The latest album from UK ensemble Hen Ogledd is a striking invocation of the mythic and mundane, writes Abi Bliss in The Wire 505

Hen Ogledd

Discombobulated

Domino CD/DL/LP

One of the more unexpected musical evolutions in recent years has been that of Hen Ogledd from the group's origins as a side project for harpist Rhodri Davies and singer-guitarist Richard Dawson. The knotty, writhing improvisations of the pair's 2013 album Dawson-Davies: Hen Ogledd were like wrestling a piglet in a barbed wire jacket, but with the addition of multi-instrumentalists Dawn Bothwell and Sally Pilkington, by the time of 2018's Mogic, Hen Ogledd had become a bold, poppy but still defiantly experimental quartet. With Dawson now on bass, Davies's electrified strings remained a bubbling, gravelly sonic wellspring around which their musical horizons expanded.

Veering between crisply crafted songs such as "Problem Child" and looser-limbed jams, with lyrics tackling human connection in the digital age, Mogic was inspired but scrappy, as colourfully creative yet jokily deflecting as the appliqué capes each member sported in its videos. If anything, its 2020 sequel Free Humans was too consistent, leaning heavily on neon electropop to tackle the frailties of the heart across a timespan ranging from medieval gossip to future space exploration. But with Discombobulated, Hen Ogledd have grown to fully inhabit their costumes, Sun Ra Arkestra style, with the greatest musical and lyrical realisation yet of their diverse strengths.

Hen Ogledd is Welsh for Old North, and refers to an early medieval region spanning the north of Wales, northern England and southern Scotland. At the fringes of Roman influence and where Brythonic languages - forebears of Welsh, Cornish and Breton - were spoken, the area includes the birthplaces of all four members, highlighting a kinship between parts of the UK often overlooked in Londoncentric narratives. Invoking both the mythic and the mundane, Discombobulated draws upon landscape, folklore, popular dissent and individual struggles, enriched by major contributions from saxophonist Faye MacCalman and trumpeter Nate Wooley, and by passing appearances (ranging from vocal non sequiturs to field recordings) from numerous friends and family members.

After one child recounts a dreamlike vignette of sound-collecting fishermen on opener "Nell's Prologue", "Scales Will Fall" raises the protest flag, its call for youth to overturn the institutions of corporate greed delivered in emphatic spoken word by Bothwell, rousingly backed with brassy synth lines, Will Guthrie's economical yet persuasive drumming and a massed chorus singing "The fire in your soul is only fool's gold". The rallying procession is tempered by a melancholy that finds voice in Wooley's lyrical solo, with a world-weary majesty that wouldn't be out of place on Super Furry Animals' downbeat 2000 masterpiece Mwng. Similarly, the Davies-sung "Dead In A Post-Truth World" addresses the far right voices that the BBC's Newsnight programme is all too fond of platforming - "Mae gamwn ar y teledu/Mae'n amser mynd i'r gwely" ("When gammon is on the TV/It's time to go to bed") - its fragmented harmonies, wah-wah harp, twisting sax and fidgeting snares providing a counterpoint of complexity to easy answers.

Elsewhere, the natural world is a place of both wonder and loss. Framed by watery organ chords and what might be a rattling film projector, "Clara" starts with Bothwell's lilting lullaby of horseriding but stumbles into degraded, polluted landscapes. Davies and his children sing "Land Of The Dead", a Welsh translation of an enigmatic Dawson lyric in which the veils between nighttime countryside and eldritch realms dissolve more with each verse.

Time itself rejects a linear path in "Amser A Ddengys" ("Time Will Tell"), the line "Dyna oedd ddoe a dyma yw heddiw" ("That was yesterday and this is today") delivered simultaneously with the song's other three lines by an a cappella choir of Davies. And in "Clear Pools", the cycles signify rebirth and renewal, as initial chaos gives way to clean harp chords, MacCalman's warm, nurturing tones and soft, enveloping textures that wax and wane around the vocals over nearly 20 minutes. But a hot disco can be as transcendent as a cold pond, and the driving "End Of The Rhythm" best encapsulates the album's mood of battered but persisting hope, trumpet, harp and sax lines all yearning for a better tomorrow as Pilkington celebrates "A dancing, contagion/Releasing, rampaging/Our bodies, in union/Spontaneous, communion".

This review appears in The Wire 505 along with many other reviews of new and recent records, books, films, festivals and more. To read them all, pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Wire subscribers can also read the issue in our online magazine library.

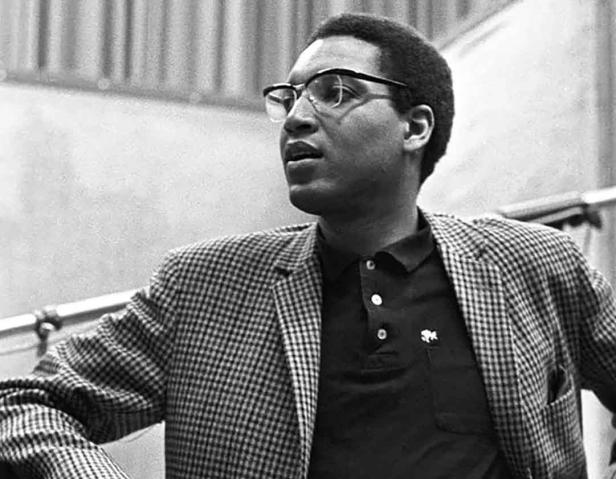

In the introduction to her collection of writings on Tom Wilson, Anaïs Ngbanzo gives an overview of the influential producer's life

It was December 2004 and I was watching Bob Dylan get into heated conversations with journalists during his 1965 British tour in Dont Look Back. Halfway through DA Pennebaker's film, when Dylan sits at the piano and starts playing an early version of "I'll Keep It With Mine", the camera lingers on a man seated next to him, eyes closed, deeply listening. This was the first time I saw Tom Wilson. Over the following years it occurred to me that the photographs of Dylan's 1965 recording sessions, and those of Nico promoting Chelsea Girl at ABC studios, and the one of Frank Zappa standing in a bright studio during the recording of We're Only In It For The Money have one thing in common: Wilson is there. I started researching Wilson.

Thomas Blanchard Wilson, Jr was born in 1931. He grew up in Waco, Texas with a librarian mother and a father in the insurance business. He attended Moore High School, where he played saxophone in the school band. He later played trombone and took cello classes for a couple of years - the only formal musical training he ever had. His music-related childhood memories would involve his father conducting a choir at the Texas state centennial celebrations of 1936 and the jam sessions held on Saturday afternoons at his grandfather's carpet cleaning business. A year after enrolling at Fisk University in Nashville he had to take two years out getting tuberculosis treatment, but then, in 1951, he went further north to study economics at Harvard.

In Cambridge, Wilson became committed to university radio station WHRB - broadcasting classical and popular recordings. He later said: "I owe everything accomplished in the recording field to highly informal but inspirational training as a member of WHRB." The Harvard archives also show his membership in its most active political club: the Young Republicans. "For some, being a Young Republican was a full-time job, an exercise in wardheeling," explained an alumni report. "For others, the club was an easy-going, semi-social organisation, which provided interesting speakers and dances."

In early 1953, Wilson founded the Harvard New Jazz Society. The club was to create "an atmosphere here at Harvard that will foster an appreciation of the idiom," as he told the Harvard Crimson, extending an invitation to "all interested in jazz and its recognition as an indigenous art form." With its informal performance and lectures, the New Jazz Society received national publicity and established jazz among the more entrenched musical forms at Harvard. Wilson graduated in May 1954.

That summer he took a job at the Stop & Shop supermarket chain as assistant buyer, languishing at its South Boston headquarters for a few months. Although only 24 years old, he already had strong connections with gifted musicians of the Boston area jazz scenes and a plan to record them. In a 1956 interview for Metronome, Wilson recalled sitting in a friend's living room talking about trends in music when he said, "If I had a thousand dollars I'd prove something." The girlfriend (as yet unidentified) of fellow Harvard graduate Charles Henri La Munière, having command of an annuity, offered Wilson $940 that day to start cutting records. As a result he started his label Transition Records in Cambridge in March 1955. That same year he married Beverly J King; they would welcome their first child, Thomas Blanchard III, in 1956.

