29-Jan-26

More people came to Carol's funeral than there were seats in the crematorium chapel: our families, her friends and mine, some of whom had travelled a long way. The funeral directors, P B Wright and Sons, took care of the arrangements kindly and professionally. Catriona Miller, the humanist celebrant, conducted the service and delivered a warm and accurate tribute to Carol. I spoke about Carol's life with me, and Michael spoke for himself and Sharon about Carol as a mother. Two hymns were sung that had also been sung at our wedding. The closing music was a song Carol had played countless times: 'Stars' by Simply Red.

The Order of Service booklet featured a fine recent photograph of Carol by Michael, and some of Carol's own photographs of Gourock's sunset skies.

The collection was for two charities that Carol had actively supported: the RNLI, and Medical Aid for Palestinians. It raised £1138.50, which yesterday I rounded up to £1200 and divided evenly into two donations in her memory.

Many, many thanks to all who attended, and to all who contributed so generously, at the collection and online. Thanks also for the many messages and cards of sympathy, for which I and all the family are deeply grateful.

28-Aug-24

Carol Ann MacLeod, 11 February 1952 to 16 August 2024

Carol, my beloved wife whom I met in 1979 and married in 1981, died on Friday 16 August.

Carol, my beloved wife whom I met in 1979 and married in 1981, died on Friday 16 August.

She was the centre of my world, and she's gone.

There will be a funeral service at Greenock Crematorium, on Monday 2 September, at 2 pm, to which all family and friends are invited. Family flowers only please. There will be a retiral collection in aid of Carol's favourite charities. #

05-Aug-24

My Glasgow Worldcon Schedule

As some of you may know, I'm a Guest of Honour at the Glasgow Worldcon. I haven't said enough about that here, I know. I'm well chuffed about it, needless to say. Here are time/places where you can be sure to find me.

Autographing: Ken MacLeod, Thursday 8 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Autographs)

Opening Ceremony, Thursday 8 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Morrow's Isle - Opera, Thursday 8 August 2024, 20:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Iain Banks: Between Genre and the Mainstream, Friday 9 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Alsh 1

Luna Press Book Launch Party, Friday 9 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Argyll 2

Guest of Honour Interview: Ken MacLeod, Friday 9 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Lomond Auditorium

Table Talk: Ken MacLeod, Saturday 10 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Table Talks)

The Making of Morrow's Isle - An Opera, Saturday 10 August 2024, 14:30 GMT+1, Argyll 2

NewCon Press Book Launch, Saturday 10 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Argyll 3

The Politics of Modern Scottish SF, Saturday 10 August 2024, 20:30 GMT+1, Castle 1

Reading: Ken MacLeod, Sunday 11 August 2024, 10:00 GMT+1, Castle 2

Autographing: Ken MacLeod, Sunday 11 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Autographs)

An Ambiguous Utopia: 50 Years of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed, Sunday 11 August 2024, 14:30 GMT+1, Meeting Academy M1

2024 Hugo Awards Ceremony, Sunday 11 August 2024, 20:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Stroll with the Stars - Monday, Festival Park, Monday 12 August 2024, 09:00 GMT+1, Outside Crowne Plaza

Writing Future Scotland, Monday 12 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Lomond Auditorium

#

03-Nov-23

Chengdu Worldcon: Meet the Future [ 03-Nov-23 10:06pm ]

Chengdu Worldcon: Meet the Future [ 03-Nov-23 10:06pm ]

This historic Worldcon has already been very well covered by others, e.g. Nicholas Whyte and Jeremy Szal. For lots of coverage of events, guests and so on, see the con's Facebook page.

But I've been back over a week, and here's my overdue account.

Last month I spent far too few days in China, at the Chengdu Worldcon, to which I was invited as an international guest. My travel, and accommodation for me and my wife, were covered by the Committee of the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention, for which much thanks.

We had a wonderful time. The convention was a smashing success and easily the biggest, and most publicly celebrated, Worldcon ever.

We arrived at Chengdu airport in the early evening of Wednesday 18 November and quickly met volunteers at a stall near the exit, from which were immediately hurried to a minibus that took us to the Sheraton Pidu. Along the way we saw advertisements for the Chengdu Worldcon lining the highways, and the robot panda mascot at numerous intersections. We met the volunteer who was looking after us, Zoe, who was unfailingly sweet and helpful throughout. Our luggage was whisked inside and we were back on a bus for a short drive to the venue.

This was the elegant and futuristic newly built Chengdu Science and Science Fiction Museum, across a lake in the park from the hotel. We took our seats just in time for the start of the opening ceremony.

This was the elegant and futuristic newly built Chengdu Science and Science Fiction Museum, across a lake in the park from the hotel. We took our seats just in time for the start of the opening ceremony.

This combined a traditional Worldcon opening ceremony...

...with a spectacular show, including song and dance, giant video projections, and culminated in a drone display outside the huge semi-circular window of astronomical and sci-fi images whose high point was an outline rendering of a spinning black hole (which unfortunately I didn't catch, so you'll have to make do with Saturn).

...with a spectacular show, including song and dance, giant video projections, and culminated in a drone display outside the huge semi-circular window of astronomical and sci-fi images whose high point was an outline rendering of a spinning black hole (which unfortunately I didn't catch, so you'll have to make do with Saturn).

The other ceremonies - the Galaxy Awards, the opening of the Chengdu International Science Fiction convention, the Hugo Awards, the Hugo after-party, and the closing ceremony - were likewise spectacular: a primary school choir sang in one of these, an entire symphony orchestra took the stage in another, and so on.

They were MC'd by professional television presenters.

They were MC'd by professional television presenters.

The venue was as impressive inside as outside.

The venue was as impressive inside as outside.

I took part in a couple of panels, one on Science Fiction and Future Science and one on cyberpunk, and was interviewed on video by an Italian documentary company and on voice recording for the Huawei news website. For two mornings I put in an hour or two at the Glasgow Worldcon stand. Never in my life have I been asked for so many autographs, or to pose with so many people for photographs. Nicholas Whyte, also at the stall, had the same experience, and others did too. Hardly any of the people whose notebooks and souvenirs we signed, or who stood beside us to have their photo taken, could have known who we were: that were overseas visitors with something to do with science fiction was enough. Among the few who did know us were some students from the Fishing Fortress College of Science Fiction in Chongqing.

Our enthusiastic reception was nothing to that of Cixin Liu, author of the Three-Body trilogy and the story filmed as The Wandering Earth. His signing queue was like those I've seen for Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Science fiction in China is taken very seriously and sincerely by its fans.

I took part in a couple of panels, one on Science Fiction and Future Science and one on cyberpunk, and was interviewed on video by an Italian documentary company and on voice recording for the Huawei news website. For two mornings I put in an hour or two at the Glasgow Worldcon stand. Never in my life have I been asked for so many autographs, or to pose with so many people for photographs. Nicholas Whyte, also at the stall, had the same experience, and others did too. Hardly any of the people whose notebooks and souvenirs we signed, or who stood beside us to have their photo taken, could have known who we were: that were overseas visitors with something to do with science fiction was enough. Among the few who did know us were some students from the Fishing Fortress College of Science Fiction in Chongqing.

Our enthusiastic reception was nothing to that of Cixin Liu, author of the Three-Body trilogy and the story filmed as The Wandering Earth. His signing queue was like those I've seen for Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Science fiction in China is taken very seriously and sincerely by its fans.

Thousands upon thousands of people passed through the venue, including many primary-school classes there for the day. Lots of young people, and lots of families. They weren't just there for the toys and for the impressive tech exhibition hall.

The bookstall just across from the Glasgow Worldcon stall had a fast-moving queue of book-laden customers all the time. Many panels were standing room only, with people crowding the doorway leaning in and recording on their phones.

The bookstall just across from the Glasgow Worldcon stall had a fast-moving queue of book-laden customers all the time. Many panels were standing room only, with people crowding the doorway leaning in and recording on their phones.

There were hundreds of volunteers, some minding the international guests, others helping visitors to the venue, acting as guides in exhibitions, or adding some elegance to the ceremonies.

Some even worked on security (the hotel and the venue had almost airport-level security throughout the convention). Most seemed to be from language schools, and eager to practice their English.

