St Valentine

The moment I met you

I immediately knew,

I met my soulmate,

You are sent by Fate…

©Dessy Tsvetkova

picture Nick Victor

Japanese noise is often talked about as if it is one thing, a single wall of sound, a fixed idea. That is not how it really feels when you spend time with it. It is messy, personal, awkward, funny, tiring, and sometimes deeply moving. It grew from real places and real people, not from theory or fashion. To understand it, you have to accept that it does not always want to be understood. Why should it?

Noise in Japan did not appear because musicians wanted to shock people in Europe or America. It came from small rooms, cheap gear, and a sense that normal music was not enough. In the late seventies and early eighties, there was already a feeling that rock music had reached limits. Punk had opened a door, but for some people that door was still too narrow. They wanted sound without structure, without songs, without a clear message. After the rapid growth of cities and technology, sound became part of daily stress. Trains, adverts, crowds, machines, all fighting for attention. Noise music felt like a mirror of that life, but also a way to take control of it. By choosing noise, artists could shape chaos instead of just suffering it.

Even before what most people call noise, there were important earlier examples in Japan that set the ground. Groups like Taj Mahal Travellers in the early seventies explored long drones, outdoor performances, and sustained sound that blurred the line between music and environment. Their recordings and performances treated sound as something physical and shared, not something to consume. This way of thinking mattered deeply and later fed into noise, even if the sound itself was often quiet and slow. Was this already noise in spirit, even if not in volume?

Another crucial early figure is Kaoru Abe. Although usually described as a free jazz saxophonist, his late recordings and performances push so far into intensity and abstraction that they clearly belong to the roots of Japanese noise. His solo performances were relentless. Screeching tones, circular breathing, physical exhaustion, and complete refusal of comfort. Albums recorded shortly before his death feel raw and unfiltered, as if the sound might collapse at any moment. Abe treated sound as a form of total release and pressure, not communication. This attitude had a deep influence on later noise artists who valued commitment and risk over control and polish. How far could a single sound be pushed before it became something else entirely?

Masayuki Takayanagi was one of the early Japanese noise musicians who seemed less interested in pleasing people and more interested in telling the truth, even when it hurt. His noise was not about chaos for its own sake. It came from a deep urge to strip music back until only raw sound was left. Guitars screamed, cracked and fell apart in his hands, but there was focus behind it, not carelessness. Listening to him can feel uncomfortable, even tiring, yet it also feels honest. He treated noise as a way of thinking out loud, a way to push against rules that felt too small. Takayanagi did not try to explain his music much. He played, and let the sound argue for itself.

This early period connects strongly to the wider Japanese avant garde. Experimental music, theatre, dance, and visual art were deeply intertwined. Artists were less interested in categories and more interested in breaking habits. Sound was part of a larger push to reject comfort and expectation. Noise did not arrive from nowhere. It grew out of this avant garde culture, where failure, discomfort, and excess were seen as useful tools rather than problems.

Les Rallizes Dénudés are another vital part of this story. Often labelled as psychedelic rock, their live performances were built around overwhelming volume, endless feedback, and repetition that pushed beyond songs altogether. Recordings from their live shows feel unstable and obsessive. Guitars dissolve into pure sound. Time stretches until it almost stops. Many later noise artists took this idea of feedback as a main voice directly from them.

Keiji Haino stands as a bridge between early experimental music and noise. His early work with Lost Aaraaf, and later solo performances, showed an intense focus on extremes. Screaming vocals, distorted guitar, long silences, and sudden eruptions all appear. Albums and live recordings from the seventies and eighties feel ritualistic rather than musical in a normal sense. Even when melody appears, it feels fragile and threatened. This emotional intensity influenced many noise artists who cared less about sound alone and more about total commitment. How far could expression be pushed before it stopped being music?

Some of the earliest Japanese noise grew close to performance art and underground theatre. Groups like Hijokaidan are a key example. Their early shows were chaotic events rather than concerts. Broken glass, shouting, feedback, body movement, and confrontation were all part of the sound. Albums such as their early live recordings capture this feeling clearly. They do not sound planned or refined. They sound like events barely under control. That sense of danger mattered. It was not about making records that lasted forever. It was about presence and risk.

Incapacitants deserve special attention, and they deserve serious praise. They are not just influential. They are truly great. Their work represents one of the highest points of Japanese noise. Toshiji Mikawa and Fumio Kosakai approached noise with rare focus and intelligence. There is nothing careless in their sound. Albums like Feedback of NMS, As Loud As Possible, and their many live recordings show an incredible sense of balance between force and control. The sound is dense, crushing, and physical, yet carefully shaped over long stretches of time.

Mikawa's electronics create thick, suffocating layers that feel almost architectural, while Kosakai's use of feedback and signal chains adds movement and tension. Together they build noise that feels alive, not static. Changes happen slowly, but they matter. Listening to Incapacitants feels like being locked inside a vast machine that breathes and shifts around you. Few noise acts anywhere achieve this level of discipline without losing intensity. They prove that noise can be overwhelming without being sloppy, and extreme without being empty. How many noise projects sustain this level of quality for so long?

Hanatarash moved in another direction entirely, toward physical danger and confrontation. Their performances became known for using heavy machinery, power tools, sparks, and real destruction. Bulldozers, concrete, and metal were not stage props. They were sound sources. Recordings like Hanatarash 3 still carry this sense of threat. Even without seeing the performances, the recordings feel unstable, as if the sound could collapse at any moment. The question of whether this was music hardly matters. What mattered was the refusal to separate sound from action.

Projects connected to this confrontational spirit also include Niku-Zidousha. This group pushed noise toward raw aggression and physical pressure, often mixing distorted electronics with violent repetition. Their recordings feel blunt and hostile, with little interest in balance or comfort. Niku-Zidousha fit naturally into the Japanese noise world, but they also echo the wider avant garde idea of sound as an attack on the listener's expectations. Is endurance part of listening here, or is it the entire point?

Japanese noise often developed outside normal music spaces. Small galleries, basements, temporary venues, and illegal spaces all played a role. Many artists had no interest in careers or recognition. They made work because they felt driven to do it. Tapes were duplicated by hand. Covers were drawn, painted, cut, or photocopied. Labels like Alchemy Records helped spread this work, but everything remained close to its source. The physical object mattered as much as the sound inside it.

It is impossible to talk about Japanese noise without mentioning Merzbow, but it is also hard not to feel tired of that name. He has become a symbol that overshadows everything else. For some listeners, he is Japanese noise. That is a problem. His work often feels like excess without direction. Endless layers of distortion pushed to the same limit again and again. After a while, the impact fades. Loud becomes flat. Shock becomes routine. When attention stays fixed on Merzbow, it hides how careful, varied, and thoughtful much of the scene actually was.

There is also something uncomfortable about how Merzbow is often treated as a hero. The idea of the artist who goes further than anyone else, who destroys sound completely. This turns noise into a competition. Who is louder? Who is harsher? That misses the point. Noise was never about winning. It was about finding new ways to exist in sound. When everything is pushed to the same maximum, nothing has space to matter. Is destruction really enough?

Many other Japanese noise artists explored very different ideas. Masonna is a strong example. His work combines harsh noise with screaming vocals, sudden silences, and sharp changes. Albums like Spectrum Ripper and his many live recordings feel frantic and unstable. There is fear, humour, and absurdity mixed together. The music constantly shifts, refusing to settle. This nervous energy makes his work feel alive in a way that static noise often does not.

KK Null, both solo and with Zeni Geva, brought a heavy physical weight to noise. Thick guitar tones, repetition, and rhythm play a large role in his work. Albums like Desire for Agony and later Zeni Geva releases balance noise with pounding structure. The sound feels solid and relentless, showing how noise could merge with metal without losing intensity.

There is also a quieter side that people often ignore. Sachiko M is essential here. Her use of sine tones and near silence reduces sound to its smallest elements. Tiny shifts become huge events. Listening demands patience and focus. In the context of Japanese noise, this approach makes sense. It is still extreme, just in a different direction. It challenges the listener through attention rather than force.

Government Alpha explored another path, combining harsh electronics with movement and flow. Albums like Venomous Cumulonimbus Cloud feel less like walls of sound and more like evolving environments. The noise rises, falls, and mutates slowly. It invites long listening rather than immediate reaction.

Other important artists deepen this picture further. The Gerogerigegege used noise, tape manipulation, and provocation to attack ideas of taste and decency. Their releases feel confrontational even before you hear the sound. Astro combined noise with psychedelic repetition, creating trance like chaos. K2 pushed electronics into brutal, metallic forms that feel mechanical and inhuman. Aube focused on single sound sources, like water or metal, building entire albums from one material. This focus shows how conceptual Japanese noise could be without losing intensity.

