In the middle of Ukraine's fiercest winter of the war, many Ukrainians are unable to prepare hot meals or are unable to heat their homes while temperatures have dipped as low as -20C in the past few weeks. Harsher weather is forecast.

Russia has once again targeted Ukraine with sustained attacks on power stations, energy grids and heating nodes affecting electricity, as well as heating systems and water pumps.

Following the Russian strikes on January 20, around 5,600 apartment buildings in Kyiv were left without heating and almost half of Kyiv was believed to be without heat and power, affecting around one million people. The situation is so dire that the city has set up "heating tents" to help people stay warm in the freezing temperatures. Other cities have also been attacked.

Ukraine's president Volodymyr Zelensky declared the situation an energy emergency.

One factor is that as a legacy of Ukraine's membership of the Soviet Union, Russia probably holds deeper knowledge about Ukraine's centralised energy systems than an outside nation would generally have.

For decades Ukraine's energy system was linked to Russia and Belarus as part of a centralised grid, and was "tightly connected to Russia's energy architecture". While this did not mean Ukraine was dependent on Russia for its energy supply, it did mean that Russia played the central role in coordinating frequency and balancing supply and demand across the whole network.

Some Ukrainian officials have argued that the nature of these attacks suggests that Russian knowledge of Soviet-era energy systems has helped it to target Ukraine's energy centres.

There's another big factor for the Ukrainian authorities to struggle with.

While Ukraine's authorities were quick to restore heating in around 1,600 buildings, an estimated 4,000 remained without heating on January 21. The challenge in Ukraine is more severe than it might be in other countries because of the centralised systems for water, sewage and heating used by its urban neighbourhoods, known as district heating.

What is district heating?Ukraine still relies heavily on Soviet-era thermal heating systems using mostly gas. The percentage of households that rely on district heating varies by region and city, with a particularly high percentage of these buildings, mostly built in the 1960s, in densely populated urban cities including Kyiv.

Thermal power plants usually heat water which is then piped around districts and to individual pumping stations. It is then distributed to apartment buildings. But if the pipes are full of water and power for heating is off, the pipes can burst if the water freezes. Right now, with temperatures spiralling downwards this is a major threat.

Russian attacks on Ukraine leave thousands without heating in middle of winter.Each district heating system can serve tens of thousands of citizens across multiple buildings and, when powered with renewable energy, they can be significantly more efficient, cost-effective and low-carbon than individual boilers. District heating systems depend much more on fixed physical infrastructure, including large pipes and pumping stations, to circulate hot water.

But centralised infrastructure is inherently vulnerable to physical attack. Damage to a major transmission pipe or the loss of a key pumping station can disable heating across entire neighbourhoods, particularly during winter.

Russia has damaged around 8.5GW of Ukraine's power generation since October 2025, or around 15% of pre-war capacity. With the amount available nearly matching the amount generated there's little room to redistribute energy within the system.

Whatever the system's weaknesses may be, no energy system in the world is built to sustain continued bombardment.

Ukraine relies on nuclear powerUkraine's energy system is also largely dependent on nuclear power. Around half of Ukraine's electricity is nuclear-powered, with coal-fired power plants making 23% and gas-fired plants 9%. In all cases these are features of a highly centralised energy system.

Patterns of attacks indicate that Russian forces monitor where repairs are under way and then hit the same sites again once they are restored. This has compounded repair costs and prolonged the loss of critical services. Kyiv's mayor Vitali Klitschko said that the situation was difficult because most of those buildings that were being reconnected for the second time were damaged as part of a previous attack on January 9.

Russia uses "double-tap" strikes, where a second attack follows closely after the first. This often endangers emergency services and repair crews rushing to restore heat and electricity. Such tactics force officials to balance the urgent need to fix infrastructure with the risk to workers and civilians.

Even before the war, there were weaknesses in Ukraine's energy and power networks. Old water systems and heating devices — and often entire buildings — need to be reconstructed.

However, Ukraine had already started to reduce technical reliance on Russia before the war. The dependency on the post-Soviet system changed in March 2022, when Ukraine's grid was integrated with the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity, (Entso-E), a Europe-wide association of national electricity transmission system operators.

These attacks have had significant consequences on hospitals, transport systems, and vulnerable people in their homes. This devastating cycle of repeat strikes in the middle of an incredibly cold winter has intensified Russia's energy terror.

Pauline Sophie Heinrichs does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

How high will the sea eventually rise? Much depends on Greenland. muratart / shutterstock

How high will the sea eventually rise? Much depends on Greenland. muratart / shutterstockThis roundup of The Conversation's climate coverage was first published in our award-winning weekly climate action newsletter, Imagine.

"Observing Greenland from a helicopter," one scientist wrote last year, "the main problem is one of comprehending scale. I thought we were skimming low over the waves of a fjord, before … realising what I suspected were floating shards of ice were in fact icebergs the size of office blocks. I thought we were hovering high in the sky over a featureless icy plane below, before bumping down gently onto ice only a few metres below us."

This is the view described by Durham glaciologist Tom Chudley, when writing about his research showing the Greenland ice sheet isn't just melting - it's falling apart. Chudley and his colleagues found crevasses are growing fast, channelling meltwater deep into the ice sheet, accelerating its slide into the ocean.

And as the ice cracks, so does the geopolitical status quo.

Fingerprint ridges or office block crevasses?

JSCorbella / shutterstock

Fingerprint ridges or office block crevasses?

JSCorbella / shutterstock

Many world maps make Greenland seem even bigger than it actually is. The "Mercator projection" implies it's almost the size of Africa, when in reality it is "only" about as big as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Over my time in this job, I have noticed Greenland having a similarly outsized role in climate science. In recent years, The Conversation has published stories, among many others, on melting ice, climate-changing microbes, fast-adapting polar bears, Chudley's creaking crevasses, the race to map the world's most spectacular and remote fjords, and a skyscraper-sized tsunami that vibrated through the entire planet and no one saw. All relied on scientists - often in big international teams - having access to Greenland.

Read more: The Greenland ice sheet is falling apart - new study

Access denied?

But the political stability that allows these scientists to work there is also under threat. In a piece explaining why Greenland is indispensable to global climate science, Martin Siegert, a glaciologist who heads the University of Exeter's Cornwall campus, points out that Antarctica has been governed for decades by an international treaty that ensures it remains a place of peace and science. Greenland has no such protection.

"Its openness to research", writes Siegert, "therefore depends not on international law, but on Greenland's continued political stability and openness - all of which may be threatened by US control."

The stakes are high: if Greenland's colossal ice sheet fully melted, it would "raise sea level globally by about seven metres (the height of a two storey house)".

Read more: Why Greenland is indispensable to global climate science

An occupational hazard.

Jane Rix / shutterstock

An occupational hazard.

Jane Rix / shutterstock

Why the sudden urge to take over Greenland, anyway?

Many assume America's ambitions are ultimately about oil or other minerals. But Lukas Slothuus, who researches fossil fuel production at the University of Sussex, takes a more sceptical view on the supposed economic jackpot.

Logistical nightmaresGreenland does have vast natural resources, he says, but they won't necessarily translate into huge profits. That's because the logistics are so tough. Slothuus notes that: "Outside its capital Nuuk, there is almost no road infrastructure in Greenland and limited deep-water ports for large tankers and container ships."

He contrasts this with other potential mining operations around the world, which can "exploit public infrastructure such as roads, ports, power generation, housing and specialist workers to make their operations profitable". Greenland has none of this. That means "huge capital investment would be required to extract the first truckload of minerals and the first barrel of oil".

This is one reason why Siegert believes "economics dictates" Greenland's resources will "most likely be used to power the green transition rather than prolong the fossil fuel era". The sheer cost of extraction means the commercial focus is on "critical minerals": high-value materials used in renewable technologies from wind turbines to electric car batteries.

