When rock'n'roll began it certainly didn't seem like album music either, it was dance music driven by singular hits, and it needed to come up with a way to make albums work as albums, a way to piece them together as wholes rather than just containing a few hits and a lot of fillers. And eventually this got worked out, the "fillers" evolved from fast attempts to reinvoke the hit formula over and over, to an open space for trying out a variety of different types of stuff, without necessarily trying to make hits. Not that it always worked, but there never really seemed to be a constant question of "how to translate rock music into album music" - the solution just sort of developed by itself and now appears to be an intuitive understanding. If you're setting out to make a rock album, a bunch of songs of different kinds, and it doesn't work, it's not because you haven't squared the album circle, it's simply because your material isn't good enough. With rave music - well, with the whole post acid electronic scene, really - that never got to be the case. It wasn't just a matter of making good stuff, you also had to make a proper album context for it.

So why didn't rave music find a way to turn into album music, if it wasn't simply because it was too ecstatic, too lost-in-the-here-and-now-of-the-dancefloor-experience, to make sense outside of that context? I think there's several reasons: First of all, and unlike rock, "electronic dance music" never really lost its identity as "dance" music - which is why I'm using that rather clunky name for it, rather than simply calling it "rave" or "techno", both of which have much more specific meanings for a lot people. This is something that the older generation of rock critics embraced wholeheartedly, because it meant that they could dismiss it as mere faddish functionality - not something you'd really need to pay attention to, let alone try to understand on a deeper level, because it didn't have a deeper level, it was just about stupid fun on the dancefloor and nothing more. And sadly, a lot of rave insiders fully accepted this traditional, rock derived idea of musical substance (authenticity, narrative), and took it as a badge of honour that rave didn't contain any of that. Rather than figuring out how to understand and describe the music on its own terms, the easy option was to stay in the reservation and just use it as a defence: Yeah, you old farts don't understand it because you have to experience it in the context of the dancefloor and the lights and bass and the drugs, to get it - it can't work on its own, so of course it doesn't sound good at home. As if there wasn't plenty of people who did listen to it at home, or got it fine without the drugs'n'dancefloor-context (I'm one of them, and I've got several friends for whom it worked just as well).

That one of the most common umbrella terms for everything from deep house to eurodance to hardcore techno is simply "dance music", is exactly the problem - suggesting not just that it's music that can be used for dancing (unlike rock or jazz or hip hop?), but rather that it's the only use, that listening to it is pointless. This leads directly to the second reason that rave never fully managed to turn into album music, namely the split between electronic "dance music" and electronic "listening music". The "electronic listening music" was seen as the obvious way to approach the album market, because albums are, after all, something you "listen to". As a result, far too much of this stuff deliberately avoided everything that had made rave music so great - the brutally inhuman machine structures, the raw synthetic sounds, the harsh viscerality - in favour of a polished and pleasing mood music that too often came of strangely regressive compared to the dancefloor-stuff. I remember that the whole "ambient"-movement seemed inexplicable and disappointing to me at the time - not because I didn't like ambient, but exactly because I already knew it well: Ambient was an old style by the nineties, and it appeared to me such a ridiculously regressive move to go back to that just when something as radically new and exciting as rave and techno was happening, I couldn't understand why anyone from the electronic scene would rather look back just when electronic music was at its most revolutionary peak ever, let alone how they could claim that something as safe and well-established as ambient was a new front line.

Not that the ambient/"electronic listening music" camp didn't produce some really good stuff, they certainly delivered their share of the brilliant and incredibly inventive music that made the first half of the nineties such a golden age, but there was also a huge amount of it that sounded as tame and regressive as you'd expect from a movement that used a return to decades old contemplative mood music as the "mature" and "sophisticated" response to the not-just-music of the kids. Most of all, though, both parts suffered from this divide, as it meant that almost everything was forced into one of the two options, and the synthesis needed to make it work as versatile album music never really materialized - the "listening" albums all too often ended up as far too long "mind journeys", lacking the straightforward buzz and urgency of rave, while the pure rave albums either became collections of hits+fillers, trying to repeat a successful formula over a whole album, or tried to create variation through awful "rave ballads" or annoying guest vocalists.

The need for variation was worsened by the third obstacle for rave as album music: That rave just happened to break through at a time where everybody thought that the CD had won over vinyl, especially as the album format of the future. Even though rave and techno probably were the most resilient vinyl strongholds of the nineties, they still subscribed to the logic of vinyl = singles and CDs = albums. The consequence was that far too many electronic albums from this time were simply too long for their own good - the 74 available minutes of the CD became a standard that you were expected to fill out, whether you had the material or inspiration for it - there were even buyers who felt "cheated" if they didn't get their "money's worth" (apparently it was of less importance if the music was any good, as long as they got more of it). As a result of the 74 minutes as the default album length, just making a collection of straightforward rave tracks became a much more problematic option.

The pioneering "album rock" of the sixties had the great advantage that no one expected it to exceed forty minutes (and even thirty minutes or less was perfectly acceptable and far from unusual), which meant that even relatively single-minded rock or pop albums rarely dragged on for too long and became monotonous. It's hard to imagine that most classic rock albums would have gained much by being twice as long - even if the hypothetical extra material was as good as the original stuff, it seems likely that the end result would eventually become to samey. The sharp and precise format of the classic rock LP simply meant that even more-or-less one trick ponies could get away with presenting a handful of slightly different variations of the one trick. In the CD age that approach became increasingly problematic, and releasing an album started to be seen more and more as some sort of "project", something that had to show ambition, versatility and the ability to envision - as well as fill - a vast canvas. Which is all in all not the most obvious way to go when doing a "rave" album.

One solution to this problem was focusing on EPs for straightforward rave/techno/hardcore-releases. Rather than having to live up to the expectations of "the album", you could simply do 4-6 tracks that were good enough to stand on their own, yet with sufficient variation and ideas among them for the record to work as a whole. Effectively hijacking 12" singles and turning them into the rave scenes equivalent of the "classic", "handful of songs" rock album, the early nineties was a golden age for the EP format. As for actual albums, though - rave albums as well as those with a deliberate "listening-oriented" ambient/IDM-approach (which also had their troubles with the 74 minutes) -, the problem was never really solved. Or rather, the best solutions seemed more to be down to pure "luck" - that is, simply having enough good and sufficiently varied material to pull of not doing anything but more of the same (i.e. the same "luck" that made many straightforward rock albums work, except that much more luck was needed in the CD age) - or some unique visionary twist that would only work with the specific style and approach of the artist coming up with it (this was of course more often the case with the IDM-leaning stuff - in the rave department, very few even remotely succeeded with this trick).

So, no one managed to invent a universally workable way to build albums out of rave music, but there was a lot of attempts, and a lot of them was actually really good - even if the majority was basically failures. Perhaps this is why I find them fascinating: The possibility of finding a good one isn't big, but it's all the more rewarding, and unexpected, when it happens. The overview below is almost certainly far from complete, I'm sure there's some obscurities, and perhaps even some obvious ones I'm unaware of, but I've tried to include as much as possible. I'm only looking at stuff that I consider "rave", which basically means music that is not trying to be deliberately "underground" and "clubby", i.e. no minimal techno, proto-IDM, deep or progressive house etc. - as well as stuff like straightforward bleep or acid. What I'm after is artists that either got to make albums because the already had hits, or made music that showed that they clearly tried to make hits, all while still staying within actual rave and techno (unlike crossover eurodance/pop like 2 Unlimited, Snap, Technotronic and their ilk). Which basically means that it's mostly within the breakbeat 'ardcore/Belgian techno/proto trance-spectrum, even though there's obviously some grey areas here and there. To avoid those as much as possible, I've also restricted myself to the years 1990-1992, because after that point, most artists had either chosen a specific subgenre path (jungle, trance, gabber), or they'd abandoned rave all together (there was some exceptions, of course, I'll look into some of the more interesting ones in the end of this list).

THE BRITISH SCENE: I've grouped the albums according to the regional scenes, starting with the British, which perhaps had the largest amount and broadest variety of rave albums. The breakbeat sound was almost uniquely British (a few continental producers used it occasionally, but basically as a deliberately added "British flavour"), and in retrospect, we think of it as being what early British rave music was, laying the foundation for jungle. But as we'll see, there was a lot more going on.