Some even worked on security (the hotel and the venue had almost airport-level security throughout the convention). Most seemed to be from language schools, and eager to practice their English.

Our good friend Fan Zhang, who looked after us so well in Beijing in 2019, now has an important post at the Fishing Fortress college of Science Fiction. He took us out to dinner with two of his staff, and had some interesting proposals for next year, which I'm seriously considering.

We had one side trip organised by the convention for guests: a visit to Chengdu's famous panda research centre, truly unforgettable.

Alongside the hotel was an exhibition of 'Intangible Cultural Heritage', traditional arts and crafts: Shu embroidery not just displayed but demonstrated, traditional music and singing, silver filigree, a tea ceremony, cut-paper pictures, and melted-sugar drawings made before our eyes and handed to us on a stick to eat. It all made for an interesting and uplifting hour.

Alongside the hotel was an exhibition of 'Intangible Cultural Heritage', traditional arts and crafts: Shu embroidery not just displayed but demonstrated, traditional music and singing, silver filigree, a tea ceremony, cut-paper pictures, and melted-sugar drawings made before our eyes and handed to us on a stick to eat. It all made for an interesting and uplifting hour.

On our final day, Monday 23 October, Carol and I went on our own to the Wuhou Shrine, a historic site and major tourist destination set in a great park which opens to some old streets, now lined with gift shops and street food stalls.

And on Tuesday we began the long journey home. We had met old friends and made new ones, and it was a pang to leave.

We owe thanks to many people - the organisers and volunteers, especially Zoe, and a special thanks to the indefatigable Sara Chen. 20-Apr-23

20-Apr-23

Moniack Mhor is Scotland's creative writing centre, located in a spectacular landscape in Inverness-shire. I've taught there before, with Mike Cobley, and it was great. But a residential week or long weekend isn't for everyone, which is why Moniack Mhor offers 'Moniack in a Month': courses held over Zoom, with one evening workshop a week for four weeks, plus one-to-one tutorial sessions and guest events.

Moniack Mhor is Scotland's creative writing centre, located in a spectacular landscape in Inverness-shire. I've taught there before, with Mike Cobley, and it was great. But a residential week or long weekend isn't for everyone, which is why Moniack Mhor offers 'Moniack in a Month': courses held over Zoom, with one evening workshop a week for four weeks, plus one-to-one tutorial sessions and guest events.

I'm delighted to say that bookings are now available for an online course on writing science fiction which I'll be teaching this September. Details are here. The wonderful Justina Robson has kindly agreed to be our Guest Reader.

27-Mar-23

Interview [ 22-Jan-23 2:10pm ]

Interview [ 22-Jan-23 2:10pm ]

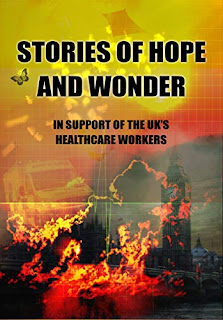

The idea of a society of entirely voluntary arrangements has its charms, but we don't live in one and are not likely to for quite some time. Until that happy day, public services should be funded out of taxation, rather than having to scrounge off the generosity of the public. In emergencies, however, we should pitch in. That's how I square my conscience with making donations, anyway. And if the inadequate supply of PPE to healthcare workers isn't an emergency, I don't know what is.

The idea of a society of entirely voluntary arrangements has its charms, but we don't live in one and are not likely to for quite some time. Until that happy day, public services should be funded out of taxation, rather than having to scrounge off the generosity of the public. In emergencies, however, we should pitch in. That's how I square my conscience with making donations, anyway. And if the inadequate supply of PPE to healthcare workers isn't an emergency, I don't know what is.

So I was happy to contribute a story to an anthology of SF, fantasy and horror conceived and edited by Ian Whates at NewCon Press, and compiled and published with breathtaking speed. At a quarter of a million words from some of the leading names in the field, a paperback version would be an epoch-making brick that cost a significant chunk of cash. Electronic and weightless, Stories of Hope and Wonder is a steal at £5.99 / $7.99. Every penny of the proceeds goes straight to providing PPE and other support to UK healthcare workers. A significant amount, I understand, has already been raised and donated. More is needed.

They can't wait. Buy it now.

13-Apr-20

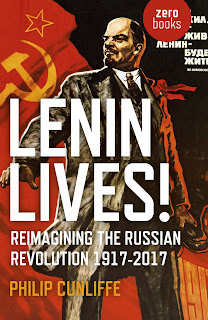

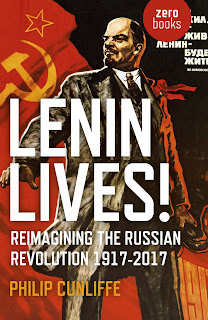

Lenin Lives!

Lenin Lives!

Philip Cunliffe

Zero Books, 2016

It can be disconcerting to read a book that upends your way of looking at the world. It's even more disconcerting when that book claims your own work as part of its inspiration. About which, more later.

The book's title and Soviet-kitsch cover are deeply ironic: baiting for some, and bait for others. In the alternate-history world Cunliffe imagines, Lenin is almost forgotten, because he succeeded. (It's tempting to add 'beyond his wildest dreams' but success beyond Lenin's wildest dreams would have meant spreading the revolution to the canal-builders of Mars.)

For what Lenin and the Bolsheviks set out to do in 1917 was to detonate an international, indeed global, revolution. This was an immediate perspective, where revolutionary romanticism meant staking all on the world revolution breaking out next week, while sober realism meant bearing in mind that it might be delayed for a few more months. In fact even the realists were too optimistic: it was delayed for a whole year. In November 1918 the red flags went up over the naval base at Kiel, and flew over all Germany within days. And then...

Well, everybody knows.

But what if the grip of German Social Democratic reformism had been that little bit shakier, and the revolutionary Left that little bit better organised and luckier? Cunliffe speculates on what sort of world might now exist, and how it might have come about, if the revolution that began in Russia had not only spread - as it did - but won, as it didn't.

In this missed turn of history, a decade or so of wars and civil wars see the capitalist core countries having gone socialist. The major independent underdeveloped countries have gone democratic, and the former colonial holdings have mostly opted to remain in loose voluntary federations that have replaced the empires. It's not all plain sailing but the resulting democratic workers' states of Europe and America are much less repressive than Bolshevik, let alone Stalinist, Russia was in our world. Planning emerges from increasing coordination (as indeed it did under the New Economic Policy) rather central imposition. Industrialisation proceeds at a brisk but measured, rather than a frantic, pace. Art, science, culture and personal freedom flourish. This is a world with no fascism or Stalinism, no Depression and no Second World War. Whether or not the reader finds it feasible or desirable, it's attractively and vigorously portrayed.

Cunliffe's alternate history has no decisive moment (no Jonbar Point, to use the science-fictional term) that I can see. Instead, the international revolutionary working-class movement (which, as Cunliffe usefully and repeatedly reminds us) actually did exist at the time is imagined as having been just a little bit stronger in arm and clearer in mind than it was in our world. It's by no means an unrealistic speculation. Even in our world, it was a close-run thing. So close, in fact, that stamping out every last smouldering ember of world revolution took tens of years and tens of millions of lives. But its suppression is now, at last, complete.

E. H. Carr, in an article or interview for New Left Review, remarked that all of Marx's predictions had come true, except for the proletarian revolution. Cunliffe's view is gloomier: he thinks that they all came true, including the revolution. It really happened, in 1917-1923, and the revolutionaries bungled it.

When most readers of the Communist Manifesto encounter the passage about how throughout history classes have waged 'an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes' the example that springs to mind is the Fall of the Roman Empire to the barbarians. What Marx and Engels were really alluding to, Cunliffe argues, was subtly different: the Fall of the Republic, rather than the Fall of the Empire. It was the class struggles of patrician and plebeian in the Roman Republic that ended in mutual ruination, and stymied any chance of further progress centuries before the Empire fell.

If readers of the Manifesto are socialists, the common ruin they envisage for bourgeoisie and proletariat is a nuclear war or environmental catastrophe. No such luck, Cunliffe tells us: the common ruin has already happened. The class struggle between bourgeoisie and proletariat is over. The good guys lost. Get over it.

