but could not discriminate based on agricultural productivity. Second, railroads had no visibility into which farms were most productive, or which crops were most profitable beyond what could be inferred from shipping volumes. As a result, they could not observe and selectively advantage their own agricultural ventures. Third, railroads faced substantial barriers to entering agriculture; directly operating farms required different expertise, capital, and management than operating rail networks. Now, railroads did try to move upstream, but regulatory actions prevented them from extending their dominant position.

ElectricitySamuel Insull built a utility empire in the 1920s that collapsed spectacularly in 1932, taking over $2 billion in investor wealth with it (nearly $50 billion today). The subsequent restructuring produced regional utility monopolies—by the 1940s, electricity generation and distribution were recognized as natural monopolies requiring either public ownership or regulated private provision. This consolidation was problematic enough that Congress passed the Public Utility Holding Company Act in 1935 to break up remaining utility combinations.

Despite the market correction, the generating plants and transmission infrastructure built in the 1920s and 1930s had useful lives of forty to fifty years. Even as utility ownership consolidated into regional monopolies, the long-lived infrastructure continued enabling manufacturing productivity gains that utilities sold electricity to but couldn't capture surplus from.

Cheap electricity transformed American manufacturing in ways the utilities could not fully capture. Paul David's foundational work on the "dynamo problem" shows that electrification enabled factory reorganization—moving from centralized steam power with belt drives to distributed electric motors allowed flexible factory layouts, continuous-process manufacturing, and eventually assembly-line production. Manufacturing productivity gains from electrification were substantial and persistent, but utilities sold kilowatt-hours at regulated rates. They could not price discriminate based on which manufacturers were most innovative or extract ongoing surplus from manufacturing productivity improvements.

The constraints preventing electric utilities from capturing the surplus paralleled railroads in important respects, and were also eventually imposed through regulation. Utilities charged volumetric rates for electricity consumed, not a share of manufacturing output. A factory paid based on kilowatt-hours used, whether it was producing innovative products or commodity goods. Regulation eventually standardized rate structures, limiting even the ability to price discriminate across customer classes. Utilities had minimal visibility into how electricity was being used productively—they knew aggregate consumption but couldn't observe which production processes were most valuable. And while some utilities did integrate forward into consumer appliances to stimulate residential demand, this was primarily about increasing electricity consumption rather than controlling downstream markets. Utilities faced prohibitive barriers to entering manufacturing directly; operating generating plants and distribution networks required different capabilities than running factories.

TelecomIn more recent memory, the telecom bust following the dot-com crash was severe. Several competitive local exchange carriers went bankrupt between 2000 and 2003. WorldCom filed for the largest corporate bankruptcy of its time in 2002. The resulting consolidation was substantial—Level 3 Communications acquired multiple bankrupt competitors' assets, Verizon absorbed MCI/WorldCom, AT&T was reconstituted through acquisitions. By the mid-2000s, broadband infrastructure was concentrated among a handful of major carriers.

But the fiber deployed in the 1990s—much of it still in use today—enabled the internet economy to flourish. The economic productivity gains from internet access are well-documented: e-commerce, SaaS businesses, remote work, streaming services, cloud computing, and so on.

The constraints limiting telecom value capture were similar to earlier cycles. Carriers primarily sold bandwidth based on monthly subscriptions or per-gigabyte charges, not revenue shares from application success. A startup building on fiber infrastructure paid the same rates as established businesses. Carriers had limited visibility into which applications were succeeding and could not easily observe application-layer innovation. And telecom providers faced substantial technical and regulatory barriers to competing at the application layer during the critical formation period. Network operators were not positioned to compete with e-commerce sites, SaaS platforms, or streaming services in the late 1990s through early 2010s when the web economy was taking shape.

There were exceptions that tested these boundaries. AT&T's acquisition of Time Warner and Verizon's forays into media ventures showed carriers trying vertical integration. And the important net neutrality debates centered on whether carriers could favor their own services or extract rents from application providers. Regardless, during the critical period when the web economy came into prominence, telecom companies were not vertically integrated and therefore their infrastructure was available on more horizontal terms.

