It is my pleasure to publish this extract from Gillian Tindall's novel Journal of a Man Unknown which describes a nocturnal vision that is granted to the protagonist in Mile End

CLICK HERE TO ORDER JOURNAL OF A MAN UNKNOWN FOR £10

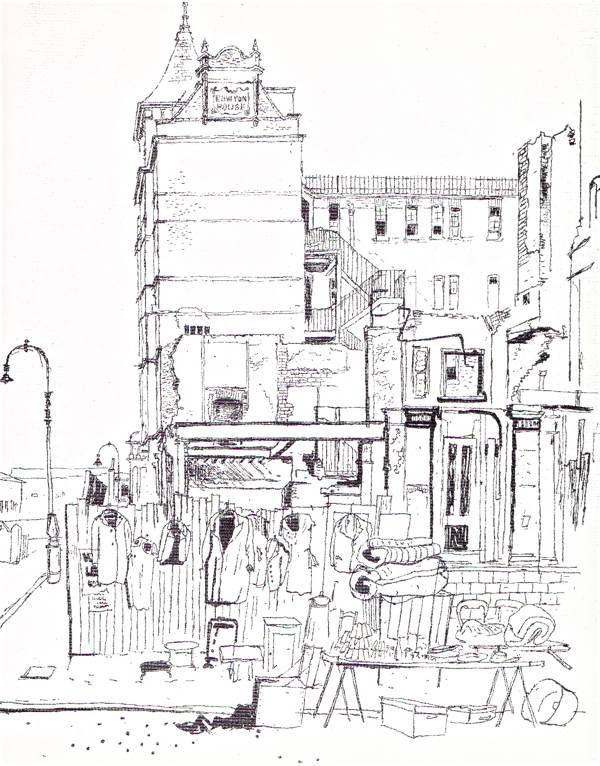

'It was a fine night, though chill, and the stars were out. I went walking on, beyond the Spital Fields and Brick Lane, out into the countryside to Mile End and beyond, to where there were few houses along the highway, out to where the Jews have made a burial ground. (I had met a few, newcomers to London like to the Huguenots, and they were very much the same manner of decent, hard-working people, for all their Spanish names). I had my knife in my belt as usual, but there was nothing to fear that far east out of Town: no-one about at all.

The moon was shining over St Dunstan's, out at Stepney, and I lent a while against the dead Jews' wall, watching it. I even contemplated walking yet further, so full of a strange energy did I feel. It was as if something that had been in the bottom of my mind for years, vaguely troubling me from time to time but ever quietly dismissed, had suddenly risen to the top that evening like liquid over a fire in a pan.

Jews, I know, have their own God whose son has yet to appear on earth. The Saracens have another one, of much the same kind by all accounts. The Huguenots, Protestants, Puritans, Catholics, Greek Christians and all the rest are supposed to believe in One God and His Son, but that has not stopped them from fighting and killing each other in the most un-Christian way in every century of which I have heard account. They were at it here in England all my childhood years.

How much fervent, angry, desperate praying goes on by all sides, many of the prayer-sayers wishing damnation on the others. And how little of it ever truly produces a result, except by ordinary life chances that are then falsely claimed as 'prayers answered'?

And in that moment I knew, in a burst of freedom, like a man before whom a door that he believed firmly locked and forbidden is suddenly open - that I did not believe in any of it, and had not done so for many years.

And as for the idea that the great Maker of the construction is perpetually watching each of us separate persons, intent on testing every one of his multitudinous subjects' loyalty with particular troubles and griefs, like a bad tempered and unjust King doling out unmerited torments to some on purpose to 'try them', while occasionally and unexpectedly bestowing blessings on others no more deserving - this was suddenly revealed to me as a story for badly behaved children.

And I strongly suspected in that same moment, that a number of the men whom I had met in London, and whom I most respected, had secretly come to the same never-to-be-spoken conclusion. Unbelief is contrary to the Law of both God and Man. But surely honest.

I went on standing there for quite a while, I think, trying to take in my new-found freedom. It felt right and just. But lonely, if - from - henceforth, there were none but myself in charge of my fate. Also a sense of my consequent, helpless separation in my secret heart from all others. For a few minutes my desolation recalled my first weeks alone in London. And I had no one at that time with whom I felt intimate enough to admit my new conviction.

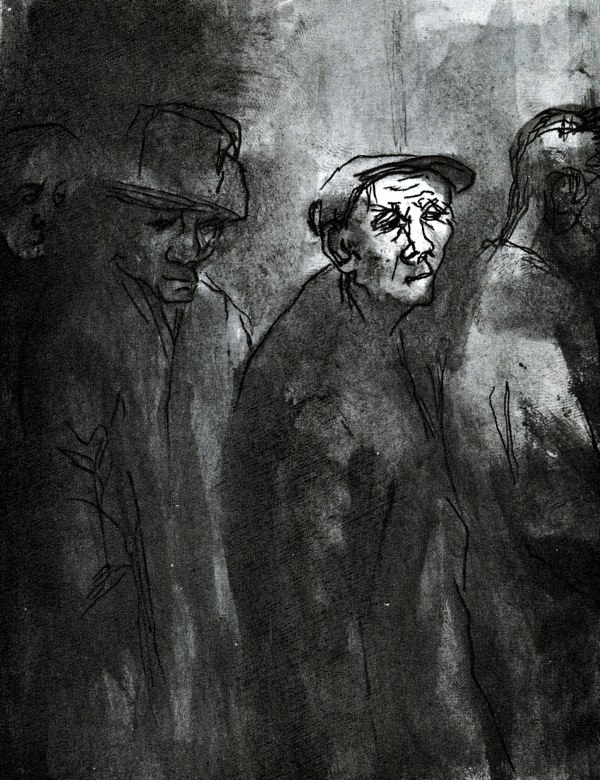

And then something odd happened while I stood there. One of those moments, like the one in the night before I left the Forest (which I had dismissed as a dream). Although the Mile End Road was deserted, the few cottages around shuttered and none about but a half-grown fox in the Jews' cemetery, who had caught sight of me over the wall and had scampered away, I suddenly became convinced that I was surrounded. By houses and people that I could sense but could not see. The moon at that moment had gone behind a thick cloud, a country-dark descended. Yet I felt as if I were standing in a City street. Voices, passing by, that I could not hear properly, and footsteps on stone and other sounds of rushing or roaring that I could not identify. Such as the sound of machines. But my strongest sensation was that I was hemmed in, crowded.

Cravenly fearful, as if my ungodly thoughts were somehow visiting on me a revenge, I clutched the top of the brick cemetery wall with my hands. That at least seemed solid and of all time. Fearful of what the returning moon might reveal, I shut my eyes for a while. I believe that by habit I even cravenly and illogically prayed 'Keep me safe, Lord!'

I opened my eyes again at last when the sounds had faded away. The moon had returned. The Mile End Road was its peaceful, deserted, night-time self. The clock of St Dunstan's struck twelve.

Suddenly very tired, I must have made my way back to the Spital Fields, though that I do not remember.'

CLICK HERE TO ORDER JOURNAL OF A MAN UNKNOWN FOR £10

This is one of three monster pumps whose purpose is to maintain the water level in the West India Dock at Canary Wharf. Coiled up like giant sea serpents, these mysterious green creatures inhabit an impounding station built where the dock meets the Thames at Limehouse. From the exterior, this old brick shed reveals nothing of its function, yet once you step inside you enter another realm where the pumps line up dutifully to serve their purpose, like cows in a milking shed or horses in a stable. It is quite an adventure to climb down the stairs into the vast industrial space that houses the mighty pumps and discover that the building is much larger than it looks on the outside.

Built in the twenties and opened in 1930, the West India Docks Impounding Station is a shining marvel of engineering that is maintained in constant good working order today by the Canal & River Trust. Gauges measure the water in the dock and, if it drops below the desired level, the electric pumps automatically whirr into action to top it up, drawing water from the Thames. Usually only one of the pumps is required, with another as a back-up and a spare in case one of the others breaks down. All eventualities are covered.

When the to-and-fro of the ships from the docks into the tidal Thames caused the water level in the docks to fall, the impounding station became necessary to ensure that the water was kept at sufficient level to prevent grounding of vessels in the dock. On the day I visited, our guide took us first to gaze in wonder upon the great expanse of water in the dock hemmed on all sides by tall towers and explained - to my alarm - that if all the water drained out of the dock then the buildings might fall down. I was marginally relieved when it was explained to me later that, when the docks were constructed two centuries ago, they were built with bevelled brick walls which make them exceptionally robust structurally.

I do wonder if the guide had been pulling my leg about the towers at Canary Wharf collapsing if the water drained out, but I take reassurance in the continued existence of the impounding station to ensure that I will never find out the truth, or otherwise, of this apocalyptic supposition.