Japanese noise is often linked to ideas of extremity. Louder. Faster. More brutal. This idea is partly true, but also lazy. Yes, volume matters. Physical impact matters. But there is also control, patience, and detail everywhere. Long stretches of near silence. Repeated textures that slowly shift. Small sounds that feel more intense than any blast of volume. People who say it is just loud do not listen very closely. Are they really listening at all?

Another important part of Japanese noise is how it connects to daily life. There is often a sense of routine in it. Repetition. Mechanical action. Labour without release. Instead of escaping this feeling, noise leans into it. It turns pressure and frustration into sound. That can be difficult to sit with, but it can also feel more honest than polished music designed to comfort. Why look away from this reality?

The way noise was shared also matters. Tapes, burned CDs, handmade covers. Small labels run from bedrooms. This created a loose community, even if the music itself felt isolating. You knew someone had taken time to make this object and send it to you. It was slow, fragile, and imperfect. That fits the sound perfectly.

Over time, Japanese noise became an export. Foreign labels and festivals picked it up. Writers framed it as something exotic or extreme. This changed how it was heard. Some artists leaned into that image. Others faded away. When noise becomes a product, it loses some of its danger. It becomes safe to admire from a distance. Is that what this music was ever meant to be?

Today, Japanese noise still exists, but it feels quieter in a strange way. Not in volume, but in attention. The internet has flattened everything. Harsh sound is easy to find now. Anyone can make it. That makes shock harder, but maybe shock was never the core idea. What still matters is intent. Why make this sound? Why now?

Japanese noise, at its best, asks difficult questions. How much can you take? What do you ignore every day? What happens when you stop trying to please? It does not always give answers. Sometimes it gives nothing at all. That is fine. Not everything needs to be useful.

If you only know Japanese noise through a few famous names and extreme records, you are missing most of it. The heart of it is smaller, deeper, and stranger. It lives in moments that feel pointless and overwhelming at the same time. It does not care if you like it. It does not care if you understand it. That refusal is where its real power sits.

.

Ade Rowe

.

their victims grow up

find their voices

refuse to bind themselves

with shame

that is not theirs.

Sooner or later

girls become women

reach out to others

share their stories.

Sooner or later

the lies unravel,

the hiding places fall apart

and they will be judged.

Sooner or later

the women will speak.

And women everywhere will say

we will hold you to account

and you will pay.

Tonnie Richmond

.

Richard Reeves

Inspired by the elements of nature, this abstract animation film explores the element of light through optical sound and projected images painted directly onto film.

Director: Richard Reeves

Animation: Richard Reeves

Production: Flicker Films

Animation Sound Design: Colin Kennedy

.

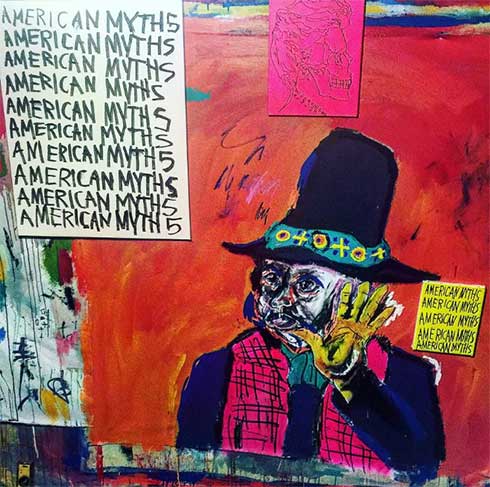

the return of, The Fleeing Villagers (Fred Lonberg-Holm)

Convergência do Vôo, Fred Lonberg-Holm / João Madeira / Bruno Pedroso / Carlos "Zíngaro" (4daRecord)

Transgressive Coastlines, Caroline Kraabel / Pat Thomas / John Edwards / Steve Noble (Shrike Records)

LliFT #18, Llift (Recordiau Dukes)

Based in the San Francisco Bay area, Fred Lonberg-Holm is an American cellist or, as he's described himself, anti-cellist. He studied with Anthony Braxton and Pauline Oliveros among others and is most well-known for his work in free improvisation and jazz, although he's also worked as a session musician and arranger with rock, pop and country artists. His latest release, the return of by The Fleeing Villagers, is a savage collage, a punk/noise juggernaut of an album which holds a mirror up to the current state of the USA. You've been warned. I like it and, indeed, it deserves to achieve some sort of cult status. He also figures on another recent release, a collaboration on the 4daRecord label which is, let's just say, a more sedate affair. The title, Convergência do Vôo translates as 'flight convergence'. It describes a meteorological phenomenon, much prized by glider pilots, whereby two air masses meet, forcing air to rise and thereby enabling gliders to gain altitude. I guess it's intended as a metaphor - and it's a good one - for the experience of improvising as part of a group. On it, Lonberg-Holm loops the loop - not for the first time - with fellow string players João Madeira and Carlos "Zíngaro". As a trio of string-players they've made at least a couple of albums in the past on which they've collaborated with a fourth musician (one features Swiss guitarist Florian Stoffner another, bass clarinettist José Bruno Parrinha). On this occasion, they're joined by drummer Bruno Pedroso.

A classically-trained violinist, Carlos "Zingaro" has worked with Derek Bailey's Company and has appeared on over fifty recordings. Bass player and founder of the 4daRecord label, João Madeira, has conducted research into fado (a form of traditional Portuguese music) and worked across many genres, although his main focus is on free improvisation and composition. Bruno Pedroso has been involved in jazz drumming since 1995. As well as teaching, he's very active as a freelance performer.

The guy credited with the mixing, Gordon Comstock, deserves a mention, too. A balance between the instruments has been achieved which allows all kinds of textural nuance to come through. And there's plenty of it, even though the music is often - but not always - fast-paced and dense. There's a lot of subtle shading going on, and, as I hear it, there's an improbably lyrical edge to it. Pedroso's drumming effortlessly joins in the conversation, creatively seeking out - and finding - common ground with the strings in ways I imagine you could only achieve by actually doing it in real time and, indeed, there's a sense of seat-of-the-pants discovery to the music which adds to it's forward drive.

Transgressive Coastlines, the latest release - at time of writing - from Shrike Records, brings together the formidable quartet of Caroline Kraabel, John Edwards, Pat Thomas and Steve Noble. Born in Seattle, Kraabel moved to London in her teenage years and has been a fixture in the free improvised music scene ever since. For almost five years, she had her own programme on Resonance FM, Taking a Life For a Walk, in which she wandered the streets of London with her sax and her children. Among other large-group compositions, she created, for the South Bank Centre, Saxophone Experiments in Space, a 'site-specific ambulant composition for 55 saxophonists'. She's also been involved with the London Improvisers Orchestra and, in addition, has regularly worked as half of a long-standing duo with bassist John Edwards. Obsessed with sound from an early age (his brother played the drums, which intrigued him), Edwards took up the bass guitar in his teens, switching to the double bass in his twenties. He's played with likes of Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, Lol Coxhill and Peter Brötzmann among many others. He's said of improvisation: 'the establishment - by which I mean people in offices, suits and government - maybe want people to do nothing. They want to keep people drugged up with the banal, working, doing the same thing. Maybe free music upsets that'. Pat Thomas began playing the piano when he was eight and started to play jazz piano in his teens. He went on to develop a style of his own, drawing on free jazz, improv and new music. As Rae-Aila Crumble put it on Bandcamp Daily, 'The music he releases is both transcendent and grounded, rooted in his Muslim background and fascination with Islamic mysticism, as well as the histories of jazz afronauts like Sun Ra. Browsing through his … catalog feels like tapping into the secrets of the universe, similar to the way jazz historians describe Coltrane's discography as always searching for something.' Drummer Steve Noble got his first drum kit when he was twelve. He was mainly self-taught, but then, as he explained in an interview with Chris Searle for the Morning Star, 'In 1979 I met Nigerian drum master Elkan Ogunde and we played many concerts [and] workshops together - a great learning experience. By the mid-80s I was organising concerts and festivals and performing with Sheffield guitarist Derek Bailey, another huge influence'. Since then, he's worked with a wide range of musicians and toured extensively throughout Europe.

Like that of the album, the two-word titles of the three tracks on Transgressive Coastlines all suggest surrealist word-play. In the first track, 'Dark Rainbow', the quartet create a complex texture that veers between the polyphonic and the pointillist. You could think of the musical colours here as a rainbow - there are dazzling moments of bright light - but there are others in which the music reaches a point of near stasis which might be thought to invoke the visual impossibility of the title. At first fragmentary, the music of the second track ('Volcanic Tears') gradually becomes more dense. The musicians trade explosive gestures which build into something more sustained, at times static, even, only to be sent off in new directions by further explosive activity. The third track ('Diamond Ashes') again begins with fragmentary explorations, but this time the music settles into a sustained monolith of sound. A pulsing chord from Pat Thomas within it becomes increasingly distinct, transforming the monolith into a series of repeated chords. It finally comes to an end, but no-one seems to want to move away from the zone they've created. The repeated chord idea makes a comeback and the sax, bass and drums continue to pursue their close but inventive orbits around it.