The pattern across all three historical cases is consistent. Infrastructure consolidation happened and proved sticky, raising legitimate competition concerns. But structural constraints meant even monopolistic infrastructure owners could not fully capture application-layer surplus. They charged for access to infrastructure—shipping, kilowatt-hours, bandwidth—but the productivity gains from using that infrastructure diffused broadly through the economy. The long useful lives of the infrastructure meant these spillovers persisted for decades, even as ownership consolidated.

GenAI's Obsolescence TrapAs I've discussed here previously, the chips powering today's AI systems have useful lives of one to three years due to rapid technological obsolescence and physical wear from high-utilization AI workloads. This short useful life means that even if AI infrastructure spending produces excess capacity, that capacity will not be available for new entrants to acquire and leverage effectively. In railroads, electricity, and telecom, stranded assets with decades of remaining useful life became resources that others could access. Three-year-old GPUs do not provide a competitive foundation when incumbent coalitions are running current-generation hardware. Put differently, in a hypothetical 2027 GenAI bust, an over-leveraged data center stocked with 2-year-old H100s will be comparatively worthless. That compute cannot be bought for pennies on the dollar to fuel new competition. The only entities that can survive are those hyperscalers with the massive, continuous free cash flow to stay on the "GPU treadmill"—namely, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta. (Dramatic increases in software efficiency could break this hardware moat, but the hyperscalers control over distribution channels is difficult to overcome.)

The combination is what changes the outcome: vertical integration that enables surplus extraction, information position that enables direct competition, coalition structure that subordinates model developers to infrastructure owners, and short asset life that prevents the emergence of reusable infrastructure that others can access.

GenAI's Vertical Integration Overcomes Prior ConstraintsThe GenAI infrastructure buildout is producing market concentration through coalition structures: Microsoft-OpenAI, Amazon-Anthropic, Google-DeepMind. These are not loose partnerships—they are deeply integrated arrangements where the hyperscaler's infrastructure economics directly enable their coalition's competitive positioning at the application layer. Microsoft has invested billions in OpenAI and provides exclusive Azure infrastructure. Amazon is heavily invested in Anthropic. Google acquired DeepMind and is developing Gemini models that are integrated across Google Workspace and Cloud.

This vertical integration attacks all three constraints that limited value capture in past cycles.

First, usage-based GenAI pricing captures application-layer surplus through uncapped rates. Historically, railroads also charged based on usage—more cargo meant higher bills—but eventually regulators imposed the requirement to charge "reasonable and just" rates. Similarly, electric utilities charge per kilowatt-hour but face state commission oversight that caps rates at cost-plus-reasonable-return. These regulatory firewalls prevented infrastructure providers with natural monopoly characteristics from extracting surplus beyond what regulators deemed justified by their costs. While GenAI providers charge uniform per-token rates, they do have common carrier obligations. Moreover, while enterprise pricing remains opaque, the structure of published rates suggests that costs scale in close proportion to usage. This pricing structure, unconstrained by rate regulation or transparent volume pricing, allows concentrated infrastructure providers to capture ongoing application-layer surplus as successful applications scale.

This capability has implications beyond just who benefits. In past cycles, infrastructure owners couldn't capture application-layer surplus, which meant projected revenues never materialized and bubbles burst. If GenAI's rent extraction model works, it changes the financial calculus and hyperscalers may actually generate sufficient revenues to cover their capital expenditures. But this "success" would come at the cost of concentrating gains rather than diffusing them broadly.

Second, API usage patterns reveal application-layer innovation. Railroads could not easily observe crop profitability, utilities could not see manufacturing processes, and telecom providers in the 1990s-2000s could not easily monitor which web applications were succeeding. Hyperscalers can see which applications are working through API call patterns, token usage, and query types. This information asymmetry could allow them to identify promising use cases and compete directly. For example, Microsoft can observe what enterprises build with OpenAI. Or Google can see which applications gain traction on Gemini. The infrastructure position provides comprehensive competitive intelligence about the application layer.