The Prodigy: Experience (1992)Pretty much the gold standard of rave albums, this is exactly how it should be done - presuming you've got the endless supply of explosive energy and inventive ideas that Liam Howlett had at this point. Despite being pretty much all hyper intense break beat 'ardcore from start to finish, Experience simply has so much going on, such an abundance of rhythmic-melodic twists and turns, that it never seems even remotely samey or single minded. It's only a slight exaggeration to say that every moment of Experience is a highlight, at the very least there's never any part of it that come off as uninspired filler material, and it's especially amazing how the tracks constantly morph and change direction - no part of them ever get a chance to grow dull or predictable before they're suddenly taken over by a new, insanely catchy hook leaping out of the speakers, taking the intensity and excitement to a new level. You'd think that this could become too much, but the greatest achievement of the album is perhaps that the sheer originality and freshness of the riffs and the way the tracks are structured, enables it to keep up that insane level of hyperactivity without ever getting exhausting or monotonous. There's the one more "experimental" track, "Weather Experience", which is perhaps not quite as memorable as the rest, but it still has enough jittery drive to not feel out of place. And the rest - well, whether it's stone cold classics like "Hyperspeed", "Charly", "Out of Space" and "Everybody in the Place", or tracks made especially for the album like "Jericho", "Wind it Up" or "Ruff in the Jungle Bizness", each of them is pretty much a mini breakbeat masterpiece in its own right, all while forming a whole that is even greater than the sum of its parts. It's hard to imagine it done better than this! Altern8: Full on - mask hysteria (1992)Much in the same vein as Experience, albeit still with some vestiges of Archer and Peats background in acid house/detroit techno/bleep (of which there were no traces in Howletts sound), and generally considered the lesser album. Which it is. It's not so much that it's closer to the hits-and-fillers-formula, it's rather that neither the hits (quite numerous, actually) nor the fillers are nowhere as good as The Prodigys hits and fillers. Most of the tracks are still pretty good, but they're also more or less standard run-of-the-mill breakbeat 'ardcore. Lots of catchy riffs and nice samples, and thankfully it never goes into crossover dance territory, so all in all not bad at all, it just doesn't really blow your mind, and in the end the genericness do get a bit longwinded in just the way that Experience so impressively manage to avoid. It definitely would have benefited from being a couple of tracks shorter. That said, it's perhaps a bit unfair to criticise it for not being of the same calibre as the definitive masterpiece of the form, and had Experience not existed, Full On - Mask Hysteria might be remembered as the purest album destillation of breakbeat rave: Far from perfect, but with plenty of the lumpen throw-away quality and cheap synthetic excitement that is all part of the charm.

Urban Hype: Conspiracy to Dance (1992)While Full On is better than its reputation, this is pretty much the platonic ideal of getting it wrong when it comes to British breakbeat rave. Known mostly for the novelty "toytown" hit "A Trip to Trumpton", you'd think Urban Hype would, at least partially, go for a playful and "tasteless" approach a la The Prodigy, but instead most of the tracks seems to aim for a slightly more "deep" vibe, or the most anonymously bland rave-pop-by-numbers combination of italo piano and soul divas. On tracks like "Relapsed" and "The Dream", the rave elements are still sufficiently raw and ecstatic to drown out the worst sirupy samples and keep them at least pretty exiting in the moment, but with "The Feeling", "Embolism" and "Living in a Fantasy", it's unfortunately the other way round, and they leave no other imprint on the memory than a slight nausea. And while the "deeper" tracks actually have some potential - especially "Teknologi part 2" and "Emotion" strike a good balance between groove, melody and atmospherics - for some reasons the lame divas and pianos are also tacked on here, as if Urabn Hype didn't actually believe that they would work as more moody pieces after all, and eventually ruining them in the process.

Shades of Rhythm: Shades (1991)Shades of Rhythm were unusually prolific on the album front, although a lot of the same tracks appeared on 1989's Frequency, 1991's Shades and 1992's The Album. Where the last one was pretty much just a slight update of Shades, Frequency is in a more rough, house/acid-derived bleep'n'breaks style, and not quite rave yet - despite the presence of the hits "Homicide" and "The Exorcist". In any case, I guess Shades is the "classic" Shades of Rhythm album, but unfortunately it gets it wrong in much the same way as the Urban Hype-album. There are some good tracks on it - in addition to the aforementioned hits there's also heavy bleep'n'breaks workouts like "The Scientist" and "666 - the no. of the bass" - but then there's also the archetypical potentially-great-but-ruined-by-soul-diva-sugar-coating of "Sweet Sensation", as well as far, far too much horrible soul-jazzy deep house-ish dreck like "Shakers", "The Sound of Eden" and "Lonely Days, Lonely Nights", making it a bit of an endurance test listening to the album as a whole.

The Hypnotist: Let Us Pray - the complete hypnotist 91-92 (1992)Refreshingly devoid of crossover dance and soulful "deepness", this is pretty much a collection of straightforward rave singles with a few unreleased tracks added, and drawing on both the continental brutalist sound as well as British breakbeats. While this is obviously a good thing, Let Us Pray unfortunately doesn't work quite as well as it could have, because even though none of the tracks are bad, a lot of them are also sort of generic and samey, and as a result it isn't able to stay exciting for the 80-minute playing time. Too many tracks follow the same minimally surprising structure, and lack the wellspring of original ideas and hooks that made Liam Howlett able to pull off an hour of the same hectic sound without ever getting boring. That said, and despite missing "The Ride" - arguably his greatest track ever -, there's plenty of classics here ("House is Mine", "Hardcore you know the score" and "God of the Universe" to name a few), and as such it works pretty great as a collection, an archival overview of Caspar Pounds contribution to rave music. It's just not something that it makes much sense to listen to as a whole. Had it been trimmed down to half the length, it could have been really great, but as it is, the sharp blast of the Hardcore ep is a much better suggestion for the definitive Hypnotist record.

Rhythmatic: Energy on Vinyl (1992)A wonderfully compact and straightforward little album - basically an EP extended to an eight track mini LP -, and more or less getting it right where Urban Hype and Shades of Rhythm got it wrong: There's plenty of stylistic variety, stretching from full on rave mania to more atmospheric sparseness, but it never degenerates to mainstream dance or tasteful, tedious "deepness", and it's never just doing styles-by-numbers. This might actually be the best thing about it - there's elements of breakbeat 'ardcore, bleep'n'bass, Belgian techno and even some house/Detroit vestiges here and there (it is on Network), but it's all mixed up into unique, constantly morphing concoctions, doing all sorts of weird and unexpected tricks and twists and never really being one single thing - except that it's all, in one way or another, rave music, pulsing with synthetic energy and jittery intensity. Sure, there's a few elements I could do without (the rapper on "Nu-Groove", the few examples of soul divas, i.e. the usual suspects), but exactly because the tracks change and evolve all the time, those elements never get stuck long enough to become annoying. Energy on Vinyl is one of the greatest overlooked gems of the early British rave scene.

N-Joi: Live in Manchester (1992)Despite being some of the most successful hitmakers on the British rave scene, N-Joi didn't release a proper album until 1995, the rather tame and polished, progressive-housey Inside Out, long after the heyday of their original signature sound. They did make this brilliant "live" mini-LP, though, a just-short-of-30-minutes non-stop barrage of breaks, hooks and buzzing riffs that seems like a much better shot at finding an effective rave album formula than most proper rave albums. Reputedly an after-the-fact studio reconstruction, Live in Manchester creates a cheap laboratory-facsimile of the "real" thing, a buffet of one-dimensional, yet thrillingly synthetic, empty rave calories.