Herb Pomeroy's Jazz In A Stable is the first Transition record, and Donald Byrd was the first artist to be signed. Recordings were made in various locations - and through his lasting relationship with the university, Wilson was able to use WHRB's engineering staff and a completely renovated studio there known as "studio B." With the assistance of Harvard students and alumni A Ledyard Smith, Stephen A Greyser, Edward H Rathbun and Dean Gitter, Transition swiftly came to prominence in jazz recordings - collaborating with John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, and Cecil Taylor. Yet it continued to operate from Wilson's living room and it was losing money: Wilson had to moonlight as membership secretary in the Waltham Boys' Club during 1957-58 to make ends meet. Transition Records folded in the summer of 1958. The Wilson family moved to New York shortly after the birth of their second child, Darien Wilson, that September.

Upon arrival in the city, Wilson started a career in A&R (artists and repertoire) for indie and major labels, taking a job at United Artists until February 1960. Later that year he founded Communicating Arts Corporation, which produced jazz radio programmes on the New York metropolitan area classical station WNCN-FM, while doubling as jazz A&R director at Savoy Records and as executive assistant to Malcolm E Peabody, Jr, director of the New York State Commission for Human Rights. In 1962 he joined Audio Fidelity Records as associate recording director.

A pivotal encounter occurred in mid 1962: Goddard Lieberson, a former A&R man now heading CBS-Columbia Group, heard Wilson speak before a meeting of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Lieberson, under whose leadership the CBS music division had become the world's leading recording company, was impressed enough to hire him on the spot. Wilson's role as staff producer at Columbia from 1963 to 1965 would be a significant moment of his career - getting press attention as "the man who produced some of Dylan's hits" and who made a success out of Simon & Garfunkel's "Sound Of Silence."

In November 1965 he joined MGM Records as East Coast recording director, recording The Animals and signing The Velvet Underground, Nico, and The Mothers Of Invention. The vice president of the label, a Wilson admirer, entrusted him with a radio interview program called The Music Factory, sponsored by Verve/MGM and syndicated to college stations across the country.

This was the last role Wilson took at a record company before creating the Wilson Organisation in 1968 with a handful of partners, leasing its services to Motown Records. Subsidiary firms included Terrible Tunes and Maudlin Melodies (publishing), Reluctant Management (talent direction), and Rasputin, Gunga Din, and Lamumba Productions (independent recording production). "You know why I went independent?" he told writer Ann Geracimos in 1968 for a New York Times cover story. "Because I got tired of making money for a millionaire who didn't even bother to send me a Christmas card. I discovered if you are honest, you get a lot further. A guy's not going to respect you if you don't fight for what you think you are worth.

In 1976 Wilson told writer Michael Watts for Melody Maker that he and his business partner Larry Fallon had written a rhythm and blues opera, Mind Flyers Of Gondwana, that wove together Plato's allegory of Atlantis with African American history. The idea was that Johnny Nash would play the lead; other names mentioned were Gladys Knight (as a queen), Labelle, Gil Scott-Heron, Melba Moore and Minnie Riperton. The Righteous Brothers were to play Mason and Dixon, and it was hoped that Bob Marley would record a reggae soundtrack. They were trying to get Stanley Kubrick interested in a film version. But the project never saw the light. Wilson, who had a history of heart trouble, died at home in Los Angeles, California on 6 September 1978. He was 47 years old.

Working on this book, the first devoted to Wilson, I wondered what he would have made of it. Geracimos writes in her article, "A Record Producer Is A Psychoanalyst With Rhythm", that:

"Although extreme frankness is one of his strong characteristics, he is reluctant to talk about some of his extra-curricular activities (any drug-taking experiences, for example), because of what people back in Waco might think. 'Just don't say anything that might hurt my family,' he says. [...] The pressures of the profession evidently lead him to seek diversion in a number of unorthodox ways. Rock 'n' roll music, of course, is not all sound. It refers to a certain style as well, which Wilson, in trying to court extremes and the happy middle simultaneously, represents perfectly. The public side of Wilson is responsible and pragmatic."

This is an edited extract from the introduction of Everybody's Head Is Open To Sound: Writings On Tom Wilson, edited by Anaïs Ngbanzo and published by Éditions 1989.

You can read Francis Gooding's review of the book in The Wire 505. Pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Subscribers can also read the review and the entire issue online via the digital library.

Music can act on listeners in ways that Western modes of engagement and criticism overlook or erase, argues Moravian composer and vocalist Julia Úlehla in The Wire 505

I've just given a keynote presentation at Lines of Flight: Improvisation, Hope and Refuge, a conference hosted by the International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation. I'd been invited to talk about my performance research with Dálava, a cross-genre project that is influenced by animist, Slavic cosmology and a land-based folk song tradition that has been in my family for generations. After the presentation a woman approaches me. "There's something I need to tell you. A spirit entered my body while you were singing and has a message for you." She delivers the message and hugs me warmly. Once delivered, her demeanour transforms, as if a weight lifts. She promptly and politely says goodbye.

As this encounter suggests, singing is a devotional practice for me, one that connects me to my ancestors and other spirits, and affords an animist experience of reality. Music born of traditional and spiritual practice is increasingly visible in experimental and underground circles. But music of this kind is often at odds with the patriarchal colonial bias that constrains how music is written about and studied. Listeners, practitioners, teachers and writers need to find ways to move beyond this bias and avoid the harms of misrecognition, desacralisation, instrumentalisation, commodification and extraction.

The musical history of Canada, the nation state in which I live, is built on the extraction of Indigenous song and culture and erasure of Indigenous peoples and lifeways. In current music writing about artists who are women and people of colour, exotification, mischaracterisation and assumptions based on gender, race and ethnicity are common. In a letter in The Wire 424 in which she corrected inaccuracies arising from false assumptions based on her ethnic and racial identity, Amirtha Kidambi notes, "this kind of mischaracterisation and looseness with facts is much more common in stories about women and people of colour... we rarely get to dictate even the facts of our own stories, in the way many of our white male colleagues do, and are narrativised time and time again, in inaccurate and uncomfortable ways…"

Throughout my career I've seen women, queer, trans and racialised colleagues who work with voice prefer to situate themselves inside movement, dance, theatre or performance art milieus because of the patriarchal, colonial bias in music. During my PhD in ethnomusicology, I researched folk songs from Slovácko, a rural region at the western edge of the Carpathian mountains. In this tradition - which has been sung by generations of my family members - ancestor and other spirits, mountains, rivers, wind, weather, humans, animals and plants are understood as agentive, alive and interrelated. My advisor told me to keep my body, my family and my creative practice out of my research, adding that I should maintain a scholarly distance and satisfy his appetite for facts. He asked me to take spirit out of my writing, warning that it would unpalatable for colleagues.

These statements suggest that knowledge cannot arise in the body, and that one's family lineages and exploratory musical practices are not viable fields for research. Gatekeepers have appetites that can only be satisfied by facts obtained through the perceptions of an unaffected, distant observer. Spirits are the stuff of an (often feminised or racialised) Other's belief, fantasy or psychosis. To present them as part of a valid epistemological and ontological field invites ridicule.

I'll give a few examples of what people thinking outside this dominant ideology have told me that they perceive when listening. Neither platitudes nor praise, these comments open imaginative space for what language about music is, or could be. The encounters they describe bridge across alterity without collapsing difference, foregrounding embodied experience, spiritual encounter and collaborative wondering. These exchanges include modes of listening and giving language to musical experience that avoid reification and instead open towards relationship.

A young woman came up to me after a performance and told me that she "grew up inside a Hindu household where music, devotion and the domestic were inextricably linked". She continued, "The performance felt like being home. Your music lives in the heart. Depending on the relationship a person has to their own heart influences how they will hear you."

What if the way we respond to music has more to do with emotional flows and blockages than aesthetic preferences? What would happen if we knew we might be having our hearts worked on when we listened to music, or conversely, when we performed for someone, we might be engaging with their hearts? What does that do to accountability? Would we consent to that? What are we turning away from if we never think about it?

A Syilx woman told me that she palpably felt and saw the land that the folk songs I sing come from and was moved by how beautiful the land was. What if certain songs are inseparable from the lands they grew from, as though the songs themselves contained the land, or could bring the spirit of the land to them? In this diasporic world, what are we asking genus loci to do when we bring them across the world? What are the consequences when songs from faraway lands appear upon stolen, occupied, Indigenous land, and how is each context different? Are we, for example, introducing lands or ancestors to one another in generative ways? Who determines that? Or enacting another form of settler colonialism in the spirit world?