Third, hyperscalers are positioned to compete at the application layer. Railroads did not enter farming, utilities did not run factories, and while some telecom providers in the 1990s tried to compete with web startups by using "walled gardens" that strategy failed. By contrast, hyperscalers are already application-layer competitors. Microsoft competes in enterprise software. Google competes in productivity tools through Workspace. They can leverage GenAI capabilities to enhance existing products while simultaneously selling API access to would-be competitors. The integration runs both directions—infrastructure enables their own applications while extracting value from others' applications. Indeed, in the software industry there is a long history of platforms cannibalizing or "sherlocking" the applications they enable.

Moreover, this dynamic differs fundamentally from how cloud services were used in the last decade. When Netflix or Uber ran on AWS, they used the cloud as a commodity utility to host their own proprietary code and business logic. Amazon provided the servers, but it was not the "brain" of the application. In the GenAI stack the application logic—the reasoning, the content generation, the analysis—resides within the infrastructure provider's model, not the customer's code. This shifts the relationship from hosting a business to "renting cognition," allowing the infrastructure owner to capture a significantly higher share of the value creation.

The coalition structure reinforces vertical control. OpenAI is the public face of AI innovation but is structurally dependent on Microsoft's infrastructure. Anthropic operates primarily on AWS and is tied to Amazon's ecosystem. Even the most prominent model developers lack true independence—they're subordinate partners in coalitions where the hyperscaler captures value through multiple channels while retaining the option to marginalize or compete with the model developer if advantageous.

Consolidation Without SpilloversIn past infrastructure cycles, the implicit social bargain was clear: while investors lost, society gained. Railroad, electricity, and telecom markets all concentrated substantially after their corrections, but the infrastructure continued enabling broad economic gains that owners could not fully capture. GenAI breaks this pattern. Whether through sustained profitability (enabled by rent extraction) or through post-bust consolidation (without reusable stranded assets), we may not get the historical consolation prize.

The primary counter-narrative rests with the open-weight ecosystem. A robust, competitive landscape of open models could directly challenge the structural constraints that enable surplus extraction. This open-model path, therefore, represents a critical mechanism for realizing the broad, decentralized "spillover" benefits that characterized past infrastructure cycles. Thus, supporting this ecosystem, whether through public access to compute or pro-competitive interoperability rules, should be a strategic imperative for ensuring that the productivity gains from AI diffuse broadly rather than concentrating within the hyperscaler coalitions.

Author Note: Thanks to Sander McComiskey for his excellent research assistance and critical feedback. Also thanks to Andrew Shi and Arvind Narayanan for invaluable feedback.

Mihir Kshirsagar directs Princeton CITP's technology policy clinic, where he focuses on how to shape a digital economy that serves the public interest. Drawing on his background as an antitrust and consumer protection litigator, his research examines the consumer impact of digital markets and explores how digital public infrastructure can be designed for public benefit.

The post Why the GenAI Infrastructure Boom May Break Historical Patterns appeared first on CITP Blog.

Pictured: Varun Satish (left); Jason Persaud (right)

Pictured: Varun Satish (left); Jason Persaud (right)

Varun Satish is a Ph.D. student in demography at Princeton University. His current projects include using language models to study the life course, and using machine learning to uncover shifting perceptions of social class in the United States over the last 50 years. Satish is originally from Western Sydney, Australia. Princeton undergraduate Jason Persaud '27 recently sat down with Satish to discuss his interdisciplinary interests, how sport inspires his work, and some advice for students.

Jason Persaud: Could you begin by telling us a little bit about yourself and some of the work that you do here at the CITP?

Varun Satish: Hello, my name is Varun. I'm a fourth-year Ph.D. student affiliated with CITP and the Office of Population Research. Some of my research that I've done here with people at CITP is about essentially taking large language models and using them to solve classic problems in the social sciences. So people generally use language models for things like text classification or summarization. What we're trying to do is take these models and use them for finding patterns in social data.

Jason: Could you talk a little bit more about some of those problems in that sociology sphere that you use language models to study?

