His love for cycling reinvigorated, Alistair Fitchett spent much of 2025 colouring in maps.

Colouring The Lanes

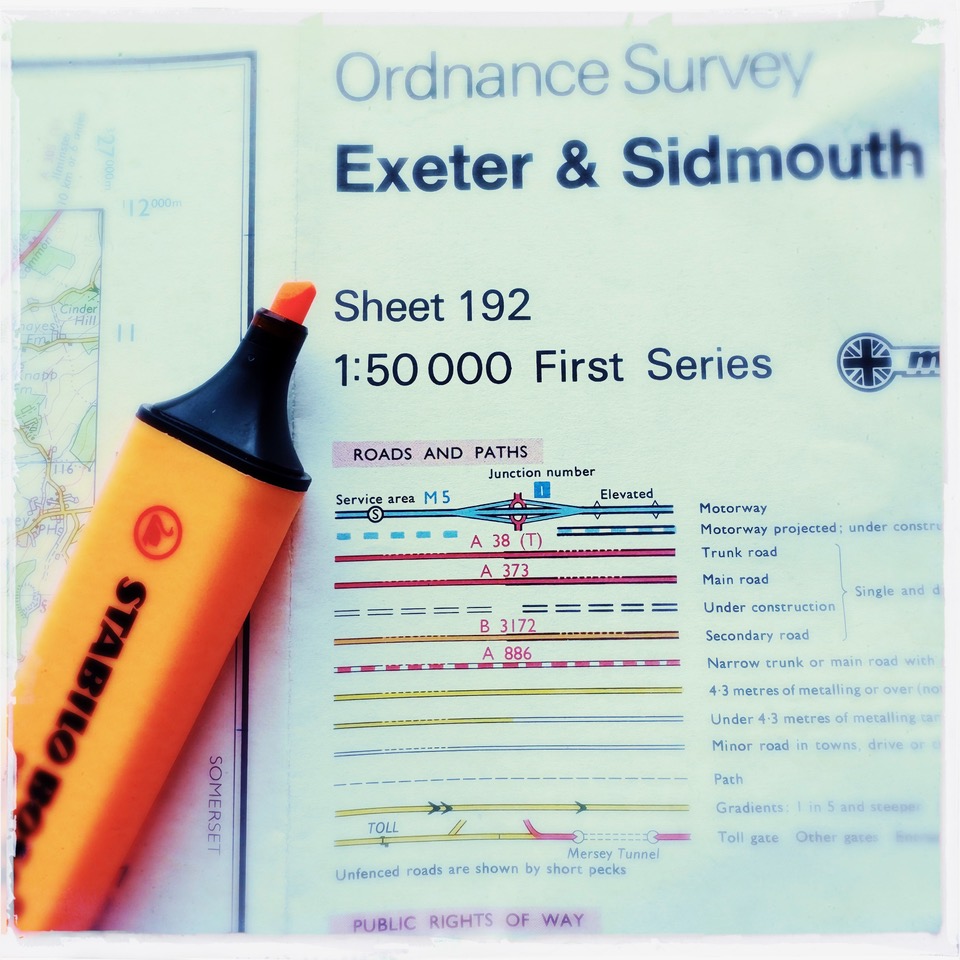

Much of 2025 has been spent colouring in maps, recording roads and lanes down which I have cycled. Most of this colouring activity has focused on sheet 192 (Exeter and Sidmouth) of the Ordnance Survey 1:50000 First Series from 1974, although surrounding maps have also been touched by my pen on occasion. I suspect part of the reason for doing it is the need to evidence existence, just as writing these words is, whilst another might be the strain of completist collector in me. Whatever the reasons, the desire to colour in as many lanes as possible is strong and has, alongside investment in an electric road bike (originally as a means of getting back to health after a spinal issue, ahem, 'back' in 2024) rather reinvigorated my love for cycling.

The first assaults on the map are exercises in memory retrieval. What roads and lanes have I ridden in thirty three years of living in Devon? Quite a lot, as it turns out, and it is particularly gratifying to let loose with the highlighter pen on those larger roads that I would never choose to ride on now, like the A3052 from Sidmouth to Exeter. This was one of the first Devon roads that I cycled back in 1988 when I made a cycling tour of parts of the South West visiting musician and fanzine-writing friends. It is immeasurably busier these days and now it is mostly an obstacle to cross rather than something to travel along.

I do cross this road early on my ride of June 27th, which is the first of my targeted colouring routes (I'm aiming to fill in a bunch of lanes around the hills of Northleigh in the designated East Devon Area Of Outstanding Natural Beauty), and also one of the rare occasions when I take the bike in the car, riding out from the beach car park at Branscombe. The route ends up being 68km and 1600m of elevation gain and is gloriously rewarding. Around Harcombe, with its 22% inclines, a series of fluorescent pink signs decorated with stencils of dinosaurs punctuate Chelson Lane. Their meaning is never clear, but I assume them to be for different camp sites as there are vans and tents dotted in fields, whilst another sign promises a Fun Dog Show the following day in 'The Party Field'. Categories include 'Best Sausage Catcher', 'Waggiest Tail' and 'The dog judges would most like to take home'. I hope they do not succumb to the temptation.

Elsewhere on this ride I finally take the opportunity to go down past the Devenish Pitt Riding School, the signs for which C and I have seen many times on drives to/from swims at Beer and about which we usually say to each other "I'm Devenish Pitt" in the style of Steve Coogan saying "I'm Holbeck Ghyll" in series one of The Trip. As another aside, Devenish Pitt (retired Army Major, I think) is surely a character out of a great lost Golden Age detective story, no? In truth the riding school is utterly charming, tucked away on a typically steep hillside with views east to Farway and the river Coly winding its way towards the coast, where it merges with the Seaton wetlands and reaches the sea at Axmouth Harbour. This is where I eventually head, after several loops around the hills, following the Axmouth Road and riding over the old Axmouth Bridge. Built in 1877, it is believed to be the oldest surviving concrete bridge in England and on my map is still the only bridge across the river at this point.

July 2nd is a ride from home, out west and north this time on lanes I've ridden many times. The exception, and the main reason for this ride, is one very short stretch that leads down to and then back up from Pennicott Farm near Shobrooke. At the farm I've hit rush hour for the sheep, so gates are closed across the yard through which the lane passes. The farmer apologises, but it's fine to stand in the shade for a few minutes and watch others at work.

The following day I do a longer ride and fill in more new lanes in East Devon, finally detouring off the road from Hemyock up to the airfield at Dunkeswell, which I have ridden innumerable times, to visit the ruins of Dunkeswell Abbey. It's a glorious high summer day and I meet a couple from Swansea who have walked to the Abbey along the lane that skirts the Madford river. We talk of the not-so-ancient routine of 'two sleeps' at night, which the monks at the abbey would certainly have practised, and about the liberating pleasures of electric bicycles.

The 13th of August finds me out near Dunkeswell again, this time on a mission to colour in some of the lanes around Bolham Water and particularly to ride along what used to be one of the runways of the Upottery Airfield. The approach to the airfield from the north is on a narrow lane, even by East Devon standards, alternately potholed, scattered with gravel and/or muddy, even in one of the driest and hottest summers on record. Often there is grass growing down the middle, a sure sign of a lane less travelled. Old maps show the lane joining the ridge road at Clayhidon Cross, but since the construction of the airfield in WW2 there must have been little reason to travel along it. Then, like now, the only traffic must be for Middleton Barton farm, for the only other building, the quaintly named Trood's Cottage, is now a crumbling shell. The landscape that the lane crosses is largely wooded, dipping down to the Bolham River and then back up again to the airfield, which explains the lingering dampness. Emerging onto the remains of an airfield runway is quite an odd experience. The surface turns suddenly to concrete, the wind whips across the Blackdowns and the ghosts of American airmen and parachutists linger on the periphery, mixing with burnt out shells of caravans and motor cars, for the airfield now plays host to banger racing and monster truck shows. How times change.

It occurs to me now that I must have passed the Upottery airfield site back in 1988 on that first visit to the South West, for my ride to Sidmouth had started in Taunton and I must have ridden out on the Honiton Road, up Blagdon Hill and then across the ridge of the Blackdown hills. It must have been a headwind that day too, the struggle bleaching out all memory, and the proof that the suppleness of youth is no match for the motorised assistance of age. Still, it's good to piece these fragments of memory together and colour those routes some 37 years later.

On September 4th, a day before driving to Scotland for my mum's 93rd birthday, I colour in some lanes on Sheet 191 (Okehampton and North Dartmoor), ostensibly to visit the grave of author Jean Rhys in the churchyard of St Matthew Church, Cheriton Fitzpaine. I also track down what I think was the cottage in which she lived, on the end of the terrace of Landboat cottages. There is no plaque commemorating the fact that Rhys lived here and I cannot decide if this is a shame or a relief. The latter, I think, for there is something rather splendid about keeping such mysteries at least partially caged.

In October I do a few rides out east again, through Kentisbeare, where I always nod to the resting place of another author, E. M. Delafield, whose Diary of a Provincial Lady is one of my very favourite books. On these autumnal rides I head up from the village towards the pumpkin farm on Broad Road, colouring a lane at Windwhistle Cross, an 'Unsuitable for Wide Vehicles' one leading from Broadhembury to the A373 and a couple of others that lead only to farms.

On November 1st I visit the area again, this time to fill in a lane that climbs to Blackborough past All Hallows farm. The landscape is damp and grey and I am happy to not have ridden here a day earlier when the ghostly presence of generations past could easily be imagined haunting the crossroads where the finger sign is so weathered as to be almost illegible. The landscape is starting to look more like winter, though there are still enough leaves on the trees to feel like autumn is clinging on for a few more weeks at least.

Come the end of the month, however, and the low sunlight shining through bare branches insists that the year is reaching its conclusion. On a ride close to home I finally take the opportunity to ride along Harepathstead Road, a lane at the foot the Ashcylst Forest close to Westwood, where I am delighted to see that the festive Christmas Bouybles are hung once again from the large Oak tree at Wares Cottages. These remind me that whilst it will no doubt continue to be enormously enjoyable to colour in lanes not yet travelled, it is equally important to keep revisiting the treasures I know and love.

Mark Hooper looks back over a year that put us all on Boil Notice.

Boil Notice

As I'm writing this, in early December, my entire town is on 'Boil Notice'. It's been almost two weeks since the water supply was turned off in Tunbridge Wells. The irony is lost on no-one that a town owing its existence - and name - to the discovery of a natural spring now has no water. (Although, funnily enough, the spring itself, recently renovated and monetised by an enterprising local, is still bubbling away quite happily, next to a vending machine selling bottles of the mineral-rich elixir for around £7 a pop.)

The problem, according to a slow-drip of corporate comms that I'd trust as much as the tap water, was a 'bad batch of coagulant chemicals' added to the treatment plant. Which fills you with confidence from the outset. To be fair, water returned to our taps after six days but, as of now, we are helpfully informed that - and I quote in full - 'Your water is chemically safe, but a potential fault in the final disinfection process means you must boil it (and let it cool) before drinking.' Which is as clear as the water coming out of the taps (before letting the sediment settle, as advised).

I'm aware that all this may sound like a very First World problem. Especially as I only returned to my hometown on Day Two of the very middle-class emergency, having been on holiday in Tunisia, where of course we were advised to only drink bottled water because our sensitive Western-softened bellies might not be able to handle the coagulant-free variety.

But, as frivolous as it may sound, the effect was more traumatic than I expected. It was like a mini Covid flashback - the deadlines and messages changing daily, the home-schooling and gallows humour unlocking some residue of lockdowns past, mental muscle memory kicking in. It also felt like an apt metaphor for a deeply weird and unsettling year, one that put us all on Boil Notice as we were gaslit and ghosted on an industrial scale. The simmering anxieties were partly why I decided to opt out of social media, making one last virtue-signalling post on my birthday in February, before deleting my data from Meta (a much easier process than you'd expect - although I now keep getting 'Memory almost full' notices on my new laptop from all the backed-up Instagram images I downloaded).