Eon: Void Dweller (1992)Every time I start listening to this, I immediately think it's going to be a brilliant album, which is hardly surprising, given that it takes off with three of Eons catchiest tracks - "Bakset Case", "Inner Mind" and "Fear" - , all offering an abundance of exiting riffs and samples, as well as a highly original sound somewhere between the dominating rave of the day and a kind of proto big beat, as you might expect from something that involves J. Saul Kane. So why doesn't the album stay brilliant? Well, it's not just that the majority of the rest of the tracks are a bit more laid back and atmospheric (with a few exceptions, i.e. "Spice"), it's more that this means that they're less intent on being exciting, and the resulting slightly lower quota of wild sounds and samples draws your attention to the fact that the compositions in themselves haven't that much to offer - there aren't any really memorable hooks or melodies, or exiting structural ideas. Not that there has to be, of course, it's still an original and enjoyable album in many ways, it just doesn't grab the attention all the way as it should, and would have benefitted highly from being two or three tracks shorter.

Shut Up and Dance: Dance Before the Police Comes (1991)Ragga Twins: Reggae Owes Me Money (1991)Rum & Black: Without Ice (1991)I've talked about Ragga Twins and SUAD before, and they only tangentially belong here, given that rave elements only appear as parts of a broader, cross over-hybrid sound with an emphasis on vocals. There's some quite ravey tracks on them for sure, but there's even more where the rap is the main thing, and though enjoyable (well, mostly SUAD, I've never been completely convinced by the twins I must admit), neither Dance Before the Police Comes or Reggae Owes Me Money really work as rave albums. In comparison, Without Ice is a much "purer" album, in that it's pretty much proto breakbeat darkcore from start to finish. Not that it makes it one dimensional, there's both energetic rave, more sparse and gloomy atmospherics, as well as a lot of tracks that combine a bit of both. As such, I suppose it could have been great, but unfortunately, there's really not a lot of ideas in each of the many, many tracks - there's some good and interesting sample choices (Sakamoto, lots of Art of Noise), and the breaks are often treated so that they have a great, synthetic edge to them, but in the end, all tracks more or less just consist of a couple of simple, interchanging loops. It can sound great in smaller doses, but with a 50 minute playing time it eventually becomes a bit of a drag, where it's difficult to tell the tracks apart.

THE GERMAN SCENE: Despite being the only rave scene with a size and variety comparable to the British, early German rave has always been a bit overshadowed by its Belgian contemporaries, which had a few more hits of a broader, international impact. They do have a lot in common - in particular the EBM and new beat-elements, but in Germany that became even more pronounced and electroid, reflecting the importance of the early Frankfurt scene and its roots in new wave and industrial. Still, there's also many other elements present.

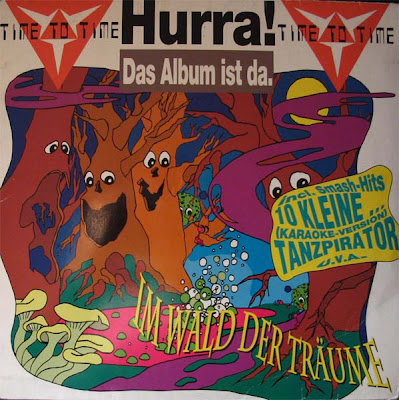

Time to Time: Im Wald der Träume (1991)Equal parts rave euphoria, EBM/synth wave-coldness and infantile German humour, Im Wald der Träume is still as charming and paradoxical as the first time I wrote about it. As much an absurdist deconstruction as perhaps the purest distillation of rave silliness around, it's an unique and wonderfully bizarre artefact from a time where it was still pretty open what rave could and should be - there isn't really anything else like it.

Twin EQ: The Megablast (1991)Much like Rhythmatics Energy on Vinyl, and as mentioned elsewhere, this is a short and intense LP that very much sound like it was slapped together in a hurry (as I'm sure it was, the Lissat/Zenker-duo was hyper-productive back then), and it contain no recognizable classics, yet it's all the more charming for it. In addition to plenty of buzzing riffs and stomping beats, there's also 8-bit elements ("Hardcore Keyboard") and even weird machinic acid ("Enjoy"), but in the end it all has a sort of clunky functionality that suggests that this was made by people who were fully aware that they were churning out soulless rave fodder, and just decided to have fun with it, revelling in the cheap, inauthentic-synthetic aesthetic.

Interactive: Intercollection (1992)Interestingly, and despite obviously trying to build on their previous hits, the debut album from Lissat and Zenkers most successful and well know project was not nearly as convincing as the practically forgotten Twin EQ-LP. In addition to "Who is Elvis", the first and most likely biggest in what would eventually become a series of gimmicky novelty-hits, many of the tracks here were minor hits on the early German rave scene, and exhibit the typical combination of EBM-coldness and Belgian brutalism (with new beat as the mediating factor). Arguably, the more minimal and restrained approach of this sound didn't work in Interactives favour, they didn't let loose with as many deliciously synthetic sounds and raw ideas as on The Megablast, though that is not to say that there isn't some pretty great tracks on The Intercollection - "The Techno Wave", "No Control" and "Dance Motherfucker" are all brilliant examples of the style - they just dolose some immediate freshness as they go on. The albums biggest problem, though, and the reason it isn't nearly as good as it could have been, is the fillers, which don't really offer much - again unlike The Megablast, which pretty much was nothing but exciting fillers.

Westbam: A Practising Maniac at Work (1992)Westbam is an interesting character in German rave history; one of its most successful and enduring DJs, figurehead and main brain behind the massive, epoch-defining Mayday mega raves, yet at the same time having a somewhat unusual background, more resembling the British DJ-tradition, raised on hip hop and proto-house, than the typical German EBM/new beat-route. Already a bit of a veteran in 1992, his previous two albums were more in a clear hip house-vein, and it would seem obvious that he would go into breakbeats when going full on rave with A Practising Maniac at Work, but instead, at least to some degree, he approached the more straightforwardly bruising, linear sound domineering the continental dancefloors at the time. Not that we're talking full on Belgian brutalism, there's still hip house vestiges and plenty of uplifting breaks and samples, but rather you get a kind of fusion between these elements and the harder, more cyber-cubist stuff. This actually makes it a somewhat original album, though not a very consistent one - some of the more housey and/or eclectically experimental tracks, like "Acid Snail Invasion" and "Street Corner", just goes nowhere. Westbam is definitely best when he's clearly trying to make fast paced dancefloor functionality or straight up anthems, and he is able to make invigorating and somewhat cheesy rave fodder if he wants to, but here there's a bit too little of that to make a really powerful album. It's still enjoyable, the boring stuff is not too dominant and there's thankfully no cringeworthy dance-crossover attempts, but as a pure rave album, it's too uneven.

U96: Das Boot (1992)I love the humour of the cover hyperbole: "The TV-advertised mega-seller album including at least 10 top-ten hits". Das Boot contain exactly ten tracks, with several clearly being fillers, included only to reach a playing time of at least a short album. But clocking in at slightly over 40 minutes is actually a benefit here - U96 doesn't have that many ideas, so the fast pace of the whole thing means that some weaker elements (mostly) doesn't become annoyances. As a result, this is definitely one of the best cashing-in-on-a-one-hit-wonder albums of the entire rave era. In addition to some actually convincing examples of slow and dreamy "atmospheric fillers", including an odd yet oddly charming "Moments in Love"-pastiche, Das Boot is basically abrasive Belgian brutalism tinged with a few whiffs of the colder, EBM-derived German sound, and except for the misnamed "Ambient Underworld", which could have been good but is completely ruined by lame rap and a histrionic soul sample - it delivers just the kind of great "more-of-the-same"-rave tracks that you usually hope for with this kind of album, but far too rarely get.