A Serbian woman told me that the performance allowed her to experience "the existential liberation of Slavic melancholy". She said, "If you travel down to the very bottom of suffering, on the other side lies freedom." What if songs are medicine, capable of bringing healing to suffering? What if we knew that when we gather to listen to music or perform for others, we could travel to the bottom of suffering and pass through it together?

And as the opening story reveals, song is a powerful way of communing with ancestors and other spirits. What if we went to concerts knowing that our ancestors were gathered in the room with us? What might we want to do together? Do we have issues to heal or celebrate within our lineages, or among those gathered? Do we know how to do this safely and responsibly, and are we all at equal risk?

These exchanges centre ways of knowing and listening that many academicised modes of engagement find hard to tolerate. Yet, many of us have had experiences like these through music; many of us long for them. Music helps us learn how to love, how to honour the land that sustains us, how to heal, how to grieve, how to visit with the dead, how to experience hierophany. No one is authority in these layered entanglements - not the musicians, not the audience, not the unseen. These relational encounters invite everyone to participate but don't work according to logics of control or distance. You have to let yourself be taken by something bigger. Can music criticism disarm itself enough to make space for this?

Julia Úlehla is a Moravian composer and vocalist. This essay appears in The Wire 505.

Pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Wire subscribers can also read the essay in our online magazine library.

As AI use spreads further into the creative industries, platforms like Bandcamp must be bold in their efforts to sort the good faith from the bad, argues Erick Bradshaw

Since its founding in 2008, Bandcamp has become an invaluable resource for musicians, from bedroom producers to pop stars, as a host for the streaming and buying of their work. With artists and labels selling a wide range of physical products in addition to every major digital format, Bandcamp is the closest thing to a globe-spanning independent record store. In 2022, founder Ethan Diamond sold Bandcamp to Epic Games, who then sold it to music licensing company Songtradr the following year. Despite these corporate turnovers, the site has not changed much: the Covid-era artist-benefiting Bandcamp Fridays still occur regularly and editorial wing Bandcamp Daily publishes new features, lists and scene guides every weekday. (Full disclosure: I am a Bandcamp Daily contributor.)

While it may be a closed environment, these elements contribute to a healthy ecosystem for artists and fans alike. When fraudulent goods are introduced, it is tantamount to an attack on the entire business model, a threat to the wellbeing of the marketplace. Such doubt becomes a poison, a virus. AI-generated music is that poison. Spotify has been plagued by an influx of AI-generated music that is streamed by bot farms to generate royalties for the perpetrator. This act of "polluting the algorithm" degrades the experience for everyone and funnels money away from where it is most needed.

In a post published on 13 January, entitled "Keeping Bandcamp Human", the company stated that "musicians are more than mere producers of sound. They are vital members of our communities, our culture, and our social fabric. Bandcamp was built to connect artists and their fans, and to make it easy for fans to support artists equitably so that they can keep making music." This was the argument at the centre of the platform's decision to prohibit music generated wholly or in substantial part by AI, which has been met with some resistance by those for whom AI is an integral part of their practice.

Process music, systems music, cybernetic music, player pianos, samplers, emulators, AutoTune, advanced software plug-ins - algorithms have been part of music creation for decades. Parameters are established, instructions are given and music is produced. But imagine doing that on a near-infinite basis and seeding it through every platform on the planet, like a digital kudzu vine. "Make any song you can imagine" promises the company motto of AI-powered music generation platform Suno. At what point did we decide that music made, or at the very least, shaped by humans was not enough?

There are tried and tested ways of making songs in real time without the need for AI. Songs, especially those written by bands or collaborations between individuals, are formed in the heat of the moment, through jamming or working on variations of a theme as a song is hammered into place. This is also true with electronic instruments: sometimes the twist of a knob can radically alter the trajectory of a song. Free improv, the most blatantly "organic" music, is almost completely based upon these principles. The physical space, the smell in the room, the hand slipping from sweat - all of these things make the music live in the present, sound waves moving through the air at that particular moment. Why waste your time creating something, spending time working on it, making mistakes, learning from those mistakes, using those mistakes, turning the mistake into the essence of the work itself, if you can rely on the likes of Suno? Unless, of course, you are invested in the messy business of being a human.

Parsing the meaning and intent from AI proselytizers can be difficult, but, much like the software systems themselves, they use this to their advantage. This is why making a straightforward counterargument is sometimes the best thing to do: just cut through the bullshit. Is it worth the ravaging of our physical world and psychic landscape to satisfy the tech classes' lust for co-opting the imaginations of their customers? It's a perverse bargain, and the only people who benefit are a tiny cabal of so-called angel investors. It may seem grandiose to say that the "training" of LLMs over the last decade amounts to nothing less than the intellectual theft of the entire human race, but why not lay it out in such explicit terms?

The use of generative AI in the arts is a hammer in search of a nail. Does the songwriting industry need to be "disrupted"? Do people need to write songs in the style of Max Martin, Linda Perry or Jack Antonoff? At some point, a vibe coder will hit Send on a prompt that will contain references, perhaps even finely-tuned preferences, to emulate The Shaggs, US Maple, Arthur Doyle, Yoko Ono or Ghédalia Tazartès. The question remains: Why? It doesn't negate the inherent value of the thing, but it does open up Pandora's box, and lets the curses stream forth.

It is possible to be sympathetic to forms of generative art and still decry their effect on the creative ecosystem. Generative AI's ability to create infinite reproductions of material fuels the transformation of art into content, and while some may quibble that generative AI features already exist in music making, for instance in software plug-ins, surely it's necessary to draw a line in the sand, even if that line risks excluding the few instances of genuinely creative uses of AI.

Will errors be made in the scrubbing of AI-generated music from Bandcamp? Most likely, but this is an e-commerce site, not air traffic control or heart surgery. Moreover, this music will continue to exist, whether on YouTube or Spotify, platforms that have long shed any pretence of prioritising artists over profit. Bandcamp must protect itself from chicanery.

In the first essay of a short series exploring Bandcamp's ban on AI-generated music, Vicki Bennett argues that the platform's decision rests on the belief in a stable binary between computer and human made music

On 13 January 2026, Bandcamp published "Keeping Bandcamp Human", declaring that "music and audio that is generated wholly or in substantial part by AI is not permitted on Bandcamp", alongside a strict prohibition on AI-enabled impersonation of other artists or styles. The post invites users to report releases that appear to rely heavily on generative tools, and it explicitly reserves the right to remove music "on suspicion of being AI-generated".

It frames the stakes in language that is hard to argue with: music as "human cultural dialogue", musicians as "vital members of our communities… our culture… our social fabric". The intention reads as protective: a platform built on direct artist support resisting an industrial shift in which generative systems turn music into an infinitely scalable by-product.

But the policy hinges on a category that cannot sit still: "AI music."

"AI" currently operates as a single alarm word for a sprawling range of tools, techniques, and infrastructures. Bandcamp's policy phrase - "wholly or in substantial part" - leans on exactly this flattening, implying a measurable cut-off point. Yet contemporary music-making already runs through predictive and algorithmic processes - pitch correction, time-stretching, transient detection, beat mapping, generative "assist" features buried inside plug-ins, to name a few. Some of these are marketed as AI today; many will become ordinary defaults tomorrow.

The result is a verification fantasy: the belief that a stable binary can be policed in sound; that an audible threshold exists for "synthetic" or "other". It promises certainty at a moment where certainty is eroding elsewhere too - images, voices, provenance, identity, authorship. It also underestimates how frequently practice collaborates with systems: tools, interfaces, archives, defaults and so on. Music reaches listeners through networks before it reaches them through ears, and those networks are already doing editorial work.

Bandcamp's policy is responding to a genuine structural threat: volume. Automated production changes the ratio of noise to signal. An already difficult discovery environment gets overwhelmed. Public hostility toward what is surfacing in feeds sits inside this dynamic, and it is understandable. Yet what most people encounter as "AI aesthetics" arrives pre-edited, boosted by ranking systems and controversy. The fear is real; the surface it attaches to is already curated. Bandcamp is trying to resist becoming a landfill.