As Slothuus puts it, oil from Greenland is "implausible even in the event of a full US takeover".

"There are many reasons why the Trump administration might want to dominate the Arctic, not least to gain relative power over Russia and China. But natural resource extraction is unlikely to feature centrally."

Read more: Why Greenland's vast natural resources won't necessarily translate into huge profits

This hasn't stopped the superpowers, of course. And in the medium-term, Greenland looks set to host a massive military build up - whether or not the US takes over.

That's according to Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, a professor of war studies at Loughborough University. She says Greenland is in a strategic position that will only become more important as climate change opens up new shipping lanes, enabling further conflict in the far north. "The Arctic in general," she writes, "will become a showcase for the latest military technology the US has in its armouries."

I'm not aware of any research on the climate impact of a military showcase on or around a pristine ice sheet. But as our glaciologist in the helicopter warned us, the ice is already fragile enough.

To contact The Conversation's environment team, please email imagine@theconversation.com. We'd love to hear your feedback, ideas and suggestions and we read every email, thank you.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Over Christmas, vegetables, bananas and insulation foam washed up on beaches along England's south-east coast. They were from 16 containers spilled by the cargo ship Baltic Klipper in rough seas. In the new year, a further 24 containers fell from two vessels during Storm Goretti, with chips and onions among the goods appearing on the Sussex shoreline.

For most people this is a nuisance - or perhaps a bit of fun. For oceanographers like me, who study tides and currents, it is also an accidental experiment - a rare chance to watch the ocean move things around in real time. Think of it as a very large message in a bottle.

In reality, cargo has been falling off ships since traders first went to sea. What has changed is that, in the modern world, most goods are transported in standardised containers. Apart from oil, gas, vehicles, bulk grain, aggregates - and people - pretty much everything is moved this way.

More than 250 million containers are shipped around the world each year, and it is likely that over 80% of goods in your home travelled at some point in a container by sea.

Losses are rare. Industry group the World Shipping Council estimates that over the past ten years an average of 1,274 containers a year have been lost globally, out of hundreds of millions transported. This figure does vary: in 2020 a single huge ship the ONE Apus lost around 1,800 containers of its 14,000 load in a Pacific storm, while in 2024 global losses were estimated at just 576.

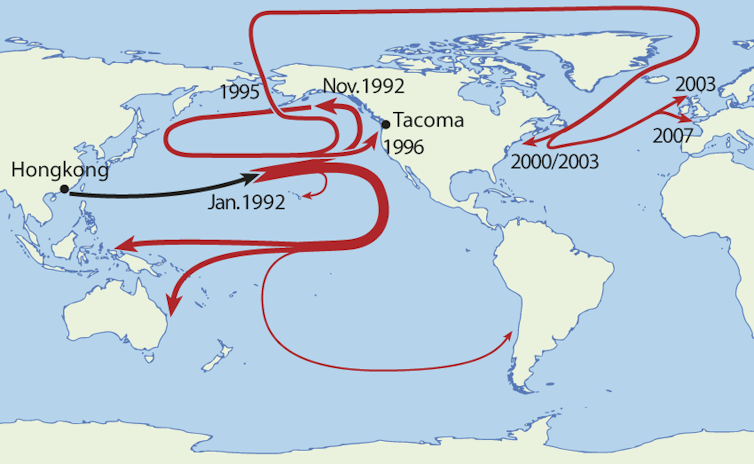

Ducks go globalSome losses make the news in unexpected ways. In January 1992, 12 containers washed off the Ever Laurel in the North Pacific. One of these contained 28,800 bath toys - plastic beavers, frogs, turtles and ducks - which spilled into the ocean and washed up on beaches around the Pacific over the next decade or more.

Curt Ebbesmeyer and James Ingraham, oceanographers from Seattle, tracked these so-called "friendly floatees" around the world and used them to improve scientific models of ocean circulation. In more recent years I've looked at the progress of these floatees into the Arctic and beyond.

How the friendly floatees made their way around the world.

NordNordWest / wiki, CC BY-SA

How the friendly floatees made their way around the world.

NordNordWest / wiki, CC BY-SA

Not all cargoes are this benign or useful. In January 2007, the MSC Napoli was hit by a major storm in the Channel and lost 114 containers, 80 of which washed up on beaches around Branscombe in Devon. Containers of wine, BMW motorbikes and perfumes drew locals to scour the beach for prizes but there were also far more sinister containers of explosives, weed killers, fertilisers and acid.

Both the cargoes and the containers themselves pose serious risks. Chemicals can destroy habitats, while containers can sometimes lurk one or two metres below the surface, kept semi-buoyant by trapped air, making them difficult to detect and capable of causing serious damage in a collision.

Designed for speed - not 100% securityModern container ships are designed for speed and efficiency in port. A single 400-metre vessel can carry up to 25,000 containers, many towering high above deck like a block of flats. The containers interlock and are secured using industry standard fixings - one reasons cranes are able to rapidly move them around a port. In severe storms, however, the forces involved can exceed what the fixings are designed to withstand, and containers can be dislodged, particularly those at the edge.

These ships are built to be loaded and unloaded very quickly.

MagioreStock / shutterstock

These ships are built to be loaded and unloaded very quickly.

MagioreStock / shutterstock

It is almost impossible to secure cargo 100% safely. To do so would mean smaller ships, with cargo held internally, reversing decades of efficiency gains. That would mean far more ships required to move the same volume of goods, higher costs for consumers, great fuel use per tonne of goods, and a higher overall risk of accidents. It would also clog up ports around the world.

The English Channel is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world and is regularly battered by storms. Southampton, the UK's second busiest container port, is also one of only a few worldwide that can accommodate the largest container ships. It is therefore no surprise that container losses are often visible along England's south coast.

Looking ahead, the risks are unlikely to diminish. Climate change is intensifying storms as oceans warm, while international trade continues to grow and ships become ever larger.

The ship owners - usually through their insurance companies - are responsible for cleaning up spills, but the system only works if the losses are reported. Until now, containers lost at sea have often gone unreported or their contents have been barely documented.

However, from January 1 2026, new international rules introduced by the World Shipping Council working with the International Maritime Organisation (the UN Agency responsible for shipping) will require ship owners to report all cargo losses and their contents. While this may not prevent containers being lose at sea, it should improve tracking, recovery and accountability.

If you see a container on a beach, resist the temptation to see it as an early Christmas present. You should report it immediately to the coastguard - scavenging wrecks can count as theft. In the UK, who owns what washes up is decided by a single civil servant with the grand title of the Receiver of Wreck. Critically, that container may contain a far less pleasant cargo that could ruin your Christmases for years to come.

Simon Boxall does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Pak Mun Dam in Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand. Sabrina Kathleen/Shutterstock

Pak Mun Dam in Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand. Sabrina Kathleen/ShutterstockThirty years after the Pak Mun dam was built in Thailand, the traditional way of fishing in the Khong Chiam district has completely stopped as the dam blocks the seasonal migrations of a wide range of fish.

Many men have had to leave their homes to find work elsewhere because they couldn't fish or farm locally anymore, while their wives are often left alone to look after their children. People with disabilities and the elderly have not been included in compensation and livelihood rehabilitation programmes, even though they are among the groups most affected by changes in mobility, access to water and food systems.

My team and I have been documenting the knock-on effects of this dam development by carrying out interviews with people living in these communities. My research highlights that if the environmental consequences of dam building had been better predicted and monitored, a lot of the ongoing disruption could have been avoided.

In 1982, a environmental impact assessment for the Pak Mun dam was prepared by a team of Thai engineering consultants. Environmental impact assessments are used to identify, predict and evaluate the possible consequences of a proposed project before it begins. They have been in use for many years, but some governments bypass their recommendations.