Time Modem: Transforming Tune (1992)By far the best album based on the EBM-derived rave sound, and basically just one of the greatest, most consistent and convincing solutions to the whole rave album conundrum. Eventually, at least on the shorter and more condensed vinyl version, it's only 50% rave tunes, with the rest being atmospheric mood tracks, but the two elements frame each other so brilliantly that it all just seems like a whole, simultaneously a blinding rave album that works as pure listening experience, and a sort of futuristic concept album that just happen to work as blinding rave music as well. The softer tracks are interesting in that they're not really excursions into already established moody electronics, like ambient or soft house, but mostly a further mutation of the elements used in the harder rave-tracks - epic chorus-pads, fanfare-like melody riffs, driving EBM sequencer-bass -, all turned dreamy and melancholically introverted. The bittersweet ambiguity is obviously a part of Time Modem's EBM/new wave-genes, and even permeates the rave tracks, most brilliantly on "Welcome to the 90's", the pinnacle of, and key to, the album. Over hectically opulent, yet mercilessly focused rave, an aloof voice embody naïve early nineties cyber-futuristic excitement, with sentences like "we don't need the sun anymore" and, as far as I can hear; "greed is the means to success", but countered by what sound like movie samples in German, shouting bitterly about the horrible state of the world, including the phrase "es ist alles luege" ("it is all lies"). I get the impression that Transforming Tune reflect the ambivalence felt by rave artists coming from older EBM/industrial-derived techno - on the one hand swept away by the hope and celebratory spirit of rave as the soundtrack to the future and a unified Germany, on the other hand still influenced by EBMs dystopian, cyber-punk view of technology. This seems further supported by the closing track "Space and Time", sort of a defeatist hymn to isolation and alienation through technology, with a melancholy girls voice uttering phrases like "take the headphone and flow away, want to be one with my sound" and "cannot forget my reality, eternally apart and loneliness" - a heartbreakingly precise prediction in many ways, and the perfect way to end an album that successfully manages to be invigorating rave, ambiguous electronic mood music, and conceptual futurism all at once! A lost gem if ever there was one.

New Scene: Waves (1992)Coming from the same scene as Time Modem, but with the EBM and new/cold/dark-wave elements much more dominant, this is only full-on rave music on two tracks - "Sucken" and "PSG 22" - while the rest is somewhere between proto trance and the same sort of slowly drifting, atmospheric not-quite-ambient that was also found on Transforming Tune. The more streamlined, dark and restrained sound makes Wavesa contemplative experience rather than a rave album, but I think it's still worth including here, not just because it pretty good on its own terms, but also because it represent a strange and unique alternative way to turn techno into home listening music, completely different from the path taken by the IDM and ambient scenes, and in many ways not really sounding like anything else: Beneath the dark and dreamy surface, the underlying structures of the tracks - the way they're built - is still clearly recognisable as early nineties continental rave techno. O: From Beyond (1992)The first album from one Martin Damm, who would eventually release countless records of almost all kinds of hardcore, rave and techno, under a plethora of pseudonyms like Biochip C, Search and Destroy and The Speed Freak. Though there aren't many remnants of it on his later releases, he started out in much the same EBM/new beat/electro-based area of continental rave as Time Modem and New Scene, and From Beyond is also a combination of old school German rave, proto trance and epic synthscapes. It's a bit on the long side, with a few less-than-inspired tracks, which I guess could partly be blamed on the fact that, unlike Transforming Tune and Waves, this is a CD-only release, and therefore doesn't benefit from being trimmed down to a more focused single LP, as those albums were. Still, there's a lot of really good stuff here, and especially the atmospheric synth tracks have an endearingly-dated period charm, though many would probably find their swelling pads and cod-epic melodies too much. Personally, I find this aspect of the album fascinating - as with the two previous ones, a glimpse of a completely forgotten road not travelled.

New Scene: Waves (1992)Coming from the same scene as Time Modem, but with the EBM and new/cold/dark-wave elements much more dominant, this is only full-on rave music on two tracks - "Sucken" and "PSG 22" - while the rest is somewhere between proto trance and the same sort of slowly drifting, atmospheric not-quite-ambient that was also found on Transforming Tune. The more streamlined, dark and restrained sound makes Wavesa contemplative experience rather than a rave album, but I think it's still worth including here, not just because it pretty good on its own terms, but also because it represent a strange and unique alternative way to turn techno into home listening music, completely different from the path taken by the IDM and ambient scenes, and in many ways not really sounding like anything else: Beneath the dark and dreamy surface, the underlying structures of the tracks - the way they're built - is still clearly recognisable as early nineties continental rave techno. O: From Beyond (1992)The first album from one Martin Damm, who would eventually release countless records of almost all kinds of hardcore, rave and techno, under a plethora of pseudonyms like Biochip C, Search and Destroy and The Speed Freak. Though there aren't many remnants of it on his later releases, he started out in much the same EBM/new beat/electro-based area of continental rave as Time Modem and New Scene, and From Beyond is also a combination of old school German rave, proto trance and epic synthscapes. It's a bit on the long side, with a few less-than-inspired tracks, which I guess could partly be blamed on the fact that, unlike Transforming Tune and Waves, this is a CD-only release, and therefore doesn't benefit from being trimmed down to a more focused single LP, as those albums were. Still, there's a lot of really good stuff here, and especially the atmospheric synth tracks have an endearingly-dated period charm, though many would probably find their swelling pads and cod-epic melodies too much. Personally, I find this aspect of the album fascinating - as with the two previous ones, a glimpse of a completely forgotten road not travelled. Space Cube: Machine & Motion (1992) A bit of an outsider here, Space Cube started out making more ravey tracks, and are often remembered as one of the few early German rave acts to use breakbeats, but on the debut album Machine and Motion, they worked with a lot of different elements, including pounding techno and drifting acid, as well as - unfortunately - quite a bit of house, foreshadowing Ian Pooleys later career. The result is simultaneously varied and somewhat more "pure" than most records on this list - as in "not cheesy" and "closer to proper dark'n'deep minimal techno". Which eventually makes it a bit too "nice" and anonymous to my ears. There's some really good tracks on it, such as the 80Aum/T99-ish brutalist "Disruptive" and the UR-acid-spacey "Forbidden Planet", but as a whole there's too much good taste and relaxed smoothness for it to be really convincing as a rave album. Perhaps it could be seen as a good example of how there still weren't any clear genre borders at this time, and how an album from the rave/techno-scene could contain many different styles and ideas, and on those terms I guess it has merit - many of the softer tracks are not bad at all - but I'd still much rather listen to an album one dimensional "rave fodder" than this exercise in well-crafted style and diversity.

THE BELGIAN/DUTCH SCENE: It's strange that Belgium usually gets all the credit here, because the infamous brutalist sound was as much the responsibility of Dutch producers - several of the classics that are by convention considered Belgian (like Human Resource or 80 Aum) were indeed Dutch. Of course, the Belgians didhave the EBM and especially new beat-scenes to draw on, which could explain why - when it came to albums - they seemed a bit more prolific. In the end, though, the rave made in the two countries was generally so similar that it makes little sense separating them, which actually is a bit strange, considering that the Dutch producers had roots in hip hop and italo disco, rather than new beat/EBM, and eventually went on to create gabber, while the Belgian producers more or less disappeared from the techno map subsequently.

Human Resource: Dominating the World (1991)According to some guy on discogs, this was actually released prior to "Dominator" becoming the huge hit that it was, making it a very odd thing on this list: An album that produced a classic track, rather than being produced to cash in on an already established classic. Given the title, though, they were at the very least aware of the tracks potential, but in addition to that, there's actually a lot of quality stuff present here, especially in the beginning, with inventive and well produced, slightly more atmospheric (but still highly invigorating) tracks like "The Joke" and "Faces of the Moon". Unfortunately, much like Eons Void Dweller, as the album goes on the tracks become less interesting - still very well constructed, but more or less lacking really memorable hooks or sounds, or the general raw power usually associated with the Belgian sound that "Dominator" played such a big part in developing. Furthermore, remixes of "The Joke" and "Dominator" - nice as they are - makes the album longer than it had to be, and the lack of new ideas on the second half becomes even more obvious.