The anonymous exterior of the West India Docks Impounding Station

'You climb down the stairs into an industrial space and discover that the building is much larger than it looks on the outside'

'The pumps line up dutifully to serve their purpose, like cows in a milking shed or horses in a stable'

'Coiled up like giant sea serpents'

These contains blades that may be lowered or raised to control the ingress of water into the dock

Maintenance tools from 1930

Entrance to West India Docks, originally built as the City Canal in 1805 and then sold to West India Dock Company in 1829 to construct the dock.

Carved numerals indicate the water level at the entrance to the dock

Looking west up the Thames from the dock entrance at Limehouse

West India Docks is surrounded by tall towers today

Contact the Canal & River Trust to find out when the Impounding Station my be visited

Remembering Stanley Rondeau who died on 13th January aged ninety-two

Stanley Rondeau's great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Jean Rondeau was a Huguenot silk weaver who came to Spitalfields in 1685 as a refugee fleeing religious persecution in Paris. Jean's son prospered in Spitalfields, becoming Sexton at Christ Church, having eleven children, building a new house at 4 Wilkes St and commissioning designs in the seventeen-forties from the most famous of silk designers, Anna Maria Garthwaite, who lived almost next door, in the house on the corner with Princelet St.

Since Anna Maria Garthwaite's designs were exceptionally prized both for their aesthetic appeal and their functional elegance as patterns for silk weaving, hundreds of her original paintings have survived to this day. So Stanley & I went along to the Victoria & Albert Museum in Kensington to take a look at those done for Stanley's ancestor Jean the Sexton, nearly three centuries ago. We negotiated our way through the labyrinths of the vast museum, teeming with school children, with a growing sense of anticipation because although Stanley had seen one of the designs reproduced in a book, he had never cast his eyes upon the originals. And up on the fourth floor, we entered a sanctuary of peace and quiet where curator Moira Thunder awaited us in a lofty room with a long table and large flat blue boxes containing the treasured designs that were the objects of our quest.

Moira - chic in contrasting tones of plum and navy blue, and with a pair of fuchsia lenses which hinted at a bohemian side - welcomed us with scholarly grace, and duly opened up the first box to reveal the first of Anna Maria Garthwaite's designs. Drawn in the wide margin at the top of a large sheet containing an elaborate floral number, this design was the epitome of restraint with a repeated motif that resembled a bugle flower in subdued tones of purplish brown, labelled Mr Rondeau, Feb 5 174 1/2, and intended as a pattern to be woven into the body of a vellure used for men's suiting.

Stanley was instinctively drawn towards his own name revealed before him, leaned forward to touch the piece of paper - which caused Moira's eyes to pop, though fortunately for all concerned the priceless design was protected by a layer of transparent conservator's plastic. Once smiles of amelioration had been exchanged after this faux-pas, Stanley enjoyed a quiet moment of contemplation, gazing with his deep-set chestnut eyes from beneath his bushy white eyebrows upon the same piece of paper that his ancestor saw. I think Stanley would have preferred it if 'Mr Rondeau' had been written beside the fancy design below, because he asked Moira whether the other design for Jean Rondeau in the collection was more colourful but, with an unexpectedly winsome smile, Moira refused to be drawn.

Yet while Stanley's curiosity was understandably focussed upon those designs attributed to his ancestor, I was enraptured by the myriad pages of designs by Anna Maria Garthwaite, whose house I walk past every day. Kept from the daylight, the colours in these sketches remain as fresh as the day she painted them in Spitalfields three centuries ago. The accurate observation of both cultivated and wild flowers in these works suggests they were painted from specimens which permits me to surmise that she had access to a garden, and picked her wild flowers in the fields beyond Brick Lane. I especially admired the sparseness of these sprigged designs, drawing the eye to the lustrous quality of the silk, and Moira, who worked as assistant to Natalie Rothstein - the ultimate authority on Spitalfields silk - pointed out that weavers rarely deviated from Garthwaite's designs because they were conceived with such thorough understanding of the process.

And then, Moira opened the second box to reveal the second design by Anna Maria Garthwaite for Jean Rondeau, which Stanley had never seen before. Larger and more complex than the previous, although monochromatic, this was a pattern of pansy or violet flowers divided by scalloped borders into a repeated design of lozenges. Again drawn in the margin, at the top of a piece of paper above a multicoloured design, this has the name 'Mr Rondeau' written in feint pencil beside it. It was a design for a damask, either for men's suiting or a woman's dress, which Moira suggested would be appropriate to be worn at the time of half-mourning. A degree of formalised grief that is unfamiliar to us, yet would have been the custom in a world where women bore many more babies in the knowledge that only those chosen few would survive beyond childhood.

Moira took the unveiling of this second design as the premise to outline the speciality of Master Silk Weaver Jean Rondeau, who appears to have built his fortune, and company of fifty-seven employees, upon the production of cheaper silks for men, unlike his Spitalfields contemporary Captain Lekeux - for whom Anna Maria Garthwaite also designed - who specialised in the most expensive silks for women. In response to Moira's erudition, Stanley began to talk about his ancestor and the events of the seventeen forties in Spitalfields with a familiarity and grasp of detail that made it sound as if he were talking about a recent decade. And as he spoke, with the unique wealth of knowledge that he had gathered over a lifetime of research, I could see Moira becoming drawn in to Stanley's extraordinary testimony, revealing new information about this highly specialised milieu of textile production which is her particular interest. It was a true meeting of minds, and I stood by to observe the accumulation of mutual interest, as with growing delight Moira and Stanley exchanged anecdotes about their shared passion.

Recently, Stanley visited the Natural History Museum to hold the bones of his ancestor Jean the Sexton which were removed there from Christ Church for study, and by seeing the designs at the Victoria & Albert Museum that once passed before Jean's eyes in Spitalfields, he had completed his quest.

'It was a big day,' Stanley admitted to me afterwards, his eyes shining with emotion, as he began to absorb the reality of what he had seen.

Stanley Rondeau sees the design commissioned by his ancestor in the seventeen-forties for the first time

Design for a vellure for Jean Rondeau, by Anna Maria Garthwaite, Spitalfields, February 5th, 1741

The full page with Jean Rondeau's design at the top

Design for a damask by Anna Maria Garthwaite for Jean Rondeau, possibly for half-mourning

Stanley Rondeau chats with Moira Thunder, Curator, Designs, at the Victoria & Albert Museum, over a copy of Natalie Rothstein's definitive work "Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century."

Anna Maria Garthwaite's catalogue of designs

Designs by Anna Maria Garthwaite for Spitalfields silks from the seventeen forties in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Textile design photographs by Jane Petrie

Textiles copyright © Victoria & Albert Museum

With grateful thanks to Moira Thunder of the Victoria & Albert Museum for making this possible.

You may also like to read about

Stanley Rondeau died on 13th January aged ninety-two. His funeral will be on Wednesday 25th February at Edmonton Cemetery, 11.30am

Stanley Rondeau (1933-2026)

If you visited Nicholas Hawksmoor's Christ Church, Spitalfields on any given Tuesday, you would find Stanley Rondeau - where he volunteered one day each week - welcoming visitors and handing out guide books. The architecture is of such magnificence, arresting your attention, that you might not even have noticed this quietly spoken white-haired gentleman sitting behind a small table just to the right of the entrance, who came here weekly on the train from Enfield.

But if you were interested in local history, then Stanley was one of the most remarkable people you could hope to meet, because his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Jean Rondeau was a Huguenot immigrant who came to Spitalfields in 1685.

"When visiting a friend in Suffolk in 1980, I was introduced to the local vicar who became curious about my name and asked me 'Are you a Huguenot?'" explained Stanley with a quizzical grin. "I didn't even know what he meant," he added, revealing the origin of his life-changing discovery, "So I went to Workers' Educational Association evening classes in Genealogy and that was how it started. I've been at it now for thirty years. My own family history came first, but when I learnt that Jean Rondeau's son John Rondeau was Sexton of Christ Church, I got involved in Spitalfields. And now I come every Tuesday as a volunteer and I like being here in the same building where he was. They refer to me as 'a piece of living history', which is what I am really. Although I have never lived here, I feel I am so much part of the area."

Jean Rondeau was a serge weaver born in 1666 in Paris into a family that had been involved in weaving for three generations. Escaping persecution for his Protestant faith, he came to London and settled in Brick Lane, fathering twelve children. Jean had such success as weaver in London that in 1723 he built a fine house, number four Wilkes St, in the style that remains familiar to this day in Spitalfields. It is a indicator of Jean's integration into British society that his name is to be discovered on a document of 1728 ensuring the building of Christ Church, alongside that of Edward Peck who laid the foundation stone. Peck is commemorated today by the elaborate marble monument next to the altar, where I took Stanley's portrait which you can see above.