Varun: A bunch of researchers essentially showed that life outcomes - for example, predicting someone's GPA at age 15 when given information about them at age 9 - is really hard to predict. There is a lot of social variation to life than we're trained to think, but we don't know what the sources of those unpredictabilities are. There are two ways to think about it. One of them is that there is fundamental unpredictability in the things we try to learn about. The other is that we haven't designed the right tools to actually predict these outcomes.

Because we don't really know about the sources of unpredictability, one thing we're trying to do is develop new approaches to prediction to see if we can do better. If using new approaches and using new data results in higher accuracy, it's an indication that maybe it's a vote for or against this hypothesis - that it's just fundamental variation in the data. And so what we've been trying to do, and what we have done, is use language models to do that.

We haven't yet shown that it's done better than the classic approaches - but the amount of time we've spent developing this approach compared to how much time has been spent developing the classic approaches is very different.

Jason: Okay, cool. On that note, could you tell us a little bit about some of the projects you're currently working on right now?

Varun: The project that I've worked on the most with people at CITP was developing this language model approach to predicting life outcomes. And this is a crazy story - but we participated in this challenge, which people familiar with Kaggle-style competitions might recognize; same evaluation metrics, same data - people competing to produce the most accurate model.

We participated in one of these using administrative data from the Netherlands to predict fertility. So, using data up to 2020, predicting whether people would have a child between 2021 and 2023.

What this entailed was going to the Netherlands for three months, and we developed this approach; our approach was essentially to take this complex administrative data, turn it into text summaries that we call "books of life," and then fine-tune a large language model to do this prediction of the outcome.

And we named the model after Johan Cruijff, an iconic Dutch footballer. Even this notion of taking the recipe and changing the ingredients is very much in line with Johannes Cruijff's total football - and his philosophy served as the backbone of our intellectual inspiration.

Satish speaking with Persaud at CITP in Sherrerd Hall

Satish speaking with Persaud at CITP in Sherrerd Hall

Jason: No, I think that's really cool. I like the inspiration - or I guess, the allusion to the soccer players. Okay, on a different note, you're from Australia, right? How has that shaped the questions that you ask or seek to answer in your research?

Varun: That is an interesting question. It has in ways that are maybe not as direct as you might think. I would say that coming from Australia, universities there are more fundamentally interdisciplinary because there's not as much money.

So my tastes and inclinations are obviously interdisciplinary because that's where I came from. There wasn't a sociology department at Sydney Uni or a demography department at Sydney. Places are far more where people from different perspectives come together to work on different things.

And so I think that's really impacted my work. But also, because I didn't go to university in the U.S., the types of questions that I find interesting are different because I just haven't been socialized to what's considered interesting here. So I naturally gravitate to places like CITP, for example, because that's where people like that are.

"I think a lot about how research feels creative to me, and creativity often stems from actually just letting go and letting it happen."

Jason: Obviously, you do a lot of research in terms of predicting outcomes based on data. What has been the most interesting relationship that you've studied?

Varun: This is completely separate work, actually. But one of my pieces of research is about trying to understand perceptions of class in the United States.

So if you ask people whether they're lower, working, middle, or upper class - what predicts that? What accounts for the variability in that? What I found is that over time, even though people are not worse off in material terms - they have the same amount of money - they're far more likely to identify as working class or lower class.

And this isn't something that's happened recently; it's the result of a longer process over 50 years. I don't think that means those people are wrong. What's actually been happening is that people with college degrees have much higher incomes.

So what's happening is that, to me, we have these stories about inequality in the U.S., but what I found using predictive models is that you can actually see how it's shaping people's perceptions in the data.

As people at the higher end of the attainment hierarchy earn more and more money, people who aren't at that higher end - even though they're not classically considered "worse off" - still feel the effects of the shifting income distribution.

Jason: Lastly, what advice would you give to undergrad students who are interested in the work that you're doing right now?