If completed more rigorously, this assessment for the Pak Mun dam could have anticipated these negative social and environmental consequences and might have influenced decisions about the building and maintenance of this dam. But according to research, this impact assessment was weak.

One study noted that the environmental impacts of the dam - mainly on fish - were either unquantified or understated. Another study noted that the site location had moved and that required a new assessment rather than replying one the first one. The limits of this assessment has led to ongoing contestation between the central and provincial government and the affected communities and activists.

This is far from the only example of a lack of consideration for the long-term knock-on effects of dams on communities and nature. In 2025, the Indian government allegedly fast-tracked the construction of the enormous Sawalkot hydropower project on the Chenab river without conducting any environmental and social impact assessment.

Large-scale projects like this affect millions of people and the environment around them. Without ample impact assessments, they proceed without establishing just what effect they will have on the surrounding landscape, nature and communities. As a result, any negative consequences are not easily avoided.

While this new political dynamic of circumventing impact assessments is worrying, social and environmental impact assessments are valuable if used appropriately. As part of my research, I have spoken to dozens of impact assessment consultants and academics to assess the status quo.

By 2033, the global market for environmental impact assessments could be worth an estimated US$5.8 billion (£4.3 billion). While the impact assessment process is seen as valuable by consultants and academics, some of our interviewees worried that costly recommendations often get lost in the process of project implementation once the document has been produced.

Ideally, impact assessments should be based on scientific knowledge and involve substantial public participation and situated community knowledge, especially by those who are at risk of adverse consequences, as well as clear accountability mechanisms.

In practice, there are problems. Impact assessment is a political process; it is not based purely on evidence and scientific facts. It is influenced by the economics of dam building. Dams are often also important symbols of nationalism, so they hold high political status.

Without ensuring systematic follow-up to an impact assessment, it can simply become a paper chase to secure a development permit. With more consideration, the "afterlife" of impact assessments can be much more effective.

Who is responsible?Who, in terms of responsibility, should be held accountable for shortcomings in the implementation of impact assessment plans? Should it be the government that should be responsible for making sure the different regulations and norms are followed?

Should it be the commercial banks, development banks and bilateral donors (such as foreign aid provided by the UK government's Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office) that fund projects who should monitor the requirements they had elaborated? Or should it be the private sector?

My research shows that the responsibilities lie with all of these parties.

In most countries, most of the information and data is controlled by the proponents of building the dam. Project managers and engineers may be suspicious of external impact assessor consultants, so they do not always share the relevant information.

Civil society, ranging from local campaign groups and activist to non-governmental organisations, have pushed for standards and laws that ensure rules are followed during and after any impact assessment. For this to work, impact assessments need to be dynamic so responses to possible changing consequences can change.

When environmental policy and tools like impact assessments are being questioned, it is even more important to create a policy process that ensures long-term accountability for impact assessments and prevent further losses and damages to the communities and the environment.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Jeremy Allouche receives funding from the British Academy, for the project, Anticipatory evidence and large dam impact assessment in transboundary policy settings: Political ecologies of the future in the Mekong Basin. The author would like to thank the other team members, Professor Middleton (Chulalongkorn University Thailand), Professor Kanokwan Manorom (Ubon Ratchathani University, Thailand), Ass. Professor Chantavong (National University of Laos) & Dr. Kanhalikham (National University of Laos) for their input

Listening to the sounds of birdsong may help to reduce stress. BalanceFormCreative/ Shutterstock

Listening to the sounds of birdsong may help to reduce stress. BalanceFormCreative/ ShutterstockThere's no question that being in nature is good for wellbeing. Research shows that experiencing nature and listening to natural sounds can relax us.

A key reason for these benefits may be because of the appeal of birds and their pleasant songs that we hear when in nature.

Studies show that people feel better in bird-rich environments. Even life satisfaction may be related to the richness of the bird species in an area.

My colleagues and I wanted to better study the relationship between wellbeing and birdsong. We conducted an experiment in which 233 people walked through a park - specifically the University of Tübingen's botanical garden. The walk took about half an hour.

Participants filled out questionnaires on their psychological wellbeing both before and after their walk. We also measured blood pressure, heart rate and cortisol levels (in their saliva) to get a better understanding of the physiological effects the walk had on wellbeing. Cortisol is considered an important stress hormone that can change within just a few minutes.

In order to get a good understanding of the effect birdsong had on wellbeing, we also hung loudspeakers in the trees that played the songs of rare species of birds - such as the golden oriole, tree pipit, garden warbler or mistle thrush.

To decide which additional bird songs should be played by the loudspeakers, we looked at the results of a previous study we had conducted. In that study, volunteers listened to more than 100 different bird songs and rated them based on how pleasant they found them to be.

We used the bird songs that had been most liked by participants in that experiment. However, to avoid annoying the birds living in the garden, we only chose bird songs that did not disturb the environment. We also mapped all resident species in the area and avoided broadcasting their songs.

Participants were randomly split into five distinct groups. The first and second groups went for a walk through the garden with birdsong being played on loudspeakers. The second group was also instructed to pay attention to birdsong.

The third and fourth groups also walked through the garden, but this time they only heard natural birdsong - we did not have additional speakers playing birdsong in the area. The fourth group was also instructed to pay attention to the natural birdsong.

Those who focused on birdsong reported better mental wellbeing.

edchechine/ Shutterstock

Those who focused on birdsong reported better mental wellbeing.

edchechine/ Shutterstock

The fifth group was the control group. These participants went for a walk through the garden while wearing noise-cancelling headphones.

Benefits of birdsongIn all groups (even the control group), blood pressure and heart rate dropped - indicating that physiological stress was reduced after the walk. Cortisol levels also fell by an average of nearly 33%.

Self-reported mental wellbeing, as measured by the questionnaires, was also higher after the walks.

The groups who focused their attention on the birdsong saw even greater increases in wellbeing. So while a walk in nature had clear, physiological benefits for reducing stress, paying attention to birdsong further boosted these benefits.

However, the groups who went for a walk with the loudspeakers playing birdsong did not see any greater mental and physiological wellbeing improvements compared to the other groups.

This was a surprise, given previous studies have shown birdsong enriches wellbeing. Bird species diversity has also been shown to further improve restoration and relaxation.

One possible explanation for this finding may be that participants recognised the playback sounds as being fake - whether consciously or unconsciously. Another explanation could be that there might be a threshold - and having a higher number of bird species singing in an area does not improve wellbeing any further.

Appreciating birdsongOur results show that a walk in nature is beneficial in and of itself - but the sounds of natural birdsong can further boost these wellbeing benefits, especially if you make a concerted effort to pay attention it.

You don't even need to know a lot about birds to get these benefits, as our study showed. The positive effect was seen in everyone from casual birdwatchers through to bird nerds.

Our study's results are a good message for everyday life. You don't need a visit to bird-rich environments to make you happy. It seems more important to focus on the birds that are already there, listen to them and enjoy them.

The results also have implications for park design, showing that the sound of birdsong in general - rather than the number of species living there or how rare they are - is of key importance when it comes to wellbeing.

So even just a half hour walk outside while taking the time to notice birdsong could reduce your stress and improve wellbeing.

Christoph Randler does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

4045/Shutterstock

4045/ShutterstockPlastic pollution is one of those problems everyone can see, yet few know how to tackle it effectively. I grew up walking the beaches around Tramore in County Waterford, Ireland, where plastic debris has always been part of the coastline, including bottles, fragments of fishing gear and food packaging.

According to the UN, every year 19-23 million tonnes of plastic lands up in lakes, rivers and seas, and it has a huge impact on ecosystems, creating pollution and damaging animal habitats.