Jean's son John Rondeau was a master silk weaver and in 1741 he commissioned textile designs from Anna Maria Garthwaite, the famous designer of Spitalfields silks, who lived at the corner of Princelet St adjoining Wilkes St. As a measure of John's status, in 1745 he sent forty-seven of his employees to join the fight against Bonnie Prince Charlie. Appointed Sexton of the church in 1761 until his death in 1790, when he was buried in the crypt in a lead coffin labelled John Rondeau, Sexton of this Parish, his remains were exhumed at the end of twentieth century and transported to the Natural History Museum for study.

"Once I found that the crypt was cleared, I made an appointment at the Natural History Museum, where Dr Molleson showed his bones to me," admitted Stanley, widening his eyes in wonder. "She told me he was eighty-five, a big fellow - a bit on the chubby side, yet with no curvature of the spine, which meant he stood upright. It was strange to be able to hold his bones, because I know so much about his history," Stanley told me in a whisper of amazement, as we sat together, alone in the vast empty church that would have been equally familiar to John the Sexton.

In 1936, a carpenter removing a window sill from an old warehouse in Cutler St that was being refurbished was surprised when a scrap of paper fell out. When unfolded, this long strip was revealed to be a ballad in support of the weavers, demanding an Act of Parliament to prevent the cheap imports that were destroying their industry. It was written by James Rondeau, the grandson of John the Sexton who was recorded in directories as doing business in Cutler St between 1809 and 1816. Bringing us two generations closer to the present day, James Rondeau author of the ballad was Stanley's great-great-great-grandfather. It was three generations later, in 1882, that Stanley's grandfather left Sclater St and the East End for good, moving to Edmonton when the railway opened. And subsequently Stanley grew up without any knowledge of Huguenots or the Spitalfields connection, until that chance meeting in 1980 leading to the discovery that he was an eighth generation British Huguenot.

"When I retired, it gave me a new purpose," said Stanley, cradling the slender pamphlet he has written entitled The Rondeaus of Spitalfields. "It's a story that must not be forgotten because we were the originals, the first wave of immigrants that came to Spitalfields," he declared. Turning the pages slowly, as he contemplated the sense of connection that the discovery of his ancestry has given him, he admitted, "It has made a big difference to my life, and when I walk around in Christ Church today I can imagine my ancestor John the Sexton walking about in here, and his father Jean who built the house in Wilkes St. I can see the same things he did, and when I am able to hear the great eighteenth century organ, once it is restored, I can know that my ancestor played it and heard the same sound."

There is no such thing as an old family, just those whose histories are recorded. We all have ancestors - although few of us know who they were, or have undertaken the years of research Stanley Rondeau had done, bringing him into such vivid relationship with his ancestors. It granted him an enviably broad sense of perspective, seeing himself against a wider timescale than his own life. History became personal for Stanley Rondeau in Spitalfields.

The silk design at the top was commissioned from Anna Maria Garthwaite by Stanley's ancestor, Jean Rondeau, in 1742. (courtesy of V&A)

4 Wilkes St built by Jean Rondeau in 1723. Pictured here seen from Puma Court in the nineteen twenties, it was destroyed by a bomb in World War II and is today the site of Suskin's Textiles.

The copy of James Rondeau's song discovered under a window sill in Cutler St in 1936.

Stanley Rondeau standing in the churchyard near his home in Enfield, at the foot of the grave of John the Sexton's son and grandson (the author of the song) both called James Rondeau, and who coincidentally also settled in Enfield.

Walter Donohue by Sarah Ainslie

We are delighted to announce that - due to popular demand - script editor, producer and luminary of the British cinema, Walter Donohue has agreed to teach another two-day screenwriting course at Townhouse in Spitalfields on the weekend of 18th and 19th April.

Here are some comments by students on Walter's previous course:

"I just want to say thank you for putting on such a fantastic weekend - it was so, so interesting speaking with like-minded people who share such a love for film and to be able to speak to the wonderful Walter and Mike Figgis and glean some of their vast knowledge. The food was delicious and the setting was ideal, I really appreciate the effort that you put into making it such a fantastic weekend." MN

"The course itself exceeded my expectations - I learned so many invaluable lessons about screenwriting and the film industry itself. I will take all the new skills into my career. Both Mike Figgis and Walter led an incredibly useful course and truly took their time with each student." GE

"The weekend spent in the Townhouse was nothing short of wondrous. Walter's passion for writing and storytelling is infectious. For every story that the students had, Walter had suggestions that took that story to a new level. The man's knowledge of what is needed in screenwriting and how to pitch, for me, was invaluable. The weekend was two days that I will never forget. I now have the tools and ammunition to start my own personal project. The visit by Mike Figgis was insightful. His views on Hollywood and filmmaking were blunt, informative and most importantly, honest! I could have listened to him talk all day." JL

WALTER'S EXPERIENCE

In the eighties, Walter began working as a script editor, starting with Wim Wenders' Paris, Texas and Sally Potter's Orlando. Since then he has worked with some major filmmakers including Joel & Ethan Coen, Wim Wenders, Sally Potter, David Byrne, Mike Figgis, John Boorman, Viggo Mortensen, Alex Garland, Kevin Macdonald, and László Nemes.

For the past thirty years he has been editor of the Faber & Faber film list, publishing Pulp Fiction and Barbie, and screenplays by Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, David Lynch, Sally Potter, and Greta Gerwig & Noah Baumbach, Joel & Ethan Coen, and Christopher Nolan among many others.

Walter also published Scorsese on Scorsese, and edited the series of interview books with David Lynch, Robert Altman, Tim Burton, John Cassavetes, Pedro Almodovar and Christopher Nolan.

THE COURSE

Walter's course is suitable for all levels of experience from those who are complete beginners to those who have already written screenplays and seek to refresh their practise. The course is limited to sixteen students.

APPROACHES TO SCREENWRITING

Walter says -

"My course is about approaches to writing a screenplay rather than a literal step-by-step technique on how to write.

The objective of my course is to immerse participants in the world of film, acquainting them with a cinematic language which will enable them to create films that are unique and personal to themselves.

There are four approaches - each centred around a particular film which will be the focus of each of the four sessions.

The approaches are -

Structure: Paris, Texas

Viewpoint: Silence of the Lambs

Genre: Anora

Endings: Chinatown

Participants will be required to have seen all four films in advance of the course."

This is a unique opportunity to enjoy a convivial weekend with Walter in an eighteenth century townhouse in Spitalfields and learn how to approach your screenplay.

Refreshments, freshly baked cakes and lunches are included in the course fee of £350.

Please email spitalfieldslife@gmail.com to book your place.

Please note we do not give refunds if you are unable to attend or if the course is postponed for reasons beyond our control.

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

Cabaret producer and stripper, Lara Clifton, interviewed Maedb Joy, a poet and former sex worker of extraordinary moral courage who has created Sexquisite, a cabaret of performers with lived experience of sex work.

Portrait of Maedb Joy by Sarah Ainslie

Maedb Joy is a woman in her twenties who is on a mission to resist the simultaneous silencing of sex workers and appropriation of their culture. At Bethnal Green Working Men's Club, as part of the campaign against the threat of closure, I attended what was potentially one of the last events, Sexquisite, a sex-worker-run cabaret. It was the best audience I had stood amongst for a long time. The crowd was mixed in age, class, bodies and genders, giddy with the pleasure of being in a sex-positive, shame-free, celebratory space.

Fifteen years ago, I was interviewed by Spitalfields Life about my work as a stripper. At that time, there were few public spaces where sex workers could speak with nuance, pride and political clarity. What strikes me most is not how much has changed but how much organising, creativity and solidarity it still takes to claim space.

So when The Gentle Author invited me to interview Maedb, founder of Sexquisite, I was chuffed and this is her story, in her own words.

"I worked in the sex industry from when I was fourteen. I was very isolated and working in secret. The only other sex worker I knew I met on Tumblr. I didn't tell my friends.

When I was sixteen, I was arrested for working underage and was on bail for two years. It was a formative experience and really awful - I was forced to come out to my family. My dad was in police meetings with me, seeing everything. It destroyed our relationship.

That same year I had a road accident where I almost lost my right foot. But it ended up being a blessing because I started writing while I was in hospital. At first, I rewrote poems I found online, pretending they were my own. I was desperate for approval. Then I started writing about what had happened to me.

My mum, who is a feminist and an ex-music-journalist, started arranging gigs for me. They were punk gigs. I'd be the only teenager on a line-up with feminist punk bands, performing angry poetry about sex work.

After the accident, I went back to college and studied performing arts because I'd left school without GCSEs. We had to create a play and there wasn't room for another main character, so I wrote a monologue about a girl in a hostel who'd been groomed. That was the first time I told a couple of hundred people about what had happened to me, but I was playing a character. That's how I started performing, to talk about experiences without naming myself.