Listening to it all for a second time, I was struck by the sheer virtuosity. Of course, virtuosity isn't essential to good music (it can even become a substitute for real content), but you get a real sense listening to this that you're listening to four seasoned musicians in total command of what they do while, at the same time, still finding fresh and inventive things to say.

Which brings me on to LliFT #18. Just to remind us, LliFT are an 'inclusive community group giving individuals the opportunity to play freely improvised ensemble music on a regular basis in North Wales'. It's only a few weeks since I was writing about #17, saying how it was one of the best LliFT albums yet. #18 carries on where #17 leaves off. One might think that after an outfit putting out so many albums in quick succession, one might detect a note of tiredness, a drop off in quality. Nothing, however, could be further from the case. What we have here is well over an hour of immersive musical landscapes packed with creativity. Listening to it, I was reminded of M John Harrison's Light Trilogy: not only on account of the enthralling strangeness of both, but on account of a striking passage in which the book describes how different civilisations living in different parts of the galaxy developed space travel independently of each other: 'Every race they met on their way through the Core had a star drive based on a different theory. All those theories worked, even when they ruled out one another's basic assumptions. You could travel between the stars, it began to seem, by assuming anything.' What he says about space travel here could also, in many ways, be said about the world of improvised music. People navigate musical space with often very different musical 'star drives': you can, for example, put together a small group of the most experienced improvisers (as in the case of TC), or, like LliFT, create an 'inclusive community group'. Neither is a recipe for success or failure, although, in the case of the albums here, both more than succeed.

Dominic Rivron

LINKS

the return of: https://fredlonberg-holm.bandcamp.com/album/the-return-of

Convergência do Vôo: https://joaomadeira.bandcamp.com/album/converg-ncia-do-v-o

Transgressive Coastlines: https://shrikerecords.bandcamp.com/album/transgressive-coastlines

LliFT #18: https://recordiaudukes.bandcamp.com/album/llift-18

.

It might be a dream repeated, unclear in its own right, perhaps within a dream held from another night, wild with words but always coherent for opening doors in that world. Tenses get muddled up, and a long sequence of numbers will surely mean a winning lottery ticket in the morning, or temptation to join you in bed.

Asked with gravitas to remember a name that makes perfect sense in the present night, and that will be Googled tomorrow with little result, I still hope to dispel blurriness, plead with turbulence and dispersion. "Paradisial" retains the original inflection, but we wise people think "heavenly" preferable to ignite the erotic in a subtitle.

On a summer stroll, we will be gifted the sound of birdsong and the very last pear blossom. With joy and relief, we will finally hear what they sing of and mean, their lyrics of two regular syllables or more. I will create a new season just for sleep, for a space where I do not have to repeat myself, to not have lips follow mine in silent imitation, not to be counted on fingers one, two, three, as if I and larger figures needed to be contained. Ah, to be seen in my language, from my best side!

Melisande Fitzsimons

Picture Rupert Loydell

.

Alan Dearling writes:

A great celebration of live music at a great Independent Music Venue. The Pale Blue Eyes' gig at the Grayston Unity in Halifax created an almost perfect marriage of music. First up, Warm Parts provided a wall of sound, a dark undertow of Kraut-rock styled drum-driven intensity. In my mind's eye I was taken back to the late 1960s when Hawkwind wereAlan Dearling blowing minds with pummelling, psychedelic waves of sound. Warm Parts received an enthusiastic response from the nicely packed crowd, which is not always the case for support bands. They are certainly continuing and sustaining their musical journey into the oeuvre of outsider, psychedelic weirdness - noise-rock a little akin to bands such as Wooden Shjips.

Rachael explained to me: "The band was conceived in early 2024 by myself, Rachael Elwell (synths, programming, theremin and visual artist), and I quickly recruited Dan Smith (guitars), who had moved in similar musical and creative circles, performing in various DIY and experimental bands in and around Manchester in the early 2000s. With the sound evolving and a shared desire for having live drums, we were introduced to Bryn, who, after hearing some early rehearsal recordings was keen to add to the group. With his shared musical background and style he quickly became an integral part of the band's ever evolving sound."

Warm Parts suggest that these are online sites where you can hear Warm Parts' 'Special Square' EP (these are not clickable links):

The Pale Blue Eyes arrived on stage. They are mesmerising, professional, polished, offering propulsive rock music with a high melodic content, whilst providing quite an adrenalin rush…

Matt Board is a suitably charismatic front-man and singer with PBE, who already have a significant fan-base and much support from BBC Radio 6 Music. Matt and myself have met up before, back in the halcyon days of music in Devon's town of Teignmouth, during the advent of Muse and the other local favourites, The Quails.

Pale Blue Eyes say that they are:

"Born of a cross-pollination between Totnes and Sheffield, Pale Blue Eyes have been steadily grafting over a number of years to exact their modernist pop vision.

At the ship's helm, Matt and Lucy Board are a genuine marriage of two stylistic perspectives, each bringing unique sonic tropes to the table.

It is the pair's fascination with DIY ethic, retro synths and reminiscence that truly fuels their sound world, calling upon nostalgia and a captivating optimism.

The third part of the Pale Blue Eyes triad arrived when Matt and Lucy met bassist Aubrey Simpson at South Devon's Sea Change festival.

Together they've made three albums, with several tracks from the albums playlisted at BBC Radio 6 Music. They've played three Riley sessions, toured extensively in the UK and Europe, supported GOAT, Slowdive, Sea Power, The Editors, Public Service Broadcasting, The Midnight, FEWS and more…

The band released their third album in March 2025 on their own imprint, Broadcast Recordings. As with the first two albums the record has been produced by the band and finally mixed and mastered by Dean Honer. Honer has produced the likes of The Human League, Add N to (x) and Roisin Murphy and worked with countless Sheffield names from Jarvis Cocker to Tony Christie."

On the current live dates, producer and musician, Lewis Johnson-Kellett joins the trio of Pale Blue Eyes on guitar and synths/keys.

Live video: https://youtu.be/0SFd5nkpFoU

Online, Stephanie Pipe recommends Pale Blue Eyes:

"…saw them when they were on with Public Service Broadcasting a couple of years ago. Blew me away. Bought several cds and merch and am excited to see them back in Sheffield again soon…"

Pale Blue Eyes add: "Thanks to Marc Riley and Gideon Coe for including our track 'The Dreamer' in their best of 2025 show on BBC Radio 6 Music in amongst some class tracks! Cheers to them, and to those who tune in."

It was a great event to celebrate the importance and cultural contribution of the UK's Independent Venues.

'Signify'…jangling, guitar pop with disembodied vocals…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vbf6EsAf8ag

'The Dreamer' (2025) …A thing of Floating effervescence… Official video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUbdIWLpGls

'New Place' film about making their PBE third album (2024):

My favourite baby Jesus painting is the one of Mary

in her halo giving him a spanking in front of witnesses

by Max Ernst, the German, who helped found Dada

and became involved with Surrealism, quietly distancing

himself without rancour and being interned by the Nazis

when they invaded France and escaping to America

where he met up once again with Andre Breton and

Marcel Duchamp, briefly married Peggy Guggenheim

before going back to Europe, and becoming more abstract,

lyrical. I've met none of them. Not Max, Marcel or Andre.

Jesus, Mary, Peggy. Although I've read accounts. Seen

some photographs. Had clever thoughts. In the painting,

the baby Jesus is big and blonde and Aryan. His mother,

I imagine, is trying to beat some sense into him. At least

that's my understanding. The three witnesses

appear aloof, disinterested. Only present for posterity.

Andre Breton, Paul Eluard (the poet), Ernst himself.

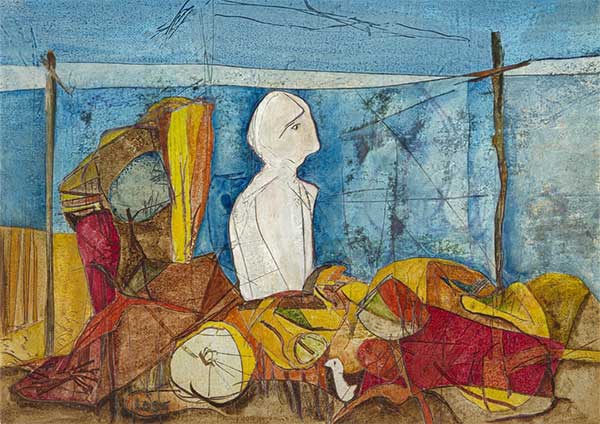

Steven Taylor

Picture Max Ernst

.

