20-Feb-18

Whilst the New Year may be open to question the quality of the work on this album is not. Furthermore, you're invited by the label to make your own additions to these tracks, the first layer 'is created within the collaboration of MƩCHΔNICΔL ΔPƩ and Les Horribles Travailleurs', so the challenge is set, although this is very much in the spirit of collaboration rather than competition. As always, the bar is set high here but why not (re) create? Remake/remodel (should be a Roxy Music title...oh, it is?). 'You are invited to finish this soundwork by altering\adding layers etc. to the first layer, which can be downloaded from Bandcamp'. As it stands it's very good.

09-Jan-18

Let's start the New Year with a whimper...@',mn,mn,qwwwwwhhhhhhhhherrrr'

Fact is this year's going to be the one that sees the downfall of the music industry due to it's incessant gnawing of itself like a doped-up rabid labradoodle, foaming as it very slowly chews its own leg off and keeps going as far as it can reach until it's stinking innards spool out across everything but don't worry, you will be immune to the putrid, poisonous substance due to years of injecting the antidote in the form of JS Bach, James Brown, Bernard Parmegiani and other names involving capital 'B', or 'L', or 'D'...how about 'D'? Don Cherry, Defunkt...that's enough, that's the ABC of it, your alphabetically registered pantheon of ....music people...the countermeasure to all the crap...

On the subject of letters...

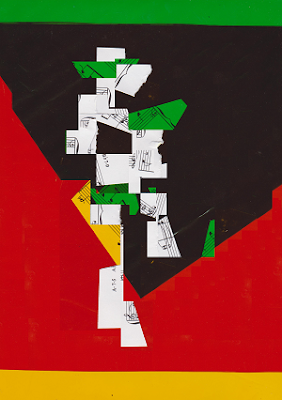

That one's called AB...there's more of my art over here

Whatever...or, actually, all my art work this year will be part of a series called So What...why? I reckon it's the most common response.

In 2018, though, let's not be blase about things, least of all what we love the most and what we make...

01-Jan-18

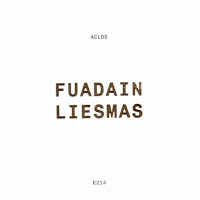

Under the radar, off the map...such terms hardly do justice to Chris Douglas' non-place in the what we might call 'the music world', even the 'underground electronic' version. No surprise then that Fuadain Liesmas has not, to my knowledge, appeared in any end-of-the-year charts. As Dalglish, O.S.T. and Scald Rougish, Douglas has persisted in making music for any reason but the desire for publicity or, perhaps, praise. Not that I believe he wouldn't welcome recognition. Searching for reviews of this album I've found no mention other than on this blog and, of course, Boomkat (because their job is to try and sell music).

Describing the carefully crafted sounds here would be a challenge for most would-be critics, yet that's no reason for it's apparent invisibility; many writers are better equipped than me to talk about 'abstract' sound and do so regularly. Nonetheless, here I am...on the edge of...reviewing what eludes easy categorisation.

Negin Giv, being just 30secs long, might be a good place to start (and end?) since it is, in microcosm a snapshot of Douglas' methodology....his ability to...punch holes in ...the space-time continuum...? If I improvise, forgive me. Free-flowing word scrambles might suit talk of Jazz, but Fuadain Liesmas being so meticulously composed I feel duty-bound to attempt the same in writing. And fail.

OT-IntVxEs 1 is typical of what goes on here, which is not to suggest that it's all predictable from the outset (only in...approach to sound). Rather, I mean, in creating melancholic (?) tones which in other hands would signal mere ambient eternal drift somnambulism, Douglas scatters brittle components throughout. No sleeping here. No daydreaming 'bliss'. Only on Hrm Clng or Dtn#09_Ed do we find what feels like a place of rest, albeit one derived from an afterlife (?). After what? This is life, in all it's restless, skittish, uncertain gravity.

Perhaps ambiguity renders such albums unpopular; not 'difficult listening' - that, surely, is in the ear of the beholder. Albums that gain attention often shout something, even if in a thoroughly minimalist, quiet fashion. Is the popularity of Ambient a result of what many perceive to be a politically turbulent world? An escape from that madness? As if the world has ever been stable. Whatever, the thing to do is make music which speaks of either 'the street', or technological trickery in the service of an adrenaline boost. Songs, naturally, are always in favour. Fuadain Liesmas offers no such musical certainties. It's neither flash nor pleasingly serene. Ultimately, I can only say 'It is what it is'. You can get a taste from the stream below, but to fully savour what Chris Douglas has created, I suggest you buy the CD from here.

26-Dec-17

RTomens, 2016

WHAT? forgive me. I dunno. WHEN? last year. I mean, this year, 2017. In PC world nobody's memory works so I must consult this blog, scroll back in time (one day everyone will have mental bookmarks implanted, won't they?) to see which albums might be consideredmemorable worth mentioning in a round-up...

So here goes...

Broken Ground - Christian Bouchardreview

Structures And Light - Group Zeroreview

Sacred Horror In Design - Sote review

Mnestic Pressure - Lee Gamble

review

Some People Really Know How To Live - Shit and Shine

review

Hesaitix - M.E.S.H

review

Fuadain Liesmas - Aclds

review forthcoming

Monika Werkstatt - Various

review

A Little Electronic Milky Way Of Sound - Roland Kayn (this didn't even make the Wire charts!?)

review

Entertaining The Invalid - Various

review

12-Dec-17

Texture, abstraction, atmosphere...mood music for the apocalypse in your head. Who is not enduring small (or large) psychotic trauma on a daily basis? It's the modern world...in which other modern people go about their business, answering 'it' with just a 'sigh'.

COMA †‡† KULTUR

Pay what you want but somehow you will pay it all, (play it all) back...

08-Dec-17

All The Marks Of Identity Are Swept Away, RTomens, 2017

Wonder why...I'm not myself of late...

Self-Portrait, RTomens 2017

STARVE LIVING ARTISTS INTO SUBMISSIONDO NOT SHOP

06-Dec-17

Art: Monk's Mood - Tribute To Thelonious Monk [ 06-Dec-17 6:14pm ]

Art: Monk's Mood - Tribute To Thelonious Monk [ 06-Dec-17 6:14pm ]

RTomens, 2017 Three art works from a series I made in honour of Thelonious Monk. The music is taken from his tune, Monk's Mood.

RTomens, 2017

RTomens, 2017

30-Nov-17

So another CD chariddy shop bargain, Cypress Hill's Black Sunday for a quid - whoo-eee! I had this on vinyl too when it came out - then - what happened?

Remember when hip-hop was big? Remember when Public Enemy were fresh after the old first wave - like dangerous music, like grabbing the torch from The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron bad - eh? Yes. Then, well, not quite then, but a few years after the second wave, maybe even the third, hip-hop got out of control worldwide MASSIVE - didn't it? Like many a street sound before it soon every square on the block was into this thing whilst debates about how good it was for the black community and folks at large, what with all that swearing, cop-killing, female-disrespecting, money-idolising, gang-glorifying lyrical splurge - all of which only endeared it to youth and gangsters, naturally. The bigger hip-hop got, the smaller my interest. What this says about me may be that I'm a snob who reacts against popularity, or simply prefers movements when they're fresh? What? Which?

Here's an album that went Triple platinum in the U.S - fuck! I knew Cypress Hill were popular but...only just saw that stat on Wikipedia. I remember loving Black Sunday when it came out, like millions of others - it had the juice - got the juices flowing - but that was then - how would it sound 24 years later? How about BRILLIANT! tHAT'LL DO. sHOCK. tHERE WAS ALWAYS SOMETHING ABOUT b-rEAL'S VOCALS THAT WERE DIFFERENT AND STILL SOUND THAT WAY, AS IF HE'S PERMANENTLY, YES, INSANE IN THE MEMBRANE AND HAMMERING AT YOUR WINDOW TO TELL YOU ALL ABOUT IT. Whoops, caps lock - which rhymes with 'Glock, funnily enough.

In retrospect it's easy to hear how Cypress Hill got so big and so rich. The samples are choice, the mixing is absolutely perfect with the breaks in your face and somehow this album insists that you succumb, not through lyrical force so much as vocal/rhythmic dynamism. It's not original (when did that ever get you rich?). If anything, it's stereotypical of hip-hip subject matter (violence, drugs, bragging) - yet - yet - after the first four tracks you're slaughtered! Putty in their hands. Well, I was, again.

29-Nov-17

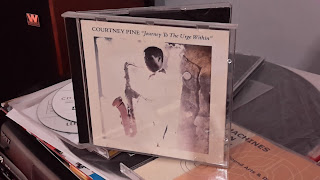

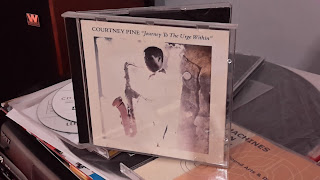

Courtney Pine's debut album for a quid? Couldn't resist. Of course I owned the vinyl when it came out, which was 1986...and Courtney was our Coltrane - he was! We could only watch in awe as our man, a young black man, in a suit, delivered his version of what was then contemporary Jazz..in London Town! He was slimmer then - we all were. He was also the only one to make the cover of the NME. Well how has it aged? Fine, to my surprise. As We Would Say sounds particularity good. OK, in the writing stakes he was no Wayne Shorter or Coltrane, but after 31 years and in the context of all that went before Journey To The Urge Within holds its own with no small help from the likes of Julian Joseph on piano, Gary Crosby's bass and Mark Mondesir's drumming.