Community groups do tremendous work cleaning these beaches, but they're essentially walking blind, guessing where plastic accumulates, missing hot spots, repeating the same stretches while problem areas may go untouched.

Years later, working in marine robotics at the University of Limerick, I began developing tools to support marine clean-up and help communities find plastic pollution along our coastline.

The question seemed straightforward: could we use drones to show people exactly where the plastic is? And could we turn finding the plastic littered on beaches and cleaning it up into something people enjoy - in other words, "gamify" it? Could we also build on other ways that drones have been used previously such as tracking wildfires or identifying shipwrecks.

Building the technologyAt the University of Limerick's Centre for Robotics and Intelligent Systems, my team combined drone-based aerial surveillance work with machine-learning algorithms (a type of artificial intelligence) to map where plastic was being littered, and this paired with a free mobile app that provides volunteers with precise GPS coordinates for targeted clean-up.

The technical challenge was more complex than it appeared. Training computer vision models to detect a bottle cap from 30 metres altitude, while distinguishing it from similar objects like seaweed, driftwood, shells and weathered rocks, required extensive field testing and checks of the accuracy of the detection system.

The development hasn't been straightforward. Early versions of the algorithm struggled with shadows and confused driftwood for plastic bottles. We spent months refining the system through trial and error on beaches around Clare and Galway so the system can now spot plastic as small as 1cm.

We conducted hundreds of test flights across Irish coastlines under varying environmental conditions, different lighting, tidal states, weather patterns, building a robust training dataset.

How a drone finds plastic litter. Ireland's plastic problemThe urgency of this work becomes clear when you look at the Marine Institute's work. Ireland's 3,172 kilometres of coastline, the longest per capita in Europe, faces a deepening crisis.

A 2018 study found that 73% of deep-sea fish in Irish waters had ingested plastic particles. More than 250 species, including seabirds, fish, marine turtles and mammals have all been reported to ingest large items of plastics.

The costs go beyond harming wildlife, and the economic impact can be significant.

Our drone surveys revealed that some stretches of coast accumulate plastic at rates five to ten times higher than neighbouring areas, driven by ocean currents and river mouths. Without systematic monitoring, these hotspots go unaddressed.

Making the technology accessibleThe plastic detection platform accepts drone imagery from any source, such as ordinary people flying their own drones.

Processing requires only standard laptop software. Users upload footage and receive GPS coordinates showing detected plastic locations. The mobile app, available free on iOS and Android, displays these locations as an interactive map.

Plastic is regularly found on beaches around Europe.

Author's own.

Plastic is regularly found on beaches around Europe.

Author's own.

Community groups, schools and individuals can see nearby plastic pollution and find it, saving a lot of time.

It has already been tested with five community groups around Ireland with positive results, averaging 30 plastics spotted per ten-minute drone flight, varying by location.

Working through the EU-funded BluePoint project, which is tackling plastic pollution of coastlines around Europe, we've distributed over 30 drones to partners across Ireland and Europe, including county councils and environmental organisations.

The technology has been deployed in areas including Spanish Point in County Clare, where the local Tidy Towns group (litter-picking volunteers), were named joint Clean Coast Community Group of the Year 2024.

Organising a litter pick. Video by Propeller BIC (Waterford). The wider waste storyThis is part of a broader European effort to address plastic pollution. Partners such as the sports store Decathlon are exploring how to transform recovered beach plastics into new consumer products - sports equipment, textiles and components.

The challenge isn't just collection. Beach plastics arrive contaminated with sand and salt, in mixed types and grades. Our ongoing research characterises what's actually found on Irish coastlines, providing manufacturers with data to design appropriate sorting and recycling processes.

The open source software platforms and the drone technology have already been used in nine countries, engaging more than 2,000 people. Pilot programmes are running in France, Spain, Portugal, Brazil and the UK. What began as a question about making beach clean-ups more effective has evolved into a practical system connecting citizen action to environmental outcomes.

Community feedback from pilots has been overwhelmingly positive. Groups report that the drone-derived GPS coordinates transform clean-up work. One participating Tidy Towns group said that volunteers now head straight to flagged locations.

Groups have also reported increased participation, the gamification aspect appeals to families and participants who might not volunteer otherwise. Additionally, the data we've gathered so far is being used by local authorities to understand litter patterns and inform policy decisions around waste management and coastal protection.

Gerard Dooly works for the University of Limerick, Ireland. He receives funding under the BLUEPOINT project (EAPA_0035/2022), co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Atlantic Area Programme.

The Trump administration recently announced it would pull out of around 150 international and global organisations, including two foundational pillars of global climate organisations: the political United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the scientific Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In terms of media coverage this was a one-day wonder, understandably overshadowed by mass government killings in Iran and the actions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) in Minneapolis.

But the acronym Ice brings to mind a different history. Thirty five years ago another "Ice" - the Information Council for the Environment - was created to spread confusion and hostility. As the late Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Ross Gelbspan revealed, this Ice was funded by coal companies as part of a targeted effort to cultivate doubt around the "greenhouse effect" among low information voters, especially older white men without college educations.

Ice was eventually exposed and melted away. But the broader effort continued, spearheaded by the Global Climate Coalition, formed by oil companies and carmakers. Their goal was rational: to protect their profits by softening US carbon reduction commitments, such as those agreed at the 1997 Kyoto conference.

Bad for the public, bad for capitalFor decades, US engagement with climate change was characterised by delay. This "made sense" for certain interests. When George H.W. Bush weakened the UNFCCC or his son pulled out of the Kyoto protocol, they were operating on a certain economic logic: protect American industry from regulation.

Trump is very different.

Over the past 20 years "clean tech" has gone mainstream and is now seen as a way for corporations to secure market share. This was matched by policymakers, and the Biden administration's Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) threw enormous sums - grants, loans, tax-breaks - at "green" reindustrialisation.

Big companies were making loads of money. The true capitalist move would surely be to keep profits flowing. Yet Trump is rolling back the IRA.

This is not in the interests of the public, but it's not generally in the interests of capital either. At best, Trump's moves favour a dying form of capitalism over the emerging one.

Insurers facing uninsurable risks, carmakers who had committed to electric vehicles, and the clean tech sector all lobbied to keep the IRA. They would be making more money had the green industrial policy continued. Even major oil companies seem lukewarm towards a policy of total isolationism.

Things were better beforeSo, if it isn't about money, what's going on?

Trump and his allies share a worldview shaped by conservative backlash against civil rights, feminism, environmentalism and even scientific authority itself. The nostalgia they invoke is for a partly-imagined 1950s, a time when white technocratic men were in charge, schools were segregated, women were in the kitchen, and polluting industries could do as they pleased.

In my own academic research, I found something similar played out in Australia. For many older white men used to industrial dominance, the transition to renewables represents a psychological loss of control similar to the social upheavals of the 1960s. Their war on climate policy is less about economics and more about reasserting a "natural order" where traditional hierarchies remain unchallenged.

Whether in Australia or the US, being too young to have lived through these changes provides no immunity to the myth that everything was better before they were born. For a long time, however, this reactionary impulse was kept in check by political realities.

In the 1980s, Reagan appointees learned that pitched battles with environmental interests can be costly. They learned to use the language of technology, and to cast doubt rather than issue outright denials. Crucially, they learned the value of under-funding institutions to the point of incapacity, rather than abolishing them entirely, so that environmentalists had no easy-to-explain causes to rally behind.

Trump's administration is unwilling to pretend. Alongside the UNFCCC and IPCC pullout, it has been attempting to dismantle the state's ability to measure reality through key scientific institutions such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the Environmental Protection Agency. Trump and those around him are not doing this because it saves money, but because the science itself offends their worldview. It is a refusal to admit the political enemies they have derided for decades might actually have been right.