Tales from Topographic Oceans, Yes (Super Deluxe Edition: 12 CDS + 2 LP + blu-ray box set)

You just couldn't resist it, could you?

Umm, no. What?

Another reissue… The same old crap repacked for susceptible drongos like you.

It's not the same old crap, it's got new remixes, new versions, new recordings of works-in-progress and - finally - some live recordings of Yes' greatest, well one of their greatest, albums.

Waddya mean 'finally some live recordings'? I've seen your bloody CD shelf, loads of bootleg downloads. Surely you've got them already?

Well, yes, no. I mean, the ones I've got are actually better… and complete, but they weren't in Steve Howe's tapes library so they're not in the box. It's nice to have some official cleaned-up versions.

So nice you have to buy a 12 CD box?

Well, I like having the official stuff.

Even if that bloke Steve Wilson gets to mess it all up with his remixes?

Well, I shan't be playing those much. Or the instrumental versions he has done. Or the single versions.

Single versions? I thought the whole idea was to bore you into a mystical state through duration and repetition? Peak hippyshit.

Well, I wouldn't put it quite like that.

What would you put it like then?

Look, I explained this to you last time, Tales from Topographic Oceans is a double album based on a footnote in Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. Jon Anderson, the singer, and Steve Howe, the guitarist, composed the initial suites of music at night on tour, and then the band all worked on it together.

But we all know it's boring as fuck. I mean Rick Wakeman dissed it from the word go, and it's renowned as overlong and overambitious.

But it's that ambition that makes it stand out, makes it unique. I mean, who else was releasing spiritual stuff like that?

Well thankfully, nobody else. One band is enough.

You're just ignorant. A bit of spiritual insight, too much wonder or magic and you run away scared.

At least I don't end up buying massive box sets full of stuff I already have.

And remixes and live tracks.

That you won't ever listen to again.

Maybe. Maybe not. And there's talk of them doing Relayer next in the box set series.

Woohoo. For goodness sake Johnny, reign it in. You spend more on box sets and reissues than beer.

That's a good thing isn't it?

Not in my books. Pub?

Oh, ok then. Can you carry this though, this box set is bloody heavy.

Ok, but it's your round.

Again?

Think of it as an outpouring of spiritual love.

Johnny 'soft summer mover' Brainstorm

.

Nick Drake

CELLO SONG

Strange face

With your eyes

So pale and sincere

Underneath you know well

You have nothing to fear

For the dreams that came

To you when so young

Told of a life

Where spring is sprung

You would seem so frail

In the cold of the night

When the armies of emotion

Go out to fight

But while the earth

Sinks to it's grave

You sail to the sky

On the crest of a wave

So forget this cruel world

Where I belong

I'll just sit and wait

And sing my song

And if one day you should see me in the crowd

Lend a hand and lift me

To your place in the cloud

© Nick Drake

.

Vintage Bus Day, 21st May 2023

Olive single-decker accelerates for Happy Mount

gentle hills beyond the bay, occluded mountains misted out

the panorama undulates a hypnotic content

a summer model of life and tide

all cast below Bare's tall tower

whose distinctive chequerboard exudes the decades passed -

though May blossom recurs forever, we hope

and whitens the greens on the way to Hest Bank

countering the daffodils all gone - and that melancholy shiver:

how many Springs?

Gateways and gardens to Bolton-le-Sands

where the Far Pavilion's exotic dancer, girded with praise

is suppliant for custom.

A white 20s house with a redbrick Plimsoll line

leads the way to a perfect jumble of Metroland

mellow red roof tiles and graceful windows

open meandering pathways in the mind

travelling a century back.

Here the stained-glass oval doorway myths

are undisturbed by the power catenary

which the railway weaves through this sweeping land

shallow rise and fall towards the border

freshened fields in lines of cut grass,

the smell, the greenness, another throwback to the past

but the future is here, we shouldn't waste time thinking of all that is lost

meeting Carnforth with the mind's cross-Channel drift . . .

to Sailly-sur-la-Lys.

Carnforth - twinned with Sailly-sur-la-Lys

© Lawrence Freiesleben, January 2026

.

Please

keep

asking

how

far

down

must

I

go

They

never say

.

John Phillips

Picture Fred Schimmel

Excavating the disenchanted city

by Hari Kunzru

Excavating the disenchanted city

by Hari Kunzru

The North Prospect of the City of London and Westminster (as seen from Parliament Hill), 1712, detail of an engraving by an unknown artist © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A painting depicting the arrival of Brutus to England, the slaying of giants, and the founding of a city, possibly London, fifteenth century, by an unknown artist © The British Library/akg-images

It's not so much where to begin as when, though in London the distinction between time and space broke down centuries ago. There's a cast of wanderers, visionaries, and itinerants, the self-educated and self-published, a long lineage of cranks and outcasts, mostly penurious, always opinionated, stretching away into the mists of pseudohistory. If you go back far enough you end up right at the beginning, with King Brutus, great-grandson of Aeneas, defeating a clan of giants and founding a settlement he named New Troy. The giant Brân the Blessed's head, which spoke for many years after it was severed, lies buried under a white hill, on top of which the Norman conquerors built a fort, known to later generations as the White Tower, or just the Tower of London. The name London comes from the Llandin, a sacred mound now called Parliament Hill. The London. Or perhaps it originates with King Lud, the carnivalesque warrior and giver of feasts who was bold enough to rename New Troy after himself. Kaerlud became Kaerlundein, and eventually London. Of course, if you indulge in such etymologies, you'll find yourself chased down alleyways by angry professors and cornered in the rookeries, the most intellectually disreputable of the city's slums. Nothing about this London, the London, survives the scrutiny of decent folk. It is a hive, a warren, lousy with junkie poets and readers of tarot cards, autodidacts prone to exaggeration and outright deceit.

Brân's head was buried facing France, though some say King Arthur dug it up and threw it into the sea, because he wanted everyone to know that he and he alone was the protector of the island kingdom. Without Brân's watchfulness, it was probably inevitable that the French would sneak across the Channel. You can see them in a grainy photograph taken in September 1960, outside the Sailors' British Society in Limehouse, eight men and a woman, walking toward the camera, dressed in tweeds and overcoats. They are Parisian intellectuals—and not just French; they are Belgians, Dutch, Danes, and Germans, participants in the fourth conference of the Situationist International, an avant-garde group fond of the trappings of bureaucracy, heckling at boozy meetings, and denouncing one another for perceived artistic and political transgressions. They are fascinated by this impoverished district of docks and shabby warehouses, associated in the popular imagination with Asian sailors, white slavery, and cholera. In 1955, some future Situationists had written to the editor of the Times of London, complaining about the redevelopment of the area, which had been pulverized by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz:

It is inconvenient that this Chinese quarter of London should be destroyed before we have the opportunity to visit it and carry out certain psycho-geographical experiments we are at present undertaking.

In the first issue of the publication Internationale Situationniste, "psychogeography" is defined as "the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals." This might sound bloodless, but for the Situationists it was part of a utopian revolutionary program. The small band of café radicals sought to overthrow not just a government but the entire global system, which relied on what they called the "organization of appearances," or simply "the Spectacle." As the explosion of consumer society followed a period in which totalitarian propaganda had mobilized millions for war, they were among the first to understand mass media as a subtler means of social engineering. Advertising, film, television, fashion, and pop music were, they theorized, useful to the interests that controlled them because together they wove a kind of fascinating screen—or Spectacle—behind which the actual operations of power could be hidden. Pacified citizens had been reduced to dazzled consumers, unable to even see what was going on, let alone understand or oppose it. "The organization of appearances is a system for protecting the facts," one member, Raoul Vaneigem, wrote. "A racket."

"Whitechapel High Road, 1965," by David Granick. © London Borough of Tower Hamlets/Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives

Sixty years later, the Spectacle saturates us in ways the Situationists never imagined. Online platforms structure our personal relationships; algorithms nudge us toward the platform owners' preferred choices. "Intelligence" is embedded into everything from our phones to our kitchen appliances. But back in the Sixties, the Situationists saw the physical environment of the city as an expression of the mass society created by consumerism and governed by the Spectacle, and they felt power closing in around them: "All space is occupied by the enemy. We are living under a permanent curfew. Not just the cops—the geometry."

As a teenager growing up in London, I experienced the Spectacle's rapid intensification. I would go out with friends to a burger restaurant in Covent Garden that had video screens on the wall, a stunning innovation in Eighties Britain. In between MTV clips, a camera would roam the room, and we would fleetingly see ourselves onscreen, an experience that felt edgy and utterly modern. Then we would go home on the Tube, waiting on platforms strewn with rubbish because the bins had been removed to stop the IRA from placing bombs in them. Later, after some major terrorist attacks on financial targets, the City of London erected a security radius known as the Ring of Steel. By the mid-Nineties, London was said to have more security cameras than any other city in the world.