So today I came across an interview Pine conducted with David Bowie in 2005, asking him about the influence of Jazz in his life. Turns out our David had some impressive names to drop. I'd never heard Bowie talking about Jazz before but I've often wondered if he got the 'Wham bam thank you mam' line in Suffragette City from the Charles Mingus track. It's more likely he nicked it from the Small Faces tune of that name, of course.

To continue the Mingus connection, when asked for the one Jazz tune that really moves him, Bowie goes for Hog Callin' Blues from the album that Wham Bam Thank You Ma'am was also on, Oh Yeah. A man of taste! This also happens to be one of LJ's favourite tunes. Just listen to Roland Kirk tearing the roof off the studio...

28-Nov-17

Pure (sun sound) pleasure from Modern Harmonic and how clever of them to collate Sun Ra's 'exotica'. For those not familiar with Sun Ra any sampling of tracks from here will be a surprise if they had him down as too 'crazy'. They may even wonder what all the fuss is about but to miss Ra in these moods is to ignore their worldly 'ancient' and thoroughly justified inclusion in the Arkestral sound collage. Essential.

Accelerated Destruction, RTomens, 2017

This along with other art prints is available now in my shop

22-Nov-17

How much more 70s/80s cassette culture can we take? - loads! it seems. And why not? There's much pleasure to be had from the beneath-the-underdog bedroom synthesists; the chancers, non-game- changers, radical visionary lunatics and nerds with attitude.

'Nuclear fuel breeds nuclear war/The politics of power/ Rotten to the core' - it's Missing Persons and Rotten To The Core, one of the treats on this superb collection, which illustrates many angles taken by the Lost of Tape Land. PCR's Myths of Seduction and Betrayal (Extract) is another gem. Human Flesh, Urbain Autopsy are names that tell of the Cronenbergian body mutation fixation of the times, when perhaps the recently-evolved opportunity to integrate mind and machine bred obsession with cybernetic mutation. Who knows.

Cassette-sharing sites are popular now but for obvious technical reasons the sound quality is usually poor so this is a welcome chance to hear hi-resolution lo-fi emissions from the vast cavern of underground cassette culture.

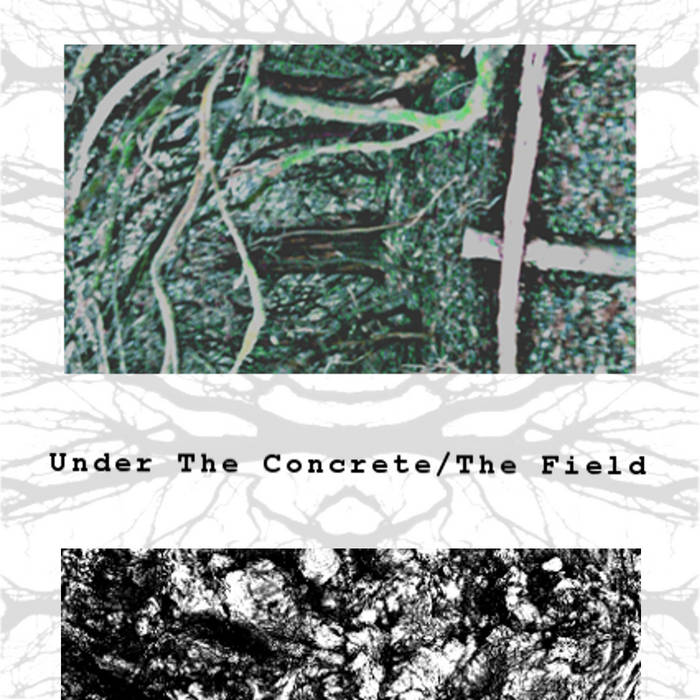

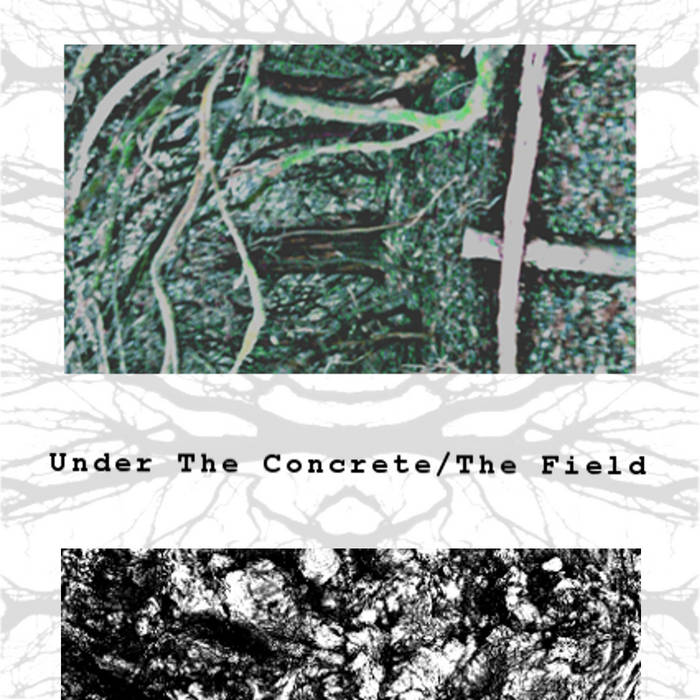

Beneath the concrete field, the beach? Perhaps not. Here, at least, is a contemporary collection worthy of your attention. Material by Mark of Concrete/Field, remixed by various folk, most of whom have remodelled original sounds in a very interesting way. Descent's Freebase has great depth, a build-up of tension pressure that's all the better for never actually being released. AMANTRA's Scorched Earth Policy wouldn't sound out of place on the Underground Cassette comp - I mean that as a compliment. Kek-W got A Fax from Philip Glass (great title), well, I suppose a few people did in the 80s - anyway, as always, KW's work is spot-on/interesting, as is Libbe Matz Gang's Tratamento de Enxaquecas, like death metal machine music! Very good comp.

Windows To The SoulBEFORE I GO, A PLUG FOR MY ART PRINTS, WHICH ARE NOW AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE HERE

21-Nov-17

Oh, yes, it's Ladies' Night

And the feeling's right

Oh, yes, it's Ladies' Night

Oh, what a night (oh, what a night)...

...Monika Werkstatt at Cafe Oto - yes, what a night! You don't need me to tell that electronic music is a male-dominated world (which part isn't? bingo?), just like Rock, but unlike that traditionally macho realm of phallic axe-wielding at first glance there should be no reason for electronic music being a (mostly) men-only domain, until you start thinking about stereotypical male gadget obsession and the historical culturally-enforced tradition of DIY (inc tinkering with electronics).

Issues surrounding all that (not bingo or DIY) were discussed in the Q&A. An interesting point was raised about how women are expected to be 'brilliant' whereas it's OK for men to be 'all right'. The conclusion was that women should be allowed to be 'all right' too. The issue of expectations aside, pure percentage stats dictate that there's a lot more average male performers in electronic music simply because they dominate.

Politics aside, if it's possible to lay them aside and see the performers as just that (perhaps there's an irony there in rightfully demanding equality, ie not just being viewed as 'female artists', whilst presenting an all-female collective - tricky) with nothing to prove Monika Werkstatt proved it. It was an evening of seductive, passionate, humorous, powerful music, each of the four players performing two songs before a collective session finale. All four were present on stage throughout and it was entertaining just watching their individual reactions to what the performer was doing.

Before the collective, support came from London's La Leif, who brought beats and bass fit to shake Cafe Oto's foundations with a very tough set.

The first of MW to perform was Sonae, whose subtle, richly-textured ambient sounds set a good tone...

Then Barbara Morgenstern ('Queen Of Harmonies') delivered two superb songs, the power of which was amplified times 10 in a 'live' context...

Watch out, it's Pilocka Krach, surely the prankster in the pack, giving us all a good slap with her stomping Electro-Power-Pop! Do you like the beat? Yes, I did!

Finally in solo form, 'the boss', Gudrun Gut, organiser of the whole collective and legendary figure on the scene for years.

The quartet session was as intriguing as you'd expect from four diverse artists with their very own styles, working together intuitively, in the spirit of improvisation, just don't call it 'Improv', Gudrun's ambiguous about that scene and I don't blame her. As she said, it's something you can hate yet be drawn to at the same time. There's nothing to hate about Monika Werkstatt. Do check the collective album. It's an essential release from this year. As an encore, the joint was jumping to Who's Afraid Of Justin Bieber? Here's a brief video I took...

Oh what a night!

20-Nov-17

Improvising to tape loops may sound implausible, or rather, contrary to the spirit of Improv, but who cares about that, eh? Not you. So here's saxophonist Colin Webster doing just that and the combination of his chops and repetitive sounds works very well. You can almost hear Webster thinking 'What shall I do with this?' in the unaccompanied sections, which adds to the intrigue. Being capable of creating many varied sounds from his horn, Webster has no trouble finding the 'right' tone for each loop (well, perhaps he did, but the released versions all succeed).

On impulse I called in Daunt Books today to see what sci-fi they had. I asked the girl if they had a section for it, she said they didn't because they 'specialised in travel'. "What about space travel?" I asked..."I know," she replied, almost smiling...

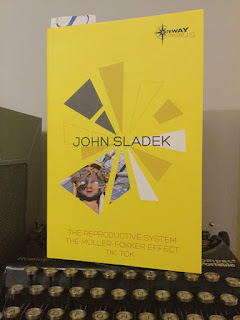

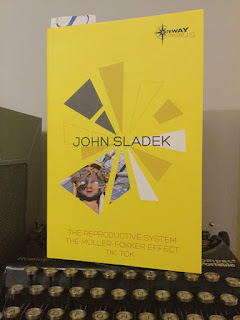

Bought this John Sladek collection the other day, having decided to read more science-fiction. The genre has promised more than it's delivered as far as my needs in recent years are concerned. Those needs have changed since I started reading sci-fi a long time ago, of course.