LA Style: The Album (1992)Of all the one hit rave wonders, LA Style had the biggest challenge with creating an album, and sadly, they weren't up for that challenge at all. Not only was "James Brown is Dead" the biggest and most iconic of all the brutalist hits, it was also based on such an idiosyncratic and immediately recognisable riff that it was pretty much impossible to expand upon it - it was painfully clear how the countless clones that sprouted overnight tried to recreate the exhilaration of the fanfare blast, and you'd recognise this right away. "James Brown is Dead" is simply impossible to take any further (the sound alone - it actually managed to give the impression of realizing the old joke: make everything lounder than everything else!), and it might seem a bit like a novelty-track in this way, but don't get me wrong; it's arguably the greatest rave track ever exactly because of this - rather than a "gimmick", it's a singular stroke of genius. And how do you cash in on that, without repeating yourself ad nauseam? Well, don't ask LA Style, because that's just what they did - pretty much every single track on The Album recycles the "James Brown"-riff in one form or another. At best it gets more baroque and exaggerated, as on "LA Style Theme" - though that track could pretty much be called a "James Brown is Dead"-remix -, other times it regress back into something slightly more italo-piano-ish, and far far too often there's added a hearty dose of the most generic early nineties dance rap-and-soul imaginable. A few moments have merit, but only when they're repeating what was already perfect on "James Brown is Dead" - that single is still all the LA Style you need, and nothing is added here that changes that.

T99: Children of Chaos (1992)Next to "James Brown is Dead" and "Dominator", T99s "Anasthasia" is probably the greatest belg-core hit of all time, but unfortunately the album based on it isn't much better than the two previous ones. It's not for lack of trying, though, as T99 clearly wants to make a varied and coherent whole, rather than just a bunch of "Anasthasia"-clones. Now, a bunch of "Anasthasia"-clones would probably have been a lot better than this mess of crossover rave and more or less successful attempts to make laid back tracks, but the latter actually dohave some merit, Patrick De Meyer and Oliver Abbeloos are excellent craftsmen and they know how to create a good tune with good futuristic sounds at low speeds as well (despite some annoyingly "musical" elements like the nauseating sax sample on "After Beyond"). The biggest problem on Children of Chaos is the insufferable amounts of tacked on vocals - the usual lame rapping and cringeworthy soul divas - that render otherwise brilliant rave tracks like "Maximizor", "Cardiac" and "Nocturne" almost unlistenable. And it's really a shame, for had the album kept to just raw synthetics, and perhaps scaled down the amount of atmospheric tracks slightly while developing some of the shorter rave sketches a bit, this could really have been the Belgian rave album. But then, you could say something similart about most of these.

Quadrophonia: Cozmic Jam (1991)Prior to his succes with T99, Oliver Abbeloos also had a couple of hits together with Lucien Foort as Qadrophonia. Containing many of the classic Belgian elements - exhilarating blasts of raw angular bombast - as well as a surprising amount of breakbeats, Cosmic Jam unfortunately also contain extremely dated rapping on all tracks but a few short interludes. I guess this was a conscious choice, trying to give them a bit more personality (much like with added vocalists of 2 Unlimited) bit it completely ruins what could otherwise have been a pretty good - if perhaps a bit long - rave album.

Pleasure Game: Le Dormeur (1991)Le DormeurI've talked about before, and though it still has its flaws - most tracks are slightly abbreviated, and there's a couple of somewhat uninspired "ambient" fillers - it also remains one of the most straightforward and convincing of the early nineties rave albums. Actually, of the Belgian albums, only one was better, and interestingly, that was made more or less by the same people.

DJ PC: 100%(1992)While DJPC was fronted by DJ Patrick Cools, the production team behind the project included Pleasure Games Jacky Meurisse and Bruno Van Garsse - both coming from the EBM/new beat-outfit SA42 - and with 100% they made the ultimate Belgian rave record, the album that Human Resource or LA Style or T99 should have made. Some tracks are better than others, but even when they're a bit too gimmicky ('Return of Tarzan', 'Di Da Da, Di Da Di Da Da'), or ridiculously bombastic-by-the-numbers ('Control Expansion'), they're still super effective, focused and exhilaratingly brutal. And the best tracks are just incredibly good, all ugly angular machine music, relentless mentasm madness, and not a guest vocalist or smooth'n'laid back track in sight.

Hypp & Krimson: Rave Sensation (1991)Containing tracks released under six different names, this is sometimes listed as a compilation. Everything is produced by the duo of Jeff Vanbockryck and Patrick Claesen, though, with different collaborators here and there. We get the instrumental versions for a couple of Miss Nicky Trax productions, well known Ravebusters-classics "Mitrax" and "Power Plant" (though for some reason the latter is accredited to Hypp & Krimson)showing their roots in new beat, and in addition several unknown (to me) gems in the same vein, like "Torsion", "Dreams Forever" (as Code Red) and "Liquid Empire" (as Cold Sensation) - heavy rave fodder that isn't all that inventive or catchy, but makes up for it with precision-locked efficiency. The weakest part is the more floaty, atmospheric offerings - one of the Nicky trax and the not very aptly named "Rave Banging" - they're not exactly bad, just pretty uninspired, and they do create a couple of dull drops in the overall energy flow. As a result, Rave Sensation doesn't completely live up to its name, but it's not too far off either, and certainly one of the more consistent of the belgian albums.

Holy Noise: Organoized Crime (1991) Perhaps the greatest of the Dutch rave producers, Holy Noise was where DJ Paul got his first real success with tracks like "The Nightmare" and especially "James Brown is Still Alive!!", his riposte to LA Style, before he became a key player on the emerging gabber scene. As such, he's one of the only Benelux producers to have a noteworthy career after the rave heyday, as well as perhaps the most obvious link between gabber and the early brutalist rave sound. Organoized Crime is one of the better lowland albums, even though it sort of disappoints because it could easily have been so much better. While no tracks are bad as such, and several are really great, there's also a couple that are a bit too mediocre - in particular more minimalist ones like "House Orgasm" and "The Noise", and since the album is much longer than it has to be, it just becomes a bit exhausting overall. If the two aforementioned tracks were kicked out, as well as one of the two versions of "Get Down Everybody", we'd have an absolute classic here, one for the rave album top ten. Instead, we get something that do contain a lot of good stuff, but eventually looses its steam before you're through.

OTHERS: Two (or perhaps rather two and a half) other local scenes needs mentioning, being big enough to eventually produce full length rave albums (that I've heard of). Yet they're very different - the Italians produced endless amounts of generic (and often brilliant) rave fodder, a variant of the brutalist sound more or less infused with elements of italo disco and italo house, while the rave proper produced by the American scene seemed like maverick attempts to participate in what was going on in Europe, rather than a reflection of an overall American sound. Finally, the odd Spanish "makina"-scene was arguably closest to the early German rave, with EBM and new wave still very clearly present.

Moby: Moby(1992)This amazing LP will be a bit of a surprise to anyone only familiar with the later emo-Moby - or anyone who think "Go" is representative of his early style. What you get is a tour de force of almost perfect rave intensity, with "Go" and the closing "Slight Return" being the only softcore tracks. Sure, the first half is by far the best, and there's a house piano here and a soul sample there that you could certainly do without, but there's only a few of these (and let's be fair - even The Prodigys Experience had a couple), and they're not prominent enough to do any real damage to what is otherwise a brilliant collection of tracks, action packed with jittery ideas, catchy sequencer riffs and dynamic twists and turns. Whether it's near-claustrophobic EBM-ish tightness ("Yeah", "Have You Seen My Baby"), strings'n'acid-driven brightness ("Help Me to Believe"), or explosive, unhinged rave-insanity (pretty much all of side A), none of the tracks are bad - and some of them are simply among the very best of the era. This is pretty much the only Moby album you need - but if you're after early nineties rave then you really do need it (and who'd have thought you really needed any Moby at all?). As rave-albums-that-works-as-albums go, Mobyis among the very best.

Oh-Bonic: Power Surge (1992)A brilliant little album that sadly seems to be completely forgotten. As far as I can figure out, Oh-Bonic was basically Omar Santana, who has followed a long and pretty weird trajectory through electronic dance music: Starting out as a part of Cutting Records early electro/house famil, and eventually ending up (last time I checked, anyway) producing bizarre "patriotic gabber" in the wake of 9.11 - presumably distancing himself from his earlier New York Terrorist-moniker, which I guess didn't seem that funny anymore. In between, however, there was both a more ordinary gabber/hardcore phase (much in the typical Industrial Strength/Brooklyn vein), as well as an earlier phase of awesome, brutalist rave - with Power Surge as the crowning achievement. Here, all the most obvious and effective rave elements are supercharged by generous inspiration - every track is jam packed with ideas and variation, constantly shifting and adding small electrifying details - as well as a knack for catchy riffs. Much like the early Prodigy in this respect, actually. The only downside is the tacked-on rap that makes a couple of otherwise excellent tracks seem cringeworthily dated - in one case made even worse by a liberal dose of soul diva samples. With the rest of the album being so pure in its super synthetic sound design, these attempts at adding a human emotional element just makes it seem much more mundane and backwards-looking. Not so much, though, that Power Surge isn't still a small gem in the same vein as Energy on Vinyl and The Megablast, well worth tracking down.