The popular caricature of generative music imagines a one-way transaction: input a prompt, receive a track, publish it. That behaviour exists, and it has consequences. Yet another relationship exists too: immersive, dialogic use where the system becomes a site for discovery rather than a shortcut to a predetermined end. Bandcamp's policy language does not distinguish between these modes; it relies on a broad label and a suspicion threshold.

Generative music has existed for a long time - and not only in the contemporary sense of "model output." Long before large-scale machine learning, artists worked with systems that generate: rule-based procedures, chance operations, constrained scores, stochastic logics, feedback structures, and mechanical or computer-assisted processes. "Generation" reads as a recurring method for distributing agency across humans, tools, rules, and time.

Conlon Nancarrow's Studies For Player Piano are canonical precisely because they make a non-human musical capacity audible: tempo ratios and so on that bodies cannot reliably execute held in place by a mechanised system that does not "interpret". In White-Smith Music Publishing Co v Apollo Co (1908), the US Supreme Court held that music rolls for player piano were not "copies" of sheet music under the law at the time, in part because they were not intelligible to humans as notation. The ruling was later superseded, yet the impulse is instructive: authorship gets tethered to human legibility until technology breaks the tether. This is where the AI debate loses grip. It assumes automation erases authorship.

The more useful question is simpler: what is the role of the author under these conditions? Authorship cannot be considered merely writing, composing, playing any more: the actual practice of making shifts toward interaction, recombination, and editorial agency. The author's presence shows up in how a system is framed and interfered with: what is fed in, what is refused, and so on. In that sense, authorship becomes legible through constraint design and editorial decision making.

Moreover, the "humanity" of the author does not disappear when sound is synthesised or interfered with. It is disclosed through the interference itself: through the deliberate destabilising of sources, the creation of density, the building of "audio mulch" where recognition becomes unstable. That compositional stance sits uneasily with a suspicion-based regime that treats ambiguity as evidence. A policy that encourages judgement-by-vibe pushes complex work towards safer surfaces.

So, what is done with what is present, and with what consequences? A genuine public need exists - protection from impersonation and spam - and Bandcamp's prohibition on impersonation speaks directly to that need. But the broader prohibition targets a moving label and risks producing an optics economy where surface signals are designed to avoid suspicion.

Likewise, the discourse around exploitation needs refinement. Artists are being scraped and stolen from; this is real. But the temptation is to treat it as unprecedented and to call the entire field "the same". What about sampling and collage, which have lived inside those tensions for a long time? A platform policy anchored to a broad label cannot resolve that deeper political economy, and it may distract from where power is actually concentrating. So the question returns, sharpened: who benefits when the category "AI music" becomes the organising principle?

Bandcamp's cultural value has never been limited to commerce. For many, it is still the only workable route for sales and finding the appropriate networks. It functions as an informal archive of tags, micro-genres, and unclassifiable edges: the long tunnel of browsing, the rooms inside rooms, the productive disorientation of finding something you didn't know existed. A suspicion-driven policy makes that ecology more fragile by treating complex processes as a moderation problem rather than as a musical method.

The current moment is already a collision point: economic decisions, artistic freedom, quality, taste, and infrastructural control pressing into the same narrow space. Bandcamp's attempt makes that collision visible. The next step requires definitions that track behaviour rather than vibes, and governance that can resist flooding without shrinking the field of permissible experimentation. Otherwise, the platform preserves "human creativity" as a slogan while narrowing the conditions under which complex, process-driven work can survive.

Tool use will evolve fast. Model output will be run through "human filters"; many artists will train models on their own archives, treating the model as an extension of an already established editing practice. Authorship will not disappear in these workflows. It will become harder to locate through surface cues, and more important to understand through process. The responsibility now is to keep editing, with our eyes and ears wide open.

Philip Brophy analyses Colin Stetson's use of the saxophone's physical dimensions to evoke the disturbed voices and bodies of Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022) and Hereditary (2018)

As with all post-2010 franchise reboots, Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022) spins itself dizzy with reflexive stylistics, revisionist story lines and ideological closure. Musician and composer Colin Stetson's distinctly live improvisations of acoustic and processed brass and woodwinds are exploited for sensational affect. When Leatherface first dons his freshly dead mother's peeled face, Stetson deploys a growl deep from the bowl of what sounds like his baritone sax ("Sunflowers", the opening track on the LP release).

Part death metal aping, part psychotic impression, it highlights a key aspect of all monster figurations: the sound of their voice. Much of Stetson's cues for Texas Chainsaw Massacre combine vague vocal tones with breathy sustains, each overlaid with overtones and submerged in reverberant fog. In violent outbursts like "Sledgehammer", the score feels cognisant of Tobe Hooper and Wayne Bell's 'meat industry metalzak' for the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Stetson carves, sculpts and moulds his compound acoustics with greater turmoil.

Stetson thematically has directed his instrumental performances across the well known New History Warfare volumes (2007, 2011, 2013). He needn't have pointed out these pieces are recorded live and unedited: they throb with his circular breathing, muscular lungs, and immersion in the swirling sonorum he expels from his mouth. In an unlikely musical merger of Philip Glass arpeggios, 'acoustic acid' pulsations and inchoate metal vocalisations, the trilogy swells with a surprisingly emotional undertow. Like much of Stetson's work, New History Warfare is emotionally hot and performatively anguished. Most 'dark industrial' work in this terrain I find highly affected and closer to cabaret than anything else, but Stetson's grounding in the visceral dynamics of his physical instrumentation colours his compositions and recordings with convincing appeal.

I wonder how many filmmakers have temped their films during editing with tracks by Colin Stetson? His records supply emotional outbursts of debilitating affect which many a director might seek as an appropriate tenor for their hand-wringing tales of woe (a trope too many horror and sci-fi movies embrace). And here's the rub: Stetson's music alone conjures these ecstatic states of demolition and destitution, but when combined with visuals intent on evoking identical feelings in a viewing audience, the resulting audiovision can become overbearing, muddled and unintentionally caricatured.

I wonder how many directors realised this, and resolved to pull back the soundtrack to soften its bombast? The contrast between experiencing Stetson's score in the Texas Chainsaw Massacre and auditing it in isolation on record is stark. This is a generalisation, but the more sonically adventurous a score, the more likely a movie tends to limit its organic energy, as if the music is an untamed entity to be collared. The LP is like a portrait of Leatherface: traumatised, trapped and taunted as if caged in a hellish unending franchise of horror replications.

Three other Stetson scores perform identically: Color Out Of Space (2019), Uzumaki (2024) and Hold Your Breath (2024). Their music alone conveys far more than their accompanying films. Hold Your Breath is an especially lost chance to highlight Stetson's voice, considering it focuses on a Creepy Pasta-style 'Grey Man' whose lore has psychologically infected a woman and daughter struggling to keep their Dust Bowl ranch going during the 1930s climate devastation. The film abounds with some great sound design and voice editing which foregrounds the palpable psychoacoustics of diseased lungs and vocal deterioration. But Stetson's metallic human tones and breathy granularity are plastered almost indiscriminately, like the showy CGI dirt storm clouds and artsy defocused cinematography.

To play devil's advocate: is the problem that Stetson's emotionally 'hot' music is a liability due to his inability to rein it in and properly service the film's narrative? Man, that's such a conservative view, which cinema continually upholds. A director not the composer is the one tasked with resolving and incorporating such intense energies (visually, performatively, sonically); they can experiment with pushing things or choose to pull back. Stetson's first major score commission for Ari Aster's Hereditary (2018) clarifies the benefits in perceptively handling powerful music like Stetson's within a film's narrative world.

Hereditary is as showy with its aesthetic gambles as the other films mentioned here. The opening camera creep into a model of a family house raises a reference flag to Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980), whose overhead camera tracks Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) roaming the snowed-in hedge maze: the optics are of an animatronic doll in a diorama. His positioning throughout the film had repeatedly alluded to his withering self being a figurine sinking into a dimension governed by ghostly usurpation. Hereditary's story layers this theme onto the dysfunctional family's teenage son, Peter (Alex Wolff). But relevant here is how Stetson's music accompanies that dollhouse opening. A spindly melody from his bass clarinet symbolically traces the claustrophobic contours of the dollhouse bedroom.