After the early-teen experience of space adventures I progressed to the biggies such as Asimov and co.. It wasn't until the late-70s and discovering William Burroughs that my view of the genre changed completely; in short, he ruined it regarding everyone else, except JG Ballard, who I still rate highly and read regularly. That's no coincidence considering Ballard's opinion of Burroughs despite their very different writing styles.

Burroughs even gets a mention on page 79 of this Sladek collection from a stoned character trying to get to Morocco. Published in '68, the first novel, The Reproductive System, reflects the era in a good way rather than a 'dated' fashion, covering paranoia, anti-authoritarian, secret agent, science-gone-mad cynicism in the spirit of adventure that reminds me of both Michael Moorcock's Jerry Cornelius and Wilson and Shea's Illuminatus! Trilogy. So far so good and since I will finish it that's a recommendation from someone who's a serial non-finisher (life's too short, isn't it?)

TTFN

19-Nov-17

Space Age print / Flying Saucers Are Hostile / Starship Troopers / Shit & Shine - That's Enough / Felix Kubin - Takt der Arbeit [ 19-Nov-17 3:37pm ]

Space Age print / Flying Saucers Are Hostile / Starship Troopers / Shit & Shine - That's Enough / Felix Kubin - Takt der Arbeit [ 19-Nov-17 3:37pm ]

RTomens, 2017

More of my art here

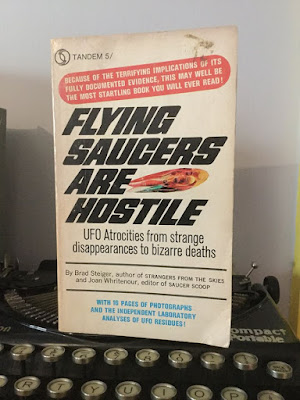

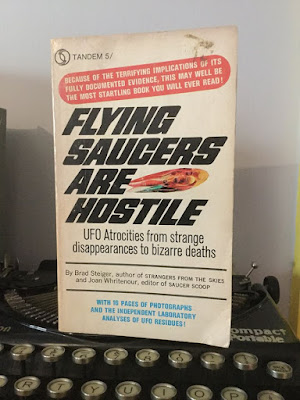

1967 1st edition

You've been warned - 'YOU DARE NOT ALLOW YOURSELF TO IGNORE IT!' (from the back cover).

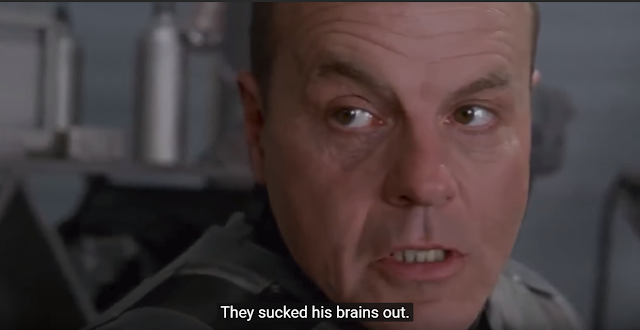

Flying saucers are hostile, so too are the alien bugs in Paul Verhoeven's Starship Troopers - "The only good Bug is a dead Bug!". It's 20 years old and re-watching it I confess to enjoying it even more than the first time. That's a 'confession' because revelling in a film filled with square-jawed, squeaky clean heroes out for military death or glory to bombastic soundtrack sounds like hell as a film, but that's the point. ST is pumped up and primed as a trashy action film whilst constantly undermining everything it superficially celebrates. It's very sheen is as sickening as the site of a bug ripping a soldier limb-from-limb. It's gung ho writ large but gets booby trapped at every turn. Verhoeven knew what he was doing but did it so well that few could see the subversive irony through all the flying limbs and phoney machismo.

In a way Shit & Shine like to play with machismo (note the cover) - perhaps they really are macho men. But there's an 'ironic' edge to most everything they do and their latest, That's Enough, is no exception - 'Do you know the way to the garden party?' - the EPs filled with samples, a long one opening the opening title track, which you've probably heard by now. The Worst continues playing with the sample idea - the judges on American Idol? Subversion, like ST, is embedded in the per-usual nasty grooves - that must be Simon Cowell sampled - we might think that's enough of that talent contest shit but it just seems to keep rolling and so too, thankfully, do Shit & Shine.

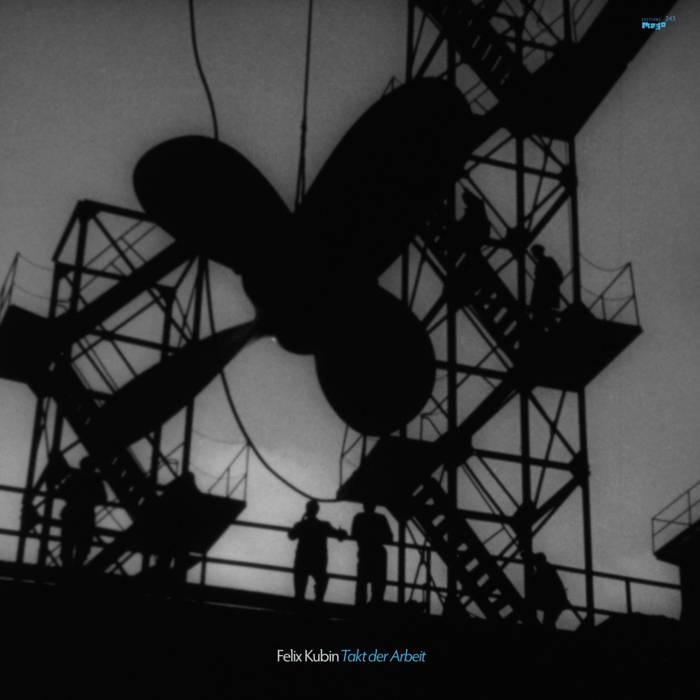

Do they still make musical geniuses? What do you reckon? Whoever 'they' are - parents of musically gifted kids who rise above being mere talented? What? Anyway, Felix Kubin: as Mark E Smith said 'Check the guy's track record' - it's impressive, to say the least. Here he is with Takt der Arbeit, four soundtracks to educational and industrial 16mm films about work. Is this a return to the fascist/imperial/dictatorship reflected in Starship Troopers? Is that what Work is?

Track one has a militaristic slant (those drums) echoing the regimentation of both machine and human operators but here Kubin brilliantly orchestrates the components into something that sounds part friendly info film soundtrack, part chaotic depiction of factory-frazzled minds. Geburt eines Schiffes has the mood of Soviet-era proletariat-powered propaganda so strong you can see the workers marching towards you over the horizon, shirt-sleeves rolled over bulging biceps. Hold on, I got carried away with that idea. The actual mood is one of a huge industrial-age factory gradually coming to life with the roar, clank and hiss of machines complete with triumphant music heralding the brave new era of man-made mechanical wonders - or hell, since the overriding atmosphere is actually one of foreboding and tragedy. Martial Arts continues the work-til-you're-musclebound theme but Kubin continually breaks things down (a musical spanner in the works). The group Kubin works with add essential components to the EP; the human element in what could have been just another 'industrial record' in other, less creative hands. Release date was supposedly Nov 17th but as I write it's not yet out so keep an eye on Editions Mego. Don't miss it.

17-Nov-17

Briggflatts by Basil Bunting is one of the great poems of the twentieth century. However, it has not always occupied a prominent place in discussions of modern poetry. The reasons for this are complex, and have largely to do with a range of contentious biographical and historical factors (such as the marginal status of modernism in the UK and Bunting's own variable reputation). Another factor, the poem's supposed difficulty, requires some qualification. Briggflatts is a dense, carefully wrought high-modernist work. As with other poems in this bracket (The Waste Land, The Cantos, The Maximus Poems) it repays diligent close reading and re-reading. But it is arguably more vital (and, dare I say it, accessible) than those works, and can in fact be appreciated pretty well by first-time readers. As a teacher of undergraduate students over the last few years, I have found that Part 1 in particular lends itself very well to group reading and seminar discussion: indeed, the first section of Briggflatts seems to me to serve as a far better introduction to modernist poetry in a pedagogical context than a work like The Waste Land, with its copious and contested layers of allusion. It does help, it is true, to have a skeleton key to unlock some of the key features of Briggflatts. But I think the really essential facts about the poem can be summarised in a relatively modest space. The following brief guide to the poem should hopefully provide a good foundation for first-time readers. I have tried to shine light on the basic subjects and structures of Briggflatts, without diminishing its music and magic.AN, 2017

Part 1

Season: Spring

Phase of Bunting's life: Childhood

Location: Northern England

Part 1 is the most immediate and tightly structured in the poem. Twelve stanzas, each of thirteen lines, sketch an idealised panorama of Northumbria (in Bunting's poetic vocabulary this meant pretty much the whole of Northern England). The verse here is emphatically musical, foregrounding alliteration, assonance and internal rhyme, with a stark rhyming couplet at the end of each stanza to draw it to a close. In one sense, this is pure sound evoking a pastoral idyll and it should be enjoyed as such: Bunting himself said that readers (or listeners) shouldn't try too hard to uncover 'meaning' beneath the musical surface of his verse. At its simplest, this whole section is an extension of the song of the bull ('Brag, sweet tenor bull') in the first line.