In the years when the Ring of Steel was growing around London's financial district, psychogeography was also in the air. Everyone seemed to be interested in exploring the fabric of the city, trying to excavate its strange atmospheres and hidden meanings. I knew people who were teaching themselves urban climbing, trespassing into abandoned buildings as a form of artistic action. Others were involved in an anticapitalist movement called Reclaim the Streets, or were steeping themselves in countercultural histories. My friends and I cycled along canal towpaths and danced at warehouse raves that were advertised on pirate radio stations whose transmitters were concealed on the rooftops of council tower blocks. There was a sense that a change was coming to London. We told ourselves it was the impending millennium, the new thousand-year cycle that the government was celebrating by building a giant dome on the Greenwich Peninsula. In retrospect, I think we sensed that we were living our last moments in the material world, before all our visions migrated online.

Ileft London for New York eighteen years ago. For a long time I didn't miss it. Recently I have found myself thinking about it more often, and sometimes even dreaming about it. In these dreams, I walk down alleyways toward mysterious glowing lights. I wait outside the kind of seedy minicab offices that used to exist before the advent of ride-hail apps. My old friends have moved on; the places I used to know are gone or have passed on to the next generation. I am not nostalgic, exactly, but lately I have been preoccupied by something that I used to believe I had found in London—a city within the city, above and beneath and between the everyday. This visionary city had a history and geography that didn't correspond to the official version. It was a prism, a maze in which I thought I discerned possibilities, things that might have been or ought to have been, or that I could imagine into existence. In the era of GPS and social media, where every location has already been rated and reviewed and nothing is real unless it is captured by a cell-phone camera, is it still possible to fall through the cracks into this other world?

For many years, as I took the train to Portobello, I would pass a giant piece of graffiti running along a wall between Westbourne Park and Ladbroke Grove stations. It had been there since at least the Seventies, long enough to have become a landmark: same thing day after day—tube—work—dinner—work—tube—armchair—t.v.—sleep—tube—work—how much more can you take?—one in ten go mad—one in five cracks up. It was the work of a group called King Mob, effectively the British chapter of the Situationist International until its members were expelled in one of the frequent purges. Malcolm McLaren, future manager of the Sex Pistols, supposedly participated in an early King Mob action. Jamie Reid, the graphic designer who made the famous image of Queen Elizabeth II with a safety pin through her mouth, did the cover for the first English-language Situationist anthology.

A "God save the Queen" button based on the 1977 artwork by Jamie Reid © Mick Sinclair/Alamy

Reid's promotional poster for the Pistols' single "Pretty Vacant" shows two buses, their destinations nowhere and boredom. In "God Save the Queen," John Lydon snarls that there is "no future." With this lyric, he channeled the Situationist critique that shopping and entertainment were somehow substituting for a more vivid and authentic life into the nihilist posturing of punk—but the full line is "there's no future in England's dreaming," which hints at something altogether more romantic and less rational. When Situationism came to London, it fused with a subterranean current of mysticism that flows through the city like one of its "lost rivers," the Fleet or the Tyburn, long since buried under the surface.

In Derek Jarman's 1978 film Jubilee, the punk-scene celebrity Jordan cheekily refers to a Situationist slogan that had appeared on the walls of the Latin Quarter in Paris during the uprising of May 1968.

Our school motto was Faites vos désirs réalités. Make your desires reality. . . . In those days, desires weren't allowed to become reality, so fantasy was substituted for them: films, books, pictures. They called it art. But when your desires become reality, you don't need fantasy any longer, or art.

The end of alienation would mean nothing less than a reenchantment of reality. In the film, Jordan is literally a magical vision. Jubilee opens with Queen Elizabeth I summoning her court magician, Dr. John Dee, to ask him for "some pretty distractions which you call angels." Dee looks into the black depths of his scrying mirror and summons a spirit who grants the queen a vision of the future. The film cuts to a desolate South London street, the sound of machine-gun fire in the distance. A gang of punk girls is beating someone up. Elizabeth II, whose Silver Jubilee was celebrated with much pomp and circumstance in 1977 (giving the film its title), is mugged inside a shed on some waste ground, her crown stolen by feral punks. Transported to the scene, her royal ancestor looks down in horror.

Dee's black mirror is now in the British Museum. As a child, when I wanted to be an archaeologist, the museum was one of my favorite places. My mother would sit outside reading a book while I wandered the halls, visiting the Rosetta Stone or the helmet and sword from the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo. In my twenties, I would sometimes write in the museum's Round Reading Room, a huge open space beneath a dome inspired by the Roman Pantheon. Ghosts of previous readers flitted around the card catalogues: Arthur Rimbaud, Mark Twain, Karl Marx, Marcus Garvey, Bram Stoker, Virginia Woolf. If London had a psychogeographical center, it was not Trafalgar Square or Buckingham Palace but this room, the navel of an imperial treasure house that for more than a century was also a magnet for the kind of oddballs who liked to "do their own research."

A photograph of the Reading Room of the British Museum while under

construction, 1855, by William Lake Price © The British Library/Bridgeman Images

The reading room closed in 1997, and the library moved to new premises on Euston Road. Dee's mirror is easy enough to find, lying in a case with other magical paraphernalia, including a knife used as a prop by a charlatan alchemist, the tip of the blade "transmuted" into gold. The mirror is actually an Aztec ritual object, a polished obsidian disk brought to Europe soon after the Spanish conquest. Small and undramatic, it is the sort of thing that most tourists pass by. I have come back to London to lose my bearings, to lose myself, but all I can make out in its depths is my own reflection. I remember that in real life, Dee saw no angels. It was his assistant, Edward Kelley, who had—or claimed to have—the gift of sight. I am stubborn. I stare harder, bending down in front of the glass case.

The black mirror is where I begin whatever it is I'm doing back in London. An action, a ritual. Perhaps a spell. The Situationists practiced something they called the dérive, usually translated into English as "drifting," an "aimless stroll" that served as a tool for analyzing the "psychic atmospheres that power had produced." "In a dérive," wrote Guy Debord,

one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.

What I have in mind is something like a dérive, except not quite, because I have a general route in mind, about eight miles southeast to Greenwich, the site of the prime meridian, the line of zero degrees longitude that the British Empire invented to divide the world into Eastern and Western Hemispheres. I will connect the museum to the meridian, two sites of traditional power. And perhaps in so doing I will reenchant reality, or at least my corner of it.

In the streets of Bloomsbury, like barnacles on the museum's huge hull, are shops and services catering to the collecting impulses of the habitués of the old library, the men (and a few women) I used to see huddled over their solitary lunches in the local cafés. There are dealers in coins and stamps and antiquities, and, above all, books. At the Atlantis on Museum Street, an occult bookshop that has existed since the Twenties, I am shown a massive volume of transcriptions of Dee's conversations with angels. It must weigh ten pounds. It's an expensive volume, and I have a long way to walk, so it isn't that hard to say no. I put it back on the shelf and wander toward Soho. This is a detour—Greenwich is in the opposite direction—but of course getting to Greenwich is not the point, and it feels somehow appropriate to start out by going the wrong way.

In 1802, seventeen-year-old Thomas De Quincey, the son of a wealthy merchant, ran away from his Manchester boarding school. He made his way to London, where he slept for a while in an empty house on the corner of Greek Street and Soho Square. "I found," he wrote in his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, "that the house already contained one single inmate, a poor friendless child, apparently ten years old." The building where De Quincey and the nameless little girl huddled together under a scrap of rug and an old sofa cover has since been demolished, replaced by a Barclays bank. As I walk past, someone is asleep in the doorway under a construction of cardboard boxes.

At night, De Quincey would wander up and down Oxford Street, a major East-West thoroughfare. Now one of the busiest shopping streets in Europe, it was in the first years of the nineteenth century a zone of pubs and other places of entertainment, notorious as the route that condemned prisoners took from Newgate Prison on their way to be hanged at Tyburn. De Quincey's companion on these walks was Ann, a teenage prostitute whom he portrays as an almost saintly figure, crediting her with saving his life "when all the world had forsaken me." When he left London, he promised to return and help her, expecting to be back in a week. They never saw each other again. Ann was lost in the "great Mediterranean of Oxford Street." For the Situationists, the pair were the Adam and Eve of a new sensibility. As an essay in Internationale Situationniste put it:

The slow historical evolution of the passions reaches a turning point with the love between Thomas De Quincey and his poor Ann, separated by chance and searching yet without ever finding one another . . . through the mighty labyrinths of London; perhaps even within just a few feet of each other.