We are used to thinking of politicians and bureaucracies as captives of vested interests with predictable economic motives. But Trump's climate policy suggests something different is also at work. It recalls the moment when former UK prime minister Boris Johnson is reported to have dismissed corporate concerns about Brexit with a blunt "fuck business".

Trump's climate policy is the geopolitical equivalent. It is a scorched earth strategy that sacrifices the climate to win a culture war. And the terrifying reality is they seem willing to do this just to avoid admitting they were wrong.

Marc Hudson was previously employed as a post-doctoral researcher on two separate Industrial Decarbonisation Research & Innovation Centre projects.

PradeepGaurs/Shutterstock.com

PradeepGaurs/Shutterstock.comThe scientist Stephen Hawking lived with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the most common type of motor neurone disease, for 55 years. He was one of the longest-surviving people with the condition.

However, most people with motor neurone disease are not as lucky. It often progresses quickly, and many pass away within two to five years of diagnosis. There is still no cure. Genetics account for only about 10% of cases, and the rest of the causes are still largely a mystery.

A new study in the journal Jama Neurology showed one possible contributor: air pollution, both for the risk of developing motor neurone disease and for how it progresses.

In the study, my colleagues and I examined air pollution levels at each of the 10,000 participant's home address for up to ten years before diagnosis. We focused on two common types of outdoor pollutants that are widely linked to health harms: nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter.

Particulate matter is made up of tiny airborne particles (far thinner than a human hair). It is usually grouped by size: PM2.5 (less than or equal to 2.5 micrometres), PM10 (less than or equal to 10 micrometres), and the in-between fraction PM2.5-10 (between 2.5 and 10 micrometres).

We found that being exposed to air pollution over the long term, even at the fairly low levels typically seen in Sweden, was linked to a 20-30% higher chance of developing motor neurone disease. What's more, the pattern still held up when we compared siblings, which helps rule out a lot of shared factors like genetics and growing up in the same environment.

We also observed that people with motor neurone disease who had been exposed for years to higher levels of PM10 and nitrogen dioxide faced a greater risk of death or of needing a machine to help them breathe.

These pollutants are typically produced by nearby road traffic. Taken together, the results suggest that pollution generated close to home, especially from local vehicle emissions, may have a stronger effect than particulate matter carried in from farther away, which tends to account for much of the broader day-to-day variation in particulate matter levels.

Stephen Hawking survived for 55 years with ALS.

Koca Vehbi/Shutterstock.com

Stephen Hawking survived for 55 years with ALS.

Koca Vehbi/Shutterstock.com

Doctors regularly keep tabs on how well patients are managing everyday functions across a few key areas. These include bulbar function (speech, saliva control and swallowing), fine motor function (handwriting, cutting food, dressing and personal hygiene), gross motor function (turning in bed and adjusting bedding, walking and climbing stairs) and breathing (shortness of breath, difficulty breathing when lying flat, and signs of respiratory failure).

The participants in our study were assessed about every six months after diagnosis. We then looked at how quickly the disease was getting worse overall and within each of these domains. Patients whose decline was faster than that of 75% of other patients were labelled as having faster progression.

We found that long-term exposure to air pollution was associated with higher odds of having faster progression overall, particularly affecting motor and respiratory function, but not bulbar function.

Broader implicationsThe reasons for these differences are not yet clear. One possibility is that different parts of the nervous system vary in their vulnerability to pollution-related injury. It could also be because air pollution has consistently been linked to chronic lung diseases, reduced lung function and infections, all of which have been associated with poorer outcomes in ALS.

We accounted for many factors that could influence both air pollution exposure and motor neurone disease risk, including personal and neighbourhood income, education, occupation and whether participants lived in urban or rural areas. Our study did not have data on smoking habits or indoor air pollution exposure. However, there is no evidence suggesting that people with and without motor neurone disease differ significantly in these factors in ways that would explain our findings.

These results bring us closer to understanding motor neurone disease and may eventually help with earlier diagnosis and better treatment. But there's a wider message here. We're all exposed to air pollution, and the evidence keeps mounting that it harms our health in serious ways. Cleaning up our air could do far more good than we realise.

Jing Wu receives funding from Karolinska Institutet's Research Foundation.

The red-nosed cuxiu is endangered. Cavan-Images/Shutterstock

The red-nosed cuxiu is endangered. Cavan-Images/ShutterstockLook down at the rainforest floor. Rotting flowers shift under the assault of tiny petal-eating beetles. Vividly coloured fungi pop up everywhere like the strange sculptures of a madly productive ceramicist.

Look in front of you and heliconias and calatheas, tropical plants familiar from garden centres and greenhouses, vie for the attention of hummingbirds with scarlet and orange flowers.

Look up and the distant canopy offers a full spectrum of shades of green, along with clusters of flowers and fruits in a bewildering range of shades, shapes and sizes.

You'd be excused from thinking that life in a tropical forest is easy. A lazy arm movement being all that's needed to secure the next mouthful of food. But it's not like that at all.

Life in the rainforest demands extraordinary adaptations.

Which is why I found myself stepping out of a small canoe on the Tapajós River in Brazil's central Amazon to collect the remnants of the most recent meal of the endangered red-nosed cuxiu monkey (Chiropotes albinasus) for my recent study.

They are like no other monkey on Earth. Many species have ecological parallels on other continents, often with very similar physical and behavioural adaptations. For example, spider monkeys and gibbons, chimpanzees and capuchin monkeys. But cuxius, and their close relatives the uacaris and sakis, are a uniquely South American phenomenon.

Cuxius are cat-sized animals, with canines bigger than human teeth, even though their skull is the size of an orange. Although other primates have massive canines too (think baboons, mandrills or chimps) these are for display. Those of the cuxiu are the real deal; designed for cracking open hard, unripe fruits to get at the equally unripe and hard seeds. They eat a range of fruits that include relatives of the Brazil nut, acacia tree and oleander.

Humans would need a hammer to crack open this kind of fruit. But cuxius and their near relations bite them open. Powered by massive muscles, the jaws can deliver a bite which, if scaled for size, is equal to that of a jaguar. They eat hundreds of rock-hard fruits a week, tens of thousands over their ten-year life span.

So, I wanted to know: how do they avoid cracking their teeth along with the nuts? We know their skulls are evolved to disperse the shock of a bite. But scientists have long been mystified by how the cuxiu avoids breaking its teeth through the sheer repetitive strain.

My findings revealed that cuxius are a lot smarter and more subtle than anyone thought.

Pick up a walnut and you'll notice a thin line running around the hard shell. This is the suture, and it's where the shell would naturally break open to free the seed when it ripens. It's also a lot less resistant to puncture than the rest of the fruit. Fruits with sutures dominate the diet of the red-nosed cuxiu, so I wondered if this could be the key to the cuxiu's success.

Measurements of the force needed for a copy of a cuxiu canine to penetrate fruit outer husks showed this was the case. It took up to 70% less force to go in at the suture than elsewhere on the fruits the cuxiu ate.

The red-faced spider monkey is an ateline monkey, with a highly athletic lifestyle.

Diego Grandi/Shutterstock

The red-faced spider monkey is an ateline monkey, with a highly athletic lifestyle.

Diego Grandi/Shutterstock

My examination of skulls held in London's Natural History Museum showed canine breakages were no more common in cuxius than in capuchins (which use either their molars or stone tools to break hard fruits) or ateline monkeys (which eat either soft pulpy fruits or leaves). Avoiding dental damage is smart - with no dentists in the forest a split tooth is a quick path to a slow death by starvation. And it allows the cuxius and their relatives to access unripe seeds, a food source few other animals can exploit.

This mirrors tactics used by carnivores like big cats, who bite prey at vulnerable spots to avoid breaking their teeth.