However, that is not quite the whole story; there is also a definite realist narrative here. Bunting is recalling a childhood 'holiday romance' with a girl called Peggy, which took place in the early 1910s in Brigflatts (the correct spelling), a tiny village in the North Pennines. Rawthey is a river; Garsdale, Hawes and Stainmore are nearby locations; the stonemason and miners are local characters. Part 1 is therefore the beginning of a process of remembering real things, literally the first chapter in an autobiography. Deeper history also comes to the surface with the first, brief appearance of the Viking warrior and sometime ruler of Northumbria Eric Bloodaxe, killed in battle on Stainmore around 954AD. This enigmatic darker image or 'tone' prepares the way for the mournful conclusion to part 1. Spring ends, the natural presences begin to die and rot, and somehow—we never quite find out why or how—the poet's idyllic love affair with Peggy is 'lain aside' and forgotten.

Part 2

Season: Summer

Phase of Bunting's life: Early adulthood to early middle age

Locations: London; North Sea; Italy; North Pennines; Middle East; Mediterranean

Part 2 is by some distance the longest in the poem. In stark contrast to the chiselled stanzas of part 1, part 2 is an eclectic collage of clashing poetic fragments, perhaps intended to mirror the immature, evolving state of Bunting's mind throughout his wandering 20s and 30s. We start with an intentionally dramatic change of location, from the idealised North to artificial, money-obsessed London (Bunting is nodding at similar depictions of the capital in Wordsworth's Prelude). From this point onward there are continual geographical shifts (again, this is a recollection of real events in Bunting's early life). We are treated to a short tour around 1920s Bloomsbury bohemia (lines 1-23), a jaunt along the Italian coast and mountains (most of the middle of part 2 from 'About ship! Sweat in the south') and finally to a more obscure conclusion that includes flashes of the Middle East, where Bunting spent the latter part of World War II ('Asian vultures riding on a spiral column of dust') and generalised Mediterranean references—as well as spending the early 1930s in Italy, Bunting returned there during and after the war as a soldier and intelligence agent. In between these biographical fragments, more indirect passages and mythical subjects jostle in typical high-modernist fashion. The Bloodaxe narrative is treated more fully: we see Eric cruelly commanding a longship in the North Sea ('Under his right oxter …') and then dying a horrifically violent death back in the Pennines in the first great climax of the poem (the long passage beginning 'Loaded with mail of linked lies'). Paralleling this episode, Bunting nods in the final lines of the section at the Ancient Greek myth of Pasiphae, who gave birth to the Minotaur after an encounter with a bull sent by the sea-god Poseidon (note the subject rhyme with the bull at the start of the poem).

As well as being a sometimes chaotic—though often beautiful—record of the frustrations of Bunting's early adulthood, part 2 is also the place where the underlying moral of Briggflatts is first advanced. Put very simply: human beings cannot control the world, they must find a way to co-operate and co-exist with it. As Bunting put it (far more eloquently) in his 'Note on Briggflatts': 'Those fail who try to force their destiny, like Eric; but those who are resolute to submit, like my version of Pasiphae, may bring something new to birth, be it only a monster.'

Part 3

Season: n/a

Phase of Bunting's life: n/a

Locations: Edge of the world; Northumbrian arcadia

Part 3 is outside the main structure of the poem: it refers neither to a season nor to a specific period in Bunting's life. Nevertheless, Bunting intended it to be the climax of the narrative. In musical terms this is the 'loudest', most forcefully expressed part of the poem, the place where the moral first hinted at in part 2 is affirmed in a dramatic 'big reveal'. The section is based on an episode from the medieval Persian epic poem Shahnameh, which includes a portrayal of the Greek leader Alexander the Great (356-323BC). In Shahnameh, Alexander journeys with his troops to the mountains of Gog and Magog at the edge of the world. At the summit he leaves his men behind and encounters an angel (Bunting has him played by the Biblical figure 'Israfel') who is poised to blow a trumpet to signal the end of the world. There is some ambiguity in Bunting's retelling of this legend. What exactly happens to Alexander on the mountain? Why does Israfel 'delay' in blowing the trumpet? What sort of divine intervention is at play here? Yet the underlying moral is clear. Alexander tries to conquer the world and reach the limits of experience, but in doing so he is ultimately returned back to the ground, to his homeland (for Alexander this was Macedonia, but Bunting describes it here as a kind of Northumbrian arcadia). Lying dazed in the moss and bracken after his fall from the mountain, he encounters the hero of Briggflatts, the slowworm (actually a snake-like lizard) who advises him to lie low, be patient, persistent and mindful of the beauty of his surroundings.

This is the most abstract moment in the poem, but there are also clear parallels here and throughout part 3 with Bunting's biography. The opening passages of the section caricature greedy, powerful people who obstruct creativity and make life a literal shitty nightmare. As a struggling poet for much of his life, Bunting had built up some resentment towards these establishment 'turd-bakers', such as the businessman and newspaper owner Lord Astor ('Hastor'). The overall narrative shape of part 3 also mimics the curve of Bunting's middle years: after spending much of the 1940s in Persia (poring over works like Shahnameh) he returned in the 1950s to Northumberland, the homeland from which he would eventually write Briggflatts.

Part 4

Season: Autumn

Phase of Bunting's life: Late middle age

Locations: North Yorkshire; Lindisfarne; Tynedale

Part 4 is the shortest section in Briggflatts, and is best viewed (or heard) as a penultimate, minor-key movement resembling those in pieces of classical music (Bunting called Briggflatts a 'sonata'). You don't need to follow this musical analogy too closely, but it might be worth spending some time looking at the way Bunting weaves together different textures and 'themes' in the second half of part 4.

Aside from its musical properties, part 4 is also notable for its elegiac subjects. It begins with allusions to the sixth-century poet Aneirin (the correct spelling), whose most famous work Y Gododdin describes the Battle of Catterick and its aftermath in North Yorkshire around 600AD. The purpose of this allusion is twofold. Firstly, Bunting is nodding at what is in effect the first Northumbrian poem (although Aneirin was a 'Welsh' poet, we should remember that the Welsh or Britons lived in Northumbria prior to the Anglo-Saxon arrivals of the fifth and sixth centuries). In terms of the realist dimension, there may also be a glance here at the war and destruction Bunting witnessed in the mid-twentieth century (we are now, chronologically, up to the 1940s-1950s). More personally, the litany of death and decay segues eventually into a recollection of the lost love affair with Peggy. In some of the most moving lines in the poem, Bunting says 'goodbye' to his memories of Peggy as he settles down to lonely old age in post-war Northumberland.

But there is some light in the gloom. Aside from the redemptive music of the baroque composer Domenico Scarlatti, we also encounter the Northumbrian Renaissance of the seventh and eighth centuries (a dramatic 'rebirth' following the violent period marked by events like the Battle of Catterick). Among other achievements, this cultural upsurge produced the Lindisfarne Gospels (celebrated in the gorgeous passage beginning 'Columba, Columbanus …'), a beautiful illuminated book created in part to celebrate the life of the Northumbrian saint Cuthbert, who appears here as the (positive) mirror image to the (negative) portrait of Eric Bloodaxe in part 2. Aside from his Northumbrian pedigree, Bunting gives Cuthbert a starring role because he reputedly 'saw God in everything'. In line with the moral of Briggflatts, Cuthbert was a quiet hero living on the margins of society who loved nature without seeking to control it.

Part 5

Season: Winter

Phase of Bunting's life: Old age

Locations: North Northumberland, Farne Islands

If part 4 was mostly tragic notes with a brief major-key interlude, part 5 is the opposite. Like the final movement of a symphony, this is a resounding conclusion to the poem ('years end crescendo') although it ends with a sad diminuendo.

In musical verse that often recalls the 'Sirens' episode in Joyce's Ulysses, Bunting revisits the idyllic landscape of part 1 (the powerful opening syllable 'Drip' recalls part 1's 'Brag'). But now that he is an old man the perspective is different. We have moved from the mountains in springtime to the Northumberland coast in winter, where the sea speaks of finality and the end of a journey. Having accepted the need to be patient and respect human limitations in the face of nature, it is now possible to appreciate the precious details of life: rock pools, a spider's web, the lapping of the ocean, the way birds fly in harmony, the skill of shepherds in handling sheep dogs, the inexplicable wonder of the night sky. There is a kind of spiritual idealism here, and this conclusion is certainly upbeat and effusive in some ways, with the faint suggestion of a happier ending to Bunting's life than was predicted in part 4.

Part 5 is on the whole concerned with images in themselves rather than any more complex symbolism, but the line 'Young flutes, harps touched by a breeze' may just carry a hint of the optimism Bunting felt in the mid-1960s, when he was 'rediscovered' by younger poets and finally became a celebrated literary figure. However, there is still the nagging sense of tragedy that has persisted throughout Briggflatts. As the stars shine out over the Farne Islands, where St Cuthbert once lived and worshipped, Bunting remembers Peggy for the last time, and awaits a final 'uninterrupted night'.

Coda

The Coda is a fragment composed prior to the rest of the poem, which Bunting rediscovered and welded on at the last minute. It is a condensed summary of the key philosophical motifs in the previous sections: the power of music, the impermanence of all creation, the impossibility of knowing everything. Tellingly, the poem ends with a question mark (this is a work of literature that proclaims its own uncertainty and inability to conquer the world with language). For all that, one thing is certain in the end: as Bunting once remarked, Briggflatts is 'about love, in all senses'.