But the non-socialist reader can take no comfort. The suppression of communism, Cunliffe claims, undermined capitalism, sapping its economic dynamism and political stability. With no competing model - however unattractive in many respects - to keep it on its toes, capitalism becomes a couch potato. With no union militancy and shop-floor organisation to contend with, capitalists have less incentive to innovate and rationalise. With no need to integrate the working class in the affairs of state, mass political participation and engagement have been texted their redundancy notices.

The result, however, is that the elites and the rest of the population are more mutually alienated than they ever were in the class struggle. To the political class and state authorities, the ideas and attitudes of the underlying multitude are as a dark continent, viewed with alarm and suspicion, alternately patronised and deplored. Unmoored from the clash of material interests, politics drifts into a Sargasso Sea of slowly, pointlessly, endlessly swirling debris. Debate degenerates into a grandstanding narcissism of small differences around an elite consensus dedicated solely to keeping the show on the road. Political apathy and populist eruptions are its morbid symptoms. The ruin was mutual, and the ruins are where we must henceforth live.

This exhausted order could in principle totter along indefinitely, were it not for the instabilities, internal and external, that result. The political and moral authority of the state quietly unravels, even as its hard power and reach expand. As Britain's riots of 2011 starkly exposed, social order itself can dissipate overnight. And the quest for moral authority at home is transmitted all too easily into rash adventuring abroad, in the name of democratic and liberal values. To explain, say, the Iraq war as motivated by strategic or economic concerns, a 'war for oil', as leftists are wont to do, is misconceived. There's no underlying interest to expose: the war's liberal-democratic rationalisation really is what it's all about. As Tony Blair said: 'It's worse than you think. I believe in it.'

Readers of my own novels, particularly the Fall Revolution books and some of the more recent ones such as Intrusion and Descent, may find some of the themes outlined above familiar. In the early 1990s when I started writing my first novel, I was convinced that the Left had suffered a whopping, world-historic defeat with the fall of the Soviet bloc regardless of how critical or even hostile they had been to it. However, I did expect that this defeat would in time be overcome.

Whatever else it does, Lenin Lives! answers a question that has baffled better minds than mine: how on earth did a splinter of the far left mutate into a cadre of contrarian libertarian Brexiters? Two lines of explanation are often explored. The first is that they remain revolutionary communists under deep cover, engaged in some nefarious long-term scheme. The second is that they have been themselves subverted, suborned by the corporations from which they receive funding. I could go into the various reasons why both are wide of the mark, but I've already gone on long enough. By now you can figure it out for yourself:

It's worse than you think. They really believe in it.

The Early Days of a Better Nation [ 1-Jan-26 2:19pm ]

Looking back, looking ahead [ 01-Jan-26 2:19pm ]

Happy New Year!

For me 2025 has been mostly a year of spending time with family and with getting on with stuff, and with letting some stuff pile up while working on my next novel, provisionally titled Empire Time. Progress has been slower than I'd hoped, but my agent and my editor have been very understanding. It's now close to the end of the first draft, but I have a major plot thread to untangle and tie off, so that's my writing priority for now (immediately after sorting out some of the other stuff I had let pile up, mostly urgent admin and, well, literal stuff piling up).

Things I didn't write about but probably should have: I had a good time at Reconnect and at the first Pictcon, a one-day convention which was successful in every way and is scheduled for a return this year.

Some of the literal stuff piling up has been recent issues of New Scientist which I've yet to read, but the good people who work there weren't to know that when they asked me to be interviewed for their Book Club about Iain M. Banks and his novel The Player of Games, which I re-read with much enjoyment and talked about with enthusiasm, as you can see. Alison Flood was an excellent interviewer, and made it a relaxed conversation. My office as you see it in the video is after I had tidied it.

Looking ahead: I'm reading and being interviewed as part of the Beacon Book Festival in Greenock in February.

For local writers and readers I'm giving a talk on writing science fiction to the Greenock Writers' Club on 4 March. For members only, but new members are always welcome!

Looking back and ahead: in late 2024 my brother James came to Greenock to visit me and to give a talk, illustrated with slides and statistics, which went down very well with a large local audience. The topic of religious imagery on Scottish war memorials may seem narrow, even niche, but the way Professor James MacLeod handles it, I can assure you it's not. Now, everyone in the world who wants to and can spare £5 has a chance to see it online, live on 15 January. Tickets here.

14-Apr-25

For me 2025 has been mostly a year of spending time with family and with getting on with stuff, and with letting some stuff pile up while working on my next novel, provisionally titled Empire Time. Progress has been slower than I'd hoped, but my agent and my editor have been very understanding. It's now close to the end of the first draft, but I have a major plot thread to untangle and tie off, so that's my writing priority for now (immediately after sorting out some of the other stuff I had let pile up, mostly urgent admin and, well, literal stuff piling up).

Things I didn't write about but probably should have: I had a good time at Reconnect and at the first Pictcon, a one-day convention which was successful in every way and is scheduled for a return this year.

Some of the literal stuff piling up has been recent issues of New Scientist which I've yet to read, but the good people who work there weren't to know that when they asked me to be interviewed for their Book Club about Iain M. Banks and his novel The Player of Games, which I re-read with much enjoyment and talked about with enthusiasm, as you can see. Alison Flood was an excellent interviewer, and made it a relaxed conversation. My office as you see it in the video is after I had tidied it.

Looking ahead: I'm reading and being interviewed as part of the Beacon Book Festival in Greenock in February.

For local writers and readers I'm giving a talk on writing science fiction to the Greenock Writers' Club on 4 March. For members only, but new members are always welcome!

Looking back and ahead: in late 2024 my brother James came to Greenock to visit me and to give a talk, illustrated with slides and statistics, which went down very well with a large local audience. The topic of religious imagery on Scottish war memorials may seem narrow, even niche, but the way Professor James MacLeod handles it, I can assure you it's not. Now, everyone in the world who wants to and can spare £5 has a chance to see it online, live on 15 January. Tickets here.

Fame at last [ 14-Apr-25 5:43pm ]

It seems I've become a local celebrity, because I was asked to officially open the new Sue Ryder charity shop in Port Glasgow on Friday. The staff, management and volunteers were most welcoming, and cutting a ribbon is much easier than it looks. (George Munro's pic, in the Greenock Telegraph article linked above, caught the exact moment.) The charity's photographer Andy Catlin was there to record the occasion and he offered me these pictures for my blog. The shop is large, well-stocked, and right in the main shopping centre, so it should do well.

As the press release put it: 'Every item you purchase, every donation you make, goes towards helping Sue Ryder support people through the most difficult time of their lives. Whether that's dealing with the grief of losing a loved one or a terminal illness, your contribution can directly help fund the care and support the charity offers.' A worthy cause which I'm more than happy to promote.

I bought a copy of Longitude by Dava Sobel, a book I'd always meant to read, and did over the next couple of days. Highly recommended, and duly passed on to another keen reader.-7936.jpg)

-7969.jpg)

-8115.jpg)

10-Apr-25

As the press release put it: 'Every item you purchase, every donation you make, goes towards helping Sue Ryder support people through the most difficult time of their lives. Whether that's dealing with the grief of losing a loved one or a terminal illness, your contribution can directly help fund the care and support the charity offers.' A worthy cause which I'm more than happy to promote.

I bought a copy of Longitude by Dava Sobel, a book I'd always meant to read, and did over the next couple of days. Highly recommended, and duly passed on to another keen reader.

-7936.jpg)

-7969.jpg)

-8115.jpg)

Stuff I'm doing [ 10-Apr-25 5:45pm ]

I'm working on my next novel, provisionally titled Empire Time. It's a space opera. That's all I'm saying about it for now.

Apart from that…

Usually, I don't read science fiction while I'm writing it, and especially not in the sub-genre I'm writing in. But sometimes you have to make an exception. I read or re-read a stack of science fiction recently, to compile lists for the Scottish Book Trust's Book Subscription: Science Fiction. There's a choice of three or six months, with a book a month, attractively packaged and with a note from me saying why it's worth reading. If you're new to science fiction, or just starting out in the genre, you should find it a good overview. The selections cover a wide range: long books and short, classic and recent, from space opera to alternate history to near future.

I'm very much looking forward to going to Reconnect, the Belfast Eastercon. (Eastercon is the annual UK science fiction convention.) Despite my late decision to go, I'm on the programme, for which much thanks. With over 800 attending members, it looks like this Eastercon will be a good one.