Then there's the fact that every animal in the rainforest needs to be its own doctor, physiotherapist and fitness coach. With no first aid stations for bitten, twisted or shocked bodies, it's best to avoid things going wrong in the first place. This is also true for actions that, through sheer repetition, could cause breakage through stress.

Survival in the rainforest depends on vigilance, cunning survival strategies and Olympian levels of fitness. An animal's survival depends not only on knowing what to eat but how to eat it. Seconds count when a bite too many can mean missing the one key glance skywards that stops you becoming someone else's breakfast.

Living in the top of the canopy of either rainforest or flooded forest, moving huge distances and doing so very fast, makes cuxius a challenge to observe. I first became interested in cuxius and uacaris because they are hard to study and, as a result, were so little known. But, soon after I started working with them, I realised cuxius and uacaris are like extreme sports athletes, pushing the boundary of what is possible in a monkey.

And they aren't the only ones.

Swinging and hanging between the trees, the life of a spider monkey is like a perpetual parallel bar performance, not for a few brief minutes, after months of rigourous training as in humans, but all day, every day. No gold medal and long retirement, just surviving till dusk and starting again at dawn.

Additionally, while not exactly Olympian, the energy howler monkeys use during their daily calling bouts is similar to that of a mid-aria opera singer. Except that the monkeys must perform twice a day for a lifetime.

Sadly, animals' Olympian abilities are no match for humans, whose use of tools is the equivalent of competitors using steroids or robotic enhancements. And, since it is clear that humans are not as smart as we are skilled, rainforest loss continues at a pace that even evolution - formerly the world's best trainer - cannot have prepared them for.

Adrian Barnett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Creating new value on old plantation land in Kerala, India. Sudheesh R.C., CC BY-NC-ND

Creating new value on old plantation land in Kerala, India. Sudheesh R.C., CC BY-NC-NDIn the early hours of July 30 2024, a landslide in the Wayanad district of Kerala state, India, killed 400 people. The Punjirimattom, Mundakkai, Vellarimala and Chooralmala villages in the Western Ghats mountain range turned into a dystopian rubble of uprooted trees and debris.

A coalition of scientists that quantifies the links between climate change and extreme weather, known as World Weather Attribution, highlighted that human-induced climate change caused 10% more rainfall than usual in this area, contributing to the landslide.

Known for its welfare achievements such as universal literacy, public health and education, Kerala's disaster management involved a swift relief response and the announcement of rehabilitation measures. But our research into the consequences of long-term environmental change reveals the crevices in this state-citizen relationship.

The Kerala government's response to the landslide has focused on two townships - one in Kalpetta and the other in Nedumbala - that are promised to be of high-quality construction, with facilities characteristic of upmarket, private housing projects. Of the total 430 beneficiary families, each will be given a 93m² concrete house in a seven-cent plot (a cent is a hundredth of an acre). There will be marketplaces, playgrounds and community centres at both sites.

An AI-generated video of the Kalpetta township promised a glittering new life for its residents. Construction of the two sites was entrusted to the Uralungal Labour Contract Cooperative Society, a labour union known for building quality infrastructure, to raise credibility.

A building damaged by the 2024 landslide in Wayanad.

Wikimedia Commons/Vis M, CC BY-NC-ND

A building damaged by the 2024 landslide in Wayanad.

Wikimedia Commons/Vis M, CC BY-NC-ND

A man we spoke to as part of our ongoing research in Vellarimala was happy about the money he will make from rising property prices once his household receives a new home. "It is a great deal," he told us. "We get seven cents of land and a new house. We estimate the property [will] hit a value of 10 million rupees (£85,600) in a few years. Also, since the government provided the house, we just have to protest if there is a complaint."

We also spoke to two citizen groups that mobilised victims after the landslide, enabling settlers - who came to the area as plantation labourers during colonial rule in the 20th century - to voice their grief, loss and trauma. This highlighted their history of migration from the plains of Kerala. Although they sought optional cash compensation initially, they have largely accepted being given a new home in the township, drawn by its future value.

But while township development seems to be an apt response, Kerala will struggle to cope with recurring cycles of disasters and disaster management without addressing the factors that trigger or amplify these calamities.

The townships are being built on 115 hectares of two tea plantations that have been bought by the Kerala government. With roots in British colonial rule, plantations represent a significant alteration of Wayanad's ecology. The landslide's route was full of tea plantations and most affected families were non-Indigenous plantation workers.

Tourism is also booming here, with hundreds of resorts, homestays and hotels, and a glass bridge that welcomes tourists to visit the forests and plantations of Vellarimala.

Less than three miles away, a landslide in 2019 in Puthumala killed 17 people. Although it was a warning, construction of buildings has continued unchecked. A tunnel that connects Wayanad with the plains of Kerala has been proposed, despite a state government committee report highlighting it would pass through areas that are at a moderate-to-high risk of landslides.

Differing valuesResettlement plans that focus on glitzy townships can fail to consider the most marginalised people, especially in societies like India that are marked by social hierarchies. A couple of Indigenous families, referred to as Adivasis in India, were initially offered space in the township. They refused it, citing their separation from the means of livelihood and cultural resources that the nearby forests provide.

For a long time, they have resisted efforts to relocate them from the forests - first in the name of animal conservation, and now because of the threat of climate disasters. This is despite the efforts of the government's forest department to portray the shifting of these families as a heroic rescue effort.

A 'model' house on display at the township under construction.

Sudheesh R.C., CC BY-NC-ND

A 'model' house on display at the township under construction.

Sudheesh R.C., CC BY-NC-ND

Two versions of the value attached to land are clashing here. Settlers see land as a commodity, so prize the two townships announced in Wayanad for their increasing land value. But Indigenous families hold deep cultural ties with the lands they are being asked to leave behind.

This is not just a romanticised connection with nature. Indigenous families will have to forgo hard-won forest rights. Leaving means losing access to honey, resins and medicinal plants that they trade for cash when food from the forests is insufficient.

Disasters like the Wayanad landslide expose the faultlines in both crisis management and state-citizen relationships. How a disaster is handled shows the state believes people can be easily moved from one site to another, while extraction and capitalist accumulation must continue.

Disasters also reveal whose loss is valued by the state and whose is not. While settlers' losses were compensated through townships that hold the possibility of rising property value, Indigenous citizens' loss of deeper ties with the land and forests remains unaddressed.

We believe this calls for an urgent rethink. Disaster responses demand more than relocation of people from one vulnerable site to another, perpetuating an endless series of calamities and reconstruction. It demands a fundamental change in the model of development.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Ipshita Basu receives funding from the British Academy Knowledge Frontiers: International Interdisciplinary grant for the project Planetary Health and Relational Wellbeing: Investigating Ecological and Health Dimensions of Adivasi Lifeworlds. Mary K. Lydia, Reshma K.R., Anusha Joshy and Manikandan C. have provided inputs for the research.

Sudheesh R.C. receives funding from the British Academy Knowledge Frontiers: International Interdisciplinary grant for the project Planetary Health and Relational Wellbeing: Investigating Ecological and Health Dimensions of Adivasi Lifeworlds.

Canetti/Shutterstock

Canetti/ShutterstockCities across the UK are investing in new cycle lanes and traffic restrictions to cut congestion, improve air quality and promote active travel for better health. Yet, if recent debates are anything to go by, you might think such measures were deeply unpopular.

The introduction of protected cycle lanes and low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) often sparks vocal opposition from local groups, who call for schemes to be delayed or scrapped.

For instance, in London, Kensington and Chelsea council removed cycle lanes from Kensington High Street after a short-term trial in 2020. Meanwhile, in Oxford, there have been calls to reopen residential streets to again allow through traffic during emergencies. Concerns often focus on cycle lanes taking up valuable road space and on LTNs displacing motor traffic onto surrounding boundary roads.