The idea was to step away from the increasingly binary debates that are no good for anyone; to spend more time in nature; to wait for the storm to break.

I'm not sure it worked entirely. For a start, my social media detox wasn't total: I kept my LinkedIn profile going, to keep an eye out for jobs. No joy there. In fact, if anything, it only added to the tension. Not only did it confirm that everyone is 'Open to Work' these days - even those few still doing the hiring - but it also confirmed my worst suspicious about social media. It seems to be dominated by tech-bro wannabes giving you five key but irrelevant takeaways for your business while trolling you about AI, ICE, KPIs and ROIs. But in between the slop and the dross there are still the odd gems - mainly from witty, out-of-work admen (and -women) with newfound time on their hands.

With my own spare time, I vowed to spend more times doing rather than thinking about doing. That meant trips to Bristol to watch the brilliant Idles at their hometown-square gig, as well as GANS, my favourite new band of the year, who I saw in three different towns, from a tiny pub basement to the Troxy, each a fantastic, visceral, life-affirming treat. The Bristol gig was my favourite, because it's my favourite city. While the rest of the world plummets to hell in a bile-powered handcart, it remains a sanctuary of good sense and good vibes. A place where you're a Bristolian first and anything else is secondary if not extraneous; where a nod's as a good as a welcoming West Country hug, where everyone's your mate, 'moi darling' or 'moi lover' (especially when said with gusto between two burly heterosexual males). Some of my favourite people live in or come from Bristol (the former just as important, because they have actively made the decision to be there). This includes Johnny, my oldest friend, who I never see enough, and who can always be relied on to provide the best counsel on life, music, politics and flags. Needless to say, he loved GANS too.

Other musical highlights this year included The Beta Band at the Roundhouse - where we randomly bumped into Marc Wootton, my comedy hero (not to be confused with Dan Wootton, AKA the worst man in the world). The Betas were of course amazing - any gig that starts with Bowie's 'Memory of a Free Festival' played at full blast is incapable of failing, never mind the 90s nostalgia. (On that, it would be remiss of me not to confess I went to see Oasis at Wembley, along with approximately 20% of my generation. I'd never seen them before, and as the years have passed, I've bought into the agenda that they embody all that was wrong with 90s laddism, and I convinced myself that I was doing it for my 10-year-old son, who had never seen anyone before, and who has become - Dad bias notwithstanding - a very talented guitarist. The first song he ever learned to play was by Oasis, followed by his second. When I told him it was amazing that he could play two songs, he replied, 'To be honest Dad, it's pretty much the same song.' Anyway, they were incredible. Of course they were. Even better was Richard Ashcroft. I shed a tear when he dedicated 'The Drugs Don't Work' to 'All those we've left along the way'. As we shuffled our way out at the end, a random scouser high-fived me and called me 'Dad of the year' at the end too, which was nice.)

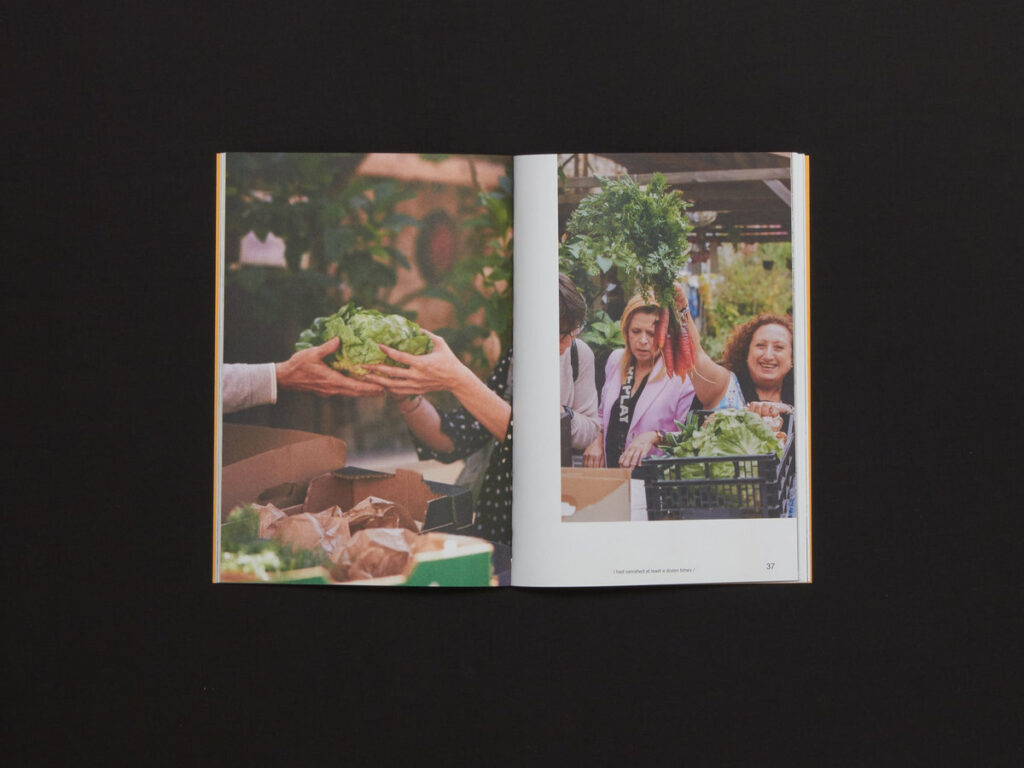

The Social Street Party in June was another highlight - one of those events where you can guarantee to catch up with the best of the best without any pre-planning - this year Stephen Cracknell of the Memory Band, Mathew Clayton (and some post-planning), plus my old mates Mike and Val and a cast of hundreds made it an afternoon to remember (don't remember the evening, tbf).

At this point I have to give a vigorous nod to KIF's Still Out, the brainchild of Will Cookson and Tom Haverly, which Will had mentioned to me in passing when we met at last year's Neo Ancients festival in Stroud. At the time, I made the sort of noncommittal noises one does when someone mentions a personal pet project. But when Will followed up with a link to the trailer and soundtrack (the result of a roadtrip from North Yorkshire to North Devon, inspired by the KLF and directed by Rufus Exton), I was uncharacteristically effusive. It felt like the soundtrack to my own off-grid ramblings, a connection between the past and the present. Fortunately, a few other people agreed. The film was screened at The Social, while the album was listed among Disco Pogo's top ten of the year. My all-time favourite album, however - of this or most years - was Blood Orange's Essex Honey. A deeply human study of loss, written and recorded by Dev Hynes as he returned to the UK to look after his dying mother, it feels like the perfect summary of this weird year, with people forced to question their sense of belonging and self. Talking of which, there was a rare moment of perfect irony when the Tories' own have-a-go antihero Robert Jenrick singled out the Birmingham district of Handsworth as a 'slum' that showed a lack of integration. The irony being that Handsworth's most famous resident, the late, great Benjamin Zephaniah, did more for integration than any other Briton I can think of (if, by integration you mean a sharing and blending of cultures, rather than wholesale submission to one by all the others). In lieu of a rant against the jackboot-lickers that are getting far too much airtime at present, I'd rather leave you with a few choice words from our unofficial poet laureate who, in his poem 'The British (Serves 60 Million)', lists the many nationalities that make up our nation, urging us to:

Leave the ingredients to simmer

As they mix and blend allow their languages to flourish

Binding them together with English

Allow some time to be cool

Add some unity, understanding, and respect for the future

Serve with justice

And enjoy.

We're still on boil notice, waiting for the storm to break.

*

You can listen to Mark's soundtrack to this piece here.

As a yet-to-be-built bungalow beckons, Sean Prentice concludes his relationship with a mysterious field.

Dog-Walking On Faerie Soil

The man that ploughed the ley would never cut the crop.

— T. D. Davidson, The Untilled Field, Agricultural History Review. 1955.

There are in or near Worcestershire a great many fields and other places of the names "Hoberdy", "Hob", "Puck", "Jack" and "Will" …

— Jabez Allies, On the Ignis Fatuus: Or Will 'O' the Wisp, and the Fairies, 1846.

In the last twelve months, as I enter my sixtieth year, as my disability progresses, as my mobility fails more certainly, a yet-to-be-built new build bungalow beckons, more insistently, and I begin the process of uncoupling from the slightly damp mudstone cottage, built in 1873, where I have lived for a decade longer than I have lived anywhere else ever. As part of this stilted farewell, which like all life changes is a variety of mourning, I have decided once and for all that I have to ignore a field — or rather to ignore The Field, to finally say, after all these years of unpredictable and confusing behaviour on its part and frustrating attempts at communication on mine — "this is the end for us". The field in question isn't much to look at — a standard issue agricultural space fringed by hawthorn and blackthorn, boggy at the farthest corner, and bounded at one edge by the Worcester-Hereford line, yet it seeps a rare order of liminality. The location itself, on the edge of the village bounds, beyond the remaining boundary oaks, lends itself to be another order of periphery, as a space between the everyday and down-to-earth and uncertain supernatural worlds. During the fourteen years of being its neighbour the field has oozed enough unplaceable strangeness to make me wary and suspicious of its true identity and possible intentions. The familiar becomes unfamiliar just beyond our back hedge. Walking the bounds of its almost-square I have on occasion become temporarily unstuck in time, I have heard discorporate voices at my shoulder and strange, unplaceable music. I have questioned both where and who I am.

The field is named as Jack Field on the 1841 tithe map of the village. I already knew enough to wonder about that name. There is of course Every Man Jack, Jack Tar, Jack the Lad indeed Jacks of all Trades and although once upon a time every John was also nicknamed Jack I had an inkling that the Jack of Jack Field wasn't a person at all, at least not a person in the strictest sense. Jack Field always puzzled me. In the adjacent Broadley Ground, where the shorn wheat stumps crunched underfoot, each harvest brought to the surface fresh shards of long broken crockery. I have two pickling jars full of this field-edge flotsam — blue and white, the odd piece honey-coloured slipware — evidence of harvest repasts gone by — but I seldom find ceramic or anything much at all to indicate human agency and industry in Jack Field and surmise that it had rarely been cultivated or laboured-upon before living memory. Thumbing through a copy of George Ewart Evans' The Pattern Under the Plough I find a reference to survivals of the belief that certain uncanny fields within the parish should be left untilled, and that these fields 'sometimes called Jack's Land' carried a taboo. I think of Jack in the Green, close kin to the Green Man, and his association with fertility rites, a bringer in of plenty — and that givers in folklore are often takers also. Jack, within this context, I learn, was the generic name afforded to many of the sprites, imps, and other members of the Secret Commonwealth that might slip into human form bestowing good fortune or alternatively cause all manner of mischief. So it was understood that not to exploit the "fairy soil" of such land was a due, a deal made on behalf of the whole community to appease capricious supernatural forces and in so doing safeguard against havoc and mayhem, mischief and misfortune. I research further and find that the practice of sacrificially offering up land in this manner — in many instances on a farm by farm basis — was, in other parts of the British Isles, also referred to as the Goodman's Croft, Gudemen's Fauld, and Goodman's Fauld. Clooties Craft, Jack Craft were other variations. Here the word croft for enclosed farmland is as much Middle-English as Scots and the old time Gudeman doesn't contain the adjective good with an anachronistic spelling but the Anglo-Saxon noun god — the Germanic Guda. Meaning I think that the Gudemen's Fauld was once really the god-man's field, a field belonging to a supernatural being. The church and parliament preferring a different god-man crusaded hard to stamp out these practices throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, particularly through the use of hefty fines but also by the threat of invoking laws pertaining to witchcraft. Ultimately it was economic pressures and which forced farmers to risk paranormal calamity and cultivate all available land and the practice dwindled and then died a death during the course of the nineteenth-century, with any remaining unworked field falling foul of the Cultivation of Lands Orders enforced for the duration of the First World War. It is possible to see the Enclosure Acts of the early nineteenth-century as an action which extended to the eradication and enclosure of folk beliefs along with the commons and earlier field systems. Now Jack Field, perhaps like the whole of the countryside, might be described as a "post-supernatural landscape" although only in that the supernatural has been pushed aside, trampled, and forgotten, in favour of secular common sense and measurable financial concerns.