21-Feb-25

Apart from that…

Usually, I don't read science fiction while I'm writing it, and especially not in the sub-genre I'm writing in. But sometimes you have to make an exception. I read or re-read a stack of science fiction recently, to compile lists for the Scottish Book Trust's Book Subscription: Science Fiction. There's a choice of three or six months, with a book a month, attractively packaged and with a note from me saying why it's worth reading. If you're new to science fiction, or just starting out in the genre, you should find it a good overview. The selections cover a wide range: long books and short, classic and recent, from space opera to alternate history to near future.

I'm very much looking forward to going to Reconnect, the Belfast Eastercon. (Eastercon is the annual UK science fiction convention.) Despite my late decision to go, I'm on the programme, for which much thanks. With over 800 attending members, it looks like this Eastercon will be a good one.

Wish you were here [ 21-Feb-25 9:49pm ]

It's been six months. Raw grief fades, and often flares. I miss Carol more than ever. Absence doesn't go away.

We used to take photos of our shadows: shadow selfies. 'Smile!' the one taking the photo would say, and we'd laugh.

This post is here to fill space. Skip it if you like. After it the blog will get back to its usual intermittent rambling about trivia, politics, science fiction, science, and materialism. I don't want to click on it to check something, and be thrown back to the funeral. I have that photo of Carol framed in my living-room. This post is here to be a buffer, a shock absorber.

I've been getting on with things. I have family, and I have friends, and they've helped. There's a book to write, which is coming together like a shape emerging from fog. There have been other projects. I had engagements, which I left too late to break. The first was a few days after Carol's funeral, at the Seahorse Bookstore in Ardrossan. It was good to get out, and the owners and staff were lovely. One of my sisters and her husband, who live locally, came along. It was a good event, on a day of long bus rides. The worst pang was the bus back from Largs to Gourock, a short journey I'd often made with Carol.

Back in January, I'd got an invitation to the Gothenburg Book Fair. Carol and I had been to Sweden before, in August 2003. That was when we first met Alastair Reynolds and his wife Josette, and we'd been friends ever since. We'd explored Uppsala and Stockholm and its archipelago, met some of the SF-Bokhandeln people, and had a great time. And I'd been back since, this time on my own and to Gothenburg, in what was for me a busy and fraught year, 2015, for FSCONS.

So of course I asked Carol if she wanted to come with me, and of course she did. We paid her fare, and the Book Fair took care of everything else. They even put us up in the hotel for an extra couple of nights.

The flight was at 06:10 on Wednesday 25 September. I considered booking a taxi for 03:00, and decided to get a train and bus to the airport on Tuesday evening. It felt very strange to be locking the door for a trip and not having Carol going down the stairs ahead of me. I walked along to Cleats, where I had a half pint with the local SF crew, and on to the station. At Glasgow Airport I found a corner seat in Greggs, and read and dozed until it was time to join the queue. Apart from a two-hour delay in Amsterdam, the fight was uneventful. I was met by a taxi at the airport, and taken to Gothia Towers Hotel, adjacent to the venue, an enormous exhibition centre.

Erik Eje Almqvist met me in the lobby, treated me to a beer and lunch in the restaurant, and got me my guest badge and packet. The main theme of the Book Fair was Sápmi, the homeland of the Sámi people. A second theme was space. Quite a number of people in the corridors wore brightly coloured and embroidered Sámi clothing.

The room was splendid and had a spectacular view.

I had a nap, freshened up, and took the lift to the opening party. There the view was even more spectacular and even more people wore Sámi clothing. Everyone was speaking Swedish, but Erik spotted me and steered me into a conversation with a Lutheran clergywoman, so I had someone to chat with over my first glass. Later I had a couple of beers with Glenn Petersen of SF-Bokhandeln. A band played something that was meant to evoke space or cyberpunk, and Johan Stanberg McGuinne performed a joik. I was struck by some resemblances to Gaelic singing and the cadences of Highland heightened speech in preaching and poetry. Afterwards, I raised this rather tentatively with Johan, who surprised me by agreeing. Of Gaelic and Sámi heritage himself, Johan pointed out that these two cultures were unlikely to have influenced each other. An agreeable puzzle.

Thursday was one of my extra days, so after breakfast I picked up a Gothenburg tourist booklet in the hotel lobby and set off on the kind of local wander that Carol and I would have done. This included an amphibious bus tour, a late lunch of a massively filled sandwich at the food market, and a stroll through the botanic garden, which ended in me sitting on a bench and being acutely aware that Carol wasn't beside me.

I walked back to the hotel just as the rain was starting, and had a look around the book fair, which was spread across four large and crowded halls.

The following days, these halls were packed. Every day, tens of thousands of people turned up. Every publisher and, it seemed, every reader in Sweden was there. I may write more about it sometime. I had a good time, I met new people, and I met up with Alastair Reynolds, Paul McAuley and Peter Hamilton, and we had breakfasts and beers. On the last day Glenn Petersen and his wife Ylva took us and their colleagues out for dinner at a Michelin starred restaurant. I asked Ylva if she could recommend somewhere to go on Sunday, the last of the free days we'd booked, and she suggested Marstrand Island. What I wanted to do, again, was take the sort of sight-seeing trip that Carol and I would have taken if she'd been there. This sounded exactly right.

It was. The bus rides were long, but the scenery was amazing, and every bus was on time. Marstrand Island is a five-minute ferry crossing from the terminus. Its main feature is a naval fortress, which unlike many such around the world has seen action.

Going around it was a pang. In 2023, Carol and I had explored a much larger naval fortress, at Pula in Croatia. Much larger, yes, but the layout has its own logic, and every corner had a sharp memory rising unbidden around it.

The views were great. Carol would have enjoyed it, if she'd been there.

11-Sep-24

We used to take photos of our shadows: shadow selfies. 'Smile!' the one taking the photo would say, and we'd laugh.

This post is here to fill space. Skip it if you like. After it the blog will get back to its usual intermittent rambling about trivia, politics, science fiction, science, and materialism. I don't want to click on it to check something, and be thrown back to the funeral. I have that photo of Carol framed in my living-room. This post is here to be a buffer, a shock absorber.

I've been getting on with things. I have family, and I have friends, and they've helped. There's a book to write, which is coming together like a shape emerging from fog. There have been other projects. I had engagements, which I left too late to break. The first was a few days after Carol's funeral, at the Seahorse Bookstore in Ardrossan. It was good to get out, and the owners and staff were lovely. One of my sisters and her husband, who live locally, came along. It was a good event, on a day of long bus rides. The worst pang was the bus back from Largs to Gourock, a short journey I'd often made with Carol.

Back in January, I'd got an invitation to the Gothenburg Book Fair. Carol and I had been to Sweden before, in August 2003. That was when we first met Alastair Reynolds and his wife Josette, and we'd been friends ever since. We'd explored Uppsala and Stockholm and its archipelago, met some of the SF-Bokhandeln people, and had a great time. And I'd been back since, this time on my own and to Gothenburg, in what was for me a busy and fraught year, 2015, for FSCONS.

So of course I asked Carol if she wanted to come with me, and of course she did. We paid her fare, and the Book Fair took care of everything else. They even put us up in the hotel for an extra couple of nights.

The flight was at 06:10 on Wednesday 25 September. I considered booking a taxi for 03:00, and decided to get a train and bus to the airport on Tuesday evening. It felt very strange to be locking the door for a trip and not having Carol going down the stairs ahead of me. I walked along to Cleats, where I had a half pint with the local SF crew, and on to the station. At Glasgow Airport I found a corner seat in Greggs, and read and dozed until it was time to join the queue. Apart from a two-hour delay in Amsterdam, the fight was uneventful. I was met by a taxi at the airport, and taken to Gothia Towers Hotel, adjacent to the venue, an enormous exhibition centre.

Erik Eje Almqvist met me in the lobby, treated me to a beer and lunch in the restaurant, and got me my guest badge and packet. The main theme of the Book Fair was Sápmi, the homeland of the Sámi people. A second theme was space. Quite a number of people in the corridors wore brightly coloured and embroidered Sámi clothing.

The room was splendid and had a spectacular view.