Digital Boy: Futuristik (1991)Digital Boy: Technologiko (1991)With two albums in one year, Digital Boy was one of the most prolific of the Italian producers, and probably the closest we get to a household name from that scene. In a lot of ways I really want to like the ambitious Futuristik double LP, it has a lot going for it: A good title and a ridiculous cover, a couple of really good, catchy rave tracks, and some unexpected oddball moments (a bleep'n'bass-ish xylophone-riff here, a playful rip off of Speedy J's 'Pullover' there, a live track that actually sounds live). And while there's also a lot of more uninspired, clumsy fillers that doesn't quite reach escape velocity, there's only a few tracks that are really awful (especially "Touch Me", a horrid attempt at a kind of smooooooth hip house torch song). The problem is that it just goes on for such a long time, which means that the mediocre stuff that would be acceptable in smaller doses on a more focused album, eventually becomes the defining character here, and rather than being invigorating like the best rave should be, it kind of loses all momentum in the long run. Luckily, Technologiko gets it right - a super condensed eight track mini-LP that just deliver functional rave fodder in the most hook-filled, simple and electrifying way. None of the tracks are lost classics, but there's no real duds either: They all work the formula brilliantly, and like The Megablast, Energy on Vinyl or Power Surge, the result is a record that captures raves single-minded, disposable hyper-excitement perfectly, exactly by having no other ambition than being a short, one-dimensional energy blast.

Bit-Max: Galaxy (1992)Pretty much as concentrated italo-techno as it gets: Generic-yet-explosive rave tools by a bunch of virtually unknown producers (the only ubiquitous one on the album being one Maurizio Pavesi), overdosing on all the most effective euro-rave elements (mentasm stabs, hypnotic EBM arpeggios, bombastic fanfare blasts - though, thankfully, no pianos), with half of it sounding suspiciously like something you've heard somewhere before. And - of course - there's several otherwise brilliant tracks that are ruined by relentless diva samples, which prevent Galaxy from being up there with the very best. But there's still plenty of good stuff to make it highly recommended to anyone into golden era rave at its most gloriously mercenary.

Teknika: Yo No Pienso en la Muerte (1991)This is the only example I've got from the Spanish "makina"-scene, basically a local take on EBM-influenced rave in the same vein as German acts like Time Modem and 'O'. I suppose there's a lot more out there, but at least for albums, I've not located any others (not that I've tried that hard, it must be said). In any case, it's an effective mini LP, where most tracks deliver a relentlessly propulsive, slightly more minimal and machinic version of the aforementioned German sound. A couple of melancholic tracks are thrown in for variety, sounding somewhat dated, but in a charming way - sort of instrumental "minimal wave" rather than the floating, complex mood pieces that the German acts were doing. A nice little album that holds together very well.

AFTERTHOUGHTS: By 1993, "rave" as an overall term had more or less disappeared, or rather, had split up into fully self sufficient and clearly distinct niches like darkcore/proto-jungle, trance, gabber/happy hardcore or even "techno", which had hitherto been an overall term used for pretty much all the rave forms, but now suddenly became more and more synonymous with pounding minimal functionalism. Still, there were some producers left who in one way or another continued making "rave" at a time where there wasn't really a scene for non-specialized rave any more. Whether they simply were a bit too slow following the changing landscape, just had some tracks left that would have been perfectly up to date a year prior, or deliberately tried to create a continuation of the general, all-encompassing rave spirit, I find these out-of-time rave albums fascinating, and deserving some mention. Indeed, some of them are truly brilliant in their own right.

GTO: Tip of the Iceberg (1993)In many ways a very sympathetic album, wrapping the classic "old faves + some new fillers"-formula in a pan-stylistic, almost meta-rave "unite-the-scene"-concept, at a time when the rave scene was busy splitting up. We more or less get everything from piledriving gabber and hardcore over cold, monolithic trance to softer, more housey tracks, sometimes with an almost bleep'n'bass-feel. The weird thing is how none of this sounds quite right, but rather like someone decided to make trance or gabber, rather than growing it organically from within a scene. This certainly gives Tip of the Iceberg an original sound, but it also means that it doesn't really manage to create the feel of rave-distilled-in-album-form that it seems to aim for. In particular, there's an awkward minimalistic restraint to it, at odds with the cutting-loose-and-going-mental effect you'd usually expect with these styles. This goes for the sound design - strangely polished and empty even in the raw'n'ruff hardcore tracks - as well as the compositions, where there aren't that many ideas or really memorable hooks around. It eventually becomes a problem for an album as long as this. In smaller doses - like side B with its metal machine gabber, or the more hit-oriented side C -, it's quite enjoyable, but as a whole, and especially with the two somewhat uninspired and monotonously minimal closing tracks, Tip of the Iceberg gets a bit tiring. Which is a shame for a record that so deliberately and head-on try to solve the rave-album-problem. That said, it remains refreshingly odd.

Sonic Experience: Def til Dawn (1993)An unabashed "meta rave" effort, where raw and ruff breakbeat tracks are interlaced with sound clips from open air raves (mostly police confrontations). The clips are sort of charming, I guess, but they do make the LP feel more like a kind of "historic document", rather than simply a great collection of generic-yet-invigorating 'ardcore at its most unpolished - which is basically what it is. But perhaps what Def til Dawn shows is that by 1993 this sound was already seen as something to look back upon nostalgically, as things had moved much further ahead. A great snapshot of an era that was over almost as soon as it had started.

Sonz of a Loop da Loop Era: Flowers in My Garden (1993)Just a mini-LP, but worth including here as it's the closest we get to a Sonz of Loop da Loop Era-album. Perhaps its shortness is an advantage, as all six tracks capture Danny Breaks at his b-boy derived best, filled to the brink with jittery riffs and hyperkinetic breaks (more proto big beat than 'ardcore on "Breaks Theme pt. 1", but still great), with no time to fall into any of the traps so many others fall into when having to deliver a full album. Flowers in My Garden might not be as catchy and relentless as Experience, but it's a pure distillation of 'ardcore at its most un-assumedly loose and playful.

Criminal Minds: Mind Bomb (1993)

The flipside to Sonz of a Loop's silly and colourful sound, Mind Bomb is a much more raw and aggressive take on 'ardcore. There's quite a lot of slightly (for its time) backwards-looking techno-elements, as well as plenty of proto-jungle, just not dominant enough for it to actually be jungle (unlike, say, Bay B Kane's Guardian od Ruff or A Guy Called Gerald's 28 Gun Badboy, which are arguably just on the other side of the divide - perhaps not fully developed jungle yet, but still closer to jungle than to breakbeat rave). None of the tracks are super memorable or lost gems, but neither are any of them bad - they're hectic, rough and hard-hitting examples of generic hip hop-influenced 'ardcore of the kind where the genericness is a crucial element, and as such it is perhaps the most "authentic" example of this music in album form.