Something else floats in the background here and elsewhere in the film: distant harmonics, resonant notes and whirring altissomo squeaks, like chamber music being played in the distance. This vague wallpaper of domesticity - classical, mannered, cultured - is not film music in the normative sense. Rather, it scores how music indifferently occupies familial space, simultaneously placating and irritating a family group (convened with frailty by artist mom Annie - Toni Collette - and psychologist dad, Steve - Gabriel Byrne). Their interactions for the first half of the film are disturbingly devoid of connection; the indistinct musical smearing connotes the absence of emotion. This application of Stetson's pre-storm calm (beautifully apparent on his 2016 release, Sorrow: A Reimagining of Gorecki's 3rd Symphony) is cogently mixed into the film's deliberately empty atmospheres of the deadening household and its dark wooden interiors. The sound of the outside world rarely enters, leaving the household devoid of 'live' acoustics bar the muted taps of a ticking clock. This allows the music to similarly signify that all human progress is halted - and for sudden noises to aggressively startle.

The first sign of the domain's incursion by malevolent spirits occurs when young Charlie (Milly Shapiro) spies laser-like shimmers of blue light swimming across her bedroom ("Charlie"). Stetson layers the earlier snarling bass clarinet line atop a high-pitched bass pulse and multiple bell-ringing drones. Timbres morph as various elements cycle hurriedly and rise in volume before fading away. The impact is as full as any Hollywood orchestral bombast, but the detailing is crisp and lean, not thick and bloated. Film music orchestrations carry on the questionable tradition of being blasted in sound stage hangars; Stetson's scores are always studiophonic. The Hereditary score is a dark doppelgänger of symphonic grandeur, as Stetson employs his wind instruments to perform like soaring strings, gulping cellos and haunting plucks. It's a masterful move, using the vulgarity of saxophones - bass, baritone, contrabass - to simulate the symphonia of a traditional orchestra.

In the memorable scene where Charlie suffers anaphylactic shock as Peter desperately drives her to hospital, her breath is mixed like a guttural vocal track atop Stetson's backing. His sound palette accentuates the mechanics of breath in relation to his instrumental arsenal. Multitracked clicks, taps, spits, coughs and blows rattle and excite Stetson's instruments, as if they are fretfully possessed by sonic poltergeists. That Stetson's unique percussiveness and its rippling noisescapes are welcomed onto Hereditary's soundtrack is a testament to Aster's grasp of the film score's outer limits of sonority. In fact, one can interpret Peter as a human who is slowly transformed into a vessel: the music blows and hums through his hollowed being just like Stetson's aural imaging of Peter. The film's closing theme ("Reborn") uses Stetson's technique of emotive deconstruction from Sorrow, here applied to the euphoric moments of something like Strauss's Alpine Symphony (1915). The impact is like feeling the full spectrum of emotions occurring simultaneously. Post-human transcendence breathed onto the soundtrack.

Wire subscribers can read Philip Brophy's original Secret History of Film Music columns from the 1990s online in the digital archive. Previous instalments of this column published on The Wire website can be found here.

In The Wire 503/504, Seymour Wright appraises the hardcore saxophony of French musician Jean-Luc Guionnet

Jean-Luc Guionnet

Per Sona

Empty Editions DL/LP

L'Épaisseur De L'Air Live

Potlatch CD/DL

French multi-instrumentalist, composer, philosopher and visual artist Jean-Luc Guionnet has been a globally influential figure for several generations of creative peers. He is also one of the great living saxophonists, with an alto voice that uniquely consolidates strands of the instrument's sonic and conceptual history into something powerfully distinct, rigorous, instantly recognisable and future-fit.

In 2021, after 30 odd years of solo performance, he released his first full-length alto saxophone solo recording on Los Angeles label Thin Wrist. Recorded in a semi-open barn in 2018 in Brittany, L'Épaisseur De L'Air (The Thickness Of The Air) was concerned fundamentally with the texture, materiality and ideas of saxophone, sound and space. Here, four years on, are two more solo alto recordings. Though not officially released as a pair, they appeared almost simultaneously. One offers two live realisations of the L'Épaisseur De L'Air material on the French label Potlatch, the other private studio recordings made in Hong Kong and released via Empty Editions.

These sets consolidate Guionnet's voice in documentary form, containing years of situated work. Here, it's possible to hear his playing as the kernel/nexus of a sort of Francophone school of saxophone innovators that includes Daunik Lazro, Christine Abdelnour, Stéphanes Rives, Bertrand Denzler, Patrick Martins, Pierre Borel and Pierre-Antoine Badaroux. It is also possible to find traces of other alto techniques: the M-Base ways of Steve Coleman and Gary Thomas, the lyrical power of Arthur Blythe, the whimper-gnash of Anthony Braxton's Composition 99G, Arthur Jones's Scorpio.

A consistent ambiguity and variety of scale twists, inflates and crushes complex sonic details, dense knots, abrupt nothingnesses across the two discs. Both recordings document astonishingly visceral and cerebral instrument technique, into which musical/philosophical traditions are tied very tight: the saxophone stuff, plus for example study with Iannis Xenakis, workshops with Don Cherry, deep engagement with philosophy (a dialogue with tools in the ideas of Gilbert Simondon in particular feels at the tip of saxophone-homunculic fingers and tongue), mark-making and lines - are all in here, bound up with haptic ways of getting at, and beyond, the saxophone as technology, or back, via bagpipes and other ancient breathed-into, manually worked tools of transformation.

Dedicated to Miguel Garcia, L'Épaisseur De L'Air Live includes two longish in concert solos recorded in Montreuil, in the eastern suburbs of Paris - the first in summer 2024, the second in winter 2023. The alto saxophone fizzes, furry, flinty, furied, fuzzy, hard and soft, large and small sounds accruing and decaying in and out of phase with the force and stress Guionnet applies. The Parisian ghost fuel of the saxophone - from Adolphe Sax's speculative patent to Lester Young's memory palace (and absinthe) - are part of the air through which he forces his ideas, via the horn, into the ears of his listeners.

The longer first piece evolves episodically, in slabs, trickles and eruptions/implosions of ideas as sound that grow, decay and grow again as mouldy blooms, alto alliums of bulbous, pungent forces that sizzle and linger. The heavy, hot sonic reactions that begin the second shorter piece collapse into a long dusty tail of embers. The liveness is salient - we can hear the rooms, the other people there, making and listening, the world in this music.

Per Sona presents 11 exquisite studio solos recorded in Hong Kong, all of them short - between 90 seconds and seven minutes, almost miniature études. These are close, detailed recordings of close, detailed sounds: pied sounds that contain pockets and layers of different types of sonic activity, in different places in the saxophone, mouth and ear at once. Rippling sounds made up of multiple bits emerge out of simultaneous interactions and qualities of the saxophone qua machine. The first piece is a series of giant ascending blocks of complex sonic chunks; the second a cloud-cypselae, blown almost ney-like across reed/mouthpiece tip; the third a columella of growl about which the piece spirals. Sounds of skeleton-feathered lichens ripple in the final track's nutty sonic butter - halfway in, a gargle ends with spat-breath of husk.

In accompanying notes, Guionnet writes, tellingly, of the saxophone, "It was invented; invent music for it in return; always remember that when it falls, its fall does not sound like a saxophone. If it happened to fall, it makes the muffled sound of a ductile metal sheet, or of a bad hardware shop; its body is not sonorous - in which it is a machine; virtually, see by playing it the three dimensions of the metamorphoses of the air column, under the influence of the action; an unstable regime once grasped, maintain it by going with the wave." This gives a sense of the intellectual and physical stuff of the work at play here. "By whom sounds what?" he concludes, "Through what sounds who? Person/per-sonare or this mask which carries in my place a mask that does not belong to me… nor to it." Per Sona is an amplifier, definer and representer of character, identity.

Utterly hardcore and grown up in its humble enquiry and challenge, this is essential 21st century saxophony.

This review appears in The Wire 503/504 along with many other reviews of new and recent records, books, films, festivals and more. To read them all, pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Wire subscribers can also read the issue in our online magazine library.