15-Nov-17

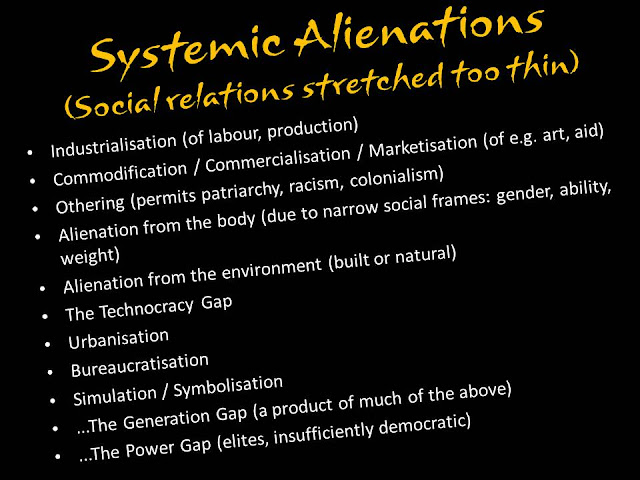

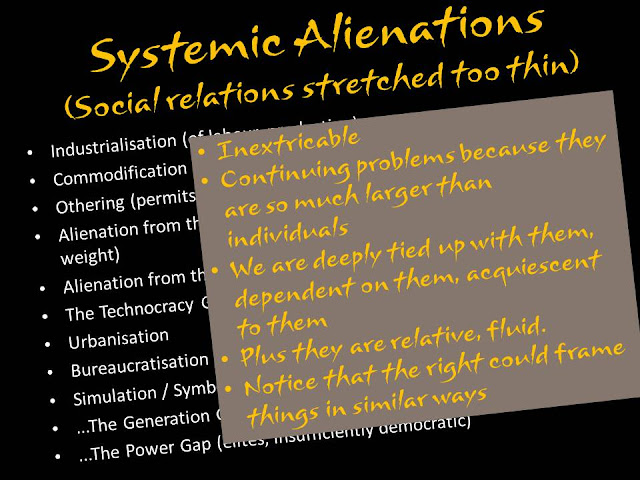

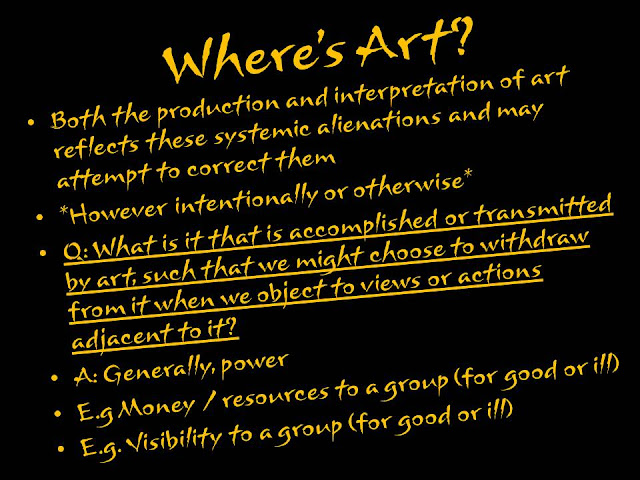

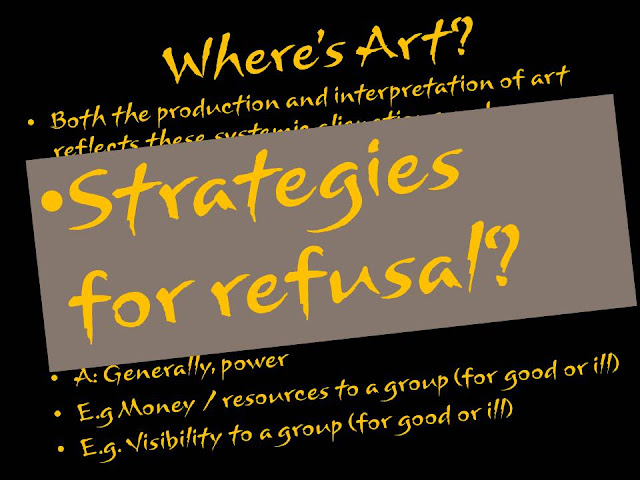

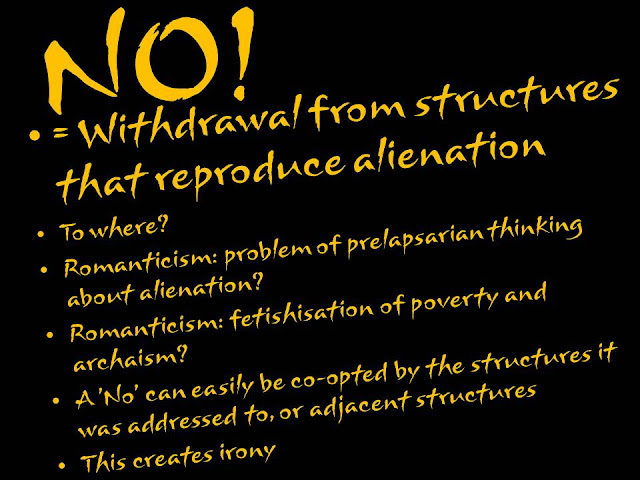

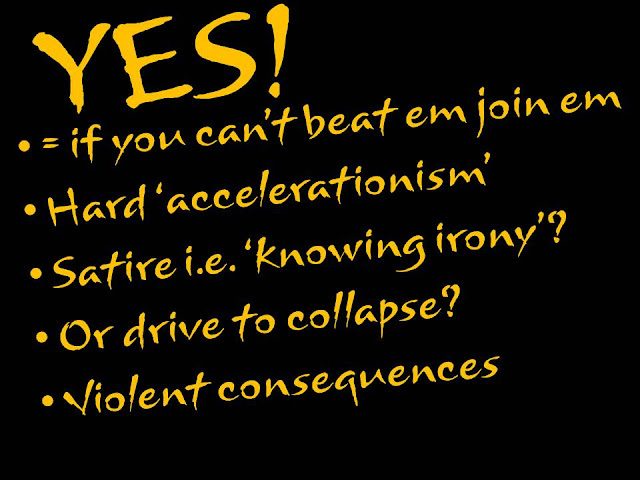

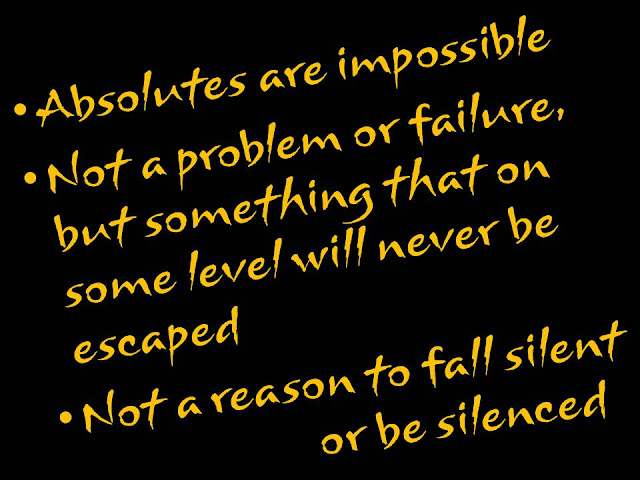

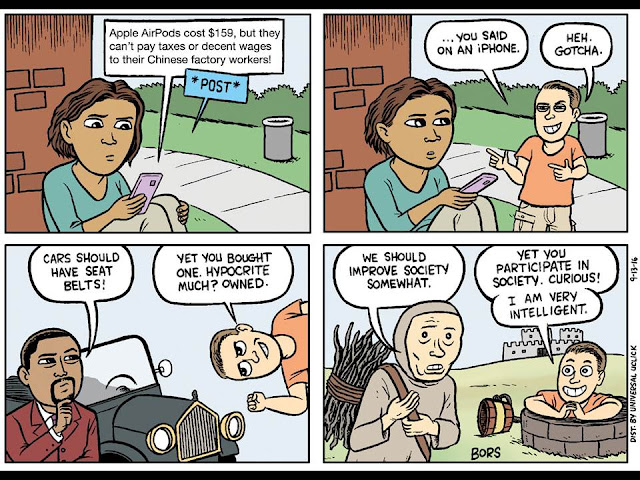

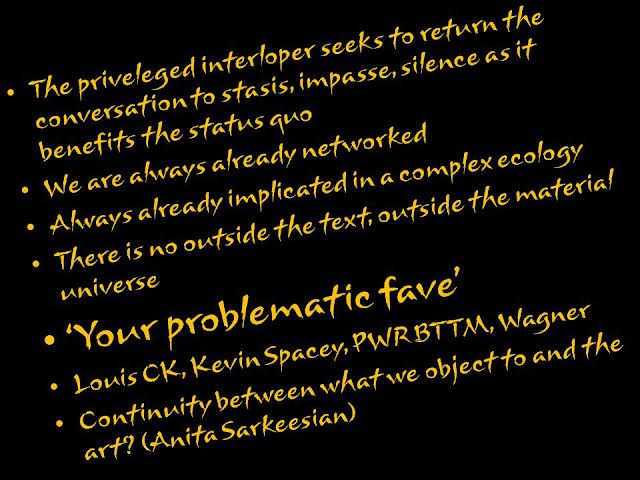

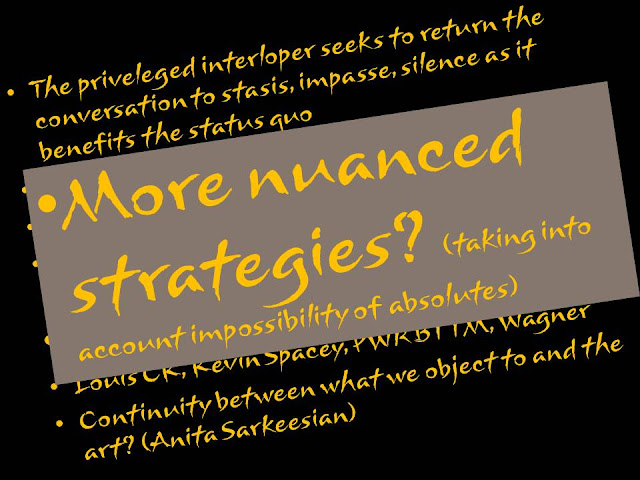

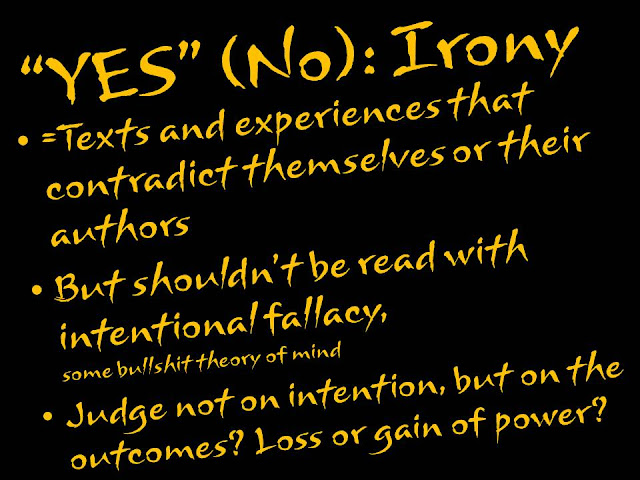

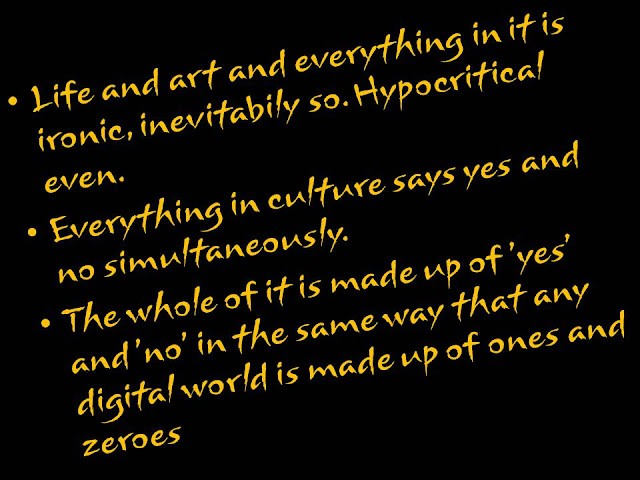

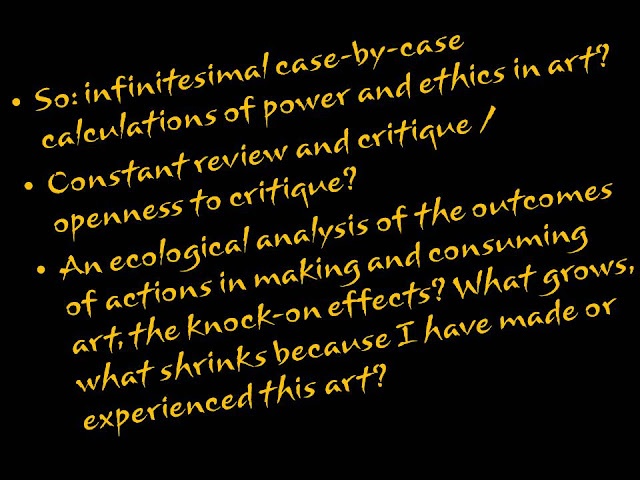

This past weekend I gave a talk about how, why and whether cultural work can refuse the various alienations of modern society / economics, as part of a panel called 'DIY or Die: Is Bartleby Dead in the Post-Digital Age?' at the No! Music Festival at Berlin's Haus der Kulturen der Welt. I don't think the event was recorded, but I thought I'd share my slides / notes on it here, if only because the HKW computer wasn't able to display my outrageous choice of font at the time.

What Sarkeesian says:

What Sarkeesian says:

14-Nov-17

M.E.S.H. - Hesaitix [ 14-Nov-17 6:06pm ]

M.E.S.H. - Hesaitix [ 14-Nov-17 6:06pm ]

M.E.S.H. must be an acronym for something but I haven't bothered finding out what - Making Electronic Shit Happen? - that's probably it. James Whipple does make shit happen - good shit - detailed, interesting electronic shit like Hesaitix. Listening to Mimic just now I kept thinking someone was outside my window, rustling about and banging something so I got up to look and heard that sound again, from the speaker. Whipple's a spook in the speakers, spiriting sounds like...like you can't say what, except for the tolling of bells on Blured Cicada I...and now he's playing ping pong with Robert Henke (you know that sound?), who must be a spiritual brother of sorts, a forebearer, you might say. The difference being the beat, absence of the regular Tech motor Henke uses; instead, more irregular, as on 2 Loop Trip. But whatever messing around there is, he keeps a feeling of movement...the percussion on Search. Reveal is one outstanding aspect of a proper shapeshifting intergalactic gro-o-o-o-ver - yes it is! Whipple maps the space-sound continuum brilliantly, singing the body and brain electric. Damned good.

10-Nov-17

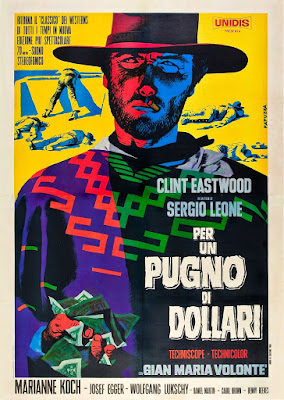

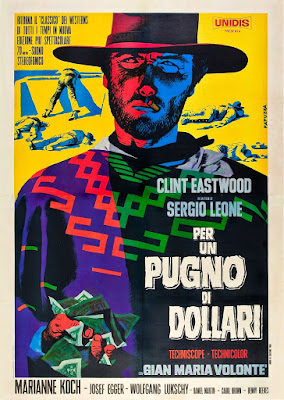

A Fistful Of Dollars [ 10-Nov-17 5:21pm ]

A Fistful Of Dollars [ 10-Nov-17 5:21pm ]

Bought a Clint Eastwood Spag Western box set a few weeks ago but only started watching it recently, beginning, (chrono)logically, with A Fistful Of Dollars. I thought they were due reappraisal, having not watched one all the way through for many years.

One of several things that struck me was the sound, which I only learnt the other day was dubbed on afterwards, thus explaining why every 'clip-clip' of the horses' hooves, jangle of bits and clomp of boots on boards seemed heightened, to the fore. Then the laughter; throughout bad guys spend a lot of time laughing. At times, it's as if some are high on something. The framing of some shots, of course, Leone's recognised for that now, so I wondered why this film, apparently, got such a luke-warm reception from critics. Couldn't they see the artistry involved? Perhaps they were blinded by the amount of gun smoke. If not exactly hailed as a bone fide 'classic' today, this and the subsequent ones are at least rightly hailed as unique.