I got into Guildhall School of Music & Drama. In the second year, we had to put on an event. The event I put on was Sexquisite. That was the beginning of 2019.

At that point, I had no sex worker friends. People told me not to say anything about my past, that this was a fresh start. I was really scared. I was making art about my life but no one knew it was my own story. I didn't even know what cabaret was. I put out a call asking for multidisciplinary artists who were sex workers - poetry, comedy, burlesque, theatre. Through Sexquisite I started meeting people like me.

Being a sex worker is very marginalising. People don't understand what it's like, having family angry at you, friends who won't speak to you, partners who call you a whore. Performance was how I could show the complexity of it. Through a monologue you can explain what it actually feels like.

People think stigma is disappearing but I don't think it is. In sex-positive scenes - such as at the Bethnal Green Working Men's Social Club - it feels easier, but outside that bubble it's still dangerous. I know sex workers who have had their children taken away. People can't rent homes. They can't explain gaps in their CVs. Even legal work like web-camming is treated as immoral earnings.

Sex worker is the only marginalised identity people believe you choose. That alone says a lot. You're never allowed to say you had a bad day at work, people tell you you shouldn't be doing it at all. Even within families it becomes a source of shame. This is why the law matters. The Online Safety Act has been coming into force this year and it's had huge consequences. Platforms are deleting adult content, closing accounts, wiping out years of work overnight. Websites face massive fines if they don't comply, so many are just cutting off adult material entirely.

It's sold as protection but it's collecting people's data, pushing sex workers off safer platforms and into more dangerous situations. It's also erased support spaces such as forums, harm-reduction networks and community archives. That's not accidental. There are also ongoing attempts to expand criminalisation through policing and crime bills and to push versions of the Nordic Model, which claims to protect workers but actually makes screening clients harder and working conditions less safe. These laws don't remove sex work, they remove safety for sex workers.

Meanwhile there's a weird contradiction happening culturally. Sex worker aesthetics are everywhere. Some people dress like strippers, use the language and take the imagery, but they don't work shifts or deal with the consequences, or support the sex worker community. At the same time, actual sex workers are being de-platformed and legislated against. That contradiction is exhausting but it's also why my work has to keep going.

I want to start a UK Sex Worker Pride, in the same way we have Trans Pride and Black Pride. It'll take maybe a team of a hundred people. I would love to do a big march and a big party. This year I'm doing a programme of events but next year it would be cool to make it bigger."

Maedb performing one of her poems at Bethnal Green Working Men's Social Club

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

On Valentine's Day, I cannot help thinking back to the days when we had Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green to make the East End a more colourful place, before she was 'socially cleansed' to Uttoxeter

Viscountess Boudica of Bethnal Green confessed to me that she never received a Valentine in her entire life and yet, in spite of this unfortunate example of the random injustice of existence, her faith in the future remained undiminished.

Taking a break from her busy filming schedule, the Viscountess granted me a brief audience to reveal her intimate thoughts upon the most romantic day of the year and permit me to take these rare photographs that reveal a candid glimpse into the private life of one of the East End's most fascinating characters.

For the first time since 1986, Viscountess Boudica dug out her Valentine paraphernalia of paper hearts, banners, fairylights, candles and other pink stuff to put on this show as an encouragement to the readers of Spitalfields Life. "If there's someone that you like," she says, "I want you to send them a card to show them that you care."

Yet behind the brave public face, lay a personal tale of sadness for the Viscountess. "I think Valentine's Day is a good idea, but it's a kind of death when you walk around the town and see the guys with their bunches of flowers, choosing their chocolates and cards, and you think, 'It should have been me!'" she admitted with a frown, "I used to get this funny feeling inside, that feeling when you want to get hold of someone and give them a cuddle."

Like those love-lorn troubadours of yore, Viscountess Boudica mined her unrequited loves as a source of inspiration for her creativity, writing stories, drawing pictures and - most importantly - designing her remarkable outfits that record the progress of her amours. "There is a tinge of sadness after all these years," she revealed to me, surveying her Valentine's Day decorations," but I am inspired to believe there is still hope of domestic happiness."

Take a look at

The Departure of Viscountess Boudica

Viscountess Boudica's Domestic Appliances

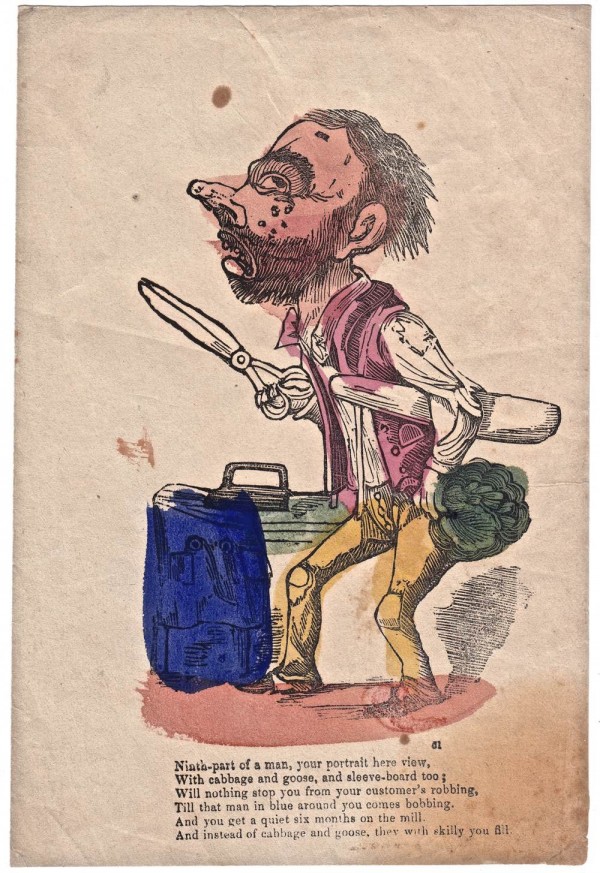

Inveterate collector, Mike Henbrey acquired harshly-comic nineteenth century Valentines for more than twenty years and his collection is now preserved in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute.

Mischievously exploiting the anticipation of recipients on St Valentine's Day, these grotesque insults couched in humorous style were sent to enemies and unwanted suitors, and to bad tradesmen by workmates and dissatisfied customers. Unsurprisingly, very few have survived which makes them incredibly rare and renders Mike's collection all the more astonishing.

"I like them because they are nasty," Mike admitted to me with a wicked grin, relishing the vigorous often surreal imagination at work in his cherished collection - of which a small selection are published here today - revealing a strange sub-culture of the Victorian age.

.

Images courtesy Mike Henbrey Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

You might also like to look at

John the Fox, 1978

Half a century ago, documentary photographer Joyce Edwards (1925-2024) took these tender portraits of the squatters who inhabited empty houses in the triangle of streets next to Victoria Park which had been vacated for the sake of a proposed inner city motorway that was never built. Her pictures are now being shown publicly for the first time at Four Corners in Bethnal Green in an exhibition entitled, Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters, which opens tomorrow and runs until Saturday 20th March.

Joyce Edwards, 1980

Harold the Kangaroo, painter, with his dog Captain Beefheart, 1978

Billy Cowden, Joy Rigard & Jamie, 1978

Henry Woolf, actor, 1974

Beverly Spacie, 1977

Anthony & Andrew Minion, 1980

Elizabeth Shepherd, actor, c. 1970

John, painter,1979

Gary Chamberlin, Beverly Spacie & Howard Dillon, 1977

Julia Clement, 1978

Vanessa Swann & Baz O' Connell, 1979

Matthew Simmons, 1978

Shirley Robbins, 1977

Tosh Parker, 1977

Sue, 1977

Father & son, 1976

103 Bishops Way E2, Co-op headquarters, 1978

Attempted eviction, 1978

Joyce Edwards, 2012

Photographs copyright © Estate of Joyce Edwards

Joyce Edwards: A Story Of Squatters is at Four Corners, 121 Roman Rd, E2 0QN. Friday 13th February until Saturday 20th March (Wednesday to Saturday, 11am - 6pm)

You may also like to take a look at

As any accountant will tell you - you must always keep your receipts. It was a dictum adopted religiously by the staff at London oldest ironmongers R. M. Presland & Sons in the Hackney Rd from 1797-2013, where this cache of receipts from the eighteen-eighties and nineties was discovered. They may no longer be of interest to the tax man, but they serve to illustrate the utilitarian beauty of nineteenth-century typographic design and tell us a lot about the diverse interrelated trades which once filled this particular corner of the East End.

You may also like to read about

Rope makers of Stepney

In Stepney, there has always been an answer to the question, "How long is a piece of string?" It is as long as the distance between St Dunstan's Church and Commercial Rd, which is the extent of the former Frost Brothers' Rope Factory.