Earlier today I attempted to walk our dog in Jack Field. A good portion of it is presently out-of-bounds, divided by an ever-shifting latticework of temporary electric fencing, and the right-of-way down along the stream to the railway line has been churned up by so many sheep. The cold clay is waterlogged and slippy and half-rotted beets from the year before stick out of the soil like tiny bleached skulls. It is unsafe underfoot and I am already irked when I meet another dog-walking villager coming the other way, his own dog one of those overly enthusiastic breeds, and he and I fall into discussing the weather (which until the day before yesterday had been "mild for the time of year") and also the sudden absence of access through the neighbouring fields, and he concludes "O' well never mind…I'll circle 'round…join the footpath over there…" gesturing a semicircle "makes no odds…" and yet it makes significant odds to me. More than I can say as I hobble on. More than I have vocabulary for. The landowner believes, perhaps understandably, that Jack Field is his, but it isn't. The farmer believes equally that the soil he leases from the landowner is his to cultivate or graze as he pleases, but he's also mistaken. If land can be owned at all then that ownership resides elsewhere and beyond our ken.

Now, as I write on this cold and wet afternoon, with an early fire in the hearth, I am already partially elsewhere, partially ensconced in that soon-to-be-bungalow-land, and with this shift comes an acknowledgement that my relationship with Jack Field is coming to some kind of natural — or extra-natural conclusion. I have perhaps, like I accept the inevitability of my physical decline and a future wheelchair usage, accepted when it comes to Jack Field I am left with far more questions than answers — an ending without closure. And in the same manner I have inadequate language to describe the nature and nuance of my disability as I experience it over time — so will not even attempt to, I will also not attempt to describe who or what I once met crossing the field in the first light of morning in the that first year here. Suffice to say that the fellow I encountered on that occasion was more foliage than flesh and blood, and he wasn't walking a dog.

In Edinburgh, Tamsin Grainger spent 2025 on a quest for a hidden river.

This year I have been looking for the Granton Burn in Edinburgh where I live. It began with a New Year Resolution to get to know the area better through planning a series of walks. What I needed was a good map. The February date coincided with the Festival of Terminalia, an annual celebration of the Roman god of boundaries, Terminus, on the 23rd. If I found a chart showing the boundaries, maybe I could get a measure of the place, define it better and identify its features. I was curious to discover who lived there before me, who the indigenous species and people were.

It was clear that the Firth of Forth estuary was the northern perimeter, and contemporary maps showed Ferry Road, a main east-west traffic artery, as the southern. However, nobody seemed to agree where the eastern and western edges were. Local organisations such as the Community and Parish Councils provided plans which differed. Street and building names that included the word 'Granton' were spread over a wide area, some to be found in neighbouring zones. Turning to historical documents, I discovered that the Wardie and Granton burns — Scots for small river or stream — were listed, but where were they? Not on my phone app, that was for sure.

There is an old map showing the City of Edinburgh in colour with Granton in white as if it barely existed. Only a number of thread-like lines depicting fields, one or two boxes denoting properties, and some grassy tussocks and tree shapes can be seen. There was once a castle, the website for the existing garden and dovecot told me, but in 1544 the English invaded and it was sacked. I had very little to go on.

A Granton Community walk - outside Caroline House

Here is where the community walks came in useful. Local people who joined me on my search said that although the Wardie Burn cannot be seen, its route roughly followed the current A903. I had noticed musty, damp smells near where that road meets the end of mine. I could occasionally hear the shrieks of foxes and other small creatures coming from somewhere unpenetrated by street lamps. My walking companions confirmed, yes, the Burn used to run in a dell there between two slopes, maybe still does. Now I knew the eastern limit.

The Granton Burn remained elusive.

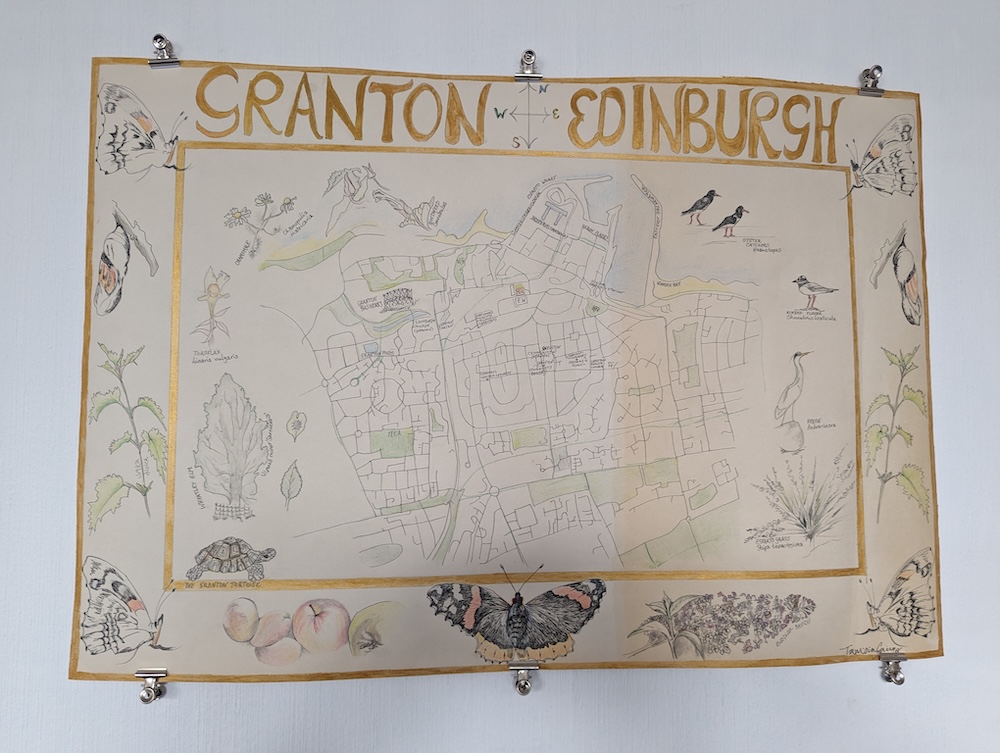

On my March walks, when I was close to what I guessed was the edge of the area, I started asking people, "Am I in Granton?" When they shook their heads and said "No, hen," I would enquire, "Do you know where it is?" Everyone had an answer; it was just that their opinions did not tally. In the end I collated the replies and results of my research and drew my own map using pencils and ink on an old roll of wallpaper. Then I mounted it in an exhibition at Granton Hub, the local community centre, to prompt further discussion.

Granton Map by Tamsin Grainger. Pencils and ink on wallpaper. March 2025

Like most cartographers, I used a bird's eye street-view, and influenced by the ancient maps I had lying around my studio, I surrounded it with illustrations of other-than-humans I had met on my walks. The red admiral butterfly is shown in various stages of its development with the nettles and buddleia it thrives on. Our resident heron is there, together with a pair of oystercatchers from the Bay, and also the Wheatley Elm from my garden. This particular elm tree is ideal for Granton for it can cope with salt and high winds.

One chilly day in April, on a community walk, we stopped outside the gates of Caroline House, a private residence down by the sea that dated from 1585. A group member told us a ghost story associated with it: An overnight caretaker had made his rounds in the early evening, checking no-one else was present. All night he heard the distinct sound of furniture being moved upstairs and could not sleep. When someone came to relieve him the next morning, they went up to the floor above only to find that nothing had changed. It has never been explained and people love to speculate. While I was listening, I spied a fountain of water through the fence, coming out of a grassy knoll. What was its name? No-one knew.

As the months went by, my walks skirted around this property. I discovered that a drain on the side of the Firth of Forth regularly overflowed with Spring rains, flooding the road as if the water was making a dash for the Brick Beach, a nearby strand dumped with building materials. When I explored the beach, I found what looked like a cast-iron pipeline in the sand, half hidden by seaweed. Could it be spilling out water, and if so, where did it come from? My appetite truly wetted, I retraced my steps, hesitating at the gravelly side-entrance to Caroline House and peering into the gardens before creeping in undetected.

I found a burn pouring over a stone sill and rushing under a low-arched bridge. It flowed beside the house and, further on, at the bottom of some rickety steps. Slipping on the slimy wood, I clutched the handrail to save myself and, at a tilt, was delighted to spy a colony of over-wintering ladybirds all cuddled up close in a nook underneath. Following the water's flow, I came to the end of the garden and what looked like gate posts. Two square stacks of red stone were set into a wall glowing in the evening sun. Though the space between the stacks was bricked up, I could climb up and see the Brick Beach beyond. Turning to make my way back up the slope, I was assailed by angry cries. I had been discovered.

I offered profuse apologies and gently persuaded the owner I was not threatening. I felt she really wanted to tell me about the history of her home. "This is the Sea Gate and that is the Granton Burn," she told me. I was very happy to hear it, and asked, "Do you know where the source is?" I had recently walked the Braid Burn from its Portobello mouth, further along the Edinburgh coast, to the source in the Pentlands (my writing is part of an Art Walk Porty publication here). I assumed the Granton Burn must also originate there. "No," she replied, "I think it rises on Corstorphine Hill."

Corstorphone Hill, the Scott Tower

The owner let me out through the front entrance, and waved goodbye. I noticed how squelchy the grass was underfoot. In fact, it was always sodden here whatever the weather. Staying with the juicy noise, I passed the Scottish Gas building and the lights were on. Shut for quite a few years, I could see a security guard at the reception desk, so smiled and gestured. He let me in. "We're getting ready to re-open after the flood" he said, and I remembered that an inundation had been responsible for staff leaving; the Burn must run underneath. I continued on towards Forthquarter Park where there is a man-made canal and a new sign had been put up since my last visit: 'Please Look After Your Granton Burn.'

During the summer, I took more walks through Forthquarter Park, watching the moorhens negotiate the bullrushes and proud-necked swans swimming amongst irises. Silver birches were coming into full trembling leaf and gulls were lined up on the railings. A 'Footpath' marker pointed me between Waterfront Park and West Granton Road, and there was an unexpected lochan of sparkling water with a warning — 'Deep, Beware.'

After this, the trail went dry.

As Autumn began, I received an invitation to speak at the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust (SHBT) Winter Lecture Series on the Edinburgh Coastline. This was the excuse I needed to pick up my project again. I visited the National Library's wonderful map store and scoured for water sources. With the support of the librarians, I found wells and springs, sluices, another reservoir, and filtering beds, all between Corstorphine Hill and Caroline House. That weekend I put on my walking boots, took a bus to the foot of the hill and started to search for the origin of the Granton Burn. I believed it had served many of the industries I knew proliferated along the Forth Estuary in the 18th and 19th centuries: paper, coal, steel wire, and ink, to name a few.

The Granton Burn in the grounds of Caroline House

Starting up the zoo side, I quizzed a dog walker for signs of the burn. We were standing beside a Scottish Water unit which was buzzing and humming. "Oh yes," she said, "there are wells just on the other side of the Scott Tower." After locating them inside circular pens overgrown with brambles, it was easy to follow a gully in the undergrowth. I ignored my scribbled maps and almost flew down the hillside knowing I was onto something.

When I came to a road and stopped to get my bearings, rain was starting to drip onto my notebook and phone. Something else was wrong too: trying to align myself with Caroline House seemed to be impossible. I was not on the right side of the hill. It looked likely that I had been lured by a different burn altogether, one that was running towards Crammond Island, also on the Firth of Forth, but nearer the famous bridges. River though it must have been, this was not the one I was searching for.

Back up the steep incline I trudged, meeting a helpful woman with a baby strapped to her front who took me home to consult her husband. He gave me a paper map, but it did not mention the burn. Later, I spotted a man in a sodden anorak looking up and asked him if he knew the area. He said he was a tree surveyor and after a short explanation of my quest, explained that he was born in Granton and his father still lived there. "The Wardie Burn runs under his garden. If you stand outside the Co-op on Boswall Parkway after the rain you can hear it."