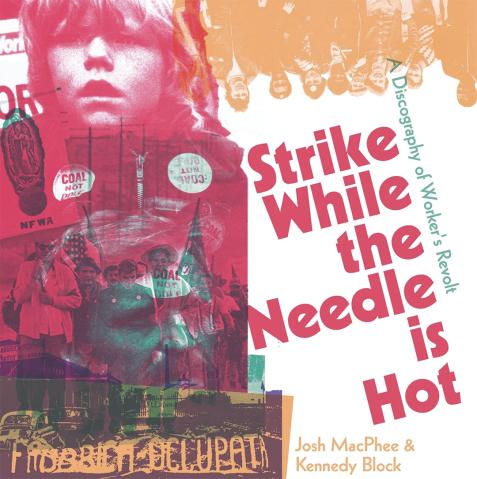

In an extract from his new book, co-authored with Kennedy Block, Josh MacPhee outlines the role of workers' songs and the making of records in supporting labour movements in the US

If producing a record is a tactic, and winning a strike is the goal, then what is the strategy? From studying these records, it's clear that the hopes for them are sometimes singular, other times multiple, often overlapping, and almost always clearly understood and articulated by the workers and unions.The records more often than not speak for themselves when you listen to them, but as most are quite hard to find, or in languages many of us don't speak, it's worth trying to lay out some of the intentions for the vinyl here.

There are two dominant reasons these records are produced: first, to raise public awareness of a strike, and second, to raise money to support the strike (and the strikers, who are by definition out of work and not being paid) - this latter reason is particularly acute for the wildcat strikes, where workers are not getting any support from an official union strike fund. That said, there are plethora of other intentions you can find for these records: to document a struggle after the fact, ie, a "proof of existence"; to build capacity amongst the workers and their supporters - for example, learning how to work together, organising and accomplishing increasingly complex projects, etc; as an extension of this, to build confidence amongst workers by creating "permanent" documents of their struggle; to use as a tool to connect to other workers, often in different industries but facing similar macro economic pressures; and to reach audiences that might not read a pamphlet or a long-format political treatise, but are more than happy to pick up a record they might enjoy.

A handful of records even come out of the practice of militant research, developed by the Facing Reality group in Detroit in the 1940s and 50s, then lifted up and expanded on by autonomous Marxists in Italy in the 1960s. The idea is simple: rather than prioritising academic pursuits by outsiders, workers know their workplaces best, and can participate in the study of their own struggles, and learn from similar studies by workers in other struggles.

While the music and production of these records is surprisingly eclectic, there are some things most have in common. As we'll see, if workers' action produces a record, it is almost always a 7″ single, either because the strike committee doesn't have the resources to produce something of a larger scope, or simply because most strikes don't last long enough to collect material to fill a full LP. The length of a 7″ single is roughly a third of an LP, and its packaging half the size and a fraction of the cost, and thus demands fewer resources to produce. In the pop music market, many singles were released in blank white sleeves, or with "company" sleeves that advertised the record label rather than the specific release. You'll find few of these here. Even if the format was small in stature, it was taken full advantage of. Almost all strike records came in picture sleeves, and many in gatefold sleeves - a double wide cover folded in half, giving the workers/union/solidarity committee twice the space to share information about the strike. In addition, it was not uncommon for the records to have additional information slotted into the sleeves: lyric sheets for sing-alongs, petitions to sign, even some oversized posters which could be hung up in apartments, or brought out to a picket line.

These documents are likely as illustrative of a particular struggle as any union newspaper or pamphlet, and sadly haven't been given their due importance in research on worker organisation. That said, this publication is at best a cursory overview of the field, a road-map to where we might look and dig deeper in the future. I'm interested in the use of vinyl records as a form of agitprop - as can be exhaustively seen in my previously produced An Encyclopedia of Political Record Labels. The effects of my fetish for vinyl shouldn't be understated. Beginning in the late 1970s, and gaining serious steam by mid 1980s, the cassette became a much cheaper and more versatile tool for political organising.

If we had included cassettes and CDs here, the size of this book might have doubled, at least. Both formats are much easier to produce than vinyl, and much cheaper, especially in smaller runs. There are likely many, many homemade cassettes created by workers' strike committees that weren't distributed beyond the picket line. I've been able to find a half dozen without really spending much time looking. But what little research I've done has made it clear that a focus on cassettes and CDs is really another project altogether, and I stand by the decision to use vinyl as a curatorial tool here. Ideally someone else will pick up the thread and follow up with a deep dive into worker-produced cassettes and CDs. But for me, and in this book, the vinyl record functions as both a marker of financial investment and a commitment to mass distribution.

Co-editor Kennedy Block and I propose there are several ways to read this book. To look at any particular entry drops you into a specific strike, more than likely a fight that has been forgotten, at least by those who weren't active participants. Like the records themselves, the entries are modest time capsules, historical markers of punctuated class struggle. But when taken together, they tell a larger story, one of an arc of global conflict, of the gains of workers in the 1960s and 70s, and the re-entrenchment of capital in the '80s. We see fights for wages, shorter hours, and even worker ownership and control eclipsed by increasingly immiserated demands for factories not to shutter and pits not to close.

It's a little brutal to listen to - in recorded real time - utopia slide into desperation, to see how neoliberalism stomped on the neck of hope for meaningful and fulfilling work, replacing it with a panicked need of workers to keep a roof over their heads. It is likely no coincidence that the tectonic shifts towards neoliberalism in workers' perceptions of what their struggles could accomplish appear to run parallel to another big shift, this one sonic. The earliest records you'll find in this book tend towards sounding like direct decendents of old left workers' choruses with their martial songs and anthems (a couple even include a version of "l'Internationale"). Over the course of the 1970s we see a shift towards the inclusion of more pop idioms into the music, first in the form of folk, and then rock, reggae, and finally hiphop (or at least pop rap). While on the surface this may seem a natural progression, it exposes a much deeper and more complex process at work.

While the labour music of the 19th and early 20th century might not be the most exciting to our contemporary ears, it developed out of generations of working class organisation, both in the workplace but also the community. Songs such as "l'Internationale" and "The Red Flag" weren't just sung on picket lines, but in union halls, at pubs, worker's funerals, and solidarity marches. As there was little class mobility in the world, children would learn the songs from their parents, and in turn pass them down to their kids. So the shift towards pop music (primarily Anglophone pop) was not simply a stylistic one, but a shift in relationship to the songs themselves. Labour songs are a social form, to be performed and listened to in a community context. Pop music is a commodity, to be sold to individuals, who develop personal relationships to the music.

This is likely why some of the later records come off as strange, or even worse, completely corny. The records fail musically, as well as fail to give voice to any sense of a coherent working class. And this was one of the projects of neoliberalism, the bio-political replacement of any sense of collective working class identity with the atomised consciousness of individual consumers. We're not labour historians, but hope something can be learned from the stories these records tell us.

The last 15 years have seen a huge upswing in militant labour organising in the United States, from the Republic Windows and Doors occupation in Chicago in 2008 to the huge gains made by domestic workers across the country (such as the rise of Domestic Workers United and their successful fight to pass a New York State Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2010), to the increasingly successful campaigns to organise workplaces like Starbucks (Starbucks Workers United) and Amazon (Amazon Labor Union, affiliated with the Teamsters). Music and audio documentation haven't been a memorable part of these struggles so far, but in the social media-dominated attention economy we live in, it doesn't take much to imagine how music could play a larger role in publicising worker action and encouraging broad support. But even if we set aside these larger promotional concerns for a moment, the records in this book exude the sheer joy of workers singing and marching together, fusing solidarity, and taking their lives into their own hands.

This is an edited extract from the introduction of Strike While the Needle Is Hot: A Discography of Workers' Revolt by Josh MacPhee & Kennedy Block, published by Common Notions Press.

You can read Dave Mandl's review of the book in The Wire 503/504. Pick up a copy of the magazine in our online shop. Subscribers can also read the review and the entire issue online via the digital library.