Let me explain how I came upon this arcane piece of knowledge. First I published a series of photographs from a copy of Frost Brothers' Album in the archive of the Bishopsgate Institute produced around 1900, illustrating the process of rope making and yarn spinning. Then, a reader of Spitalfields Life walked into the Institute and donated a series of four group portraits of rope makers at Frost Brothers which I publish here.

I find these pictures even more interesting than the ones I first showed because, while the photos in the Album illustrate the work of the factory, in these newly-revealed photos the subject is the rope makers themselves.

There are two pairs of pictures. Photographed on the same day, the first pair taken - in my estimation - around 1900, show a gang of men looking rather proud of themselves. There is a clear hierarchy among them and, in the first photo, they brandish tankards suggesting some celebratory occasion. The men in bowler hats assume authority and allow themselves more swagger while those in caps withhold their emotions. Yet although all these men are deliberately presenting themselves to the camera, there is relaxed quality and swagger in these pictures which communicates a vivid sense of the personality and presence of the subjects.

The other two photographs show larger groups and I believe were taken as much as a decade earlier. I wonder if the tall man in the bowler hat with a moustache in the centre of the back row in the first of these is the same as the man in the bowler hat in the later photographs? In these earlier photographs, the subjects have been corralled for the camera and many regard us with a weary implacable gaze.

The last of the photographs is the most elaborately staged and detailed. It repays attention for the diverse variety of expressions among its subjects, ranging from blank incomprehension of some to the tenderness of the young couple with the young man's hands upon the young woman's shoulders - a fleeting gesture of tenderness recorded for eternity.

I was so fascinated by these photographs I wanted to go and find the rope works for myself and, on an old map, I discovered the ropery stretching from Commercial Rd to St Dunstan's, but - alas - I could discern nothing on the ground to indicate it was ever there. The Commercial Rd end of the factory is now occupied by the Tower Hamlets Car Pound, while the long extent of the ropery has been replaced by a terrace of house called Lighterman's Court that, in its length and extent, follows the pattern of the earlier building quite closely. At the northern end, there is now a park where the factory reached the road facing St Dunstan's. Yet the terraces of nineteenth century housing in Bromley St and Belgrave St remain on either side and, in Bromley St, the British Prince where the rope makers once quenched their thirsts still stands.

After the disappointment of my quest to find the rope works, I cherish these photographs of the rope makers of Stepney even more as the best record we have of their existence.

Gang of rope makers at Frost Brothers (You can click to enlarge this image)

Rope makers with a bale of fibre and reels of twine (You can click to enlarge this image )

Rope makers including women and boys with coils of rope (You can click to enlarge this image)

Frost Brothers Ropery stretched from Commercial St to St Dunstan's Churchyard in Stepney

In Bromley St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to read the original post

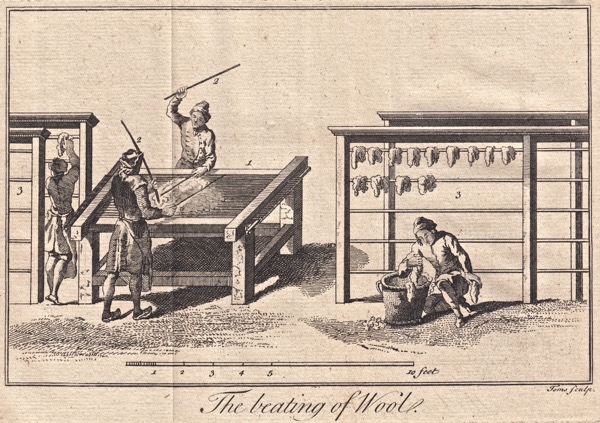

Founded by John James Frost in 1790, Frost Brothers Ltd of 340/342 Commercial Rd was managed by his grandson - also John James Frost - in 1905, when these photographs were taken. In 1926, the company was amalgamated to become part of British Ropes and now only this modest publication on the shelf in the Bishopsgate Institute bears testimony to the long-lost industry of rope making and yarn spinning in the East End, from which Cable St takes its name.

First Prize London Cart Parade - Manila Hemp as we receive it from the Philippines

Hand Dressing

The Old-Fashioned Method of Hand Spinning

The First Process in Spinning Manila - The women are shown feeding Hemp up to the spreading machines, taken from the bales as they come from the Philippines. These three machines are capable of manipulating one hundred and twenty bales a day.

Manila-Finishing Drawing Machines

Russian & Italian Hemp Preparing Room

Manila Spinning

Binder Twine & Trawl Twine Spinning - This floor contains one hundred and fifty six spindles

Russian & Italian Hemp Spinning

Carding Room

Tow Drawing Room

Tow Spinning & Spun Yarn Twisting Room

Tarred Yarn Store - This contains one hundred and fifty tons of Yarn

Tarred Yarn Winding Room

Upper End of Main Rope Ground - There are six ground four hundred yards long, capable of making eighteen tons of rope per ten and a half hour day

Rope-Making Machines - This pair of large machines are capable of making rope up to forty-eight centimetres in circumference

House Machines - This view shows part of the Upper Rope Ground and a couple of small Rope-Making Machines

Number 4 House Machine Room

The middle section of a machine capable of making rope from three inches up to seven inches in circumference, any length without a splice. It is thirty-two feet in height and driven by an electric motor.

Number 4 Rope Store

Boiler House

120 BHP. Sisson Engine Direct Coupled to Clarke-Chapman Dynamo

One of our Motors by Crompton 40 BHP - These Manila Ropes have been running eight years and are still in first class condition.

Engineers' Shop with Smiths' Shop adjoining

Carpenters' Store & Store for Spare Gear

Exhibit at Earl's Court Naval & Shipping Exhibition, 1905

View of the Factory before the Fire in 1860

View of the Factory as it is now in 1905 - extending from Commercial St

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Long-Song Seller

There is a silent ghost who accompanies me in my work, following me down the street and sitting discreetly in the corner while I am doing my interviews. He is always there in the back of my mind. He is Henry Mayhew, whose monumental work,"London Labour & London Poor," was the first to give ordinary people the chance to speak in their own words. I often think of him, and the ambition and quality of his work inspires me. And I sometimes wonder what it was like for him, pursuing his own interviews, one hundred and fifty years ago, in a very different world.

Mayhew's interviews and pen portraits appeared in the London Chronicle and were published in two volumes in 1851, eventually reaching their final form in five volumes published in 1865. In his preface, Mayhew described it as "the first attempt to publish the history of the people, from the lips of the people themselves - giving a literal description of their labour, their earnings, their trials and their sufferings in their own unvarnished language."

These works were produced before photography was widely used to illustrate books, and although photographer Richard Beard produced a set of portraits to accompany Mayhew's interviews, these were reproduced by engraving. Fortunately, since Beard's photographs have not survived, the engravings were skillfully done. And they are fascinating images, because they exist as the bridge between the popular prints of the Cries of London that had been produced for centuries and the development of street photography, initiated by JohnThomson's "Street Life in London" in 1876.

Primarily, Mayhew's intention was to create a documentary record, educating his middle class readers about the lives of the poor to encourage social change. Yet his work transcends the tragic politics of want and deprivation that he set out to address, because the human qualities of his subjects come alive on the page and command our respect. Henry Mayhew bears witness not only to the suffering of poor people in nineteenth century London, but also to their endless resourcefulness and courage in carving out lives for themselves in such unpromising circumstances.

The Oyster Stall. "I've been twenty years and more, perhaps twenty-four, selling shellfish in the streets. I was a boot closer when I was young, but I had an attack of rheumatic fever, and lost the use of my hands for my trade. The streets hadn't any great name, as far as I knew, then, but as I couldn't work, it was just a choice between street selling and starving, so I didn't prefer the last. It was reckoned degrading to go into the streets - but I couldn't help that. I was astonished at my success when I first began, I made three pounds the first week I knew my trade. I was giddy and extravagant. I don't clear three shillings a day now, I average fifteen shillings a week the year through. People can't spend money in shellfish when they haven't got any."

The Irish Street-Seller. "I was brought over here, sir, when I was a girl, but my father and mother died two or three years after. I was in service, I saved a little money and got married. My husband's a labourer, he's out of worruk now, and I'm forced to thry and sill a few oranges to keep a bit of life in us, and my husband minds the children. Bad as I do, I can do a penny or tuppence a day better profit than him, poor man! For he's tall and big, and people thinks, if he goes round with a few oranges, it's just from idleniss."

The Groundsel Man. "I sell chickweed and grunsell, and turfs for larks. That's all I sell, unless it's a few nettles that's ordered. I believe they're for tea, sir. I gets the chickweed at Chalk Farm. I pay nothing for it. I gets it out of the public fields. Every morning about seven I goes for it. I've been at business about eighteen year. I'm out till about five in the evening. I never stop to eat. I am walking ten hours every day - wet and dry. My leg and foot and all is quite dead. I goes with a stick."