Back at the apex of the hill, I was fed up. It was four hours since I had arrived and according to the street map, it would take me the same time to get back home. Perhaps it was impossible to detect water below ground, even if I had spent a lot of time in its company. I ate my picnic and looked around. The land dropped steeply off to the left where the vegetation was lush. I got out the map I had sketched at home and it showed squiggly blue lines at the bottom where the old maps said Craigcrook Castle used to be. There had been a pump and it was definitely facing in the right direction. I had nothing to lose.

It was raining hard and the daylight would not last long. As I descended the steps, there seemed to be a watery flow in the earth — or was I imagining it? Through the fence, the grass flattened out and a horse was grazing. Suddenly, I stumbled into a hole, nearly falling forwards onto my hands and knees. Clear water was running over my feet; water with vitality. I waded on, energised now, despite soaking socks. It was as if I could feel a sort of magnetic pull from underneath. I sprang from bank to bank over a ditch, lost the trail but was able to find it again quickly. Water-loving plants and grasses, damp-loving fungi, the outward signs were clear, and inside I had a strong feeling too. I had a sense of the water being grateful. It seemed weird, but it really was as if the burn was wanting to be found, was glad to be beside me.

Onwards, and sometimes there was a path and sometimes none. It was unfamiliar territory, but I was not lost. Every time I looked at the compass, I was on-course. I passed a pool, a little creek, went behind a school and out of trees through back gardens. A lane led to a side-street and a main road and then I was in built-up Blackhall where men were on their way to the mosque. As daylight began to dwindle, I was still heading for the known sections when I crossed the familiar Roseburn Cycle Path, realising with surprise that I had never thought to look for a Rose Burn, if there was one*. Manoeuvring between bungalows and blandly designed housing schemes with not a lawn in sight, I kept my attention below ground.

After Pennywell, I came across Granton Mill, a development where a friend lives. In 2024, I had worked at the local history archive. No-one had known if there had been an actual mill there, nor which water it relied on if there was. Now I knew. I crossed Ferry Road into Granton, and trekked through the last blocks of nondescript tenement flats before regaining the reservoir. Ten minutes later I was on the sea side of Caroline House. It was no surprise to hear the force of the burn before I saw it, gushing along after the heavy rain.

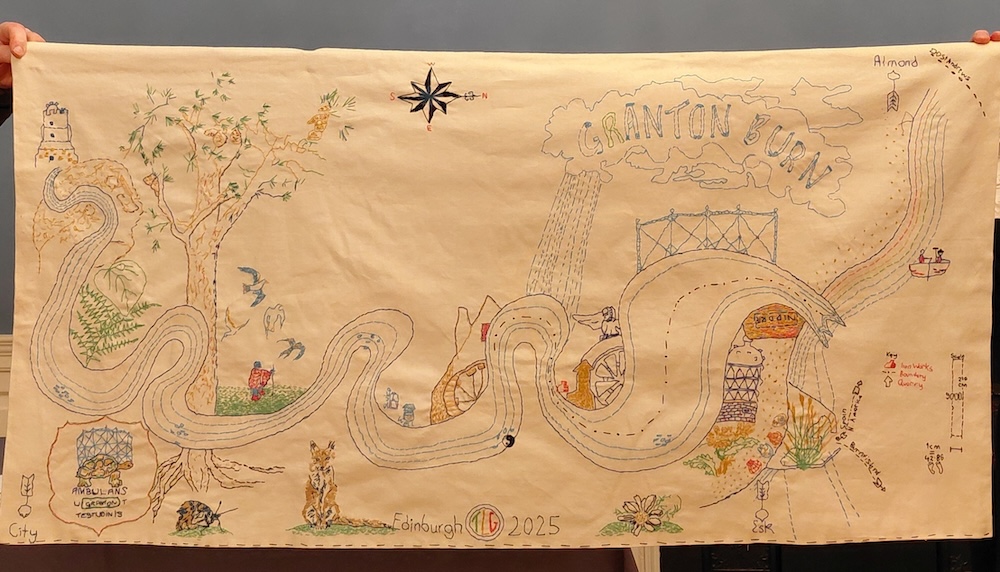

As I write, it is the last day of December. I know now that most of the Granton Burn is underground, as many urban rivers — the Fleet in London, Farset in Belfast, for example — are. May East, international urbanist and author of What if Women Designed the City? advises us not to rely on old maps when navigating changing urban landscapes. Prompted by this, and the difficulty I had finding the river, I have embroidered my own, its stitches representing my walking steps. Though this year's research has not been academically corroborated, this walk of faith seemed to be acknowledged by the Burn itself. As if it knew I was there and was pleased that I was paying it attention, it showed itself to me.

The Granton Burn, stitched map by Tamsin Grainger. Textile and cotton thread. December 2025

I chose to place the Burn at the forefront, and I matched the colours to the 1867 W. and A. K. Johnston Plan of Edinburgh and Leith, using simple running- and chain-stitches. It draws on my walking encounters, depicting a fox, a moth, chamomile, and oyster shells. There are also seabirds, tortoises, a pilgrim, and reminders of some of the industries that relied on the water. Presented at the SHBT Winter Series to accompany my lecture, From Hill to Sea, the map can be viewed at Riddles Court, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh.

*When I looked up the Rose Burn, I found that 'the burn drained into Corstorphine Loch, originally a glacial lake giving way to a large area of marshland which was finally drained in the c17th.' (Water of Leith Conservation Trust website)

*

Tamsin Grainger is a writer, bodyworker and walking artist living in Edinburgh. Visit her website here.

Another lovely edition from Cornwall's very own Ancient Magic Books.