To make sense of ongoing tech revolutions, a new generation of musicians is making music that metabolises electronic processes through analogue forms, argues Ryan Meehan

The progressive music scene turns to the future in a foul mood. It was detectable in the air last October, as the audience gathered for the first of the evening's two sold out Autechre shows at Brooklyn Steel in north Williamsburg. Here, in the omphalos of the newly-minted Commie Corridor was a display of cultural force every bit as robust as the political one which had recently vaulted socialist Zohran Mamdani to the Democratic nomination (and, in short order, the mayoralty). So why, then, as the Rochdale duo took the stage in their preferred semi-darkness, was the atmosphere cut with an unmistakable current of dread? Perhaps it was the uneasy stagecraft of the Gaza truce, still fresh, or the unreconstructed decorum of post-pandemic concertgoers unable to handle their doses (and sometimes their bodily functions). Perhaps it was a suggestion hardwired into the music itself that, outside these walls, there was a vision of the future taking hold (remember the Artificial Intelligence series?) for which we weren't entirely prepared.

Futurists though they remain, the future Autechre first portended is now largely history. Cloned sheep, Clippy the Microsoft assistant, and the like. Their vanguardist rhythms, swinging like sonic battering rams in 4-D, recede into the foundations of the world to come. Instead, as we attain the quarter century, artists are staking out a vital new position within the looming crisis of the digital as it develops in the here and now.

This tendency takes for granted the dynamic and space-bending possibilities of electronic composition, and accepts them not as grounds for abandoning the field, but as a sporting challenge to their own analogue rhythms. At a time when complex computers and their pitchmen lay claim to as much of communicative life as they can, this metabolic tendency in music emerges as one possible response - not theoretical, but organic; not doctrinaire, but instinctively oppositional. If the metabolic coheres as a specific answer, perhaps it's to the question as to why the world has got so weird lately, and what of that weirdness plays back to us in our music.

Weirdness, of course, can be a source of delight. In 2025, few bands were as weirdly delightful onstage as Fievel Is Glauque, the jazz-pop ensemble shifting around the duo of American keyboardist Zach Philips and Belgian vocalist Ma Clément.

The rare progressive band whose precision feels spontaneous and vice versa, FIG's baroque, fleetfooted compositions hit like bursts of sunshine in a funhouse mirror. Core to their sound is a downright algebraic approach to rhythm, massaged across the instrumentation generally, though special plaudits go to recurring bassist Logan Kane and many-handed drummer Gaspard Sicx.

Another provisional quality of metabolism: though its freneticism can seem to dialogue with digitality, the music itself is produced primarily by hand. This isn't mainly a declaration of Luddism (though maybe it is also that) so much as a reclamation of terrain by enfleshed bodies in the production of what makes those bodies move. Nor is it an aesthetic of purity. Fievel's last album, Rong Weicknes (2024), was recorded "live in triplicate", its final tracks spliced together from overlapping takes à la Teo Macero. That the band commits to re-confecting this sound live (and live previews of new material place their upcoming album high among the most anticipated of 2026) emphasises a concern with human, rather than machine potential. With the serene bounce of a surrealist tour guide, Clément sings faster than you can think, her poetry the kind a computer could only spit out by mistake.

In metabolic songcraft, the glitch, long a point of fascination in digital aesthetics, migrates to a motif of human breakdown under the pressures of the mediated grid.

On the left, attention has turned increasingly to passages in Marx regarding capital's potential to develop beyond the resource capacities of earth - what proponents of degrowth call the metabolic rift. In the last decade, art's attempts to encompass climate change as a subject have found themselves stranded - often frustratingly so - in the passive, the local, and the melancholically topical. A crop of new artists on London's AD 93 label has obvious recent antecedents - the fetid Zappa splatter of Geordie Greep's projects, the high watermarks of Tom Skinner's influence within The Smile - but at its most caustic, this pod-born sound suggests an aesthetic rift to measure up to the deep-tissue wrenching of the planetary one underway.

Brooklyn band YHWH Nailgun is the label's latest rising star, porting their youthful current into sludgy contortions that bring to mind images of ceremonial emetics. And while their mixture of propulsive rhythms (courtesy of the reabsorbed kitsch of Sam Pickard's rototoms) and effects-bent melodies recall Braxton-era Battles to this elder millennial ear, that band's use of digital instruments had the flavour of liberation. The Nailgun, by contrast, sound penned in - all but strangled by the imminent cyborg dawn.

For my money, though, the most promising of this corridor of metabolists are Still House Plants, whose incantatory vocal lines and decaying guitar riffs tilt just off-axis over beats whose cracked precision would sound looped if you couldn't see David Kennedy playing them up close and personal.

Irregular tempos and faltering structures seemed designed in advance to resist algorithmic training. As climate politics endures historic setbacks in the West, nascent popular outrage at the AI data centre boom's resource intensity (alongside outcries against music's unique role within the data regime) may provide a previously listless creative counterforce with a potent new metaphor for attack.

Some warriors in this emergent battle are happier than others. A founder of Darkside, one of metabolism's most direct precursors, guitarist Dave Harrington applies the intricate compositional style he first refined beside Nicolas Jaar's minimal post-dub atmospherics to his second band's cheekily analogue arrangement.

Taper's Choice styles itself as a supergroup (just about all of its elements of style are overtly over-styled) looking to supercharge the high-participation jam scene from its progressive fringe. Last year, the ensemble - which includes Real Estate bassist Alex Bleeker, Arc Iris keyboardist Zach Tenorio Miller, and Vampire Weekend drummer Chris Tomson - released their first proper studio album, after a compilation of songs ('concrèted', one imagines, in a method not dissimilar to Fievel's) and a string of - what else? - live tapes. A mixture of balloon bounce and rapid-eye flutter, Prog Hat holds an affinity for the gentle dislocation of 70s jazz fusion. Is it a stretch to compare its supple geometry and bold colour to that other, utopian metabolism, of Tange and Kurokawa? Harrington conducts the marathon-like "Dave Test" with an eye for microstructure, all thrashed into shape by Tomson's relentless stamina. If Taper's swings, it's at a rate your feet must first calculate to catch up to.

Which returns us to Autechre, and the ambiguous future of the human-technology interface, in which music is both figure and ground. A surging appetite for vanguardist rhythms perhaps only awaits the breaking of a figurative dam, the blowing of a metaphorical pipeline, that the metabolic turn can provide. For this generation, it may be that the pessimism of the intellect is a precondition for a renewal of the optimism of the will. Time and again, where democracy elevates a new political regime, its success can depend on the rise of a cultural one in tandem. Will metabolism play such a role? Predictions are a parlour game, but those that clamour for shibboleths of a "left with no future" will at the very least have to dance to the reality shifting beneath our feet, and contend with the eternal truth of Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park - that life finds a way.

You can read more critical reflections on underground music going into 2026 in The Wire 503/504. Wire subscribers can also read the issue in our online magazine library.

In his latest Secret History of Film Music column, Philip Brophy explores how the signifiers of Black musics in Swarm are fragmented to indicate its main character's psychosis

What does it mean to compose music today? Is composed music a creative act or a procedural action? An original expression or a contextual response? A conceptual performance or an industrial gameplay? And if it is one or the other, how do we perceive it as positive or negative? I'm perennially excited by these notions - especially when a film score sends my head spinning into their interrogative possibilities. Michael Uzowuru's score for the Prime mini-series Swarm (2023) spun my head considerably.

The premise is stark. Dre (Dominque Fishback) is a rabid fan of Ni'jah (a twisted simulacrum of Beyoncé and her Beyhive fanbase). She embarks on a killing spree, targeting people on social media who hate on Ni'jah. Graphically unsettling and tonally diffuse, Dre's picaresque journey turns Dante's Inferno upside down and pumps it full of Black aspirationalism to exploding point. Created by Donald Glover and Janine Nabers (whose previous series Atlanta is a meltdown of Samuel Beckett, Melvin Van Peebles and OutKast), Swarm pulls an even tighter focus on the sociocultural complexities of Black music, here pivoting from the hemmed-in machismo of trap and rap to the goddess hysteria of R&B and pop.

Ni'jah's songs are sung and written by Kirby Lauryen, with selected co-writing and production spread between Glover and Uzowuru, among others. Childish Gambino touches are evident, and all tracks are skilled parodies of digital soul, gushing with stacked harmonies. "Something Like That" collapses digital simulations of vocal cooing with gospel-tinged organs and percussive thrumming a la Kate Bush's ethnographic backings. Kirby's AutoTuned lines layer female and male tones in a heady pansexual mix. "Agatha" harks back to seminal Timbaland productions for the late Aaliyah, awash in slurred breathiness and lo-fi Ngoni licks. "Big World" fuses microhouse and elegant sophistico vocals. The bouncy Vocoder jaunt of "Adventure" conjures a trappy limo party as remembered by college grads. "Hahaha" and "Sticky" are pumped with multi-genre crosswired stylistics, making both hard to characterise.