The Baked Potato Man. "Such a day as this, sir, when the fog's like a cloud come down, people looks very shy at my taties. They've been more suspicious since the taty rot. I sell mostly to mechanics, I was a grocer's porter myself before I was a baked taty. Gentlemen does grumble though, and they've said, "Is that all for tuppence?" Some customers is very pleasant with me, and says I'm a blessing. They're women that's not reckoned the best in the world, but they pays me. I've trusted them sometimes, and I am paid mostly. Money goes one can't tell how, and 'specially if you drinks a drop as I do sometimes. Foggy weather drives me to it, I'm so worritted - that is, now and then, you'll mind, sir."

The London Coffee Stall. "I was a mason's labourer, a smith's labourer, a plasterer's labourer, or a bricklayer's labourer. I was for six months without any employment. I did not know which way to keep my wife and child. Many said they wouldn't do such a thing as keep a coffee stall, but I said I'd do anything to get a bit of bread honestly. Years ago, when I as a boy, I used to go out selling water-cresses, and apples, and oranges, and radishes with a barrow. I went to the tinman and paid him ten shillings and sixpence (the last of my savings, after I'd been four or five months out of work) for a can. I heard that an old man, who had been in the habit of standing at the entrance of one of the markets, had fell ill. So, what do I do, I goes and pops onto his pitch, and there I've done better than ever I did before."

Coster Boy & Girl Tossing the Pieman. To toss the pieman was a favourite pastime with costermonger's boys. If the pieman won the toss, he received a penny without giving a pie, if he lost he handed it over for nothing. "I've taken as much as two shillings and sixpence at tossing, which I shouldn't have done otherwise. Very few people buy without tossing, and boys in particular. Gentlemen 'out on the spree' at the late public houses will frequently toss when they don't want the pies, and when they win they will amuse themselves by throwing the pies at one another, or at me. Sometimes I have taken as much as half a crown and the people of whom I had the money has never eaten a pie."

The Street- Seller of Nutmeg Graters. "Persons looks at me a good bit when I go into a strange place. I do feel it very much, that I haven't the power to get my living or to do a thing for myself, but I never begged for nothing. I never thought those whom God had given the power to help themselves ought to help me. My trade is to sell brooms and brushes, and all kinds of cutlery and tinware. I learnt it myself. I was never brought up to nothing, because I couldn't use my hands. Mother was a cook in a nobleman's family when I was born. They say I was a love child. My mother used to allow so much a year for my schooling, and I can read and write pretty well. With a couple of pounds, I'd get a stock, and go into the country with a barrow, and buy old metal, and exchange tinware for old clothes, and with that, I'm almost sure I could make a decent living."

The Crockery & Glass Wares Street-Seller. "A good tea service we generally give for a left-off suit of clothes, hat and boots. We give a sugar basin for an old coat, and a rummer for a pair of old Wellington boots. For a glass milk jug, I should expect a waistcoat and trowsers, and they must be tidy ones too. There is always a market for old boots, when there is not for old clothes. I can sell a pair of old boots going along the streets if I carry them in my hand. Old beaver hats and waistcoats are worth little or nothing. Old silk hats, however, there's a tidy market for. There is one man who stands in Devonshire St, Bishopsgate waiting to buy the hats of us as we go into the market, and who purchases at least thirty a week. If I go out with a fifteen shilling basket of crockery, maybe after a tidy day's work I shall come home with a shilling in my pocket and a bundle of old clothes, consisting of two or three old shirts, a coat or two, a suit of left-off livery, a woman's gown maybe or a pair of old stays, a couple of pairs of Wellingtons, and waistcoat or so."

The Blind Bootlace Seller. "At five years old, while my mother was still alive, I caught the small pox. I only wish vaccination had been in vogue then as it is now or I shouldn't have lost my eyes. I didn't lose both my eyeballs till about twenty years after that, though my sight was gone for all but the shadow of daylight and bright colours. I could tell the daylight and I could see the light of the moon but never the shape of it. I never could see a star. I got to think that a roving life was a fine pleasant one. I didn't think the country was half so big and you couldn't credit the pleasure I got in going about it. I grew pleaseder and pleaseder with the life. You see, I never had no pleasure, and it seemed to me like a whole new world, to be able to get victuals without doing anything. On my way to Romford, I met a blind man who took me in partnership with him, and larnt me my business complete - and that's just about two or three and twenty year ago."

The Street Rhubarb & Spice Seller. "I am one native of Mogadore in Morocco. I am an Arab. I left my countree when I was sixteen or eighteen years of age, I forget, sir. Dere everything sheap, not what dey are here in England. Like good many, I was young and foolish - like all dee rest of young people, I like to see foreign countries. The people were Mahomedans in Mogadore, but we were Jews, just like here, you see. In my countree the governemen treat de Jews very badly, take all deir money. I get here, I tink, in 1811 when de tree shilling pieces first come out. I go to de play house, I see never such tings as I see here before I come. When I was a little shild, I hear talk in Mogadore of de people of my country sell de rhubarb in de streets of London, and make plenty money by it. All de rhubarb sellers was Jews. Now dey all gone dead, and dere only four of us now in England. Two of us live in Mary Axe, anoder live in, what dey call dat - Spitalfield, and de oder in Petticoat Lane. De one wat live in Spitalfield is an old man, I dare say going on for seventy, and I am little better than seventy-three."

The Street-Seller of Walking Sticks. "I've sold to all sorts of people, sir. I once had some very pretty sticks, very cheap, only tuppence a piece, and I sold a good many to boys. They bought them, I suppose, to look like men and daren't carry them home, for once I saw a boy I'd sold a stick to, break it and throw it away just before he knocked at the door of a respectable house one Sunday evening. There's only one stick man on the streets, as far as I know - and if there was another, I should be sure to know."

The Street Comb Seller. "I used to mind my mother's stall. She sold sweet snuff. I never had a father. Mother's been dead these - well, I don't know how long but it's a long time. I've lived by myself ever since and kept myself and I have half a room with another young woman who lives by making little boxes. She's no better off nor me. It's my bed and the other sticks is her'n. We 'gree well enough. No, I've never heard anything improper from young men. Boys has sometimes said when I've been selling sweets, "Don't look so hard at 'em, or they'll turn sour." I never minded such nonsense. I has very few amusements. I goes once or twice a month, or so, to the gallery at the Victoria Theatre, for I live near. It's beautiful there, O, it's really grand. I don't know what they call what's played because I can't read the bills. I'm a going to leave the streets. I have an aunt, a laundress, she taught me laundressing and I'm a good ironer. I'm not likely to get married and I don't want to."

The Grease-Removing Composition Sellers. "Here you have a composition to remove stains from silks, muslins, bombazeens, cords or tabarets of any kind or colour. It will never injure or fade the finest silk or satin, but restore it to its original colour. For grease on silks, rub the composition on dry, let it remain five minutes, then take a clothes brush and brush it off, and it will be found to have removed the stains. For grease in woollen cloths, spread the composition on the place with a piece of woollen cloth and cold water, when dry rub it off and it will remove the grease or stain. For pitch or tar, use hot water instead of cold, as that prevents the nap coming off the cloth. Here it is. Squares of grease removing composition, never known to fail, only a penny each."

The Street Seller of Birds' Nests. "I am a seller of birds'-nesties, snakes, slow-worms, adders, "effets" - lizards is their common name - hedgehogs (for killing black beetles), frogs (for the French - they eats 'em), and snails (for birds) - that's all I sell in the Summertime. In the Winter, I get all kinds of of wild flowers and roots, primroses, buttercups and daisies, and snowdrops, and "backing" off trees ("backing," it's called, because it's used to put at the back of nosegays, it's got off yew trees, and is the green yew fern). The birds' nests I get from a penny to threepence a piece for. I never have young birds, I can never sell 'em, you see the young things generally die of cramp before you can get rid of them. I gets most of my eggs from Witham and Chelmsford in Essex. I know more about them parts than anybody else, being used to go after moss for Mr Butler, of the herb shop in Covent Garden. I go out bird nesting three times a week. I'm away a day and two nights. I start between one or two in the morning and walk all night. Oftentimes, I wouldn't take 'em if it wasn't for the want of the victuals, it seems such a pity to disturb 'em after they made their little bits of places. Bats I never take myself - I can't get over 'em. If I has an order of bats, I buys 'em off boys."

The Street-Seller of Dogs. "There's one advantage in my trade, we always has to do with the principals. There's never a lady would let her favouritist maid choose her dog for her. Many of 'em, I know dotes on a nice spaniel. Yes, and I've known gentleman buy dogs for their misses. I might be sent on with them and if it was a two guinea dog or so, I was told never to give a hint of the price to the servant or anybody. I know why. It's easy for a gentleman that wants to please a lady, and not to lay out any great matter of tin, to say that what had really cost him two guineas, cost him twenty."