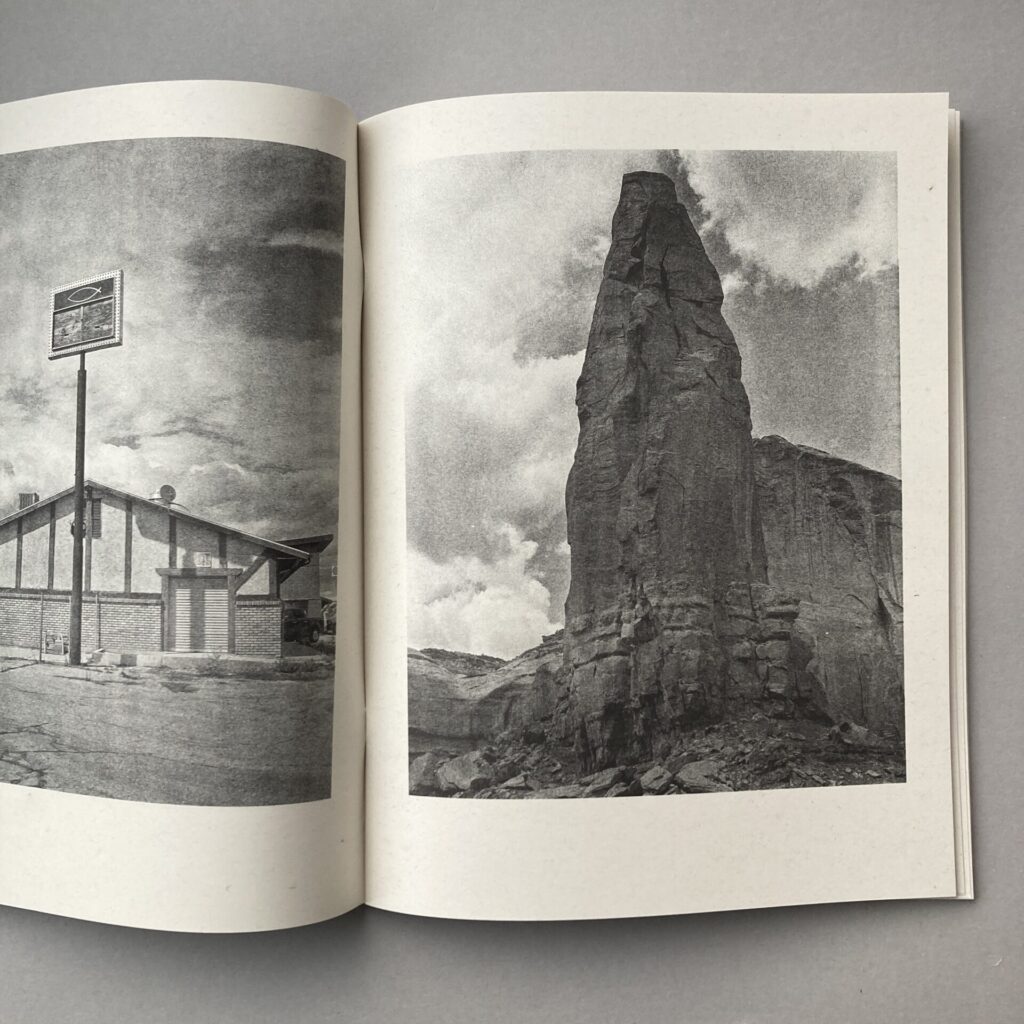

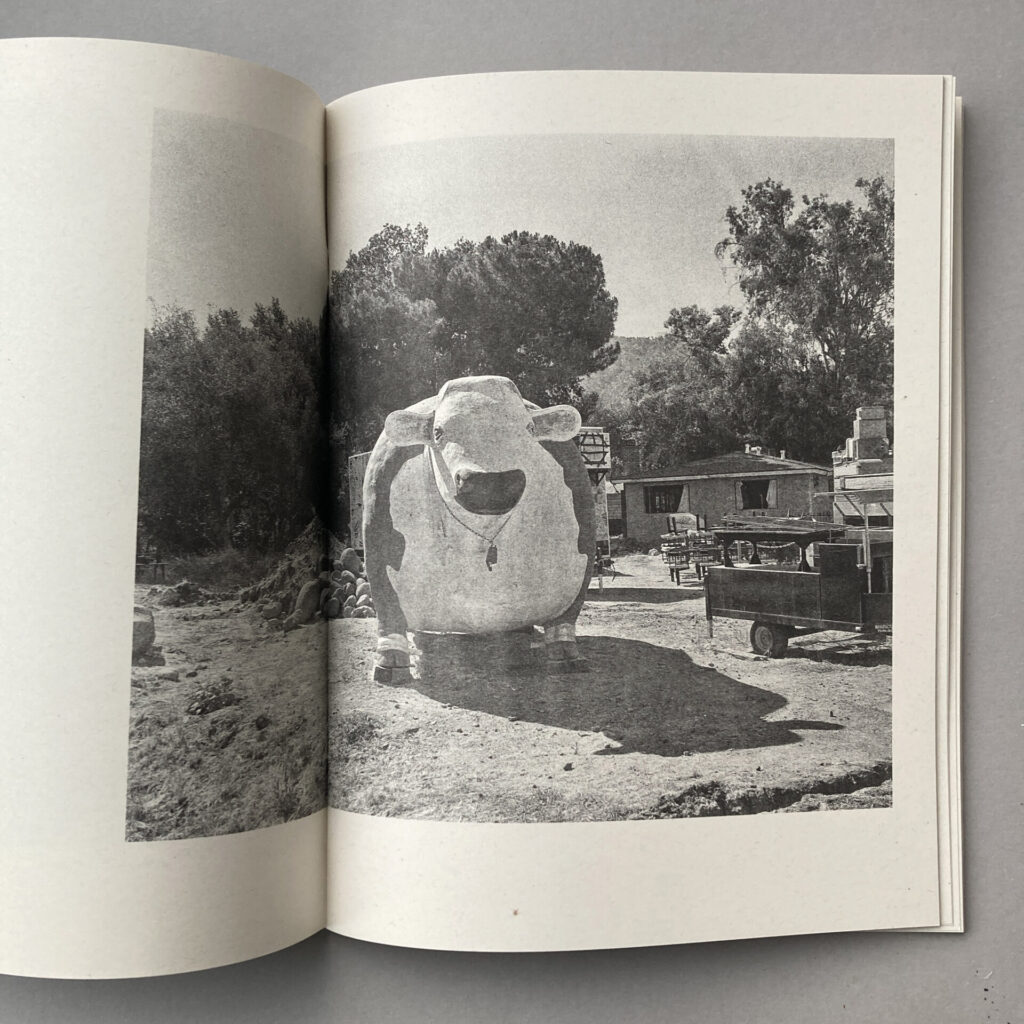

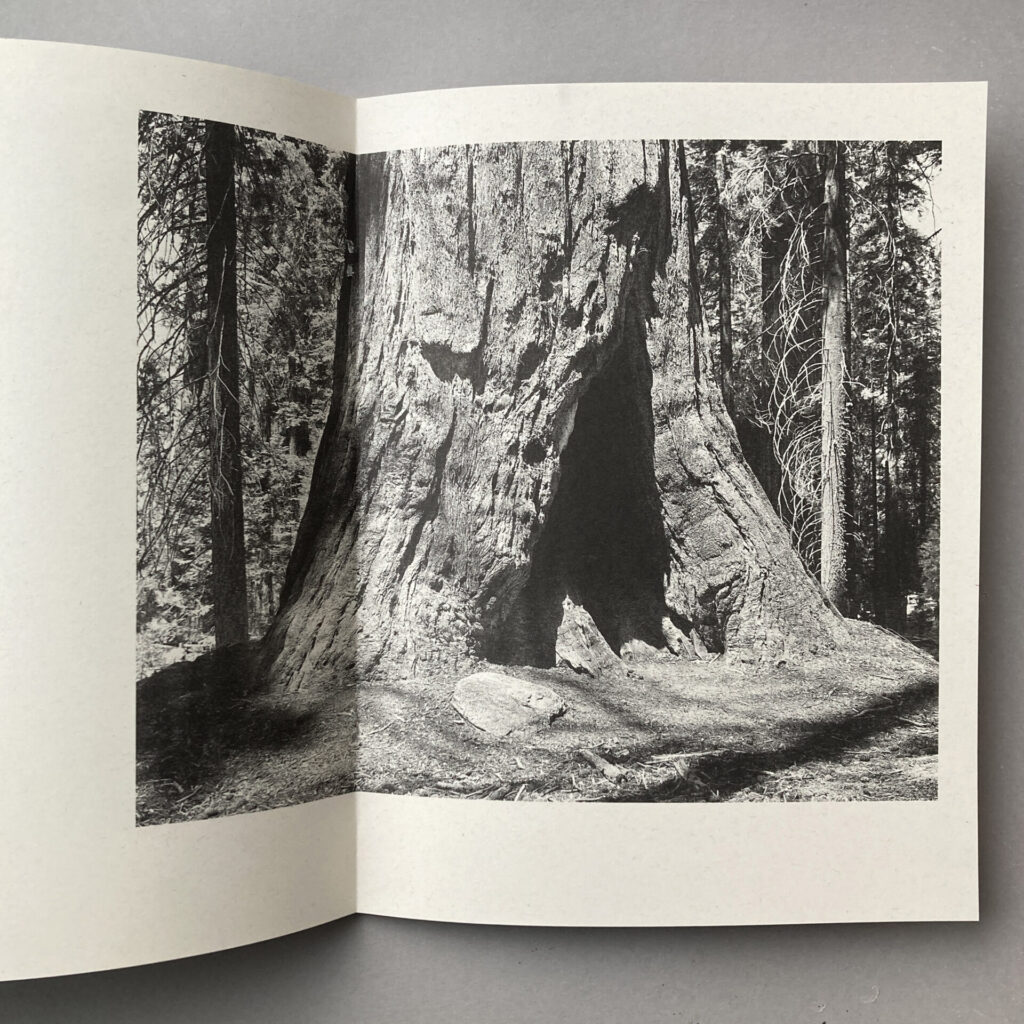

Taken in 2023 on a three week road trip around the West Coast of America, James Meredew's The Shady Motel & Other American Monuments is an offbeat, mostly people-less view of a tired-looking American landscape.

"I found it very strange how little people walked around the towns, it gave you an eery feeling every-time you entered a new place, I tried to capture some of that when walking around taking photos" - James Meredew

Risograph Printed

60 Pages

26x20cm

Context 135gsm Birch Recycled Inner Pages

Brown Craft Tape

Edition of 100

This book and all of its offcuts are 100% compostable

£16 and available here. We have also restocked some other Ancient Magic titles — An Daras / Portals by Rosie Kliskey (inspired by the ancient landscape of West Penwith in Cornwall) and West ~ A Cornish Surf Anthology by Pete Geall (an invitation to step into the world of spirited local surf scene in West Cornwall).

Splann!

Kevin Parr on a 2025 of high winds and topsy-turvy seasons.

It was a Sunday morning in mid-November when autumn finally broke. A jet-stream flicker brought an Arctic shove, behind which rose a periwinkle sky and low sun streaming through the French windows. The cyclonic cycle had been welcome when it broke the summer drought but then lingered too long. It wasn't that someone had left the tap running, more that they'd left the immersion on, steaming up the mirrors and thickening the soup. We were lighting the fire to dry the washing and fight the damp, sitting in t-shirts while outside the cloud rolled up from Chesil like smoke billowing from a bonfire of damp leaves.

We were back in the limbo of summer, only without the sun. Waiting once more for the shift — but what to do while we wait? The ox-eye daisies decided to come back into flower, while the frogs returned to the little pond by the garden gate. At night, they croaked in conversation as though it was early spring, while inside we struggled for sleep, lying beneath a sheet in November, our duvet that hug of cloud outside the window.

I was missing my routine, the ritual of walks that I tread each autumn. I particularly love the seasonal shift in the meadows at Kingcombe. There, in early September, small coppers and common blues still dance across the yarrow and knapweed, the leaves on the oaks only just beginning to brown. The change, week on week, is as smooth and inevitable as the diminishing arc of the sun. The pattern is reassuring, as flowers fade so waxcaps begin to glow among the green. There comes the vast ring of parasols in New Grafs Meadow and the steadily emergent skeleton of the single oak in Redholm. This year, though, went topsy-turvey. An early flush of fungi folded in the damp warmth, ceding to a churn of buttercups and dandelions. The grasses plumped and greened and the scorched soil saturated. In Redholm, the parasols sunk into oily dollops, while in the garden a blackbird joined the song thrush in full song.

***

The break brought frost and fieldfare as the soup cleared to consommé and steam curled off the backs of the cows. I was back in The Cairngorms, in the summer before this one, wondering if I was actually breathing or whether the air was so pure that it simply seeped through my pores. On the Monday, I walked the meadows until they dissolved into the dusk, crunching though the shadows and savouring the still. Autumn arrived abruptly, yet I was able to absorb the essence in a single afternoon. Just in time for the first bite of winter that followed later that week, though we avoided the snow of elsewhere.

A fortnight on and we are back into the cyclonic cycle, sitting once more in a t-shirt as Storm Bram batters the windows and floods the lanes. And what I must not do is long again for the break. It is a response incompatible with contentment, and little wonder that so many of us are wondering where the year went — we wished a lot of it away.

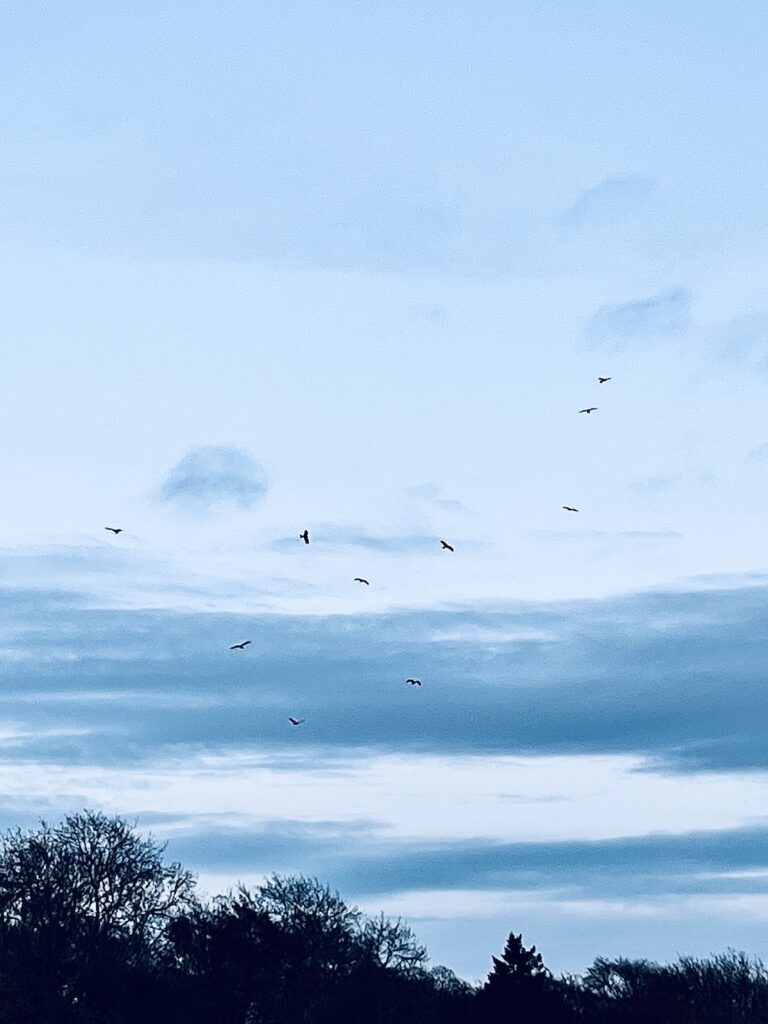

I am one of those people who struggles with change, although sometimes come those moments that remind us that change doesn't have to be bad. It was the Wednesday following my Monday meadowland walk, and Sue and I were sitting in the lounge as the world drifted outside the windows. The wind, though light, still came from the north and was pushing up the ridge opposite, giving perfect lift for the ravens to ride. Then came the sighting we've been expecting for several years. 'What is that?' Sue asked, although we both knew the answer. Our minds still worked through the process of probability before rationality brought confirmation. It couldn't be anything else.

G818, I later learned, a female white-tailed eagle that fledged in 2021. Some people dismiss the Isle of Wight released birds as 'plastic', but there was nothing artificial about my emotions in the then and there. Yes, I'll asterisk the sighting in my notebook, (species number 101 on the garden list), but I'll never forget the moment.

Dexter Petley reflects on the year his field became a forest.

Put simply, 2025 has been the year during which my field became a forest. Hec est finalis Concordia.

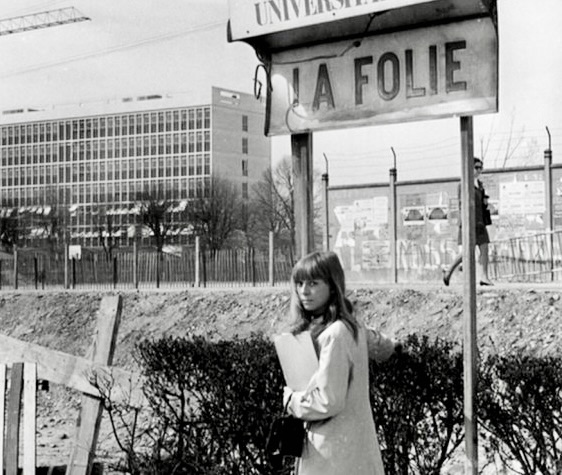

This new forest is not on parchment or in the feet of fines. It is not a forest because of the trees. Arboriculturists, I should add for veracity, might argue the terms and stages of succession, that it is only a forest at the first tree felled. Purchased as naked agricultural flood pasture in 2010, its one dead ash stump sat in bramble fester, seven oaks lined the lane, a straggle of goat willow and hazel shoots sporadic along the nettle boundary, an aquifer one yard underground, according to the water diviner. Not a lot to go on, though homeward bound. It even had a topographical name from 1077, La Folie, feulliée, fullie, foille, folie, a shelter of leaves.

Technically cued to become an ecotone, I dislike the term, my palimpsest was nonetheless a transitional zone between two different habitats. The idea was for the eventual presence of both species and features from bordering habitats. Though triangular, I counted four; two forest, one pasture, one tillage.