As expected, he didn't buy that the poststep stuff is as great as I'm claiming it is. The interesting thing in this respect is the claim that he actually has tried (as stated in the comments), but it just doesn't click. In a way this takes the problem to a different level, not about poststep per se, but about how we react to music, what it means for someone to really get something, and not least: whether really feeling, or not feeling, something, is really an argument for its merit or lack thereof? Personally, there's a lot of stuff I know I ought to like, but that just doesn't do anything for me; which seems pointless and uncommunicative (in the derogatory sense Reynolds is using here - I certainly find some deliberately uncommunicative music deeply fascinating). Something like Velvet Underground could be a good example. All right-thinking people seem to agree that this is simple the most important and amazing rock music ever made, but nevertheless, it leaves me completely cold. Sure, it's mildly interesting when I'm listening to it, but not to a degree where I'm not also slightly bored, and afterwards, I have no wish to ever hear them again. That doesn't mean that I can't see its historical importance - tons of stuff I love (krautrock, post punk, noise rock and dreampop) are deeply indebted to VU, might not even have existed without them. But just because something is revolutionary on a technical level, it doesn't make it the best example of the trend it started. The noise/avant garde-element is still very rudimentary and one-dimensional (not enough Cale), and Lou Reed's song writing is mostly just dull. And yet, even though I've tried "getting" Velvet Underground for many years, and still barely remembers any of it, I'll accept that they are, in a way, "objectively good", I just don't find them subjectively good. I'll grant that they have an important place in the historical archives. There's just many other parts of those archives that I'd much rather like to spend my time with. Such as the best post step, which as far as I see it, isn't just subjectively good, but truly objectively good as well.

The question then is: by what objective criteria? Well, most likely not by how influential it has been (probably the best argument for VUs "importance"), as I doubt most of it will have much influence at all. But then, I think most of us have favourite records that have had very limited subsequent impact, and which we yet would consider truly "good" by some other criteria. Most obviously, I think it should be about originality - creating musical structures that have not been heard before, and yet truly is "structures" (which is what makes it work as music, makes it relatable and fascinating), rather than just pure randomness. But already there's a problem here, because judging if something "has been heard before" or creates a "relatable structure" certainly involve some quite subjective elements. One person's deeply engaging structural originality is the next one's empty indulgence, and as I talked a lot about last time, it's highly relative how "new" something will sound to different people. That said, it seems that Reynolds is acknowledging that there is some formal newness going on in post step, it's just that, as he doesn't connect with the music, then obviously something else must be amiss (and there has to be something wrong with it when he's not feeling it - much like I just tried to explain what is "wrong" with Velvet Underground, because it doesn't seem to be satisfactory that it's simply be a matter of taste whether you're getting something that is "objectively good" or not).

So what is missing, according to Reynolds? Sort of the usual rockish suspects, I guess: Social energy, functionality (being useful), viscerality, bursting-into-the-world, smashing-up, cutting loose, "brocking out". I think there's a least two questions to consider here - 1: why should it be a problem that these elements are absent? And furthermore - 2: are they actually absent? Or rather, in what way can we determine that they're absent, except whether we simply feel them being there?

As for the first question, one of the returning themes in my writings on post-step is that I think it's a huge fallacy to measure it by a 'nuumologically calibrated brock-o-meter. The social chemistry of cutting-loose-on-the-dancefloor is notthe point of this music - or at least most of it -, and saying that it is lacking in this department is a bit like saying sixties electro-acoustic avant garde is "lacking" the passionate social interaction of tango or waltz. I mean, it certainly doesn't have that element, but then, it's not really something it ought to have. It's not that I disagree with the point that "with dance music you want to be getting your rocks off", but most post-step is simply not meantto be heard as dance music - not supposed to belong to the same continuum as Foghat and Slipmatt, but rather - if anything - the same as Subotnick and Schnitzler, Mouse on Mars and The Black Dog. Or, I'd say, as Chrome and Wire. Because once again I think post punk is the obvious analogy - do post punk belong in the cerebral "listening" department that Reynolds have no problem with in itself, or as part of the "brock continuum" that he identifies as running from garage rock all the way through punk and rave to present day hip hop? Post punk is conspicuously absent from his long youtube brock-list, with the quite rock-ish Killing Joke as the only example. Which is not to say that you couldn't find a few more brocking post punkers if you wanted to, but wasn't it exactly the whole pointof most post punk to question and deconstruct that very (b)rockist "essence". Huge swathes of it was self-consciously arty and cerebral, deliberately esoteric and dysfunctional. Sure, a lot of them worked with groove-based black music, and had a lot of physical propulsion (as do a lot of post-step), but there was almost always a mind game element as well, they were never really "cutting loose" in the same way as 'nuum music and "pure" rock, funk or disco is, if for no other reason than it was always articulated, always subservient to some larger artistic goal (trance-states, confrontation, subversion, ritual).

Well, some might point out, doesn't goals like "confrontation" or "ritual" - even though they might be self-consciously constructed - show a strive for social energy and interaction, exactly the kind of thing that is lacking in post-step? And with that I would, at least mostly, agree. It just doesn't mean that post punk is "brock" music. Rather, it shows that social energy can take many other forms than just "getting your rocks off" on the dancefloor. I think placing post punk in the 'nuum would require a lot of creative shoehorning, but then again, I don't see any reason it should be there. Of course, it isn't straight up ethereal "brain music" either, there's still very much a physicality to it - if anything, I would say it's a part of both those worlds (and therefore not really belonging to any of them). And I would say it's the same with post-step. Which gets us to the second question.

Not only do I not have a problem with post-step not belonging to the 'nuum, it's even been one of my points all the time that it's the wrong lens to view it through. But does that mean that there's no visceral element to it, no "cutting loose" or "bursting-into-the-world"? Absolutely not. I must say that Reynolds inability to feel the visceral energy of post-step - and it does seem to have been a point of his right from the start - is really strange to me, because that was exactly what pulled me into it in the first place, what made me a believer. I did not - as suggested in the comments of the Energy Flash post - have to force myself to believe. What I did was accepting that here was something worthy of belief, without the safety net of post modern doubt and constant how-new-or how-good-is-it-really-questioning, saving me from having to defend what I love, and being ridiculed for claiming - how absurd, how naïve - that here is again something worthy of history. But I obviously wouldn't have accepted it if the music wasn't so overwhelming in the first place - and what overwhelmed me to begin with wasn't the more subtle and understated forms (of which there is many), because those are always easier to reject as "just more moody head music" - its originality doesn't demand your attention like the heavier stuff.

How anyone can listen to early poststep tracks like Slugabeds "Gritsalt", Suckafish P. Jones' "Match Set Point", or Eproms "Shoplifter", without getting blown away by the sheer physical force, the explosive energy, the visceral freshness, that is a mystery to me. After all, a lot of the first post-step (and especially what I've called bitstep) was pretty much a reaction to the challenge of wobble - not a "turning back" to "true dubstep" or neo-2step (aka funky), though there sure as hell were a lot of that crap too. Instead, the bitsteppers seemed to ask what the next step after wobble should be - how could you take this music even further out, make it even more mad and grotesque. It was pretty clear that it couldn't be done with just more convoluted twists of the wobble bass itself, the limit had been reached there (and as a result, big wobble producers moved into much more melodic, EDM-crossover territory), so instead post-step producers added cascades of multicoloured sound splinters, absurd syncopations and mangled structures, like treacherous vortices pulling you in several different directions simultaneously - and always with massive force.

The best bitstep delivered on wobbles promise, transforming it from a potential dead end to a gateway into a new world. And when it had opened my ears to the strange and wonderful new things going on, I discovered plenty of other forms of post-step that was equally unique and amazing, even though the brilliance wasn't as in-your-throat-energetic as with bitstep. Though indeed there weremany other forms of hyper-physical post-step too, sometimes even downright groovy (at least for a definition of groovy that includes something as weird as Can - as Reynolds' brockout list does) - the brutally twisted cyberfunk of Debruit and a lot of skweee had a massive, propulsive power, while the freaked out maximalism like DZA, 813 and Eloq is among the most over the top explosive stuff I've ever heard, and avant-trap like TNGHT, Krampfhaft and the later Starkey should be able to work a dancefloor as effectively as any classic rave music. Heck, despite being incredibly cold and dysfunctional, a lot of the current "cybermaximalism" (like Brood Ma, Wwwings and Amnesia Scanner), is also deeply visceral music.