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to take a look at

John Thomson's Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee's New London Cries

Marcellus Laroon's Cries of London

More John Player's Cries of London

William Nicholson's London Types

Francis Wheatley's Cries of London

John Thomas Smith's Vagabondiana of 1817

Last month - courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute - I published the 1896 cycling accessories catalogue of the Metropolitan Machinists' Co of Bishopsgate Without and today I publish their catalogue from 1906 as an illustration of how rapidly cycling advanced into the new century, especially - as you will see - in the applied science of the 'Anatomical Saddle' which offered extra support to the ischial tuberosities.

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

The Metropolitan Machinists' Co, 1896

Four-hundred-year-old stone floor at The Prospect of Whitby

Tempted by the irresistible promise of the riverside, I set out for Wapping to visit those pubs which remain in these formerly notorious streets once riddled with ale houses. Yet although there are pitifully few left these days, I discovered each one has a different and intriguing story to tell.

Town of Ramsgate, 288 Wapping High St. The first alehouse was built on this site in 1460, known as The Hostel and then as The Red Cow from 1533. The pub changed its name again, to the Town of Ramsgate, in 1766 to attract trade from Kentish fishermen who unloaded their catch at Wapping Old Stairs adjoining. Judge Jeffreys was arrested here in disguise, attempting to follow the flight of James II abroad in 1688, as William III's troops approached London.

The Turk's Head, 1 Green Bank. Originally in Wapping High St from 1839, rebuilt on this site in 1927 and closed in the seventies, it is now a community cafe.

Captain Kidd, 108 Wapping High St. Established in 1991 in a former warehouse and named after legendary pirate, Wiiliam Kidd, hanged nearby at Execution Dock Stairs in 1701.

Turner's Old Star, 14 Watts St. In the eighteen-thirties, Joseph Mallord William Turner set up his mistress Sophia Booth in two cottages on this site, one of which she ran as an alehouse named The Old Star. In 1987, the current establishment was renamed Turner's Old Star in honour of the connection with the great painter. Notoriously secretive about his lovelife, Turner adopted Sophia's surname to conceal their life together here, acquiring the nickname 'Puggy Booth' on account of his portly physique and height of just five feet.

The Old Rose, 128 The Highway. 1839-2007

The last pub standing on the Ratcliffe Highway

The Three Suns, 61 Garnet St. 1851 - 1986

The Prospect of Whitby, 56 Wapping Wall. Founded 1520, and formerly known as The Pelican and The Devil's Tavern.

What does a cat have to do to get a drink around here?

Sir Hugh Willoughby sailed from The Prospect of Whitby in 1533 upon his ill-fated attempt to discover the North-East Passage to China.

The Grapes, 76 Narrow St. Founded in 1583, the current building was constructed in 1720 - it is claimed Charles Dickens danced upon the counter here as a child.

You may like to read about my other pub crawls

The Gentle Author's Next Pub Crawl

The Gentle Author's Spitalfields Pub Crawl

Photographer Patricia Niven and Novelist Sarah Winman made this series of portraits and interviews at the Surma Centre at Toynbee Hall.

"After the Second World War, Britain required labour to assist in post-war reconstruction. Commonwealth countries were targeted and, in what was then East Pakistan (it became Bangladesh after the 1971 Liberation War), vouchers appeared on Post Office counters, urging people to come and work in the United Kingdom, no visa required. The majority of men who came in the fifties and sixties came from a rural background where education was scarce and illiteracy was common. But this generation were hard workers, used to working with their hands, men who could commit to long hours, who had an eagerness to work and a young man's inquisitiveness to see the world: the perfect workforce to help rebuild this nation. And they did rebuild it, and were soon found working in factories and ship yards, building roads and houses, crossing seas in the merchant navy. These pioneers were the men we met at the Surma Centre." - Sarah Winman

Shah Mohammed Ali

I came to this country in November 1961 because my uncle was already living here and inspired me to come. In East Pakistan, I had been working in a shop. I felt life was good. My earliest memory of London was Buckingham Palace. I missed my friends and family but I really missed the weather back home. I became a factory worker, and worked all over the country: a cotton factory in Oldham, a foundry in Sheffield, an aluminium factory in London and Ford motor factory in Dagenham. Ford gave me a good, comfortable life. We had friends all over the country and they would tell us if there was more money being offered at a different factory and then we'd move. I thought I would stay in Britain for four years and then go back home. My heart is in Bangladesh. The roses smell sweeter.

Eyor Miah

I came to this country in September 1965. I had been a student in East Pakistan. Life was hard, my father was a sailor. I read in a Bengali newspaper stories of people travelling and earning money, and I thought that I, too, would like to do that. I wrote to somebody I knew here to help me. It was a slow process, all done by mail, because of course, there was no internet. It took me two years to gain my papers. I didn't mind because I was very determined to achieve.

When I first arrived, I became a machinist in the tailoring industry and I earned £1 and ten shillings a week. My weekly outlay was £1 and the rest I saved. Brick Lane was very rundown then. The Jewish population were very welcoming, probably because they were eager for workers! We would queue up outside the mosque and they would come and pick the ones they wanted. In 1969 I bought a house for £55. Of course, I missed my mother who stayed in Bangladesh, and before 1971 I actually thought I would return to live. After that date though, I felt Britain was my home and life was better here.

After tailoring, I worked in restaurants and then began my own business as a travel agent, set up my own restaurants and grocery shop. I have four children. Life has been good to me.

Rokib Ullah

I came to this country in 1959, because workers were being recruited from the Commonwealth to rebuild after the Second World War. Life in East Pakistan then was good. I was very young and working as a farmer. My fellow countrymen told me about the work in the UK and I came here by air. When I arrived, the airport was so small, not like it is today. And the weather was awful, so bad, not like home, I found that difficult, together with missing my neighbours and friends. I worked in a tyre factory, and then in garment and leather factories. I planned to stay here and earn enough money, and then return to Bangladesh. I am a pensioner now and frequently go back to Bangladesh. It is in my heart. One day I plan to go there forever.

Syed Abdul Kadir

I first came to this country in 1953. I was in the navy in Karachi and I was selected by the Pakistan Government to be in the Guard of Honour in London at the Queen's Coronation. I remember this day very clearly. It was June and the weather was cold. When Queen Elizabeth was crowned the noise was tremendous. There were shouts of "God Save the Queen!" and gun salutes were fired. We marched to Buckingham Palace where more crowds were waiting. The Queen and her family came out on the balcony and the RAF flew past the Mall, and the skies above Victoria Embankment were lit up by fireworks. I feel very lucky to have been part of this, and I still have my Coronation ceremony medal.

Since my first visit, I developed a fondness for the British culture, its people and the Royal Family. I have always believed this country looks after its poor.

I owe the Pakistan Navy for much of my experiences in life and was lucky to travel and to see the world. I actively participated in the 1965 India-Pakistan war and the 1971 Pakistan war and have medals for both.

My family are settled here and my life revolves around grandchildren. I have been coming to Surma since 2004. When someone sees me, they call me "Captain!" We are like a family here.

Shunu Miah

I came to this country in November 1961. Back home, I helped my father farm. It was a good life, still East Pakistan, the population was low, not much poverty, food for everyone: it was a land of plenty. It wasn't a bad life, I was young and was just looking for more. My uncle had been in the UK since 1931, my father since 1946, both encouraged me to come.

Cinema here was my greatest memory. Back home, cinema was rare. Every Saturday and Sunday there was a cinema above Cafe Naz on Brick Lane, or I'd go to the cinema in Commercial Rd, or up to the West End. It was so exciting, the buildings, the underground, the lights! People were friendly and welcoming then. I saw Indian films, but also Samson and Delilah and the Ten Commandments with Charlton Heston.

I have worked at the Savoy Hotel as a kitchen porter and also in cotton factories in Bradford. What did I miss? Family and friends, of course, but also the weather. The smell of flowers, too, they are much stronger back home. I thought I would stay here and work for three or four years, go home and buy land, build a house and live happily ever after. I have helped to build homes for my family in Bangladesh. I have never been able to own a home here.

Abul Azad, Co-ordinator at the Surma Centre.

"These men are very loyal to a country that has given them a home," said Abul Azad, the charismatic project co-ordinator at Surma Centre in Whitechapel. "When they first arrived, living conditions were bad, sometimes up to ten people lived in a room. Facilities were unhealthy, toilets outside, and nothing to protect them from an unfamiliar cold that many still talk about. Most intended to earn money to send back to families, and then return after a few years - a dream realised by few, especially after the settlement of families. Instead they were open to exploitation, often working over sixty hours a week, the consequence of which is clearly visible today in low state pensions, due to companies not paying the correct National Insurance contributions. And most Bangladeshi people don't have private pensions. Culturally, pensions are not of this generation. Their families are their pension - always imagined they would be looked after. But times are changing for everyone."