Scattered across the series's seven episodes in disruptive edits and interrupted passages, these songs point to the magical breath of Ni'jah, who has the mystical power of a Black diva to excite her 'swarm' of fans. But unlike (for example) the soaring positivity of Hollywood's flirtations with Black goddess music - from The Bodyguard (1992) to Glitter (2001) to Sparkle (2012) to Trap (2024) - Swarm posits Ni'jah's songs as a type of 'broken' soul music. The polyglottic gumbo of ballads and anthems for Ni'jah do not shy away from how the spiritual Beyoncés and heartache Kanyes of the world produce music that is stylistically fractured, compositionally kaleidoscopic, digitally processed and authorially aggregate. 'Broken' soul describes equally this technological shift, its marketplace redefinition, and the psycho-therapeutic aspect of how fandom now links to these mystical figures with impossibly affective voices.

At the core of Swarm's broken world is the psychotic character Dre. Dominique Fishback's stellar performance (maddeningly numb and unpredictable) breaks the series's narrative momentum continually, pushing the shared notion of 'serial' story and 'serial' killer into hitherto unexplored territory. Uzowuru's score is a selective rearrangement and reconstitution of the sonic shards of Ni'jah's songs. Sometimes they seem to be literal fragments from the songs, but mostly they are echoes of recognisably similar elements: single sounds from drum machines, single chords from digital keyboards, processed textures of clipped vocal utterances. An aural ouroboros is formed: the score comes from the songs which are studio-composed from the type of sonics of the score. This acousmatic mirage evokes the bond between Ni'jah and Dre - who in the first episode makes it clear: "Ni'jah knows what we're thinking and she gives it a name."

With this declaration, Dre is defending Ni'jah to the sleazy boyfriend of her tweenhood friend, Marissa, with whom she now shares an apartment. Dre's announcement triggers an ungainly sound: a badly sampled vinyl scratch of an indiscernible source. This squawk is a sonicon for Dre's cracked personality. Like Grand Mixer DXT's trademark scratch of the Vocodered "fresh", it is her call sign. Uzowuru uses it to forecast Dre's loss of control and unmitigated rage; it will progressively increase in presence and density in the score as the story lurches into widening expanses of psychotic violence. (To my mind it also recalls the pitch-wheel bending of Major Lazer's "Pon de Floor", the basis of Beyoncé's "Run The World (Girls)".)

When Marissa decides to shift out of their apartment and live with her boyfriend, Dre's world falls apart. The squawk sample increasingly and erratically haunts the soundtrack, variously merged with kalimbas, cellos, noise drones and symphonies of swarming bees. All of Uzowuru's 'cues' are tied to Dre. Accordingly, they are weird sonic collages desperately trying to pass themselves off as 'music', just as Dre masks as sane, always hiding her murderous bent behind inscrutable logic and motives. In fact, each episode takes place in a different time in a different state, presenting their chapters as spatio-temporal ruptures in Dre's life as she obsessively tracks Ni'jah's tour schedule in the deluded belief that one day she and Ni'jah will be besties. Dre's outward appearance, her living conditions, her employment situation all make her nearly unrecognisable in each episode. Uzowuru's score placement is moulded by these ruptures.

In a radical move that these days seems far more commonplace in television than cinema, Swarm is a meta-textual labyrinth engineered less by plot and character and more by chance and psychosis. Squiggles, not arcs; lesions, not persons. Episode 6, "Fallin' Through The Cracks", is a sharp send up of long-running tabloid true crime shows like The First 48 and Snapped. It has no tonal connection with the series, and uses none of the actors, nor any of Uzowuru's music. Episode 5, "Girl, Bye", paints an unexpected and unsettling portrait of Dre's childhood and her relationship to Marissa. A single cue by Uzowuru is sounded right near the end of the mostly silent episode. All the other episodes possess their own equilibrium of song tracks, music cues, and sono-musical collages. The viewer/auditor is refused any thematic musical flow to aid in riding the emotional tides and sociopathic waves of Dre.

The final episode, "Only God Makes Happy Endings", devolves into the ecstatic, sensual world of Ni'jah's music, shifting from her disembodied voice to her performative body, when Dre finally gets up close to her idol. Weirdly - magically, even - Uzowuru's music becomes the world of Ni'jah as embodied within Dre's schismatic and dissociative headspace. From awkward squawks of scratched audio to the glistening symphony of 'devangelical' music, Swarm's soundtrack stitches together the titbits megastar divas disseminate to their swooning fans: 'broken' soul for Dre's broken mind.

Wire subscribers can read Philip Brophy's original Secret History of Film Music columns from the 1990s online in the digital archive. Previous instalments of this column published on The Wire website can be found here.

From the mainstream to the margins, bands were once again in decline in 2025, writes Antonio Poscic

For several years, the supposed death of the band has been cropping up in state-of-the-nation style music discourse. The obvious culprit? Financial hurdles of the sort that even successful bands can no longer overcome. This autumn, Garbage vocalist Shirley Manson launched a diatribe against the unsustainable realities of touring. Meanwhile, UK post-punk four piece Dry Cleaning were forced to postpone their US concerts due to "increasingly hostile economic forces".

Ignoring the rockist winds that circulate the topic alongside the alleged downfall of guitar music, the cultural decline that band-made music suffered in the mainstream is clear by looking at the 2025 streaming charts. Here, groups are few and far between, relegated to the lower tiers, while higher placed entries are either legacy acts (The Rolling Stones, Coldplay) or K-pop groups.

Around them is a sea of solo projects, across genres from hiphop, to electronic music, to bro country, for which musicians are often motivated to present as cultural icons and social media influencers. Going at it solo, it would seem, is both more profitable and better suited to social currents. However, blaming harsh economic environments alone can obscure the nuances of the situation.

In a 2012 letter announcing the dissolution of his Chicago Tentet, Peter Brötzmann lambasted "the everlasting critical economic situation, actually with no expectation for better times", musing on how "the financial situation forms and builds sometimes the music". He closes the announcement with a dejected rhetorical question: "Who can afford to travel with a quintet nowadays?" Surveying the landscape of experimental music 13 years after Brötzmann's letter, the sobering answer is, not that many. For the 2025 edition of The Hague festival Rewire, one of experimental music's flagship European festivals, only a fraction of the immense lineup was occupied by bands, even with the definition of the term stretched to its extremes. Further out, the pattern repeats at Utrecht's Le Guess Who? and Kraków's Unsound.

Meanwhile, outside the big names (eg Jazzfest Berlin), free jazz and improvisation focused events across Europe are forced to balance their rosters by relying on ad hoc groups. Even avant rock and more audacious metal festivals, such as Roadburn in Tilburg, whose bread and butter are bands, have begun to rely on solo projects.

But, in the same letter, Brötzmann pointed out an overlooked tendency working against experimental bands: the rote and patterns that settle in over time. "Hanging together for such a long time - with just a couple of small changes - automatically brings a lot of routine," he writes, "for my taste it is better to stop on the peak and look around than gliding down in the mediocre fields of 'nothing more to say' bands." Does the dissolution of the band prompt greater creativity among its ex-members?

If economic challenges brought the band down to its knees, technology gave it a hard kick. Home studio hardware and software, digital workstations and programming languages free artists from the power dynamics and creative restrictions characteristic of bands. Some of the essays in Routledge's 2024 volume The Ontology Of Music Groups make the case that intra-group relationships can stifle innovation and creativity, and point out that social structures that emerge in a band are often patriarchal in nature, and eventually collapse under the prevailing influence of its most prominent members.

Bedroom pop and black metal led the way, showing the potential for one person, DIY projects to result in a myriad of stylistic permutations, while being conducive to unorthodox experiments and accessible to more marginalised people. Furthermore, the solo practitioner need not pay for prohibitively expensive rehearsal spaces, and much could be achieved even during Covid lockdowns, using the internet as a tool for dissemination. Comparing The Wire's 2025 Releases of the Year chart with those from 2020, 2015 and 2010 shows the decline in the representation of bands in the latest lists, especially when excluding long-established groups like Stereolab, Tortoise and The Necks.