I had a nap, freshened up, and took the lift to the opening party. There the view was even more spectacular and even more people wore Sámi clothing. Everyone was speaking Swedish, but Erik spotted me and steered me into a conversation with a Lutheran clergywoman, so I had someone to chat with over my first glass. Later I had a couple of beers with Glenn Petersen of SF-Bokhandeln. A band played something that was meant to evoke space or cyberpunk, and Johan Stanberg McGuinne performed a joik. I was struck by some resemblances to Gaelic singing and the cadences of Highland heightened speech in preaching and poetry. Afterwards, I raised this rather tentatively with Johan, who surprised me by agreeing. Of Gaelic and Sámi heritage himself, Johan pointed out that these two cultures were unlikely to have influenced each other. An agreeable puzzle.

Thursday was one of my extra days, so after breakfast I picked up a Gothenburg tourist booklet in the hotel lobby and set off on the kind of local wander that Carol and I would have done. This included an amphibious bus tour, a late lunch of a massively filled sandwich at the food market, and a stroll through the botanic garden, which ended in me sitting on a bench and being acutely aware that Carol wasn't beside me.

I walked back to the hotel just as the rain was starting, and had a look around the book fair, which was spread across four large and crowded halls.

The following days, these halls were packed. Every day, tens of thousands of people turned up. Every publisher and, it seemed, every reader in Sweden was there. I may write more about it sometime. I had a good time, I met new people, and I met up with Alastair Reynolds, Paul McAuley and Peter Hamilton, and we had breakfasts and beers. On the last day Glenn Petersen and his wife Ylva took us and their colleagues out for dinner at a Michelin starred restaurant. I asked Ylva if she could recommend somewhere to go on Sunday, the last of the free days we'd booked, and she suggested Marstrand Island. What I wanted to do, again, was take the sort of sight-seeing trip that Carol and I would have taken if she'd been there. This sounded exactly right.

It was. The bus rides were long, but the scenery was amazing, and every bus was on time. Marstrand Island is a five-minute ferry crossing from the terminus. Its main feature is a naval fortress, which unlike many such around the world has seen action.

Going around it was a pang. In 2023, Carol and I had explored a much larger naval fortress, at Pula in Croatia. Much larger, yes, but the layout has its own logic, and every corner had a sharp memory rising unbidden around it.

The views were great. Carol would have enjoyed it, if she'd been there.

Carol's funeral [ 11-Sep-24 2:35pm ]

More people came to Carol's funeral than there were seats in the crematorium chapel: our families, her friends and mine, some of whom had travelled a long way. The funeral directors, P B Wright and Sons, took care of the arrangements kindly and professionally. Catriona Miller, the humanist celebrant, conducted the service and delivered a warm and accurate tribute to Carol. I spoke about Carol's life with me, and Michael spoke for himself and Sharon about Carol as a mother. Two hymns were sung that had also been sung at our wedding. The closing music was a song Carol had played countless times: 'Stars' by Simply Red.

The Order of Service booklet featured a fine recent photograph of Carol by Michael, and some of Carol's own photographs of Gourock's sunset skies.

The collection was for two charities that Carol had actively supported: the RNLI, and Medical Aid for Palestinians. It raised £1138.50, which yesterday I rounded up to £1200 and divided evenly into two donations in her memory.

Many, many thanks to all who attended, and to all who contributed so generously, at the collection and online. Thanks also for the many messages and cards of sympathy, for which I and all the family are deeply grateful.

# [ 28-Aug-24 9:00am ]

Carol Ann MacLeod, 11 February 1952 to 16 August 2024

Carol, my beloved wife whom I met in 1979 and married in 1981, died on Friday 16 August.

Carol, my beloved wife whom I met in 1979 and married in 1981, died on Friday 16 August.

She was the centre of my world, and she's gone.

There will be a funeral service at Greenock Crematorium, on Monday 2 September, at 2 pm, to which all family and friends are invited. Family flowers only please. There will be a retiral collection in aid of Carol's favourite charities. #

# [ 05-Aug-24 3:38pm ]

My Glasgow Worldcon Schedule

As some of you may know, I'm a Guest of Honour at the Glasgow Worldcon. I haven't said enough about that here, I know. I'm well chuffed about it, needless to say. Here are time/places where you can be sure to find me.

Autographing: Ken MacLeod, Thursday 8 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Autographs)

Opening Ceremony, Thursday 8 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Morrow's Isle - Opera, Thursday 8 August 2024, 20:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Iain Banks: Between Genre and the Mainstream, Friday 9 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Alsh 1

Luna Press Book Launch Party, Friday 9 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Argyll 2

Guest of Honour Interview: Ken MacLeod, Friday 9 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Lomond Auditorium

Table Talk: Ken MacLeod, Saturday 10 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Table Talks)

The Making of Morrow's Isle - An Opera, Saturday 10 August 2024, 14:30 GMT+1, Argyll 2

NewCon Press Book Launch, Saturday 10 August 2024, 16:00 GMT+1, Argyll 3

The Politics of Modern Scottish SF, Saturday 10 August 2024, 20:30 GMT+1, Castle 1

Reading: Ken MacLeod, Sunday 11 August 2024, 10:00 GMT+1, Castle 2

Autographing: Ken MacLeod, Sunday 11 August 2024, 11:30 GMT+1, Hall 4 (Autographs)

An Ambiguous Utopia: 50 Years of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed, Sunday 11 August 2024, 14:30 GMT+1, Meeting Academy M1

2024 Hugo Awards Ceremony, Sunday 11 August 2024, 20:00 GMT+1, Clyde Auditorium

Stroll with the Stars - Monday, Festival Park, Monday 12 August 2024, 09:00 GMT+1, Outside Crowne Plaza

Writing Future Scotland, Monday 12 August 2024, 13:00 GMT+1, Lomond Auditorium

#

This historic Worldcon has already been very well covered by others, e.g. Nicholas Whyte and Jeremy Szal. For lots of coverage of events, guests and so on, see the con's Facebook page.

But I've been back over a week, and here's my overdue account.

Last month I spent far too few days in China, at the Chengdu Worldcon, to which I was invited as an international guest. My travel, and accommodation for me and my wife, were covered by the Committee of the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention, for which much thanks.

We had a wonderful time. The convention was a smashing success and easily the biggest, and most publicly celebrated, Worldcon ever.

We arrived at Chengdu airport in the early evening of Wednesday 18 November and quickly met volunteers at a stall near the exit, from which were immediately hurried to a minibus that took us to the Sheraton Pidu. Along the way we saw advertisements for the Chengdu Worldcon lining the highways, and the robot panda mascot at numerous intersections. We met the volunteer who was looking after us, Zoe, who was unfailingly sweet and helpful throughout. Our luggage was whisked inside and we were back on a bus for a short drive to the venue.

This was the elegant and futuristic newly built Chengdu Science and Science Fiction Museum, across a lake in the park from the hotel. We took our seats just in time for the start of the opening ceremony.

This was the elegant and futuristic newly built Chengdu Science and Science Fiction Museum, across a lake in the park from the hotel. We took our seats just in time for the start of the opening ceremony.

This combined a traditional Worldcon opening ceremony...

...with a spectacular show, including song and dance, giant video projections, and culminated in a drone display outside the huge semi-circular window of astronomical and sci-fi images whose high point was an outline rendering of a spinning black hole (which unfortunately I didn't catch, so you'll have to make do with Saturn).

...with a spectacular show, including song and dance, giant video projections, and culminated in a drone display outside the huge semi-circular window of astronomical and sci-fi images whose high point was an outline rendering of a spinning black hole (which unfortunately I didn't catch, so you'll have to make do with Saturn).

The other ceremonies - the Galaxy Awards, the opening of the Chengdu International Science Fiction convention, the Hugo Awards, the Hugo after-party, and the closing ceremony - were likewise spectacular: a primary school choir sang in one of these, an entire symphony orchestra took the stage in another, and so on.

They were MC'd by professional television presenters.

They were MC'd by professional television presenters.

The venue was as impressive inside as outside.

The venue was as impressive inside as outside.