From the beginning, it was out of my hands. By its second summer the farmer said it was too woody to cut for hay. Pioneer saplings were arriving from the mother forest either side. At one end, the potager struggled then sank in soaked clay and marsh grass. At the other I hoisted camo nets to conceal my illegal home from any passing collaborator. La Folie, also a cabane, or maison de campagne. I need not have worried. Today, even the Google plane cannot spot the yurt.

My first autumn act of 2010 was to plant a twenty-six-tree orchard of mixed fruit. Each tree hole filled with brown water as I dug them, months after the first garden crops had already rotted in the ground. La Folie, according to Le Robert, dictionnaire historique de la langue française, poor ground only a madman would cultivate. For years the saplings stunted at competition level, the campagnoles and musaraignes stripped their bark until, when finally they struggled into flower one spring, they'd reverted to their root stocks, mostly gender-neutral prunes. Good cherry, pears and apples, plums and greengages floundering in no mans land.

In the intervening years, the jays chipped in to save the day. By their raucous meanderings, bombing acorns hither and thither, the one-by-one became thousands. Stubby oaks rose above the height of rye grass and marsh thistle. The winds supplied the rest. Aspens and ash, hazel and willow, beach, hornbeam and gean, all spreading in moonlight, until this year the fruit trees, deciduous and mycelium became one place, habitat united, 3-in-1, a forest garden as I sat and watched. Neither Weald nor Anderida of my roots, just the coincidence of joined hands, my triangular hectare and a spit is now the meeting place for the offspring of old forest pushed in from either side. Naturally aspirated, seen from the air or the ground, a young forest not because of trees, which do not on their own make a forest, but because of the mushrooms.

This summer, they came, these mycological migrants, in their thousands, in rings and rows, ranks and in reams. At first, they seemed to map the animal passages, having come by hoof and claw from three sides, few edible species yet, just their harbingers and precursors, the edibles spored-in for the next rise, or the next. The mousseron, though technically a field species, showed up in both spring and autumn variant. Both were eaten to ritual, as blood-of-ground in a kind of coming-of-age omelette. And among the aspens, now trembling with anticipation, the true heralds of boletus, the fly agarics, up and at 'em, leaving their message poste restante. Cortinaires and pholiotes, lactaires and hygrophores, the latter at the first frosts, edible if mediocre. The fruit trees shared the evolution of good news. Dishevelled and unpruned, they flashed a show of April blossom which could only mean trouble come harvest. The orchard, having decided to fruit after 15 sterile autumns, was invisible once the blossom died, oaked-in and brambled over. Having witnessed this march of mushrooms and the blossom revival, I cleared a passage for the miracle as best I could. Though genus unconfirmed, they poured their summer hearts out into multi-coloured balls which bent the branches and filled the baskets.

Plums of a kind, mirabelles and greengages, apples and pears, wasps, hornets and pine martens in contention for the final. We picked and bottled and jarred, stuffed, swatted, spat and composted, like spenders at a jackpot. The hornets, sensing an end to famine, stayed until the end, making caves of the late Calvilles still on the tree, relinquished only at the first November frosts.

In these frosts I linger still, reluctant to pack down the outside kitchen, beside which hangs an old, enamelled metal sign with red lettering, LA FOLIE, once the name-plaque on a railway station platform. Somehow, through that mysterious passage of hands, it came to me this year, La Folie, an extravagant or dispendieuse construction. This modest sign, from the factory of Laborde, est.1900, merits personification for its place of witness, the times it saw, and those who saw it. Indeed, what's in a name? La Folie, a stone's throw from the Seine, was in 1690 a rich maison de plaisance, with all it implies, of boudoirs and alcoves and demi-mondaines. Underground, great caverns were created from mining the stone which built half of Paris. In 1809, La Folie became a factory producing chemicals. In 1837, a railway halt on the first line out of Paris. In 1900 the caves were rented to a champignonniste who produced the famous mushroom of Paris. An early camp d'aviation, La Folie in 1916 became a vital base where biplanes were stocked and repaired. In the Second World War the Camp de La Folie became Beutepark Luftwaffe n° 5 Nanterre, storage depot for Luftwaffe wrecks arriving by train, spare parts workshop, a black museum for shot-down allied planes dismantled for scrutiny in the laboratory of war. Swords into ploughshares, my enamelled plaque was still there on the post-war aero club platform when they built the University of Nanterre beside it. Perhaps torn down by students in the riots of 1968, La Folie being the very place where that whole thing began, or sold to a collector in 1972 when the station was rebuilt. In 2025, this old sign has been restored to camp, and the folly, also the madness, has been vindicated.

As daylight shrinks and the sun barely skirts the ground, the solar holds by touch and go, by twists and turns. Electricity is rationed to an hour per day, the power station tops the vital services, charging the fridge battery or laptop, bread dough mixer or electric bike, depending upon the weather or the task at hand. My old carp fishing barrow has converted to a mobile station, solar panel, battery and invertor, a constant standby which I wheel around the forest field as the sun pokes feebly into clearings, mostly just to keep a lamp lit above the stove. In August, the 1000 litre rain tank filled to its brim, now shut off and sealed with clean water, enough at 5 litres per week, my average total consumption, to last till doomsday. Coffee water comes from a spring in a nearby forest, the Fountain of Madame Jeanne, born 1378, daughter of Pierre II, the Comte d'Alençon. The spring was discovered by local monks in 1170 and reputed for its therapeutic properties. My old neighbour's father, a farmer, would cycle to the fountain every morning during the war to fill the baby's feeding bottles. Now just a bramble covered path, a plastic pipe sticks from a bank as water gushes into a gravel pool lined in brick, its 1880s thatched shelter a fenced off ruin, the thatch strewn in rough hanks along the path.

The point, it seems, of 2025, has been to complete that vision I had thirty years ago, of how life could be lived, by rain, and sun, and wood, by joined up history, wits and luck, risk and caution, sacrifice, even piety in the brunt of natural calamity, simplicity the overwhelming bounty, for in truth it's also been about how to live on a third of the minimum wage, the neglected writer's annuity, how nature pays your rent, fills your kettle, heats your free water. Poverty at its best, the woodshed full of logs from La Folie, the caravan-cum-pantry stocked with canning jars of La Folie, its cèpes and trompettes, green beans and born-again fruit. The palimpsest becomes botanical and bestiary, that old tin sign now turned the other way, from looking on at violence to face the sagacity of trees.

Ian Preece shares another year in books, records, film, life and community.

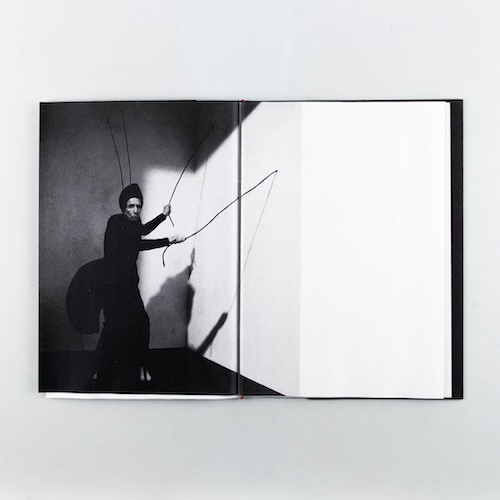

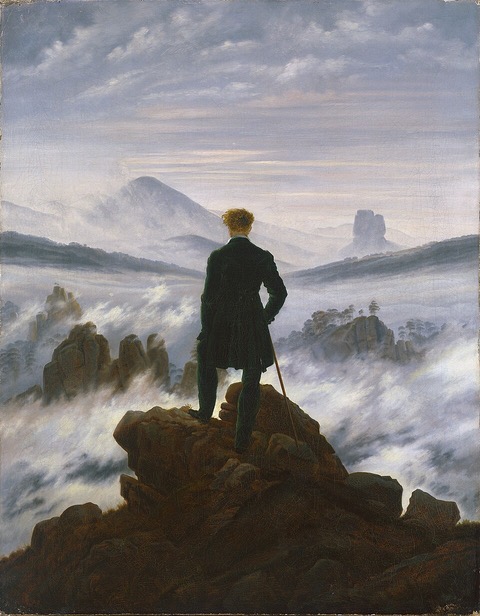

I think, as I get older, I'm just on a simple path in life now: to strip out all the crap, all the artifice. I managed to catch at the NFT this year, on a super-beautiful 35mm colour print, a screening of what's possibly my favourite film of all time: Claire Denis' 35 Shots of Rum (or 35 Rhums in the French). First released in 2008, it's a kind of simple tale of a train driver in Paris (played by Alex Descas, a Denis staple) and his daughter (Mati Diop), who's about to spread her wings. There's lingering ennui, melancholy, unrequited longings, the passing of time, and the simple matter of getting by, day to day, on the rainy twilight streets of a Parisian banlieue; a mise en scène superficially gloomy but full of hope, and soundtracked (like all Denis' films) with commensurate aplomb by the Tindersticks, which also includes what has to be the greatest (and most fraught) use of 'Nightshift' by the Commodores ever captured on celluloid. It's the fans of understatement's most understated film. I've been searching for that bottled essence on the silver screen ever since, but it's proved elusive (Paterson, Perfect Days, Past Lives, Shadows in Paradise, Winter in Sokcho - close; What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? ‒ also close, but too whimsical; The Holdovers - sharp lines and superb acting, held back by dollops of Hollywood cheese; The Mastermind ‒ disappointingly flat, all super-cool cars and cinematography, though an unengaging lead untypical of Kelly Reichardt movies renders it not quite the measure of its brilliant Rob Mazurek soundtrack; La Cocina - great, more than a tad theatrical though; Denis' own Trouble in Mind - similar palette, superb matching soundtrack, but too psychotic). I probably need to work my way back to Yasujirō Ozu's Late Spring.

Is it me, or is everything over-produced, over-hyped, suspect, lurching to the false, or just downright fake these days? On one level there's obvious questions like: isn't Venezuelan oil Venezuelan? Or shouldn't a manager familiar with life on the touchline be allowed to run a football club (rather than someone who was once a winger, or founded a talent agency from the back bedroom of their mum's house before making a killing on the futures markets)? On a more micro level, we live in an over-mediated world: 6 Music DJs and trailers carry on like they are all our best mates accompanying us on our own personal 'journeys in sound' ('shout out to Maya and Felix baking cranberry muffins with their dad in Swanley, Kent'; with, of course, the honourable exception of Gideon Coe, who actually is someone listeners would queue round the block to have a pint with); the Guardian want us to 'share our experience'; and 'this is our BBC', for 'each of us'. Why is there a 'severe weather warning' and news bulletin on the weather page of my phone from the Sun proclaiming 'snow in London' when out of the window the sun dazzles in a clear blue sky and there's just a very slight firmness under foot from a light frost? Why this desperate faux inclusivity when this feels like a time when people are more divided than ever? The answer, I guess, is the same as it ever was: the smokescreens, filters, buffers and diversionary tactics of 'late' (it's always 'late'?) capitalism. Fifteen years late to the party, I read John Lanchester's Whoops! just before Christmas, explaining the financial crash of 2008 to finance-illiterate idiots like me: he was on the money re. the monetization of every last walk of everyday life; and I think I buy his overreaching thesis that now communism is dead and buried in the east, capitalism no longer has to pretend to be benevolent in terms of the greater good in the west (no more education, welfare, infrastructural spending for the mass 'we'), the untethered banking madness leading up to 2008 (super high-interest subprime loans earning bankers a fortune ahead of them reaping a further payout/bailout/fortune from taxpayers) signaling just the start of a new rapacious world order curated for the entitled few.