One other thing that struck me was the similarity between the scene where The Man With No Name is getting his (swollen) eye in again, the shot of his gun hand as he practices to the sound of a militaristic drum beat by Morricone instantly brought to mind Travis Bickle firing to a similar beat by Bernard Herrmann. I may have imagined it, but as you know that military-style drum runs through the Taxi Driver theme.

One astonishing scene is the massacre of the Baxter clan. Leone doesn't depict this in a normal fashion, but hammers home the brutality with almost as many shots of the slayers as bullets they fire. It plays out relentlessly.

By coincidence it's Ennio Morricone's birthday today. The score for A Fistful Of Dollars is great, of course, although as regular readers will know when it comes to playing Morricone scores I favour his Giallo work. Watching the film reminded me of reggae artists' obsession with Spaghetti Westerns, often resulting in hilarious Jamaican/Mexican dialogue. So by way of honouring Morricone, I'm opting for one of those instead of anything by 'Il Maestro'. Featuring adapted dialogue from the film, the now famous coffin joke...

01-Nov-17

Post-Halloween horror treat for you from I Monster: H.P.Lovecreaft read by Dolly Dolly (David Yates) - what's not to like? The musical accompaniment features students at Leeds Beckett University and is pitched just right, avoiding hauntology cliches, opting instead for a blend of dark electronics and even motorik rhythm. Yates' delivery is, as you'd expect, absolutely perfect. Time to throw another log on the fire, light a candle or two and watch the shadows flicker as your skin crawls. Superb. Available as cassette or download here.

03-Aug-17

I'm helping to run and speaking at a study day in London next week, 'Is there a Musical Avant-Garde today?' Come along! We're expecting great research and lively debate, and we're most excited about having a forum for ideas of musical 'avant-gardes' (however you feel about the term) that brings together different musical and scholarly traditions.

I'm helping to run and speaking at a study day in London next week, 'Is there a Musical Avant-Garde today?' Come along! We're expecting great research and lively debate, and we're most excited about having a forum for ideas of musical 'avant-gardes' (however you feel about the term) that brings together different musical and scholarly traditions.

Date: Friday 21st July, 9:45am-5pm.

Location: City, University of London, College Building, Room AG08 (entrance via St John Street, no. 280). Nearest Tube stations: Angel and Farringdon.

Keynote: Jeremy Gilbert (University of East London).

Organising panel: Alexi Vellianitis (University of Oxford), Adam Harper (City, University of London) and Rachel McCarthy (Royal Holloway).