This was a form of love and loss brought about by the new social relations of the crowded nineteenth-century metropolis. In the twenty-first-century city, things have inverted. It is trivial for runaway teenagers to stay in touch with one another, but hard to escape the eyes of others—security cameras, facial-recognition technology, and all the rest of the apparatus of surveillance and control.

From Songs of Innocence and Experience, copy Y, plate forty-six

(orange-brown ink, watercolor, and shell gold), by William Blake, etching 1794, print c. 1825. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1917, New York City

"If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite." So wrote the poet William Blake, who is a sort of tutelary spirit for London's seekers and visionaries. Blake's birthplace at 28 Broad Street has been obliterated by a brown granite tower, a monument to the worldview of the City of Westminster's postwar planning department, but his influence is everywhere in the other London. One of Blake's disciples was a young Welsh writer who arrived in London in the 1880s and took a job trawling through a garret full of old occult books, writing descriptions for a publisher's catalogue. Too poor to attend university, Arthur Machen received his education through bookselling and publishing. Per Machen, the garret contained volumes on witchcraft, Kabbalah, gnosticism, hermetic magic, and much else that "may be a survival from the rites of the black swamp and the cave or—an anticipation of a wisdom and knowledge that are to come, transcending all the science of our day."

Despite his esoteric interests, Machen grubbed up a career as a popular and prolific author. There is, he wrote, "a London cognita and a London incognita." He considered

the science of the great city; the physiology of London; literally and metaphysically the greatest subject that the mind of man can conceive. . . . You may point out a street, correctly enough, as the abode of washerwomen; but, in that second floor, a man may be studying Chaldee roots, and in the garret over the way a forgotten artist is dying by inches.

Machen's London was a descendant of Blake's, where angels perched in trees. It was intuitive, antirational, a city of visions glimpsed out of high windows and horrors lurking at the end of dark alleyways. "I didn't buy a map," says one of his characters, recalling his journey of discovery. "That would have spoilt it, somehow; to see everything plotted out, and named, and measured."

Farther east on Bloomsbury Way, I steer well clear of the commodified irrationalities of Serendipity Crystal, with its window display of sparkly geodes. I'm looking for the spire of St. George's, Bloomsbury, consecrated in 1730. You can see it in the background of William Hogarth's print Gin Lane, presiding fancifully over the slums of St. Giles. Two lions and two unicorns writhe at the base of a stepped pyramid. On top, instead of a cross, there's King George I, dressed as a Roman emperor. Its architect, Nicholas Hawksmoor, designed six London churches that have acquired a strange reputation. They were designed to have a "Solemn and Awfull Appearance," an aesthetic that the authorities hoped would intimidate the London rabble into faith or, failing that, compliance. Since the Seventies, Hawksmoor, a Freemason and student of ancient Egypt, has been spirited across the border into fiction, reimagined as a sort of dark magus of London, a figure who sought to control the city through architecture, binding it to the will of those he served.

"Hawksmoor was no Christian," says Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria's surgeon, in Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's graphic novel From Hell. Gull is being driven by a coachman on a tour of London, which is marked by various sites of esoteric power. Gradually their route takes the shape of a pentagram. "Encoded in this city's stones," Gull says, "are symbols thunderous enough to rouse the sleeping Gods submerged beneath the sea-bed of our dreams." Gull has been commissioned by Queen Victoria to hush up a royal scandal, but he will exceed his brief and commit the appalling killings ascribed to Jack the Ripper. A psychopathic misogynist and high-ranking Freemason, Gull sees these killings as a "great work," a ritual intended to enforce an ancient patriarchal order. Pyramids and obelisks are sun symbols, and Hawksmoor and his fellow Masons have positioned them round the city. " 'Tis in the war of Sun and Moon that Man steals Woman's power; that Left Brain conquers Right . . . that reason chains insanity." The pattern of spires, obelisks, and pyramids forms a pentacle "wherein unconsciousness, the Moon and Womanhood are chained."

Preparatory drawing (red chalk and graphite on paper, incised with stylus and verso rubbed with chalk) for the engraving Gin Lane, by William Hogarth, c. 1750. Courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum, New York City

Moore is best known as the author of the revisionist superhero series Watchmen and of V for Vendetta, the story of a dystopian near-future London and the source of the Guy Fawkes mask that became the symbol of the Anonymous collective of the 2010s. He is also a practicing ritual magician. Moore doesn't come to London anymore; in fact, he rarely leaves his house in Northampton, the town where he was born. On the phone, he describes to me a "borderland between the world of things that materially exist and the world of things that don't." It is, he says, "a porous borderland, because if we look around us, everything surrounding us started out as an idea in somebody's mind, the chairs we're sitting on, the devices we're talking on, the language we're speaking in, the carpet, the curtains, the view outside. We are living in our unpacked imagination. As I see it, it's the imaginary space which is the foundation of the physical world." I am struck by this. It is an inversion of the generally accepted chain of causality, wherein the material underlies the social and the airy castles of the imagination float somewhere overhead.

In The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot famously described Twenties London commuters as ghostly figures crossing London Bridge "under the brown fog of a winter dawn." His London was an "unreal city" that seems to have migrated out of imagination and into reality, a necropolis watched over by the security cameras of the Ring of Steel. Eliot's ghosts carried on down King William Street to where the clock of St. Mary Woolnoth "kept the hours / With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine." This is the second of Hawksmoor's churches I pass, crammed into a tight space on a corner near the Bank of England and the ancient Roman Temple of Mithras, whose excavated foundations now pulse with mystic power in the basement of Bloomberg's European HQ.

A few minutes from St. Mary Woolnoth is Leadenhall Market, a quaint covered arcade tenanted by little food shops and pubs frequented by city workers. The market is a high Victorian confection of glass and iron, popular with filmmakers seeking a little heritage color. Pass through it and there's a sudden and extreme transition, a textbook instance of the Situationist "division of a city into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres." The Lloyd's building next door is the hub of a different kind of market, the global insurance trade. The vast tower is like something you'd find on a prog-rock album cover, a postmodern steel god veined with external pipes and ducts. Going from Leadenhall to Lloyd's feels like a particularly violent kind of time travel, as if you're an H. G. Wells character spat into the future, except that it's some airbrushed Seventies fantasy version of it. The Lloyd's building is strong evidence for Alan Moore's contention that the imaginary is the foundation of the physical world. The engineers of the City of London seem to have been engaged in a collective hallucination, bringing the capitalist future into being out of the ether. Currently, they are devoted to financing (and insuring, and calculating the risks of) giant data centers and rockets to Mars, eruptions out of dog-eared science-fiction paperbacks into the real world.

Outside Liverpool Street station, a pedestrian crossing marks the invisible border that separates all this money and power from the poverty of the East End. Turning off Bishopsgate, I am confronted—that would be the word—by the pale façade of Hawksmoor's Christ Church Spitalfields. Even on a sunny day it is chilling, a bone-colored mass topped by a cruelly sharp spire. It seems impossible that such a building could be allowed to fall derelict, but by the Sixties it came very close to being torn down. Supposedly built over a plague pit, Christ Church looms over the Ten Bells pub, where at least two of the Ripper's victims were said to have drank before they were murdered. This is the kind of connection that vibrates in the psychogeographical imagination, which is essentially a form of productive paranoia, an experience of intense interrelatedness, of being at the center of a story that doesn't really want to be a story, that would probably rather be a map or a diagram.

Growing up nearby, the painter Leon Kossoff, son of Russian Jewish immigrants, could not escape the presence of the church, alien and haughty, in a district that had become an almost entirely Jewish quarter. One of Kossoff's charcoal drawings of Christ Church hangs in the living room of the writer Iain Sinclair's house in Hackney, a gift from the artist. John Berger compared Kossoff to Beckett, and a sense of existential terror is present in the drawing, a kind of darkness that tugs at me as I drink my tea. Sinclair is probably the most adept living navigator of London's subterranean currents. His mind is a tangle of occult connections, a rat king of red thread. He is also the most robust link between the visionary London of Blake and Machen and the avant-garde mappings of the Situationists. In the early Seventies, he was writing poetry and working as a municipal gardener, cleaning and tending to the public spaces of the East End. He'd met Allen Ginsberg when he came to town in 1967, and remembers sitting on top of Primrose Hill with him, "aware of Blake's vision of Jerusalem being put down there. And being incredibly engrossed by the Post Office Tower—which had just been built—I suppose, as a sort of phallic symbol." Around the same time, he was in a secondhand bookshop "when a woman came out of a room and looked at me and said you should read this." Sinclair produces the book, and I laugh, because "this" is an early edition of E. O. Gordon's Prehistoric London: Its Mounds and Circles, first published in 1914. I have a reprint of the same book in my backpack. It tells stories about King Lud and Brutus the Trojan as if they are reliable historical facts. Inside, there is a "plan of the London mounds" with a triangle of dotted lines drawn between Parliament Hill, the Tower of London, and other significant places. Prehistoric London was described by one appalled reviewer as a "bewildering pot-pourri of Keltic traditions." Its sources include medieval chroniclers, eccentric antiquaries, and no doubt many denizens of the British Museum's Reading Room. It is utterly bogus, and central to Sinclair's strange refraction of the city.