Surma runs a regular coffee morning, providing support for elderly Bangladeshi people. The language barrier is still the greatest hindrance to this older generation and Surma provides a specialist team ready to assist their needs - both financially and socially - and to provide free legal advice. It is also quite simply a haven for people to get out of the house and to be amongst their peers, to read newspapers, to have discussions, to talk about what is happening here and in Bangladesh.

There is something profound that holds this group together, a deep unspoken, clothed in dignity. Maybe it is the history of a shared journey, where the desire for a better life meant hours of physical hardship and unceasing toil and lonely years of not being able to communicate. Maybe it is quite simply the longing for home, remaining just that: an unrealised dream. Whatever it is - "This is a very beautiful group." said Abul Azad.

Photographs copyright © Patricia Niven

You may also like to take look at these other portraits by Patricia Niven and Sarah Winman

After more than a century of operation, Nelson St Synagogue is to be auctioned off on 12th February. Since part of the roof collapsed at the time of the pandemic in 2020 it has been disused. Click here for details of the auction

Below you can read my account of a visit there in 2012.

Leon Silver

When Leon Silver opened the golden shutter of the ark at the East London Central Synagogue in Nelson St for me, a stash of Torah scrolls were revealed shrouded in ancient velvet with embroidered texts in silver thread gleaming through the gloom, caught by last rays of afternoon sunlight.

Leon told me that no-one any longer knows the origin of all these scrolls, which were acquired as synagogues closed or amalgamated with the departure of Jewish people from the East End since World War II. Many scrolls were brought over in the nineteenth century from all across Eastern Europe, and some are of the eighteenth century or earlier, originating from communities that no longer exist and places that vanished from the map generations ago.

Yet the scrolls were safe in Nelson St under the remarkable stewardship of Leon Silver, President, Senior Warden & Treasurer, who had selflessly devoted himself to keeping this beautiful synagogue open for the small yet devoted congregation - mostly in their eighties and nineties - for whom it fulfilled a vital function. An earlier world still glimmered there in this beautiful synagogue that may not have seen a coat of new paint in a while, but was well tended by Leon and kept perfectly clean with freshly hoovered carpet and polished wood by a diligent cleaner of ninety years old.

As the sunlight faded, Leon and I sat at the long table at the back of the lofty synagogue where refreshments were enjoyed after the service, and Leon's cool grey eyes sparkled as he spoke of this synagogue that meant so much to him, and of its place in the lives of his congregation.

"I grew up in the East End, in Albert Gardens, half a mile from here. I first came to the synagogue as a little boy of four years old and I've been coming here all my life. Three generations of my family have been involved here, my maternal grandfather was the vice-president and my late uncle's mother's brother was the last president, he was still taking sacrament at ninety-five. My father used to come here to every service in the days when it was twice daily. And when I was twenty-nine, I came here to recite the mourner's prayer after my father died. I remember when it was so crowded on the Sabbath, we had to put benches in front of the bimmah to accommodate everyone, now it is a much smaller congregation but we always get the ten you need to hold a service.

I'm a professional actor, so it gives me plenty of free time. I was asked to be the Honorary Treasurer and told that it entailed no responsibility - which was entirely untrue - and I've done it ever since. As people have died or moved away, I have taken on more responsibility. It means a lot to me. There was talk of closing us down or moving to smaller premises, but I've fought battles and we are still here. I spend quite a lot of hours at the end of the week. We have refreshments after the service, cake, crisps and whisky. I do the shopping and put out the drinks. The majority here are quite elderly and they are very friendly, everyone gets on well, especially when they have had a few drinks. In the main, they are East Enders. We don't ask how they come because strictly speaking you shouldn't ride the bus on the Sabbath. Now, even if young Jewish people wanted to come to return to the East End there are no facilities for them. No kosher butcher or baker, just the kosher counter at Sainsburys.

My father's family came here at the end of the nineteenth century, and my maternal grandfather Lewis (who I'm named after) came at the outbreak of the First World War. As a resident alien, he had to report to Leman St Police Station every day. He came from part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and he came on an Austrian passport, but when my mother came in 1920, she came on a Polish passport. Then in 1940, my grandfather and his brothers were arrested and my grandmother was put in Holloway Prison, before they were all interned on the Isle of Man. Then my uncle joined the British army and was told on his way to the camp that his parents had been released. My grandparents' families on both sides died in the Holocaust. My mother once tried to write a list of all the names but she gave up after fifty because it was too upsetting. And this story is true for most of the congregation at the synagogue. One man of ninety from Alsace, he won't talk about it. A lot of them won't talk about it. These people carry a lot of history and that's why it's important for them to come together.

When Jewish people first came here, they took comfort from being with their compatriots who spoke the same style of Yiddish, the same style of pronunciation, the same style of worship. It was their security in a strange new world, a self-help society to help with unemployment and funeral expenses."

Thanks to Leon, the shul to existed as a sacred meeting place for these first generation immigrants - then in their senior years - who shared a common need to be among others with comparable experiences. Polite and softly spoken yet resolute in his purpose, Leon Silver was custodian of a synagogue that was a secure home for ancient scrolls and a safe harbour for those whose lives were shaped by their shared histories.

Photographs 2 & 3 © Mike Tsang

"I remember coming out of the tube in Whitechapel in 1974 and being overwhelmed," recalled Stephen Watts affectionately, his deep brown eyes glowing with inner fire to describe the spiritual epiphany of his arrival in the East End, when coming to London after three years on North Uist in the Outer Hebrides. Today Stephen lives in Shadwell and has a tiny writing office in the Toynbee Hall in Commercial St where I paid him a call upon him.

"Migration is in my awareness and in my blood," he admitted, referring to his family who were mountain people dwelling in the Swiss Alps on the Italian border - living twelve hundred feet above sea level - and his grandfather who came to London before the First World War, worked in a cafe in Soho and then bought his own cafe. "I realised this was an area of migration since the seventeenth century when the farm workers of Cambridgeshire, Kent and Suffolk began to arrive here, and I immediately felt an affinity for the place," Stephen continued, casting his thoughts back far beyond his own arrival in Whitechapel, yet wary to qualify the vision too, lest I should think it self-dramatising.

"It is very easy to be romantic about it, but I think migration has been the objective reality for many people in the twentieth and twenty-first century. So it seemed to be something very natural, when I came to live in Whitechapel." he revealed with an amiable smile. Yet although he allowed himself a moment to savour this thought, Stephen possesses a restless energy and a mind in constant motion, suggesting that he might be gone at any moment, and entirely precluding any sense of being at home and here to stay. Even if he has lived in his council house in Shadwell for forty years, I would not be surprised if the wind blew Stephen away.

A tall skinny man with his loose clothes hanging off him and his long white locks drifting around, Stephen does present a superficial air of insubstantiality, even other-wordliness. Yet when you are in conversation with Stephen you quickly encounter the substance of his quicksilver mind, moving swiftly and using words with delicate precision, making unexpected connections. "In the Outer Hebrides the unemployment rate was twenty-five per cent and it was the same in Tower Hamlets when I arrived," he said, informing me of the parallels with precise logic, "also Tower Hamlets had large areas of empty water then, just like the North Uist." drawing comparison between the abandoned dockland and the Hebridean sea lochs, in regions of Britain that could not be more different in ever other respect.

We took the advantage of the frosty sunlight to make a half hour's circuit of the streets attending Brick Lane and these familiar paths took on another quality in Stephen's company, because while I tend to be always going somewhere, Stephen has the sense to halt and look around - indicative of certain open-ness of temperament that has led him befriend all kinds of people in pubs and on the street in Whitechapel over the years. I took this moment to ask Stephen if he chose to be a poet. "I made a choice when I quit university after a year and went to live in North Uist," he said as we resumed our pace, "and then I made a choice to be a poet. But as a choice it was unavoidable, because I realised that it was so much part of me that not to have done it would be a denial of my humanity."

Returning to the Toynbee Hall, Stephen allowed me the privilege of a peek into his tiny room on an upper floor, not much larger than a broom cupboard. The walls were lined with thin poetry books in magnificent order, arrayed in wine boxes stacked floor to ceiling and standing proud of the walls to create bays, leaving space only for one as slim as Stephen to squeeze through. It was a sacred space, the lair of the mountain man or a hermit's retreat. It felt organic, like a cave, or maybe - it occurred to me - a shepherd's hut carved out of the rock. And there, up above Stephen's head was an old black and white photo of shepherds on a mountain road, taken in the Swiss Alps whence Stephen's family originate and where even now he still returns to visit his relatives.