I took part in a couple of panels, one on Science Fiction and Future Science and one on cyberpunk, and was interviewed on video by an Italian documentary company and on voice recording for the Huawei news website. For two mornings I put in an hour or two at the Glasgow Worldcon stand. Never in my life have I been asked for so many autographs, or to pose with so many people for photographs. Nicholas Whyte, also at the stall, had the same experience, and others did too. Hardly any of the people whose notebooks and souvenirs we signed, or who stood beside us to have their photo taken, could have known who we were: that were overseas visitors with something to do with science fiction was enough. Among the few who did know us were some students from the Fishing Fortress College of Science Fiction in Chongqing.

Our enthusiastic reception was nothing to that of Cixin Liu, author of the Three-Body trilogy and the story filmed as The Wandering Earth. His signing queue was like those I've seen for Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Science fiction in China is taken very seriously and sincerely by its fans.

I took part in a couple of panels, one on Science Fiction and Future Science and one on cyberpunk, and was interviewed on video by an Italian documentary company and on voice recording for the Huawei news website. For two mornings I put in an hour or two at the Glasgow Worldcon stand. Never in my life have I been asked for so many autographs, or to pose with so many people for photographs. Nicholas Whyte, also at the stall, had the same experience, and others did too. Hardly any of the people whose notebooks and souvenirs we signed, or who stood beside us to have their photo taken, could have known who we were: that were overseas visitors with something to do with science fiction was enough. Among the few who did know us were some students from the Fishing Fortress College of Science Fiction in Chongqing.

Our enthusiastic reception was nothing to that of Cixin Liu, author of the Three-Body trilogy and the story filmed as The Wandering Earth. His signing queue was like those I've seen for Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Science fiction in China is taken very seriously and sincerely by its fans.

Thousands upon thousands of people passed through the venue, including many primary-school classes there for the day. Lots of young people, and lots of families. They weren't just there for the toys and for the impressive tech exhibition hall.

The bookstall just across from the Glasgow Worldcon stall had a fast-moving queue of book-laden customers all the time. Many panels were standing room only, with people crowding the doorway leaning in and recording on their phones.

The bookstall just across from the Glasgow Worldcon stall had a fast-moving queue of book-laden customers all the time. Many panels were standing room only, with people crowding the doorway leaning in and recording on their phones.

There were hundreds of volunteers, some minding the international guests, others helping visitors to the venue, acting as guides in exhibitions, or adding some elegance to the ceremonies.

Some even worked on security (the hotel and the venue had almost airport-level security throughout the convention). Most seemed to be from language schools, and eager to practice their English.

Some even worked on security (the hotel and the venue had almost airport-level security throughout the convention). Most seemed to be from language schools, and eager to practice their English.

Our good friend Fan Zhang, who looked after us so well in Beijing in 2019, now has an important post at the Fishing Fortress college of Science Fiction. He took us out to dinner with two of his staff, and had some interesting proposals for next year, which I'm seriously considering.

We had one side trip organised by the convention for guests: a visit to Chengdu's famous panda research centre, truly unforgettable.

Alongside the hotel was an exhibition of 'Intangible Cultural Heritage', traditional arts and crafts: Shu embroidery not just displayed but demonstrated, traditional music and singing, silver filigree, a tea ceremony, cut-paper pictures, and melted-sugar drawings made before our eyes and handed to us on a stick to eat. It all made for an interesting and uplifting hour.

Alongside the hotel was an exhibition of 'Intangible Cultural Heritage', traditional arts and crafts: Shu embroidery not just displayed but demonstrated, traditional music and singing, silver filigree, a tea ceremony, cut-paper pictures, and melted-sugar drawings made before our eyes and handed to us on a stick to eat. It all made for an interesting and uplifting hour.

On our final day, Monday 23 October, Carol and I went on our own to the Wuhou Shrine, a historic site and major tourist destination set in a great park which opens to some old streets, now lined with gift shops and street food stalls.

And on Tuesday we began the long journey home. We had met old friends and made new ones, and it was a pang to leave.

We owe thanks to many people - the organisers and volunteers, especially Zoe, and a special thanks to the indefatigable Sara Chen.

Cosmia Festival [ 20-Apr-23 11:57am ]

On Saturday I'll be at the Cosmia Festival in Huddersfield. I have a talk about my recent and current books (4:45pm to 5:45pm), and from 7pm to 8:15pm I'll be talking about Iain M. Banks along with his 9and my) friend and musical collaborator, Gary Lloyd.

£10 for the day, with a great range of authors, plus workshops and exhibitions: details and bookings here.

14-Apr-23

£10 for the day, with a great range of authors, plus workshops and exhibitions: details and bookings here.

Moniack in a Month - Writing Science Fiction [ 14-Apr-23 2:58pm ]

I'm delighted to say that bookings are now available for an online course on writing science fiction which I'll be teaching this September. Details are here. The wonderful Justina Robson has kindly agreed to be our Guest Reader.

Lightspeed trilogy publication news: UK and US [ 27-Mar-23 5:30pm ]

Last week saw the UK publication of my new novel, Book Two of the Lightspeed trilogy, BEYOND THE REACH OF EARTH, available here from Amazon UK.

A day later came the US publication of the first book, BEYOND THE HALLOWED SKY, by Pyr Books and available via Simon and Schuster, with links to Amazon and other online bookshops.

This book has had kind words from North American authors:.jpg)

22-Jan-23

A day later came the US publication of the first book, BEYOND THE HALLOWED SKY, by Pyr Books and available via Simon and Schuster, with links to Amazon and other online bookshops.

This book has had kind words from North American authors:

Ken Macleod does things nobody else does and this is a terrific read.- Jo Walton, multi-award-winning author of Among Others and What Makes This Book So Great

Sure, some writers knock it out of the park but with Beyond the Hallowed Sky, Ken MacLeod knocks it right out of the solar system! Too often, space opera throws science out the airlock, but MacLeod has given us a believable faster-than-light adventure that will have you racing through the pages at superluminal speed.- Robert J. Sawyer, Hugo Award-winning author of The Oppenheimer Alternative

An exceptional blend of international politics, hard science, and first contact.

- Michael Mammay, author of the Planetside series.

.jpg)

I haven't been blogging much, and I hope to do more this year. There are one or two exciting publication announcements in the pipeline. In the meantime, here's a recent interview with the incredibly productive Moid of Media Death Cult, in which I talk about books I've read and books I've written, from my office which (New Year resolution!) needs some tidying.

27-Apr-22

Address to the Edinburgh Science Festival Church Service 2022 [ 27-Apr-22 4:33pm ]

The Edinburgh Science Festival closes with a church service in the historic St Giles' Cathedral. It includes a ten-minute non-religious, non-political address. This year I was honoured to be asked to give it. As you can see, the service is as splendid as the setting. My talk starts at 33:28. The text follows below.

The theme of this year's Science Festival is Revolution. This is an apt topic here in St Giles, which after all is the very spot where the revolution, in the then Three Kingdoms, began: a revolution that created modern Britain. But whether Jennie Geddes is real or legendary, I hope no chairs are hurled at the pulpit today. So, steering well clear of religion or politics, I'd like to talk about how we talk about politics, and when and why people started talking about revolution. Interestingly enough, it was at about the same time that our revolution happened, in the seventeenth century.

In the same century, and perhaps by no coincidence, there was a scientific revolution. The mechanics of Galileo and Newton was the subversive science of its day, challenging the metaphysical doctrines of ancient tradition as shatteringly as the artillery it helped to aim battered down the walls of lordly castles. And it left its mark on our language of politics.

When you look at the language and vocabulary that we use to describe political events, you find a surprising number of words from seventeenth-century physics and astronomy. Revolution in that context meant a complete turning of a wheel, or the circuit of a planet in its orbit - the revolutions of the heavenly bodies, as Copernicus titled his revolutionary thesis. And revolution, as a metaphor in politics, originally meant something very similar - a return to the starting point.

At the time it must indeed have seemed like that. You get rid of a King, you fight a civil war and end up with a Protector, and then the Protector dies and before you know it you have a King again. And everything seems to be back in the same place as it was before: after the Interregnum, the Restoration. Looking back, people in later centuries could see more clearly that it was not: that some things had changed irreversibly, and the revolution, you might say, kept rolling on.