Fuck that. Highlights of 2025 have included Wassie One at new reggae night 'People's Choice' in the Plough & Harrow in Leytonstone (it was a lady called Sandra's birthday - she cut up a large chocolate cake and handed rounded slices in polystyrene bowls to everyone, friends and strangers alike); joining the Polytechnic of Wales WhatsApp group for the BA Communication Studies alumni, intake of 1985, then meeting folk I hadn't seen for 37 years on a lovely weekend at Gareth's house in Dorset, everyone chipping in, cooking, washing up, walking on the beach, playing table tennis and catching up with more chilled, older versions of ourselves after four decades of life; then, as a direct spin-off of that, dancing to A. Skillz's 'California Soul' in a fog of lazers and dry ice in a basement in Dalston at Helene's 60th birthday party that has now passed into legend; listening to speakers talking about the inclusivity of their community on a keep-Stephen Christopher Yaxley-Lennon (let's stick to real names)-and-his-thugs-out-of-Whitechapel march (plus a fine dahl, roti and tea afterwards in a café by the tube station with my mate Wayne); checking out the rooftops, swimming spots and environs of Marseille; DJing with Doug of the Sir Douglas Sound Hi-Fi, loading Doug's periscopic speaker and decks in and out of the van and into various south-east London pubs, then spinning tunes from the likes of Al Campbell, the Morewells, More Relation, The Invaders and Phyllis Dillon. Doug has been heavily involved in a local musicians' open mic night, set up and ran a poetry and spoken-word night, facilitated our services as a support act to The Brockalites, and soundtracked plenty of pubs' Friday and Saturday evenings in SE23: exemplary use of a wide-angled lens; selfless community service of the highest order.

*

'I love a circular conversation,' as the late, great, sadly missed John Broad/Johnny Green used to say at the end of a phone call. Just to circle back to French railways, Mattia Filice's Driver (nyrb) is a life-affirming book, a free-verse novel based on Filice's two decades as driver on French railways, much of it in the Paris region. I'd be bullshitting if I said I got every reference or allusion to Rimbaud, Congolese French rappers, suburban railway stations, inner diesel and electric workings or Apollinaire poems, but I love all the smoking in the cab, the quotidian dramas, the endless tussle with management, the Socratic asides and existential crises that arise staring at miles and miles of steel rails unfurling before you on misty mornings and dark nights, the slowly accruing sense of solidarity and friendship among the drivers in Filice's intake. Jacques Houis' translation is beautifully musical: at various points Filice compares the tempo of the train running over the crossties to Tommy Flanagan's piano on John Coltrane's 'Giant Steps', alludes to the pantograph and the train itself as like the bow of a cello scraping against the strings of the catenary wires, and writes superbly with a cabin-eye view. Here he is on a morning commuter train, deciding whether to pull out from the platform on time: 'I think I'm God, master of the doors . . . To those who run, who pant in protest at their sad fate, I reopen the doors. Some mortals are aware and give thanks through the camera, others ignore me and put their faith in providence . . . To those who drag their feet I'm pitiless. In my kingdom, one's place has to be earned.' Right on; chapeau.

*

Mixtape 2025

1 Rafael Toral, 'Take the A Train'. I've got slightly obsessed with this D-side, bonus vinyl track, which takes a while to bloom into life, but when it does, does so magnificently: a glorious stretched-out blare of the main riff of the Billy Strayhorn/Duke Ellington classic of yore. The rest of the experimental Portuguese guitarist's album Traveling Light is similarly made up of elongated, languorous jazz chords ‒ especially beautiful are the versions Billie Holiday's 'Body and Soul' and the Chet Baker/John Coltrane/Don Raye standard 'You Don't Know What Love is'. 'Lovingly valve saturated strums, bent by Toral's whammy' is the fine description on Boomkat. Album of the year.

2 أحمد [Ahmed] 'Isma'a [Listen]'. In truth I've listened to Ahmed Abdul-Malik's 'Summertime' from his sublime 1963 LP The Eastern Moods of Ahmed Abdul-Malik far more than I have the modern day أحمد [Ahmed]'s furious deconstructions of the Brooklyn bebop bassist and oud player on their own Wood Blues or Giant Beauty. But this year I finally caught أحمد [Ahmed] live at Café Oto. That gig smoked. Antonin Gerbal's pulsing, skittering skins; Seymour Wright's horn sparking into the darkness; Pat Thomas's clangorous piano blues; Joel Grip's pounding bass . . . what could have been a relentless hammering was an ecstatic journey that gently descended to smouldering embers.

3 Nicole Hale, 'All My Friends', 'Give it Time', 'Sleeping Dogs' (from the Curly Tapes cassette Some Kind of Longing). This tape has been stuck in my deck all year. It's a languorous but poised, beautifully smoky thing. Opening track 'All My Friends' unfurls and fills out slowly like the morning light. Some of these melodies might feel hazily familiar from 1970s FM radio, filtered through a Mazzy Star-like (even a more somnolent Big Star-like) gauze. There's early Jolie Holland in there too, but Hale's take is all her own - she's listed as playing 'keys, guitars, vocals and skateboard'. I got so obsessed with the track 'Give it Time' its lustre has dimmed slightly. New favourite these days is 'Sleeping Dogs', complete with spare, sleepy piano and, if listening on headphones, what sounds like a crackling distant storm, audio vérité not a million miles away from Sonic Youth's 'Providence, Rhode Island'.

4 Joe McPhee, 'Cosmic Love'. Talking of 1970s vibes, I bought this on 7-inch a few years back, but it's cropped up again as the closing track on a fine Corbett vs Dempsey compilation LP linked to a Sun Ra exhibition in the label's gallery in Chicago. Man, is this a beauty. I was DJing at a local writers' open-mic night in south-east London earlier this year and I tried to mix it in with 'Short Pieces' from McPhee's latest poetry/free noise opus on Smalltown Supersound (with Mats Gustafsson) and got the levels and timing all wrong: the rutly, strangulated raspy skronk in the middle of 'Cosmic Love' fused with the vacuum-cleaner feedback on the poetry LP. The speaker stack squalled, the pub cat shot out the door and a few poets grimaced. Just as beautifully coruscating is Straight Up, Without Wings: the Musical Flight of Joe McPhee (also published by Corbett vs Dempsey). There's a fantastic moment when a young McPhee, driving home from his late shift at the ball bearings factory outside Poughkeepsie where he worked for years, first hears John Coltrane's 'Chasin' the Train' on the car radio at 2 in the morning: 'I went beserk. I pulled up in front of my house, the windows of the car were open and the radio was blaring. The sound was extreme. I couldn't contain myself. I went crazy . . . screaming and going on. My father heard the sound of the radio and me screaming, and thought I was insane. I was, but that's another story.' I just listened to 'Cosmic Love' again, and after all these plays hadn't realized right at the end, just as McPhee's space organ fades, you can just make out ocean waves crashing against the shore.

5 Zoh Amba, 'Fruit Gathering'/'Ma'. Haunting, mournful moments of quiet Ayleresque beauty from Zoh Amba's excellent new Sun LP.

6 Mike Polizze, 'It Goes Without Saying'. From Polizze's dreamy Around Sound LP this track lodged in my head for much of the summer; kind of acoustic J. Mascis with mellotron and vibraphone fuzz.

7 Phyllis Dillon, 'You're Like Heaven to Me'. Just an exquisite 2 mins 04 seconds from 1972, reissued as a Duke Reid 7-inch.

8 The Invaders, 'Give Jah the Glory'. Beautiful upfull reggae vibes from archive LP of the year, Floating Around the Sun, which should be in every home, and also includes Invaders' gems 'Conquering Lion' and 'Heaven & Earth'.

9 Al Campbell 'Babylon'. In the sleevenotes to the 2000 Pressure Sounds Phil Pratt Thing compilation, Harry Hawke noted, 'When Phil first took Al Campbell to the recording studio many observers apparently laughed at him saying that Al "couldn't sing"! Phil felt differently.' I knew there was a reason I love Al Campbell's singing. Give me his slightly flat, unique grain any day over the more honeyed tones of Ken Boothe, Alton Ellis and Delroy Wilson, et al. 'Babylon' is a Peckings' masterwork of smouldering intent: 'Babylon them a criminal/Babylon them an animal/Babylon them a conman/Babylon them a ginal'.

10 Yassokiiba, 'Dub 5'. Beautifully spacey, chilled-out digidub 7-inch from Tokyo; a heavenly muted steppa.

11 Mark Ernestus' Ndagga Rhythm Force, 'Lamp Fall'/'Dieuw Bakhul'. Rhythm & Sound's Berlin dubscapes rinsed through a Dakar filter. Hushed, spectral hypnotic vocal from Mbene Diatta Seck floats through Ernestus' slowly intensifying beats.

12 Mother Tongue, 'Djangaloma Dara'. Mola Sylla's windblown Senegalese blues refracted through jazzy Puerto Rican drummer Frank Rosaly and Dutch electric clavichord courtesy of Oscar Jan Hoogland. Slightly desolate but deeply funky too.

13 Melody & Bybit, 'Kwakaenda Imbwa'. Total heater from glorious comp Roots Rocking Zimbabwe: The Modern Sound of Harare Townships, 1975‒1980, written by Oliver Mtukudzi's sister Bybit, and featuring Oliver - a kind of lodestar for Samy Ben Redjeb's Analog Africa project - on lead vocals.

14 Pharoah Sanders, 'Ocean Song'. I spent too long stoned as a pigeon in my chalet at Pontins, Camber Sands (and in the heated swimming pool ‒ first time I'd been in one of those), and have only a dim memory of catching A Tribe Called Quest late at night on what I think was the first ever Jazz FM weekender, in November 1990. In my defence I was only 23, but to compound my dismay I've belatedly come to realise, after years of lamenting never catching Pharoah Sanders live, that he was on the bill at the holiday camp too. Fuck. Still catching up with his records - this beauty is from the Bill Laswell-produced LP Message from Home of a few years later, but Sanders' gorgeous saxophone melodies make me think of 1980s Crown Heights/Brooklyn/Manhattan, a world this émigré from the East Midlands had no idea about (just received images from the TV).

15 The Uniques, 'My Conversation'. Totally ace, lolloping late-1960s rocksteady, spun (I think) by Miss T in the Servant Jazz Quarters' basement at a recent Ram Jam night, and a fixture on our kitchen turntable over the festive period and ever since.

16 Jake Xerxes Fussell and James Elkington, 'Contemplating the Moon', 'Glow in the Dark' and 'County Z', from Music for Rebuilding, the elegiac, beautifully composed soundtrack to forthcoming Josh O'Connor film Rebuilding. This is serene, poignant Willy Vlautin/The Delines The Night Always Comes, William Tyler's First Cow and Bruce Langhorne's The Hired Hand territory. 'Things We Lost' concludes with a glorious muted brass finale (from Anna Jacobsen) that makes me well up every time (like Johann Johannson's The Miners' Hymns fifteen years on).

Sue Brooks celebrates more than 75 years in the company of Radio 4.

This is a celebration of more than 75 years with my faithful companion, Radio 4. It came to me so clearly when the BBC was under attack in early November. I leapt to its defence like a teacher watching a bully in the playground. How dare he? I must stand up and make a tribute of some sort, and here it is.

2025 was filled with anniversaries, some of which seem to have reached the papers and social media — 75 years of The Archers for example, although for myself that particular addiction didn't last long. I listened out for Pick Of The Year, usually by a special guest — not someone already associated with Radio 4. This year it was Jeanette Winterson and went out on Christmas Day, which felt auspicious. Generally it goes out at some point in the Christmas week, rarely on the Day itself. I looked at the rest of the schedule and felt that Radio 4 was standing up for itself magnificently. JUST LISTEN TO WHAT WE CAN DO.

Jeanette Winterson — a superb writer who turns out to be a lifelong fan of Radio 4. It was a selection after my own heart and I applauded mightily. A little chastened because it echoed my own ideas, but also thinking…there is so much more.

This year I have discovered two new series — Artworks (Radio 4's arts and culture documentaries, presented as a podcast) and Illuminated (Radio 4's home for creative and surprising one-off documentaries which shed light on hidden worlds). YES, those hidden worlds. Among them, I found 50 Years of the Koln Concert, a programme which commemorated the first 100 years of The Shipping Forecast, and the unforgettable Sea Like a Mirror, celebrating 220 years since Rear Admiral Francis Beaufort devised the Beaufort Scale for wind speeds. They have been feasts for the imagination, touching all the senses, in the way a dream does sometimes.