Registration: £8 including lunch and refreshments

If you'd like to attend, click here to register

What would it mean to talk of 'progressive' music today? Applied to the past or, especially, the present, the term 'avant-garde' has largely fallen out of favour within the academy, both as a description of and an imperative for new music. Yet much contemporary music - whichever combinations of limited terms such as 'art', 'popular,' 'classical' or 'commercial' might apply to it - defines itself, if often all too implicitly, in ways most often associated with avant-garde movements: a focus on stylistic complexity and innovation, and an antagonism towards aesthetic norms and the predominant modes of political thought and practice associated with them. But can such a concept still have currency for musicologists and composers?

The aim of this Study Day is to stimulate a broad, interdisciplinary conversation about how, if at all, to talk of an avant-garde in musical cultures today. For the purposes of this conference, the term 'avant-garde' is fluid, but is broadly defined as a particular idea and praxis of a music considered more progressive than certain others.

We invite scholars and practitioners from different fields to address the ways in which musical avant-gardes today are both practiced and discursively constructed. Topics for discussion could include, but are not limited to the following:

Timetable (approximate):

09:45 Arrival and Coffee

10:00 Welcome and Introduction

10:20 Max Erwin: 'Political Music After Sound: Konzeptmusik and the Complicity of the Avant-Garde'

10:50 Alistair Zaldua: '"Small and Ugly": Critical Composition and the Avant-Garde'

11:20 Lauren Redhead: 'The Avant-Garde as Exform'

11:50 (end of first session)

13:00 Rachel McCarthy: '"The Beat Gets Closer': Post-Capitalist Potential in Girls Aloud's 'Biology'

13:30 Adam Harper: 'Object: Resistance: Underground Music Institutions, Discourse, and Representation'

14:00 (ten minute break)

14:10 Alexi Vellianitis: 'Street Culture and the Musical Avant-Garde'

14:40 George Haggett: 'Towards a Sensual Operatic Ekphrasis in George Benjamin and Martin Crimp's Written on Skin'

15:10 (ten minute break)

15:20 Jeremy Gilbert: Keynote

16:05 Plenary Session

17:00 (end)

Abstracts (in chronological order):Max Erwin: 'Political Music After Sound: Konzeptmusik and the Complicity of the Avant-Garde'This paper seeks to clarify the historical, social, and aesthetic precedents, as well as their broader implications, for New Conceptualism in general, with specific reference to the music of Johannes Kreidler, Patrick Frank, and Celeste Oram. Pursuant to this end, I examine Kreidler's work Fremdarbeit (2009) and how it deploys both veiled self-critique and a radical repositioning of artistic engagement, from autonomy to complicity. Such a complicity, I argue, is crucial for understanding the most recent developments in the musical avant-garde, wherein every critique of society/culture/politics is a priori a self-critique; or, as composer Marek Poliks recently put it, "new music 2.0 is new music about new music". I will demonstrate that this self-critical paradigm is nevertheless far from introverted, with an examination of Patrick Frank's discursive-collaborative compositions, especially the "theory-opera" Freiheit - die Eutopische Gesellschaft (2015) which has as its aim no less than the wresting of 1968-style utopia from a material/cynical exhaustion.

In addition, I aim to provide an overview of how a younger generation of New Music practitioners are grappling with the problems exposed by avant-garde culture in general and Konzeptmusik in particular. I examine Celeste Oram's works soft sonic surveillance (2015) and O/I (off/on, 2016) in terms of an attempted reconciliation between the emancipatory potential of technology and its deployment by corporate and government entities.

Keywords: New Conceptualism, Johannes Kreidler, political art, cultural theory

Alistair Zaldua: "Small and Ugly"; Critical Composition and the Avant-Garde

The quotation in the title of this talk is taken from Bruno Liebrucks description of the processes involved in progress: "The next higher step always appears small and ugly in comparison to the lower, and more completed, step."(1) In his article political implications of the material of new music(2), Mathias Spahlinger explains the concept and enactment of 'critical composition'. He seeks to define his choice of musical materials, processes, and open form, as suggestive of a political utopian ideal. Spahlinger locates this historically by describing the importance of atonality: "the appearance of atonality is the very first time in history in which an approach to composition affects all parameters, in particular the fundamental change in the relation between the parts to the whole. From this, all other parameters must follow."(3)

In Spahlinger's conception, atonality is a historical and irreversible moment where historical understanding and progress intertwine. This is a musical movement in which a vision of utopia can be suggested. Spahlinger's approach to composition is self-reflexive and autonomous; Max Paddison describes Spahlinger's aesthetic as one that lays emphasis on the "…largely structural, technical, and methodological aspects of the music itself" rather than one that continues and develops Hans Eisler's engagierte musik, or 'committed' music.(4) The final category Paddison uses to frame his response to Spahlinger's text is of "[…]composition as political praxis in the sense of the now long-standing avant-garde project of the search for the new and not-yet-known through emergent forms." Thus, the criteria of critical composition could be employed in the search for a musical avant-garde.

Open forms and emergent structures are at work in Spahlinger's little known vorschälge(5): a collection of 28 concept, or word scores. These were created for the purpose of both blurring the distinction between composer and performer and 'making the composer redundant'. This talk will examine these pieces through the lens of 'critical composition' and make some tentative suggestions as to how this avant-garde practice could be identified in more recent music.

1. "Die nächst höhere Stufe ist immer klein und häßlich, gegenüber der niedrigeren, in ihrer Vollendung." Liebrucks, B. 'Sprache und Bewusstsein', Trans. Alistair Zaldua

2. Mathias Spahlinger, 'political implications of the material of new music', trans. by Alistair Zaldua, Contemporary Music Review, Vol 34, no.2-3 (2015), 127-166.

3. "Die Atonalität ist die erste Erscheinungsform dessen, was dann alle anderen Parameter ergreift, nämlich eine grundsätzliche Veränderung des Verhältnisses der Teile zum Ganzen in der Musik. Und die anderen Parameter mussten folgen." (Translation: Alistair Zaldua), Spahlinger, M, and Eggebrecht, H. H,'Geschichte der Music als Gegenwart. Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht und Mathias Spahlinger im Gespräch', Musik-Konzepte special edition, edited by Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Reiner Riehn, Munich (2000),16

4. Paddison, M 'Composition as Political Praxis: A Response to Mathias Spahlinger', Contemporary Music Review, Vol 34 (Part 2-3), 2015, 167-175

5. Spahlinger, M. vorschälge: konzepte zur ver(über)flüssigung der funktion des komponisten, Rote Reihe, Universal Edition, UE 20070, (Vienna: 1993)

Lauren Redhead: The Avant-Garde as Exform

Peter Bürger's critique of the historical avant-garde accounts for its ineffectual nature as a movement because '[a]rt as an institution prevents the contents of works that press for radical change in society […] from having any practical effect.'(1) Bürger argues for hermeneutics to be employed as a critique of ideology,(2) as a facet of the understanding of the 'historicity of aesthetic categories'.'(3) The influence of institutions on music 1968 has served as a central part of its critique: the work concept itself seems to enshrine political ineffectiveness and the bourgeois nature of art practice that ought to be critiqued by an avant-garde. Adorno's claim that 'today the only works which really count are no longer works at all'(4) also no longer seems to apply when the relationship of work such as that produced by the so-called Neue-Konzeptualismus(5) with established musical institutions is considered.

In contrast, Bourriaud's concept of the 'exform'(6) re-conceives the avant-garde as outside of institutions and an idea of 'progress' that is aligned with a dominant capitalist ideology. The exformal is 'the site where border negotiations unfold between what is rejected and what is admitted, products and waste', and forms 'an authentically organic link between the aesthetic and the political.'(7) Progress, as part of a capitalist narrative, both creates and abhors waste. Therefore the task of the avant-garde artist is to give energy to this waste, outside of political and ideological institutions. This type of avant-garde practice functions to 'bring precarity to mind: to keep the notion alive that intervention in the world is possible.'(8) This paper explores the exform with respect to the music and art work of the British composer Chris Newman, and considers how Bourriaud's approach to re-thinking the avant-garde might apply specifically to contemporary and experimental music in the

present.

1. Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. by Michael Shaw, Theory and History of Literature, vol. 4 (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, [1984] 2009), p.95.

2. ibid., p.6.

3. ibid., pp15-16.

4. Theodor Adorno, Philosophy of Modern Music, trans. by Anne G Mitchell and Wesley V Blomster (New York: Continuum, 1973), p.30.

5. cf. Johannes Kreidler, 'Das Neue am Neuen Konzeptualismus', published as 'Das Neue and der Konzeptmusik', Neue Zeitschrift für Muzik, vol. 175, no. 1 (2014), pp44-49, de/theorie/Kreidler__Das_Neue_am_Neuen_Konzeptualismus.pdf> [accessed 13.05.2017].

6. Nicholas Bourriaud, The Exform, trans. by Erik Butler, Verso Futures (London: Verso, 2016).

7. ibid., p.10.

8. ibid., p.47.