We still talk of masses, which may or may not be in motion. We speak of political and social movements, which may or may not have certain dynamics. We evaluate the balance of forces. If we're politics professors or journalists, we may ponder the electoral cycle. We may look at a social or political system - and that word too, system, originates in astronomy - and ask whether the system is stable or unstable, or whether or not it is in equilibrium. We may investigate the system's mechanics. We may despair at the system's inertia, and hope, perhaps in vain, for some impulse or even momentum to change it. And can the change we seek or fear be accelerated, or retarded? Should we worry about possible retrograde developments? Will our action in the end produce a reaction?

It's Newtonian mechanics all the way down! Well - perhaps not quite. There are some other sciences that we draw on for political metaphor: the idea of a political upheaval surely comes from geology, as does a political earthquake, when the tectonic plates of politics shift. (I wonder how many years of the Edinburgh Science Festival, and how much toil of primary and secondary school teachers, and how many school visits to Dynamic Earth it took before plate tectonics became a political metaphor that everyone could understand!)

Our most troubling political language comes from biology, and evolutionary biology in particular. The metaphors of competition, of natural selection, of struggles for existence have been applied and misapplied with dire consequences. This pains me greatly, not least because I trained as a zoologist. Now, I've read Darwin, and for my sins I've even read Herbert Spencer, and I can honestly say that in these matters they are both much maligned. There is no basis in their work, let alone in modern biology, for any kind of racial politics. But when the founding text of a discipline is titled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life it's all too easy to see how misunderstandings could arise.

Is there a biological science that might offer us a more fruitful language for politics? I think there is: ecology. It's already provided us with two familiar terms in politics: sustainability, and diversity. Ecology examines all forms of life in interaction with their physical environment and with each other, and identifies and measures the flows of energy and material among them. And humanity, of course, is now a somewhat important form of life, and affects these flows on a planetary scale, not always entirely for the good of itself, let alone the rest.

Ecology, I think, is as subversive a science in our time as Newton's mechanical philosophy was in his. Why? It delivers warnings about what our interactions with the rest of nature are doing to us and to the planet, certainly. But it does more. It suggests a science of ourselves that starts with our relationship with the rest of nature, and with each other. Like it or not, we all need food, drink, and shelter, and like it or not we can only get them from the rest of nature and in and through relationships with other people. Human beings can't sustain themselves individually, like the sea-birds outside my window, or co-operate instinctively, like the ants in my back yard. We're social and productive by necessity but not by instinct, so we must rely on thought and speech. To make our living together, we have to speak and think, imagine and create, question and discover. An ecologically inspired science of humanity could start from these facts, and trace the flows of material and energy through human society and back to the earth and air and water around us. It could ask what people think they're doing, and investigate what they're actually doing. It might dig up all kinds of inconvenient truths about where stuff comes from, where it goes, and how it gets there -- and who gets it, and who gives. And if these connections became widely known and understood, people might want to change a lot of what goes on.

Perhaps we need a better metaphor for change than revolution. One that has always stuck in my mind is ecological succession. On land left bare by ice or fire or landslide or flood, different populations of plants, animals and fungi settle in well-defined stages, each incomplete and unstable in itself, each more complex and diverse in its components and their interactions, until finally there arises what is called the climax community, a combination of species that is self-sustaining and self-reproducing: a mature forest, for example. The more complex and various the community, the more stable and resilient it is. Is such complexity and diversity, then, that we should expect and work towards in our human community? What would a climax community of humanity look like? Are we there yet? I'll leave these questions open. I'm not here to preach.

08-Mar-22

The theme of this year's Science Festival is Revolution. This is an apt topic here in St Giles, which after all is the very spot where the revolution, in the then Three Kingdoms, began: a revolution that created modern Britain. But whether Jennie Geddes is real or legendary, I hope no chairs are hurled at the pulpit today. So, steering well clear of religion or politics, I'd like to talk about how we talk about politics, and when and why people started talking about revolution. Interestingly enough, it was at about the same time that our revolution happened, in the seventeenth century.

In the same century, and perhaps by no coincidence, there was a scientific revolution. The mechanics of Galileo and Newton was the subversive science of its day, challenging the metaphysical doctrines of ancient tradition as shatteringly as the artillery it helped to aim battered down the walls of lordly castles. And it left its mark on our language of politics.

When you look at the language and vocabulary that we use to describe political events, you find a surprising number of words from seventeenth-century physics and astronomy. Revolution in that context meant a complete turning of a wheel, or the circuit of a planet in its orbit - the revolutions of the heavenly bodies, as Copernicus titled his revolutionary thesis. And revolution, as a metaphor in politics, originally meant something very similar - a return to the starting point.

At the time it must indeed have seemed like that. You get rid of a King, you fight a civil war and end up with a Protector, and then the Protector dies and before you know it you have a King again. And everything seems to be back in the same place as it was before: after the Interregnum, the Restoration. Looking back, people in later centuries could see more clearly that it was not: that some things had changed irreversibly, and the revolution, you might say, kept rolling on.

We still talk of masses, which may or may not be in motion. We speak of political and social movements, which may or may not have certain dynamics. We evaluate the balance of forces. If we're politics professors or journalists, we may ponder the electoral cycle. We may look at a social or political system - and that word too, system, originates in astronomy - and ask whether the system is stable or unstable, or whether or not it is in equilibrium. We may investigate the system's mechanics. We may despair at the system's inertia, and hope, perhaps in vain, for some impulse or even momentum to change it. And can the change we seek or fear be accelerated, or retarded? Should we worry about possible retrograde developments? Will our action in the end produce a reaction?

It's Newtonian mechanics all the way down! Well - perhaps not quite. There are some other sciences that we draw on for political metaphor: the idea of a political upheaval surely comes from geology, as does a political earthquake, when the tectonic plates of politics shift. (I wonder how many years of the Edinburgh Science Festival, and how much toil of primary and secondary school teachers, and how many school visits to Dynamic Earth it took before plate tectonics became a political metaphor that everyone could understand!)

Our most troubling political language comes from biology, and evolutionary biology in particular. The metaphors of competition, of natural selection, of struggles for existence have been applied and misapplied with dire consequences. This pains me greatly, not least because I trained as a zoologist. Now, I've read Darwin, and for my sins I've even read Herbert Spencer, and I can honestly say that in these matters they are both much maligned. There is no basis in their work, let alone in modern biology, for any kind of racial politics. But when the founding text of a discipline is titled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life it's all too easy to see how misunderstandings could arise.

Is there a biological science that might offer us a more fruitful language for politics? I think there is: ecology. It's already provided us with two familiar terms in politics: sustainability, and diversity. Ecology examines all forms of life in interaction with their physical environment and with each other, and identifies and measures the flows of energy and material among them. And humanity, of course, is now a somewhat important form of life, and affects these flows on a planetary scale, not always entirely for the good of itself, let alone the rest.

Ecology, I think, is as subversive a science in our time as Newton's mechanical philosophy was in his. Why? It delivers warnings about what our interactions with the rest of nature are doing to us and to the planet, certainly. But it does more. It suggests a science of ourselves that starts with our relationship with the rest of nature, and with each other. Like it or not, we all need food, drink, and shelter, and like it or not we can only get them from the rest of nature and in and through relationships with other people. Human beings can't sustain themselves individually, like the sea-birds outside my window, or co-operate instinctively, like the ants in my back yard. We're social and productive by necessity but not by instinct, so we must rely on thought and speech. To make our living together, we have to speak and think, imagine and create, question and discover. An ecologically inspired science of humanity could start from these facts, and trace the flows of material and energy through human society and back to the earth and air and water around us. It could ask what people think they're doing, and investigate what they're actually doing. It might dig up all kinds of inconvenient truths about where stuff comes from, where it goes, and how it gets there -- and who gets it, and who gives. And if these connections became widely known and understood, people might want to change a lot of what goes on.

Perhaps we need a better metaphor for change than revolution. One that has always stuck in my mind is ecological succession. On land left bare by ice or fire or landslide or flood, different populations of plants, animals and fungi settle in well-defined stages, each incomplete and unstable in itself, each more complex and diverse in its components and their interactions, until finally there arises what is called the climax community, a combination of species that is self-sustaining and self-reproducing: a mature forest, for example. The more complex and various the community, the more stable and resilient it is. Is such complexity and diversity, then, that we should expect and work towards in our human community? What would a climax community of humanity look like? Are we there yet? I'll leave these questions open. I'm not here to preach.