As Sinclair picked up trash in East End graveyards, which at the time were in terrible disrepair, he became increasingly sensitive to Hawksmoor's architecture of terror and magnificence, and to the gruesome history of the area. The result was a book called Lud Heat: A Book of the Dead Hamlets, published in 1975, which fuses Gordon and Blake and Ginsberg and De Quincey and Jack the Ripper and Hawksmoor and hundreds more sources into an extraordinary metaphysical cacophony, a vision of a London traversed by lines of occult power. Quoting Yeats, Sinclair tells me, " 'The living can assist the imaginations of the dead.' The great things are unfinished, and our job is to attach ourselves to them and honor them and make them available and carry on." This is an oddly subversive notion of tradition, the past as secret society. Lud Heat found its way into the hands of Alan Moore, who was tinkering with inchoate ideas about murder. "That drops into my lap," he remembers, "and suddenly I can see a whole new way of focusing upon place. It knocks my entire prose style sideways for about the next ten or fifteen years." Without Gordon, there's no Lud Heat. Without Lud Heat, there's no From Hell. This is how the living assist the imaginations of the dead, infusing reality with fiction and altering the meaning of a city.

From Sinclair's house in Hackney I cut through Whitechapel to Wapping, past the site of Execution Dock, where the bodies of pirates were displayed on a gibbet just above the waterline, left to decay until the third high tide. The next Hawksmoor church I pass is St. George-in-the-East. During the Blitz, nightly waves of German bombers were sent to destroy the docks. The River Thames bends round in a horseshoe shape, easy for a bombardier to target. St. George-in-the-East was hit, its interior destroyed by fire. In 1964, a new church was built inside the old shell. I walk through a gateway, under yet another of Hawksmoor's stark towers, and find myself in a bright, bland space that is hosting a mother-and-baby group, a row of prams lined up against one wall. It is another sudden change of psychic atmosphere, all bustle and chatter and civic modernism.

A little farther down the old Ratcliffe Highway, once the scene of murders and press-gangings, is Limehouse. A giant anchor decorates the traffic island outside the old Sailors' Mission, which has now apparently been converted to apartments. According to a very dry report published in Internationale Situationniste, the Situationists' time in Limehouse was mostly taken up with formal political debates. The German faction split from the others, calling for an immediate mobilization of avant-garde artists rather than trusting the revolutionary capacities of the workers. Arguments went on late into the night.

Across from the Sailors' Mission is St. Anne's Limehouse, the fifth of the six Hawksmoor churches. St. Anne's served the old neighborhood of Pennyfields, London's first Chinatown. This was a place where other Asians also found a home, notably lascars from India and East Africa, and ayahs abandoned by their English employers after the long sea voyage. The barrackslike Strangers' Home for Asiatics, Africans, and South Sea Islanders once stood on West India Dock Road, providing assistance (and Christian preaching) to Asian people who had found themselves stranded in a country that considered them alien and frightening.

The dissident German contingent published their impressions of the Situationist conference in their own journal, SPUR, a much more fanciful tale than the serious French account. It includes a collaged picture of a turbaned Indian delegation that looks like it was cut out from a magazine. Was this a way of representing people they had met in Pennyfields or, as with Dali, Peggy Guggenheim, and a papal nuncio, just an entry in a list of attendees who were not actually there? Like the French, the Germans were very excited to be in Limehouse, "famous from crime novels." Somewhere in this vicinity is the opium-den headquarters of Sax Rohmer's fictional villain Fu-Manchu, "the yellow peril incarnate in one man." An ambulatory confection of racist stereotypes, Fu-Manchu appeared in a series of pulp novels and films in the first half of the twentieth century. A persistent internet factoid links him, unverifiably, to a mysterious stone pyramid in St. Anne's churchyard, supposedly the entrance to his lair. The pyramid is real, and genuinely mysterious. It is neither a grave marker nor a monument to an identifiable person or event. The best guess seems to be that it was one of a pair intended as ornamentation for the church, but was never mounted. It bears a very worn heraldic crest and the words the wisdom of solomon. Just that, no more. "The Wisdom of Solomon" is the title of a biblical text, but not one that is canonical for Protestants. In other words, it is an inscription that has no business in an English graveyard. An esoteric tradition takes Solomon's wisdom to be the Ars Goetia, ritual magic used to summon and bind demons.

Leaving St. Anne's, I follow a riverside path down the western side of the Isle of Dogs. After the Blitz, there was virtually nothing left of the old docks that had connected London's merchants to the Empire, or the foundries and yards where great ships had been launched. It languished for decades; redevelopment didn't really get going until the Eighties. The life of the modern Isle of Dogs is away from the water, in the commercial zone around Canary Wharf. It has been years since I walked this path; I remember the obelisklike tower of One Canada Square as the ruler of the skyline, a monument to the financialization that followed the deregulatory Big Bang of the Eighties. In Iain Sinclair's Docklands novel, Downriver, published in 1991, a few months before the building's grand opening, the tower is imagined as an occult center in a near-future London that lies under the control of "the Widow," a grotesque avatar of Margaret Thatcher. Nowadays it's hedged in by other tall buildings, many bearing corporate logos; these labels give the cluster an odd, simulated quality, as if I'm looking at the map rather than the territory.

A photograph of Blitz air-raid damage inflicted on the west side of Eastern Dock, northerly view from the south end, London, by John H. Avery & Co., September 8, 1940 © London Museum/PLA Collection/John Avery

During the Nineties, there was a revival of an organization called the London Psychogeographical Association (LPA), which had briefly existed in the Fifties. The new LPA was understandably obsessed with the Isle of Dogs and the rapid transformation it was undergoing. After the election of a neofascist politician named Derek Beackon to the local council in 1993, the LPA released a pamphlet with the headline nazi occultists seize omphalos. An omphalos (Greek for "navel") was defined as "the psychogeographical centre of any culture, myth structure or system of social dominance." "Beackon is a dedicated Nazi occultist," wrote the LPA. "British nationalism is a psychic elemental which drains energy from living people in order to maintain itself as a sickly caricature of life." The LPA claimed that Beackon and his cronies had taken control of this magical site and were using it to win political power. The new councillor was in fact an "adept of Enochic magic," a follower of none other than John Dee, who had come to the Isle of Dogs in 1593 to perform a magical ritual to found the British Empire. All those great ships, their holds full of human cargo, had been conjured up in an unremarkable spot in present-day Mudchute Park. Now, with its fantasies of mass deportation, the British National Party was tapping into a four-hundred-year-old darkness.

In the other London, truth is slippery. The "omphalos" in Mudchute Park, a little circle of cobbles visited sooner or later by most of London's psychogeographically inclined, can date to no earlier than 1868, when the dock was first developed. In Dee's day the site was featureless marshland. Alan Moore is frequently contacted by people who believe that the pentagram he drew across London in From Hell reveals some real ancient conspiracy. He lets them down gently. "If you've got a small enough map and a thick enough magic marker, any three points are in line. To me it's not so much about ley lines or earth energies or whatever, because I don't see how that works. What I do see is that if you link up three places on a map, then you are drawing a line between three points of information, points which perhaps were not connected before. You are considering those points of information in relationship to each other."

On a deserted stretch of walkway at the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs, I spot a man hanging over the water, clinging to the railing. I worry that he's about to jump off. Then I see that he's hanging on to the fence with one hand and wielding a trowel with the other. He is planting something in the narrow strip of earth in between the metal railing and the lip of the embankment. The sight is so strange, and he is so intent, that I hesitate to break his concentration. I hover, and when he finally looks up, I ask him what he's doing. They're succulents from his garden, he tells me. If they take, they'll grow all the way along. We are completely alone, in an eerie non-place of silent streets and residential blocks with maritime names. The only other people I've seen for some time were a group of young East African men taking pictures of themselves next to a sports car.

I am on the stairs that lead down to the Edwardian foot tunnel that runs under the river from the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs when I realize that the gardener is the one I've been looking for. Here is someone with a vision of another London, green and abundant, a vision he is dreaming into being. I should have talked to him properly, but I have missed my chance. My footsteps echo on the tunnel's white tile as I trudge along, knowing that it's too late to go back. At the southern end, I take an elevator and find myself in Greenwich, surrounded by tourists. After the sepulchral silence of the Isle of Dogs, it's a shock. I walk across a sort of piazza, under the tall masts of the clipper ship Cutty Sark. The last of the Hawksmoor churches is just around the corner. This is a wealthy neighborhood, bustling with shoppers. I look at St. Alfege, which is trim and well-kept, though just as stark and bony as its sisters. In the graveyard, I sit down on a bench, then get up to help a couple chase an excitable terrier, which they've foolishly let off the leash.