So, I've proved my point then? After all, I've just claimed that a lot of post-step does indeed have a highly physical quality, bursting into the world with undeniable force, so obviously it does! Except... what do I base that claim on? On the fact that I feel it - to me it's undeniable. But to others, not so much, just like there's a lot of stuff that doesn't affect me the way others claim it should. And there's people who never felt rave music, or punk and post punk for that matter, found it empty and cynical, the surrounding subcultures destructive and pointless. In other words: if some music simply doesn't do anything for me, I know that this gut reaction isn't really an argument for it not being any good, I need some more objective way to measure it. But if that measuring device - say, how viscerally enticing it is - itself depends upon a gut level reaction, I'm back where I started. I guess this is why rock critics often use so much time on lyrics, more or less becoming ersatz literary critics, because words are slightly more concrete and tangible than timbres and harmonic structures. Perhaps the sociological angle used by many critics is useful in the same manner - giving them something "real" to deal with, and offering an easy measuring device: If music is worthwhile, it makes a socio-cultural impact - and if doesn't, it's not. Of course, by that standard you'd need some way to explain why, say, Celine Dion isn't more worthwhile than Xenakis or Sun Ra.

That said, this is indeed the point where I think something is lacking with post-step - it hasn't created an active, socially transformative (sub)-culture. That I agree with, but what I doesn't buy is that this is because the music in itself doesn't have what it takes to build such a social structure. A main point from my last post was that nothing could built something like that now, the social-media-mediated reality we inhabit makes it impossible, except as in the form of virtual subcultures, existing online, of which there's as many as you could wish for. They just don't have any transformative power. Or at least not the ones based on music, the physical manifestations of which - concerts, clubs, festivals - simply seem like extensions of the socially networked existence. I don't see any actual socially transformative musical subcultures going on anywhere, and I don't think it's possible anymore. Young people still go out, and a lot of post-step is indeed played at hipster festivals, where there's some social interaction and bonding going on. But no feeling of any chance of changing anything through music - or in any other way for that matter. The modern bohemians into experimental electronics - graphic designers moving from city to city in Europe and the US - might make enough to live sort-of-comfortably with this drugs-and-music hobby, yet they never seem to have any hope or dreams of achieving anything more than that.

Take grime - I think most would agree that the first generation had the shocking formal newness and the burning will necessary to create a truly powerful, reaching-beyond-itself subculture - and yet, it didn't really happen. Countless online 'nuum-connoisseurs clearly wanted it to be the next big thing, but it never got beyond cult status, and was first taken over by dubstep, later by the experimental second wave that seems to have given up all ambitions of moving beyond small, web based communities. In the end, I don't think any form of music will be able to be truly socially transformative in the world we currently live in, no matter how full of energy or how much it wants to. Had jungle never existed, and was then invented out of the blue today, I sincerely doubt it would have more impact than anything going on in post-step, or anything else. It could just as well be called yet another empty show of technical trickery with nothing expressed through it. Because if people are so desensitized that they're immune to the mad dynamics of the best bitstep, I can't see why jungles explosive rhythms should make a bigger impact. No matter how wild and physically powerful, if there isn't a receptive context, the social ignition isn't going to happen. And I think it's really the lack of this kind of "context" - a "practising community" (i.e "a way of life") grown organically around the music, and vice versa - that's the reason Reynolds doesn't relate to post-step. But then again, isn't this something we especiallyexpect from genres like rock, dance and rave? We don't usually diss the electro-acoustics for not having built a subculture of functionality and social practice around their music.

So where does that leave us? With a form of music which is as good as it's gonna get under the current conditions. And that is really, really good, as soon as you're able to accept that you're not going to get any kind of youth movement so potent that it actually makes an impact on society, as with rave and sixties rock. But you do get music that is an incredibly powerful reflection of our current conditions - and as such it's also music that is indeed having a lot released through it. Not pleasant things, mind you, but in its own way very true and overwhelming emotions. You could ask what the point of physically propulsive music is if people aren't going to use it in a social context. Now I'm not really sure this kind of post-step actually isn't used at some underground parties, but even if it's not, the viscerality is still crucial, because it reflects the psycho-somatic aspect of our supposedly purely cerebral online existence: the way it mangles our sense of time, place and identity, wears our body down and traps us in an everchanging maze of stimuli which renders us helpless and nauseas, the way the brightly coloured entertainment-fractal is simultaneously silly and terrifying, an exhilarating joyride with a sinister, insidious core of instability and uncertainly constantly lurking under the surface. To create this feeling, these strains of post-step do indeed need a to deliver a physical punch.

Now, I don't know how many of these producers consciously went for this reality-fracturing effect, for all I know they could just have wanted to create the sickest, most colourfully synthetic party music around, and then simply followed the music's logic all the way into the candy coloured nightmare zone. You can be a vessel for the zeitgeist without being aware of it. With the many strains of post-step that are more dark and atmospheric - directly revelling in the neurosis and hopelessness beneath the surface - the feeling of disintegration and entropic decay often seem to be a much more conscious thing, descended from the whole "death of rave"/end of history-discourse around Burial. Here, the lack of visceral force is part of the whole point of what is being expressed. Its impact is purely on the emotional level - but it's certainly still there, at its best as strange, disorienting and sometimes downright spellbinding as any, say, Young Marble Giants, Tuxedomoon or early Cabaret Voltaire. Which again brings us back to post punk: Unlike rave and sixties rock, post punk and post-step doesn't express a victorious belief in owning the future; rather, it's the sound of desperate resistance against a world where the very possibility of hoping for a better future is being increasingly crushed.

With post punk the resistance could still - and indeed, mostly did - happen through physical social interaction. With post-step it has moved to the virtual sphere, and the "resistance" is happening almost entirely on the art-for-arts-sake level. Some might say that isn't much, but considering that current music is not supposed to be able to do more than mix and re-contextualize pre-existing elements, that art is simply seen as a vehicle for tastes and opinions, I'd say it's actually incredible that something as original and overwhelming in its distillation of the zeitgeist is even existing. Never alone in the soul-destroying web of constant social media, yet isolated and paralyzed, people still dream of strange new worlds never heard before, still want to invent thrilling, absurdly twisted musical structures even if they seem to have no "purpose", still manage to create ominous musical forms that capture the essence of the very condition that should render them incapable of creating anything of any relevance at all. That such a wealth of invention is still possible, still being made, despiteall the forces opposing it (including the creators doubt in their own relevance), well to me that's at least as amazing as people coming up with good stuff under deeply fertile conditions. That stuff as inventive and vibrant as the best post-step mange to even exist now seems like an act of defiance. That it's one of the only places where I can still feel the spark of creative resistance - in a way, relevance - is all the more reason to cherish it. But of course, you'd have to be able to feel that vibrancy, otherwise, well...

After all, what do I know - to me most contemporary rap is completely pointless and with as much relevance and "promise of freedom" as contemporary metal. Or musicals. All something that command social energies and make a lot of people feel something on a gut level - just not me.

...

I think this is going to be the last post-step piece of mine for some time. Have I exhausted the subject? Well, on the level of these long think pieces then yes, I guess I have - even if I still feel like elaborating, I'm already starting to repeat some things from last time. But I'm not exhausted with poststep. Sure, as for new releases, 2017 hasn't been impressive, and I suspect last year was simply a last spasm, or perhaps even the beginning of a different, more static era. Yet, I'm still listening to the older post-step records almost all the time, still not tired of it. So, what I'd perhaps like to do is to go more into some of my favourites, trying to - to use Reynolds' term - incite, making the greatness and expressive power of the music directly relatable, rather than arguing its relative newness in the larger historical context, as I've mostly been doing so far. I have a half baked theory that the lack of messianic writing about specific tracks or records is at least a part of why it's impossible to create the same level of excitement about new music as in previous eras. Back then, when it could take a long time before you were even able to listen to a reviewed record, inventive descriptions in good music writing became a part of how you heard the music, part of its greatness - sometimes the music couldn't live up to the incredible imagery, but ideally, the writing made great music even better, made you hear it in a way that convinced you of its greatness. Now, all you get is a bunch of youtube clips that you'll skip through, unimpressed. I don't think any real incitement can happen that way. I think "forcing" people to use their imagination about music makes that music more vibrant, and makes the relationship with it deeper. So that's what I'll try to do, perhaps, some time. For now, though, I need a break from thinking about post-step (if not from listening to it), and I've had one or two other things lined up for a long time, before I suddenly got caught up in this whole post-step thing, so perhaps it's time to look at them.