These discussions may give the impression that the public is firmly against cycling initiatives and traffic restrictions. However, our research suggests that strong support for them can be found, but how schemes are designed and introduced is crucial.

Our recent study, which analysed more than 36,000 UK-based tweets about cycle lanes and LTNs between 2018 and 2022, found that most social media posts were positive. There were 10,465 negative, 14,370 positive, and 12,142 neutral tweets.

Sentiment about the measures did shift over time, with a spike in negative reactions in the summer of 2020 when the government announced the emergency active travel fund, a scheme that provided rapid funding to local authorities to deliver walking and cycling infrastructure to support social distancing during the COVID pandemic. However, overall, positive tweets outnumbered negative ones.

The analysis also showed that criticism focused less on the principle of cycling itself and more on the design and implementation of measures. Complaints about poor quality cycle lanes or lack of consultation were far more common than outright rejection of active travel, and were made by both cyclists and drivers.

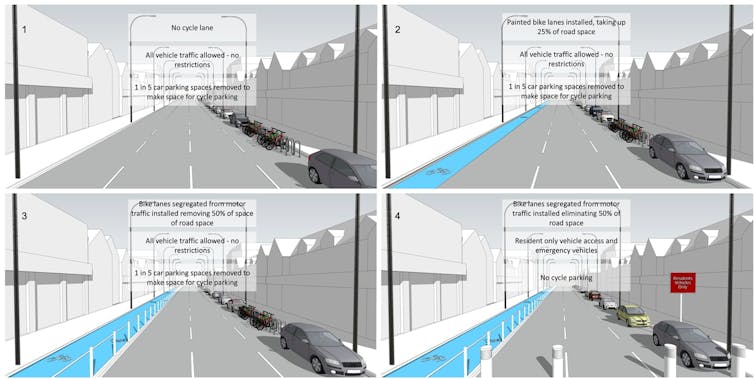

Our other recent research tells a similar story. We showed more than 500 people images of different street layouts and asked them to choose their most and least preferred elements. The designs varied in how they combined cycle lanes, traffic restrictions, and parking, with different amounts of space reallocated from roads or pavements.

The results were clear. Segregated cycle lanes - those physically separated from cars - were popular with both regular cyclists and regular drivers. Painted lanes on the road were far less liked, while the option of having no cycle lanes at all was the least popular with both groups.

Four of the 27 images shown to people in the study.

Author's image

Four of the 27 images shown to people in the study.

Author's image

Where the space came from also mattered. People strongly preferred schemes that took cycling space from the road rather than from pathways. But there was one consistent red line: parking. Even participants who identified as regular cyclists were reluctant to support layouts that involved removing car-parking spaces.

This suggests that resistance is less about cycling infrastructure itself and more about specific design trade-offs. Taking a modest amount of road space is widely accepted but removing parking risks triggering backlash.

Why do some people oppose cycle lanes and traffic restrictions so strongly? Part of the answer lies in identity. Our study found that those who strongly identified as "drivers" were more hesitant about giving up road space to cyclists, while self-identified "cyclists" were more supportive.

But the biggest divide was not between cyclists and drivers. Both groups often preferred the same measures. The strongest opposition came instead from a small group who see new cycling infrastructure as an infringement on their "freedom" to travel the way they want. This group consistently preferred the status quo over all options that would reallocate space to cyclists or restrict vehicle access.

This way of thinking may be rooted in what researchers call motonormativity, a deep-seated assumption that roads exist primarily for cars and that drivers' needs should come first. Within this context, giving space to cyclists is seen as taking something away from motorists, not expanding people's freedom to travel as they choose.

Our social media study sheds further light on the themes that shape public debate. Positive posts often focused on community benefits and safer streets. Negative conversations, by contrast, were dominated by concerns about how schemes were put in place. Tweets frequently criticised councils for poor consultation, accused politicians of ignoring local voices, or pointed to schemes being rolled out in confusing or inconsistent ways.

This matters because it shows that frustration is often directed less at cycle lanes or traffic restrictions themselves than at how they are introduced. In other words, there may be opposition not because people reject the idea of safer streets, but because they feel decisions are imposed on them or poorly managed. This underlines the importance of early and meaningful engagement if new infrastructure is to win lasting support.

So what are the key lessons of this research? First, visible opposition is not the whole story. Protests and headlines may give the impression that cycle lanes are deeply unpopular, but most people - including both drivers and cyclists - support new infrastructure and even traffic restrictions, as long as they are well designed and involve only modest changes. Parking is a sensitive point, but overall support for change is broader than the noise suggests.

Second, the strongest opposition comes from those who see new cycle lanes and restrictions as an attack on their freedom to drive. This group is relatively small but may be among the most vocal. Their concerns need to be acknowledged, but also reframed in light of the reality that limited road space must serve everyone: drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians alike.

Finally, it is not just about what gets built, but also how it is introduced. Much of the online debate considered in our social media study focused not on the principle of cycle lanes or low-traffic neighbourhoods, but on whether local people felt they had been consulted properly. Listening to communities can make the difference between a scheme being welcomed as a local improvement or rejected as a top-down imposition. This should involve everyone and not just the loudest.

Wouter Poortinga receives funding from ESRC, NERC, EPSRC, Welsh Government, and European Commission.

Dr. Dimitrios Xenias receives funding from ESRC, UKERC, and the European Commission.

Dimitris Potoglou receives funding from EPSRC and the European Commission.

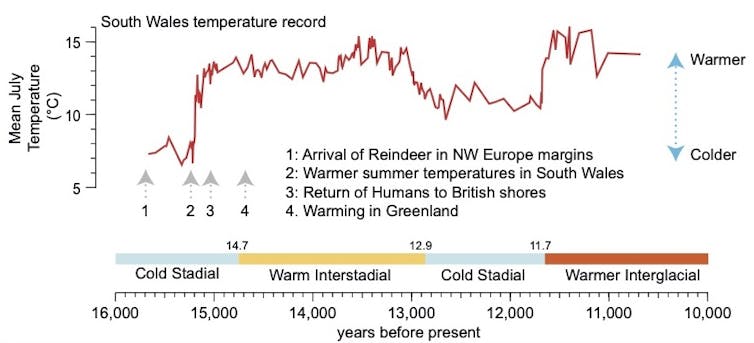

The return of humans to the British Isles after the end of the last ice sheet, which covered much of the northern hemisphere, happened around 15,200 years ago - nearly 500 years earlier than previous estimates.

This movement of people coincided with a sharp rise in summer temperatures in southern Britain, research by our group shows.

These environmental conditions allowed humans to migrate back up into Britain - then still connected to the European mainland. They were hunting herds of reindeer and horses, which were migrating northwards into ecosystems that supported their preferred food for grazing.

After the end of the last ice age, the climate in north-west Europe shifted from cold to warm conditions on at least two occasions, with changes in temperature thought to have occurred over decades.

Our latest research addresses the first of these transitions in the Late Upper Palaeolithic period (14,000 to 11,000 years ago). In areas such as north-west Europe, including where the British Isles are today, humans successively abandoned and then returned to areas at the abrupt transitions between cold and warm periods.

Broadly, evidence of humans from fossil records showed them migrating to where the environmental conditions supported their survival.

Reasons for repopulationThe repopulation of the British Isles after the last ice age is an excellent period to explore the relationships between climate and environment, and the reappearance of humans in this region.

In previous studies, the evidence has been somewhat difficult to read due to uncertainty of the dating methods and incomplete records of environmental and climate conditions. The traditional view had been that the north-west European climate warmed from ice-age temperatures around 14,700 years ago, and humans reoccupied Britain at that time.