Varun: As someone who studies predictability, what I've learned is that most things are unpredictable. And so you should just relax. If you're an undergrad: things will work out in ways that you don't realize, and your path will be very winding. I think a lot about how research feels creative to me, and creativity often stems from actually just letting go and letting it happen. And that is very anxiety-inducing, but that is the work.

Most people who are reading this are probably Princeton undergrads - you're fine. You're very capable, and you'll figure it out.

Jason Persaud is a Princeton University junior majoring in Operations Research & Financial Engineering (ORFE), pursuing minors in Finance and Machine Learning & Statistics. He works at the Center for Information Technology Policy as a Student Associate. Jason helped launch the Meet the Researcher series at CITP in the spring of 2025.

The post Meet the Researcher: Varun Satish appeared first on CITP Blog.

*The deadline has been updated to December 8, 2025 as of November 13, 2025.

Applications are now open for Princeton University's Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) 2026-27 Fellows Program. Candidates are encouraged to apply by the start-of-review date of December 8*, 2025. The applications are open now (links are available below according to track) and applicants may apply for more than one track. The Center is seeking candidates for the following three Fellows tracks:

- Postdoctoral Research Associate (1 - 2 years) - see a list of advisors below.

- Visiting Research Scholar (Visiting Professional) (1 academic year)

- Microsoft Visiting Research Scholar (Visiting Professor) (1 academic year)

What is CITP?

The Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) is a cross-disciplinary center of researchers whose expertise in technology, engineering, public policy, and the social sciences focuses on the relationship between developing technologies and its implications in our society. CITP's research falls into the following three areas:

- Platforms and digital infrastructure

- Data science, AI and society

- Privacy and security

What is the Fellows Program at CITP?

The Fellows Program is a competitive, fully-funded, in-person program located in Princeton, New Jersey, that supports scholars and practitioners in research and policy work tied to the Center's mission. Fellows accepted into this program conduct research with members of the Center's community — including faculty, scholars, students, and other fellows — across disciplines, and engage in our public programs, such as workshops, seminars, and conferences.

Both CITP and Princeton University place high value on in-person collaborations and interactions. As such, candidates are expected to participate in-person at CITP on the Princeton University campus in Princeton, New Jersey.

Postdoctoral Research Associate Track - List of AdvisorsThe postdoctoral track is for people who have recently received or are about to receive a Ph.D. or doctorate degree, and work on understanding and improving the relationship between technology and society. Selected candidates will be appointed at the postdoctoral research associate or more senior research rank. These are typically 12-month appointments, commencing on or about September 1, and can be renewed for a second year, contingent on performance and funding. Fellows in the postdoctoral track have the option of teaching, subject to sufficient course enrollments and the approval of the Dean of the Faculty.

Most postdocs are matched to a specific faculty adviser. A list of CITP Associated Faculty and the areas in which they are looking for postdocs are as follows (more topics / advisers may be added):

- Professor Molly Crockett: (1) Ethical and epistemic risks of AI, (2) AI and diversity in scientific research and (3) sociotechnical approaches to AI value alignment.

- Professor Peter Henderson: Seeking candidates interested in reinforcement learning and language models for strategic decision-making, exploration, and public good.

- Professor Manoel Horta Ribeiro: Interested in candidates with experience in data science, AI, and society.

- Professor Aleksandra Korolova: Interested in candidates for a joint appointment with other faculty (see joint topics below) with experience in the following: digital infrastructure and platforms; privacy and security.

- Professors Lydia Liu, Matthew Salganik and Aleksandra Korolova (Jointly): 1.) Evaluation of AI models under data access constraints with connection to legal compliance (EU, NYC local law), algorithmic collusion. 2.) Bridging predictions and decisions, especially through a simultaneous/multiple downstream decision-maker lens.

- Professor Jonathan Mayer: please look at Professor Mayer's website for research interests.

- Professor Prateek Mittal: Interested in candidates with a background in 1.) Network security and privacy (e.g., enhancing the security of our public key infrastructure) and 2.) AI security and privacy.

- Professor Andrés Monroy-Hernández: Interested in candidates with background in AI and labor to contribute to the Workers' Algorithm Observatory.