BEYOND THE HALLOWED SKY is a Kindle Daily Deal today [ 08-Mar-22 11:21am ]

12-Dec-21

BEYOND THE HALLOWED SKY [ 12-Dec-21 3:01pm ]

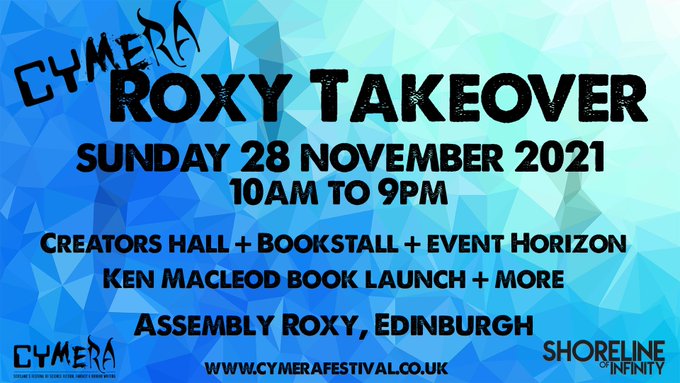

What with one thing and another I've neglected to mention here that my new novel, Beyond the Hallowed Sky, has been published. It has been well received so far, with good reviews in The Scotsman/Scotland on Sunday and SFX. The book launch at the Cymera mini-festival, in the form of an onstage conversation with Professor Ruth Aylett, went well. You can read the first chapter of the book here.

It's the first volume of the Lightspeed Trilogy, and the second volume is well underway.

03-Dec-21

It's the first volume of the Lightspeed Trilogy, and the second volume is well underway.

What does fiction tell us about our hopes and fears for technology? [ 03-Dec-21 4:44pm ]

I'm delighted to say I'm on an online panel at the Digital Ethics Summit 2021, with Tabitha Goldstaub, Professor Sarah Dillon, and Ted Chiang.

4.30pm - 5.05pm GMT, 8 December 2021.

Register for free here.

22-Nov-21

4.30pm - 5.05pm GMT, 8 December 2021.

Register for free here.

Book launch for BEYOND THE HALLOWED SKY [ 22-Nov-21 1:50pm ]

21-Aug-21

'Nineteen Eighty-Nine' [ 21-Aug-21 8:32pm ]

I'm very happy to say that I have a short story, 'Nineteen Eighty-Nine', in the first issue (Autumn 2021) of the new online science fiction, fantasy and horror magazine ParSec, edited by Ian Whates, now available here from PS Publishing .

The story has been long in the making. Sometime in the early 1990s I had an idea for a story called 'Nineteen Eighty-Nine', in which events like those of 1989 in our world happen in the world of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. I wrote it and sent it to Interzone, and they sent me a kind rejection note suggesting that I try a local fanzine. I sent it to the local fanzine New Dawn Fades, and they rejected it. The editor softened the blow by encouraging me to write something else for them. They later accepted, I think, a review and a poem. But for the moment, I was done with short stories. After that, there was nothing for it but to write a novel.

That's the story I've told now and again, usually with the punch-line that the best thing about the story was the title, because it tells you exactly what the story is about.

Now I'm going to have to retire that anecdote.

Earlier this year, shortly after I had read that Orwell's fiction was now out of copyright, Ian Whates emailed me to ask for a story for a new venture he was planning. I pitched 'Nineteen Eighty-Nine'. Ian was keen, so I looked at my old story (or what I could find of it), decided it was beyond help, and wrote an entirely new story. I'm fairly sure it's an improvement on my first attempt.

One inspiration for the new version was the article 'If there is Hope' by Tony Keen, in Journey Planet #3 (pdf). Another was the article Orwell on Workers and Other Animals, by Gwydion M. Williams, which makes the intriguing point that 1945 is missing from the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

While writing the story I chanced on a clue to Orwell's pessimism that, as far as I know, has escaped scholarly attention. Orwell, it turns out, had read and been impressed by George Walford's pamphlet The Intellectual and the People.

Walford drew on his mentor Harold Walsby's The Domain of Ideologies, the founding text of what Walford later called Systematic Ideology. This argued that the major social outlooks form a historical, numerical, and political series in decreasing order of antiquity, size, unity, and radicalism. The (historically) oldest and (currently) largest group is the apolitical, followed by the conservative, the reformist, the revolutionary, and the anarchist ... with the tiniest, least effectual and most extreme group being the Systematic Ideologists themselves, who understand the whole process but can't think what to do about it.

More about this another time, but it seems to me significant that Orwell attributed political apathy, ignorance and indifference to - not 'perhaps the largest single group' of the population, as Walford did - but to the vast majority: 85%.

04-Oct-20

The story has been long in the making. Sometime in the early 1990s I had an idea for a story called 'Nineteen Eighty-Nine', in which events like those of 1989 in our world happen in the world of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. I wrote it and sent it to Interzone, and they sent me a kind rejection note suggesting that I try a local fanzine. I sent it to the local fanzine New Dawn Fades, and they rejected it. The editor softened the blow by encouraging me to write something else for them. They later accepted, I think, a review and a poem. But for the moment, I was done with short stories. After that, there was nothing for it but to write a novel.

That's the story I've told now and again, usually with the punch-line that the best thing about the story was the title, because it tells you exactly what the story is about.

Now I'm going to have to retire that anecdote.

Earlier this year, shortly after I had read that Orwell's fiction was now out of copyright, Ian Whates emailed me to ask for a story for a new venture he was planning. I pitched 'Nineteen Eighty-Nine'. Ian was keen, so I looked at my old story (or what I could find of it), decided it was beyond help, and wrote an entirely new story. I'm fairly sure it's an improvement on my first attempt.

One inspiration for the new version was the article 'If there is Hope' by Tony Keen, in Journey Planet #3 (pdf). Another was the article Orwell on Workers and Other Animals, by Gwydion M. Williams, which makes the intriguing point that 1945 is missing from the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

While writing the story I chanced on a clue to Orwell's pessimism that, as far as I know, has escaped scholarly attention. Orwell, it turns out, had read and been impressed by George Walford's pamphlet The Intellectual and the People.

Walford drew on his mentor Harold Walsby's The Domain of Ideologies, the founding text of what Walford later called Systematic Ideology. This argued that the major social outlooks form a historical, numerical, and political series in decreasing order of antiquity, size, unity, and radicalism. The (historically) oldest and (currently) largest group is the apolitical, followed by the conservative, the reformist, the revolutionary, and the anarchist ... with the tiniest, least effectual and most extreme group being the Systematic Ideologists themselves, who understand the whole process but can't think what to do about it.

More about this another time, but it seems to me significant that Orwell attributed political apathy, ignorance and indifference to - not 'perhaps the largest single group' of the population, as Walford did - but to the vast majority: 85%.

Vaping and viruses [ 04-Oct-20 3:44pm ]

'Somebody died fae vaping. Yir better aff back on the fags.'

--- Lady at bus stop, a few months ago.

You might think it bad taste to talk about vaping in the middle of a pandemic, and you'd be right. But this hasn't stopped a slew of public health bodies, politicians, and activists from doing just that, so I see no reason to unilaterally disarm.

I've been meaning to blog about vaping for a while. My Twitter feed sometimes seems to be about little else, rather to my embarrassment whenever I scroll through it. So I'll start by explaining why it matters to me. As with many vapers, my story begins with smoking.

To cut that long story short: I smoked, first a pipe then cigarettes, from my early twenties to my late fifties. I tried to quit many times. The annual ratchet of tax rises in the Budget reliably brought on another attempt. Surely I'll stop, I told myself, when they're over 50p a pack! Not even the £10 pack did the trick. Neither did Allen Carr's book, willpower, shame, and the pub smoking ban. One day about ten years ago I saw an electronic cigarette in a petrol station, and bought it. It was shaped like a cigarette and had a tip that glowed when you drew on it. After buying a few of these and finding it inconvenient when they ran down I soon was ordering the same brand with rechargeable batteries and replaceable cartridges. I was still smoking cigarettes, but a bit less than before, and the ecig made pub conversations much more convivial and less often interrupted than they'd become. The kick was feeble, the nicotine faint, the taste indifferent, but it was better than nothing.