Do you have appetite for more? Perhaps two more, one of which I can't resist although it doesn't quite fit into the time frame. On This Cultural Life, John Wilson talks to a well-known artist about the inspirations behind their work. In July 2022 he interviewed Maggie Hambling. Magnifique alors, Maggie.

And the last, which has to be Melvyn. In his 86th year, he announced his retirement from In Our Time ( the "death slot" — 9am on Thursday mornings — as it was known in Radio 4 schedules many years ago). This unappealing title now has a vast (over 1,000 episodes) archive and a global audience of dedicated listeners.

Rather than choose a personal favourite, I thought I'd share the fifteen minute conversation between Melvyn and his successor Misha Glenny. It reminded me of the last interview with Dennis Potter, just before he died in 1994, aged 59. Melvyn and Dennis sharing their love of BBC Radio and TV. It's all there in Melvyn's own words.

The first In Our Time without him went out on January 15th. Let's wish Misha Glenny our VERY best…and a heartfelt HAPPY NEW YEAR for the BBC.

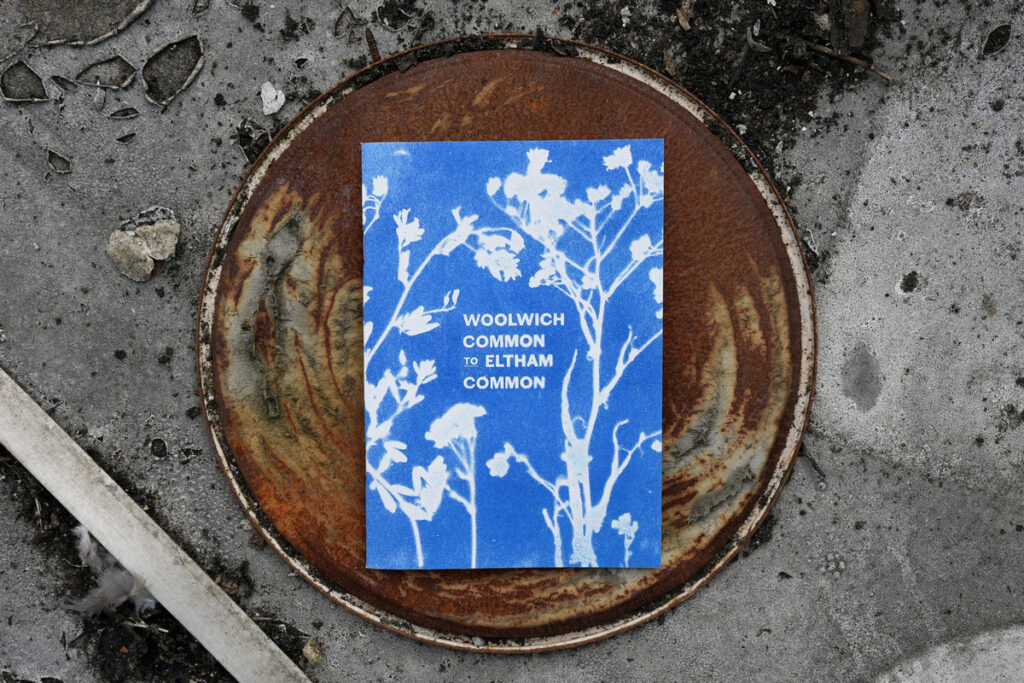

Back in stock just in time for Bandcamp Friday! A new run of the much-loved and previously out of print vol. 2 of South London Landscape History's South London Commons zines, focusing on Woolwich Common to Eltham Common.

Starting at Bostall Heath in the south-east and finishing at Putney Heath in the south-west, a chain of commons runs in a wide arc across the whole of South London.

This series of zines mixes history, ecology, psychogeography, architecture, poetry and memoir to unpack how, taken together, the commons provide the key to the South London landscape.

Written by landscape historian John Gray and featuring photographs by Woolwich-based photographer Sam Walton, this second zine in the series explores a pair of ancient commons. The cover is a cyanotype by artist Sally Gunnett, created using plants from Woolwich Common and evoking ancestral rights of common. The cyanotype was then Risograph printed by Lewisham's Page Masters, along with the rest of the publication.

CONTENTS: "How does landscape manifest as a system of memory?"—the topography of South London—Shooter's Hill—a love letter to Woolwich Common—walking its convoluted history—"part blasted heath, part great park"—Blue Danube—buried Blitz rubble—Nightingales in Woolwich—the house Bernadine Evaristo grew up in—echoes of imperialism inscribed in the landscape—colonial rabbits and colonial dogs—the South London Vernacular—the virtue of eclecticism out of the necessity of randomised destruction—Eltham Common and the old Dover Road—Kossowski's mural on the Old Kent Road, one of the jewels of South London—the common and the gallows—in defence of Mock Tudor—Peter Barber's Rochester Way: the best of contemporary architecture—the worst: Kidbrooke Village—not a place for walking free—Outer South London Vernacular, from Eltham to New Malden—an unremarkable scrap of grass.

Vol. 3 (One Tree Hill to Peckham Rye Common) is also still in stock!

Emma Warren contemplates 2025's dust — and slender but powerful rays of light.

I've had enough of the past. It's full of dust, and the only dust I want now is the kind you might see mote-floating in a ray of sunshine. You know, like on a slow and warm day when there's time to stop and look at the walls or to notice how the light is falling.

Rarer days, these days, when it's easier to get stuck scrolling, or in your head, or for your whole body to feel like you've constantly stuck your fingers into a source of bad electricity. These are all reasonable responses, given that the last twelve months followed the previous twelve months.

The point of reflecting is to see more clearly. So here are a handful of thoughts and observations based on Things That Happened over the last 365 days, articulated in attempt to reckon with reality and therefore find something approaching stability - or at least the beginnings of stability, which is surely based in knowing where you're at.

For me, looking back must also involve looking forward. Especially now, when one of the Things That Happened is the realisation that huge amounts of money and effort are being spent on division, often using tropes around land and belonging.

I'm asking myself a question here, which is unformed, but which circles around what you might call 'anti-fascist nature writing' although I don't know exactly what this would look like in practice. The Irish writer Manchán Magan, who died a few months ago, offered a suggestion. He described a realisation that his explorations of Irish language and its relationship to the land, Thirty Two Words For Field, could be co-opted by right wingers. And he decided that he could divert that risk by in his words 'evoking the divine feminine'.

It's not a question any of us can answer straight away. But I hope that by considering it, I'll be pointing in the right direction: away from the dust.

Flags is it?

I have a great deal of respect for the person who displayed this quote alongside colourful flags from a range of nations along the railings of a bridge in Pontllanfraith, Wales. My friend, who is staying with me as I write this, reminded me that as teenagers we would sandpaper swastikas off a wooden bridge near where she lived. Is it vandalism or civic duty to deface divisive signage?

Also, if people in England want to grapple with our apparently new and evidently widespread flag problem, then they could just look across the Irish sea. There are plenty of people in that part of the UK who know quite a lot about flags. John Hewitt (1907-1987) is mostly known as a nature poet, writing regularly about the Glens of Antrim, but his poems reckon equally with division, describing: 'creed-crazed zealots and the ignorant crowd / long-nurtured, never checked, in ways of hate.'

The poets of the past might also be able to help with some of our current conundrums. I take Hewitt to be saying: check hate - or it will check us all.

Connection is everything

Free dancefloors really do bring people together. I had spent a year working with The Southbank Centre on a whole-summer season based around my book Dance Your Way Home. The idea was to evoke and reflect a version of London I believe in, where everyone's from everywhere and where we're blessed with music, movement and culture from around the world.

King Original Sound would bring their own soundsystem. We'd have an Irish hooley; a knees-up to fiddle, flute and bodhrán. There would be a carefully curated afternoon event for people with chronic illness. And then, two weeks before the opening event, a major bereavement hit, affecting everyone I love the most. How could I even leave the house, let alone dance on the banks of the River Thames, under these circumstances?

I'd written Dance Your Way Home with an intention: that it would articulate the connective power of the dancefloor and that it would encourage hesitant or shy dancers to step onto the edges. These qualities could hold me too, and they did. Standing at the back, soaked in sound and facing the river, with fellow Londoners from every imaginable age group and background, helped bring me back together too.

'No such thing as innocent bystanding'

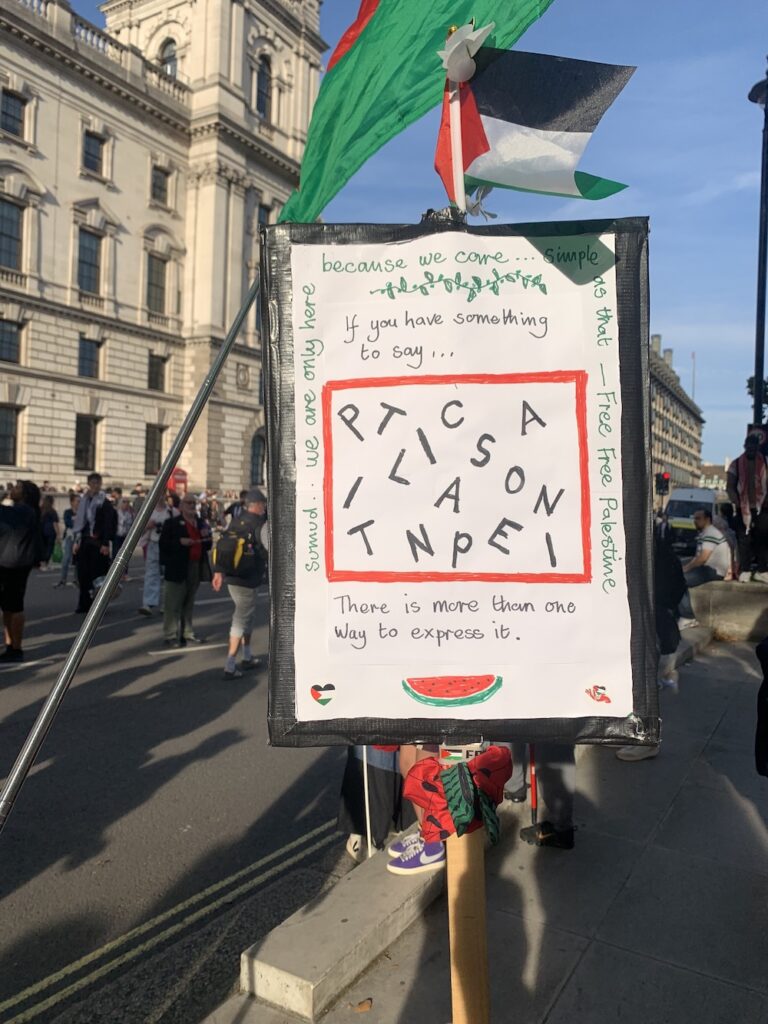

The words of another poet, Seamus Heaney, felt especially alive this summer. A friend I'd met whilst staying in the Curfew Tower in Cushendall quoted Heaney at me after seeing videos posted from a Palestine Action protest. I'd been there to witness, document, and report what I saw, which included the presence of Welsh police in Heddlu caps and PSNI officers from Northern Ireland alongside Met Police officers. The protests were, of course, in response to genocide in Gaza and to the proscription of Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation. The government response, enacted by the police, felt to me like a seismic shift. A long-established reality - the previously-ordinary act of holding a hand-made sign, communicating a widely-held view, at a protest - was disappearing in real time.

Standing outside Westminster Magistrates Court during Mo Chara's repeated court dates I observed different energies. The pavement became a back-room session, with crowd singalongs of 'Eileen Óg', 'The Fields of Athenry' and The Cranberries' 'Zombie'. I tried to imagine the English-language equivalent, perhaps DJ AG or Stick In The Wheel turning up outside court to play songs everyone knows, to crowds protesting an MC being hauled into court on drug charges (noting here the disproportionate ways that legislation relating to both terrorism and drug laws are policed and enforced).

The thing should be like the thing

My book Up the Youth Club came out in the autumn. In writing it, I had tried to do what I always do, which I can only describe as 'making the thing like the thing'. This often means trying to write about something in the spirit of whatever I'm writing about and sometimes means using the specific practices of ways of being that relate to the subject.