However, revised preparation techniques in the early 2000s for the dating of human remains and associated artefacts showed the earliest appearance of humans occurred prior to the warming of 14,700 years ago.

This finding was difficult to understand, as it coincided with what were then considered cold glacial climates that would have been unlikely to support the resources people needed to survive in Britain.

Summer climate record from Llangorse Lake, Wales

Graph shows the timing of returns to British Isles of reindeer and humans after the last ice age, and related temperatures in Llangrose Lake.

Author's own illustration

Graph shows the timing of returns to British Isles of reindeer and humans after the last ice age, and related temperatures in Llangrose Lake.

Author's own illustration

Our study used new calibrations of radiocarbon ages that confirmed the age of those human remains to between 15,200 and 15,000 years ago. So, if humans really were present in the British Isles, could they have survived in cold climates - or was our picture of past environments at this time incorrect?

Clearer insight came from Llangorse Lake (Lake Syffadan) in south Wales, where the lake sediments spanning the last 19,000 years record the abrupt climate change in detail. In addition, the lake's location lies close to the cave in the Wye Valley where the earliest British evidence for human remains after the ice age were found.

By extracting fossil pollen, chironomids (non-biting midges) and chemical analysis of the lake sediments, an unexpected picture of the climate emerged - one that showed previous climate reconstructions for the region were incorrect.

The chironomids were used to reconstruct summer temperature, and this showed the climate warmed in a different pattern than has been identified in other parts of north-west Europe and Greenland. An abrupt temperature shift from 5-7°C to 10-14°C occurred at 15,200 years in Britain - 500 years earlier than previous evidence had suggested.

Just prior to this climate warming, the presence of human prey, such as reindeer and horses, is more consistently detected in southern Britain around 15,500 years ago. These animals were exploiting the newly available grazing grounds, with people tracking the herds northwards and enduring the moderately warmer summer climatic conditions.

Examining archaeological records along with environmental and climatic archives allows more precise reconstructions of when humans were able to repopulate previously inhospitable regions. This is helped by re-evaluating old radiocarbon dates of human evidence in the landscape, and by generating more precise environmental records from the time - including more precise timings of the transitions from cold to warm periods.

This provided us with a fuller picture of human responses to changes in temperature (and their impact on the environment) in the Late Upper Palaeolithic period. Human survival was the driver of these movements, and following prey into new areas was important. But only a relatively small change in summer temperatures was required to enable this migration.

Our research provides better understanding of human behaviour and resilience to climate change after the last ice age around 15,000 years ago. But understanding these environmental triggers from the past helps create new perspectives on human responses to them even now.

These basic factors have not gone away. The response observed in this study might provide clues on future human behaviour as our polar regions warm and glaciers melt, showing how the potential for human migration could be increased.

Adrian Palmer receives funding from Natural Environment Research Council. He is affiliated with Royal Holloway, University of London and Quaternary Research Association.

Around 40% of online shopping globally is driven by impulse buying. JadeThaiCatwalk/Shutterstock

Around 40% of online shopping globally is driven by impulse buying. JadeThaiCatwalk/ShutterstockOnline fashion retailer Asos recently introduced additional fees for customers who return lots of items, marking a significant shift in the fast fashion model that has relied on free, frictionless return policies as a key competitive advantage.

And now the fashion retailer has introduced a new tool to show shoppers exactly what their return rate is, and if they are about to incur a fee. The new policy is aimed at encouraging shoppers with the highest return rates to cut back.

It's not clear yet if other fast fashion brands such as H&M, Shein, Zara and Primark might follow Asos's lead on returns, and whether it will change shopping habits.

There are two common fast fashion shopping scenarios. The first is where customers buy three or four versions of the same item in different sizes, then return the ones that they don't want. The second is where a shopper will buy three or four completely different dresses, for example.

The first approach, called "bracketing" in the retail industry, may be affected more by the new cost of returns. So it may encourage some shoppers to cut down on the sizes they order, perhaps from four to two, if they continue to use Asos. This may have somewhat of a positive environmental effect, if it reduces the size of orders.

The second scenario, impulse buying, generates almost the 40% of all online spending globally, with clothing being the most frequently purchased category. But when faced with return fees, impulse buyers are significantly more likely to avoid the return process entirely, if it is seen as complicated or pricey.

A study in the US found 75% of online consumers have kept unwanted items due to complicated or expensive return processes, rather than initiating a return. This means instead of items going back to the online shop (where they can potentially be refurbished and resold), they remain in consumers' homes or end up in local landfills.

Rather than reducing overall consumption, the return fee merely shifts the waste burden from the retail supply chain to individual households and council waste systems.

However, Asos says it is committed to sustainability. Its corporate strategy states that: "We recognise our responsibility for reducing our impact on the environment and protecting the people in our supply chain." Meanwhile, Shein says: "We are working hard to drive continued progress toward our sustainability and social commitments."

The environmental implications of Asos's new policy, and fast fashion generally, reveal a complex picture. To understand what they are, we need to examine what happens to unwanted clothing in our fashion system, and what incentives genuinely drive more sustainable outcomes.

The returns problemThe textile sector is a significant contributor to global carbon emissions, accounting for 8-10% of worldwide emissions - surpassing the combined carbon footprint of aviation and maritime shipping. Within this broader impact, product returns create additional environmental damage through a cascade of effects: extra transportation, packaging waste, energy-intensive inspection and sorting processes, and ultimately disposal.

The costs of fast fashion to the environment are high.When an item is returned, it enters a reverse logistics system (sending goods back from the customer to the retailer) that is far less efficient than the original chain from manufacturer to supplier. Returns often require individual courier pickups, adding transportation costs and emissions.

So on the surface, return fees appear to offer a straightforward solution: discourage returns, reduce transportation emissions, ease the burden on waste systems. But this logic fails to account for consumer behaviour when faced with financial penalties.

Garments languishing unworn in closets represent entirely wasted resources: all the water, chemicals, energy and labour invested in their production yield no value. Discarding an item of clothing locally just shifts the burden to council waste systems that are often unprepared to handle textiles.

Return fees, in other words, don't necessarily solve the waste problem. They simply reduce consumers' options, sometimes forcing them towards worse alternatives.

This reveals a deeper truth: the environmental problem isn't returns but rather fast fashion itself. The system generates excess production by design. Retailers prefer inventory buffers to avoid being out of stock. This excess is fundamental to how fast fashion operates.

What would make a big differenceCharging for returns is unlikely to improve environmental outcomes that much. The following measures could be more effective:

Extended producer responsibility: In France, retailers are required to finance their collection and sorting systems, creating incentives to design more durable products and manage end-of-life properly. This shifts responsibility from consumers to producers, where it belongs.

Taxation on hazardous materials: Sweden's proposed tax on clothing containing harmful chemicals targets the production phase, where most environmental damage occurs.

Investment in recycling infrastructure: Research clearly shows that viable textile-to-textile recycling at scale is the bottleneck. Without it, reuse becomes the only circular option.

Design standards: Polyester blends complicate recycling. Requiring higher recycled content percentages or limiting fibre blends would address some root causes of waste.

Transparency in returns data: Multiple studies show that retailers lack basic data on where returned items end up. Mandatory disclosure of what they do with returned items would expose the destruction problem and increase their accountability.

The path to greater sustainability in fashion probably isn't through discouraging returns. It's more closely tied to changing how clothing is designed, manufactured and valued. The real question isn't whether returns should cost money - it's why we're producing products no one wants to keep in the first place.

Anastasia Vayona is affiliated with Bournemouth University and ReUse Foundation in volunteer bases

Sam Thomas A/Shutterstock

Sam Thomas A/ShutterstockIn January some people start the year by trying to eat fewer animal products. Veganuary, as the campaign is called, began in 2014 and now attracts 25.8 million people worldwide.