In this story, I should continue my walk up the hill through Greenwich Park to the prime meridian, making the magical link to the British Museum. I should describe how a circuit is completed; how a metaphysical light switches on in my head. But something has shifted, some energy has drained away. At times on my walk, I have felt like a ghost, existing more in the past, or an imaginary past, than the present. High on a wall on Fournier Street, beside the arrogant spire of Christ Church Spitalfields, I had seen an eighteenth-century sundial bearing the inscription umbra sumus: "We are shadow." Yes, I thought as I walked underneath it. That is all I am. I have passed an unusual number of street-corner memorials, laminated sheets of paper attached to railings, surrounded by wilted flowers and candles; photos of smiling young men who met untimely deaths in nondescript spots, deaths that the city will forget as soon as the memorials are taken down. Then I met the magus planting his hanging garden by the river, but I wasn't sharp enough, quick enough, to catch his message. Now the sense of being in touch with life and death has gone, and I can feel normality falling over me like a blanket.

I remember something Alan Moore told me: "It is so important to reenchant these places that we live in, to actually give back the energies that have been bled out of them. An empowered landscape creates empowered people, and the reverse is also true. A disempowered landscape, stripped of its history, stripped of its meaning, will produce people who are stripped of their history, of their meaning. So yes, if magic is anything, it has to be political."

Though I have fallen away from my intention, failed to complete my quest, I have convinced myself that the other London is still possible to find, and it is important to keep looking for it. But for now I am standing at the bus stop, waiting for the number fifty-seven. It begins to rain.

From the

From the

Subscribe or log in to access this PDF:

From the ArchiveTimeless stories from our 175-year archive handpicked to speak to the news of the day.

Email address Related Another London

Excavating the disenchanted city

by Hari Kunzru

Another London

Excavating the disenchanted city

by Hari Kunzru

The Sanctuarium

The Philippines reckons with its war on drugs

by Sean Williams

Hari Kunzru

The Sanctuarium

The Philippines reckons with its war on drugs

by Sean Williams

Hari Kunzru

's latest novel is Blue Ruin. He teaches in the creative writing program at New York University. This essay is part of a series supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

Tags British Empire David Granick Derek Jarman dérive Jamie Reid King Mob London Mass media Psychogeography Sex Pistols T.S. Eliot Thames River The Situationists Thomas De Quincey William Blake William Hogarth William Lake Price More from Hari Kunzru Lo-fi Beats for Work or Study

I've written in many places, some wonderful, others makeshift or uncomfortable. I've written on trains and in hotel rooms, at ergonomically perfect desks and on laptops balanced on my knees.…

Lo-fi Beats for Work or Study

I've written in many places, some wonderful, others makeshift or uncomfortable. I've written on trains and in hotel rooms, at ergonomically perfect desks and on laptops balanced on my knees.…

Above Politics

For all those involved in the publication and dissemination of ideas, freedom of expression is the foundation on which our work depends. Like many writers, I have campaigned to defend…

Above Politics

For all those involved in the publication and dissemination of ideas, freedom of expression is the foundation on which our work depends. Like many writers, I have campaigned to defend…

Be Here Now

On March 14, 2010, the artist Marina Abramovic sat down at a small table in the center of a gallery in the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. Visitors were invited…

Thanks to

Be Here Now

On March 14, 2010, the artist Marina Abramovic sat down at a small table in the center of a gallery in the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. Visitors were invited…

Thanks to

- Current Issue Advertising Permissions and Reprints Internships Customer Care

- Contact Careers Classifieds Help

- Archive Submissions Find a Newsstand

- About Media Store Terms of Service Privacy Policy

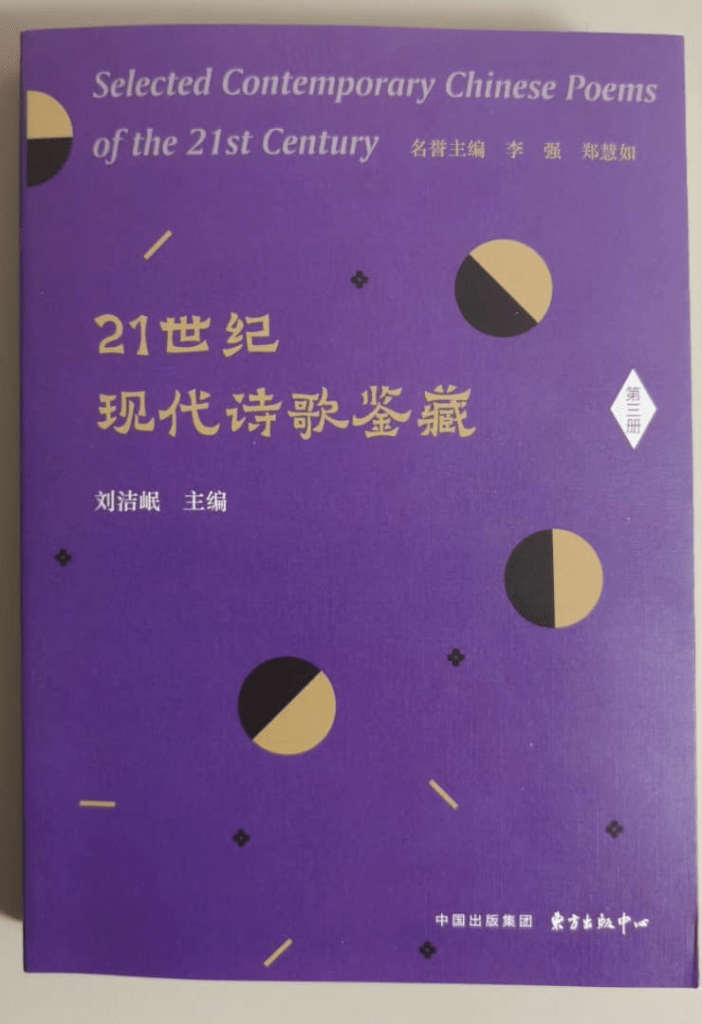

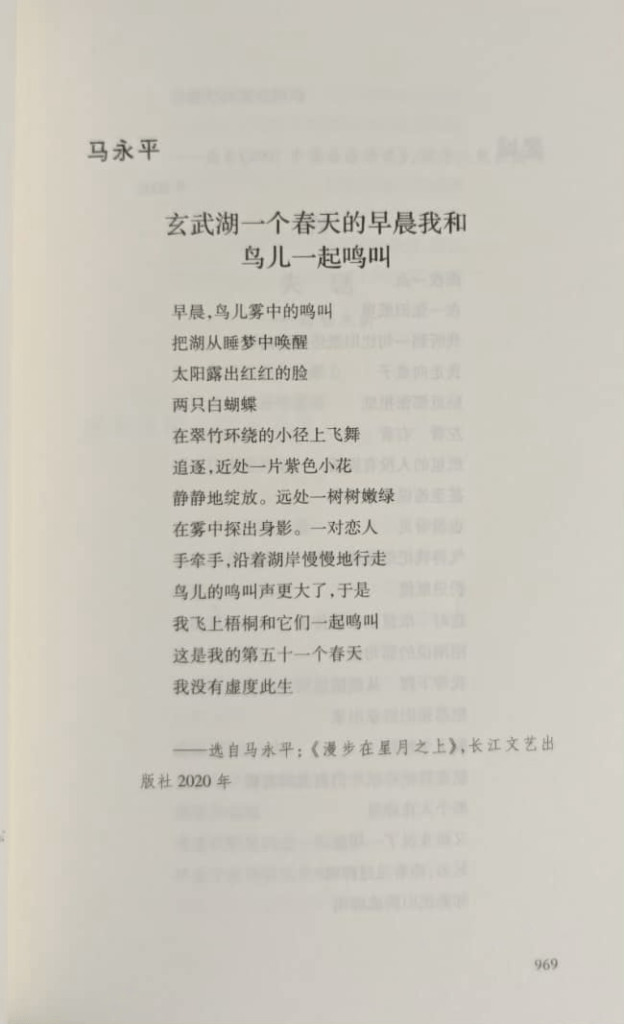

Ma Yongbo 马永波, Reflecting on Dialectic Translational Poetics: the conversations of Bear and Kitten.

Reflections on Reading Helen's Many Poems for Me

观海伦诸多赠诗有感

Must you insist on stabbing

my body, which is already leaking everywhere

with your Western fountain pen

until it becomes a sieve of holes?

Yet I only sketch you with a soft brush