Rachel McCarthy: 'The Beat Gets Closer': Post-Capitalist Potential in Girls Aloud's "Biology"'

A recent body of Leftist socio-political theory advocates a transformational approach to post-capitalism. Inspired by Brecht's maxim 'don't start from the good old things but the bad new ones', as well as Lenin's suggestion that capitalist institutions such as banks could be re-purposed for socialist ends, writers including Jameson (2010), Williams and Srnicek (2014), and Mason (2015) posit that a future beyond capitalism must be secured not through a rupture with present society, but rather by a transformation of already-existing phenomena. Jameson identifies utopian potential in the organisational structures of Wal-Mart, while Williams and Srnicek promote accelerationism as a means of pushing through the bonds of capitalism.I suggest that the music of the mainstream pop group Girls Aloud represents an aesthetic parallel to this kind of political theory. With roots in the reality television talent show Popstars, capitalist relations of production are deeply embedded in the group's music. Yet analysis of their 2005 hit single 'Biology' demonstrates how, in deviating from the structural norms of mainstream pop, the song contains a striking kernel of utopian impulse. This is further complicated by the disturbing sense of jouissance that pervades the song's reception, whereby a 'critical' enjoyment of mainstream pop can amount to having one's cake and eating it too. Ultimately, 'Biology', like Jameson's assessment of Walmart, should be understood dialectically: neither as a regressive symbol of the evils of capitalism nor as a shining beacon of hope for a post-capitalist future, but as something in between.Adam Harper: 'Object: Resistance': Underground Music Institutions, Discourse and RepresentationHow might a sonic avant-garde go hand in hand with a progressive social ideology today? Might an enlarged set of sonic possibilities correspond to greater social representation? Taking the term 'representation' in both its political and aesthetic senses (that is, the representation of emotion, experience and so on), this paper hopes to begin to approach these questions in the light of a number of recently established collectives and institutions within underground music that explicitly provide platforms specifically for women (such as Sister, Discwoman and Objects Limited), people of certain regional or diaspora contexts (such as NON and Eternal Dragonz), or people of certain sexualities (such as KUNQ). What sort of discourse surrounds such collectives? What are their goals and are they achieving them? To what extent do they combine the musical and the social in redistributing representation?Alexi Vellianitis: 'Street Culture and the Musical Avant-Garde'This paper looks at ways in which certain metaphors or rhetorical strands linked to the musical avant-garde have been mobilised to describe interactions between new classical music and 'urban' music (grime and electronic dance musics) on the London classical concert scene since 2000. In particular, it is concerned with a fetishisation of the 'the symbolic power of street culture[, which] is often understood as authentic, defiant and vital' (Ilan, 2015). Seen as such, this symbolic power shares much with the classical avant-garde, since modernist or avant-garde status has historically been conferred on the basis that music signals 'political engagement and commitment', and is linked to and fuels 'periods of political instability, change, revolt, and revolution' (van den Berg, 2009).In order to unpack these issues, this paper focuses a number musical performances around London over the past decade: two BBC Proms concerts, in which grime was featured alongside the BBC Symphony Orchestra; and the musical activities of composer and producer Gabriel Prokofiev, whose nightclub and record label Nonclassical brings classical music to clubs throughout London, and whose orchestral music brings 'urban sounds into the concert hall' (Shave, 2011). In each case, accusations that the classical concert scene is being 'dumbed down' by featuring popular music are countered by arguments that this 'urban' popular music is in some way new, current, or vital.These concerts foreground questions about race, class, and inclusivity that have been dominant in public discourse. Is this a positive diversification of classical music culture, or just another set of appropriations of black, working-class music by white, affluent musicians? What is it about the experience of social unrest in urban areas that speaks to the political pretentions of the avant-garde? What change, if any, is being effected?George Haggett: Towards a Sensual Operatic Ekphrasis in George Benjamin and Martin Crimp's Written on SkinThere is little in Katie Mitchell's production of George Benjamin and Martin Crimp's 2012 opera Written on Skin that goes unseen: not only does the thirteenth-century plot feature an on-stage orgasm, but throat-slitting, evisceration, cannibalism, and suicide. Nevertheless, when these lurid events are painted by 'the Boy' (the heroine, Agnès's, illicit lover), the audience can never see them. Instead, during what Crimp and Benjamin term 'Miniatures', he takes out a page and, singing, describes the illumination that he has painted onto it. In so doing, he turns his pictures into uttered acts of ekphrasis, the rhetorical device through which visual art is described in detail.In asking how operatic ekphrasis can function and unpacking its potency in Written on Skin, I will do three things: 1) lift ekphrasis from its specificity to the reified, written word and into the performative realm of the sung act; 2) refer outwards from Written on Skin's Troubadour source text to locate its viscera within thirteenth-century understandings of the body; 3) analyse each miniature in turn to interrogate Benjamin's compositional responses to these conditions. Integrating the former two, I will dissect Written on Skin into four sensory organs—eyes, ears, skin, and mouths—and lodge them between Miniature analyses. My intention is to bring the body to the fore, always in pursuit of a reading that hears the body when it hears ekphrasis, and hears ekphrasis when it hears the body.

06-Jul-17

Garrett David [ 06-Jul-17 3:54pm ]

Garrett David [ 06-Jul-17 3:54pm ]

Ross From Friends [ 05-Jul-17 1:11pm ]

Ross From Friends [ 05-Jul-17 1:11pm ]

Chaos In The CBD [ 05-Jul-17 1:08pm ]

Chaos In The CBD [ 05-Jul-17 1:08pm ]

Blondes [ 03-Jul-17 10:04am ]

Blondes [ 03-Jul-17 10:04am ]

Playlist - June [ 03-Jul-17 9:56am ]

Playlist - June [ 03-Jul-17 9:56am ]

Grant [ 01-Jul-17 11:08am ]

Grant [ 01-Jul-17 11:08am ]

Grant totally blew me away with his album cranks and the even earlier one the acrobat as well. Two heavyweight deep house albums. So glad to see he is back on lobster t. for a new release. Cannot wait for this one.

09-May-17

Playlist - April [ 01-May-17 10:01am ]

Playlist - April [ 01-May-17 10:01am ]

Octo Octa [ 29-Apr-17 6:08pm ]

Octo Octa [ 29-Apr-17 6:08pm ]

Mood J [ 27-Apr-17 5:06pm ]

Mood J [ 27-Apr-17 5:06pm ]

Baltra [ 27-Apr-17 5:00pm ]

Baltra [ 27-Apr-17 5:00pm ]

Beacon [ 27-Apr-17 6:54am ]

Beacon [ 27-Apr-17 6:54am ]

No Moon [ 26-Apr-17 2:24pm ]

No Moon [ 26-Apr-17 2:24pm ]

Keysound Rinse FM March 2017 show ft Ganesa [ 01-Apr-17 12:48pm ]

Keysound Rinse FM March 2017 show ft Ganesa [ 01-Apr-17 12:48pm ]

Negativity, Not Pessimism! (RIP Mark Fisher) [ 15-Jan-17 6:59pm ]

Negativity, Not Pessimism! (RIP Mark Fisher) [ 15-Jan-17 6:59pm ]

(7D7B46C409699693BB5299F3ECF1319C).jpg) I was so shocked and upset to learn of Mark Fisher's death yesterday. For me, Mark was both an idol and, as time passed, someone I was always pleased and not a little humbled to encounter in person and sometimes share a platform with. I didn't know Mark very well personally, and being a generation younger than he was I only know second hand the milieu of the 90s and the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at Warwick University he formed an integral part of, through its growing legacy and some of the reminiscences and thoughts of people who knew him then (Robin MacKay, Simon Reynolds and Jeremy Greenspan among them). But as someone a generation younger than Mark, I can express something about the incalculable impact he had on me, my thinking and writing, and my gratitude for the times when he actively, kindly helped me, as well as the times that were just good times.

I was so shocked and upset to learn of Mark Fisher's death yesterday. For me, Mark was both an idol and, as time passed, someone I was always pleased and not a little humbled to encounter in person and sometimes share a platform with. I didn't know Mark very well personally, and being a generation younger than he was I only know second hand the milieu of the 90s and the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at Warwick University he formed an integral part of, through its growing legacy and some of the reminiscences and thoughts of people who knew him then (Robin MacKay, Simon Reynolds and Jeremy Greenspan among them). But as someone a generation younger than Mark, I can express something about the incalculable impact he had on me, my thinking and writing, and my gratitude for the times when he actively, kindly helped me, as well as the times that were just good times.

Mark simply changed my life. By 2009, the year I started the blogging, he was a central node in a network of bloggers, thinkers and forums that encompassed critical theory, philosophy and several areas of cultural criticism, especially of popular music. It was a conversation and a community I eagerly wanted to participate in, late and all too hot-headed though I was. As commissioning editor of Zer0 books, he fostered the growth and evolution of this network into a collective of thinkers built on diverse, self-contained and regularly powerful statements that went far.

Mark's own essay for the imprint, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? was undoubtedly one of the best of the lot. I continue to recommend it widely as one of the best, most distilled expression of today's ideological challenges. By the end of 2009, Mark had reached out to me and asked if I wanted to write for Zer0. I was 22. Infinite Music was the result two years later. He told me that I should reconsider the title I had initially proposed - 'The New New Music' (can you believe that!?) - which didn't take Mark's genius, but thank God. His faith in me - this despite my frequent and often crude HTML critiques of his positions on music - led to so many amazing opportunities and blessings for the struggling, wet-behind-the-ears critic I was.I first met Mark in person in April 2010 when we were both part of a panel discussion at London's Café OTO, a 'salon' under the auspices of Wire magazine: 'Revenant Forms: The Meaning of Hauntology'. He was warm, friendly and funny back stage, powerful, precise, provocative and funny on-stage. Someone I brought to the event who didn't know Mark and his ideas said to me 'but capitalism is the only system that works!' (this of course is precisely was Capitalist Realism describes and addresses). I believe I next saw him marching alongside thousands of students at one of the protests against the raising of tuition fees and the cutting of the university teaching budget in late 2010, an issue that inflamed and unified the blog network like nothing else, not least Mark himself.At some point in 2011 I was at a gig behind a pub at which Maria Minerva was playing. Maria had been taught by Mark during her Master's at Goldsmith's college. In an amazing moment, Maria gave a shout-out on stage to her 'professors' - I followed the direction of her outstretched arm, and there was Mark, leaning against a wall next to Kodwo Eshun. I saw him at least twice in 2013, once at a symposium at Warwick University on the Politics of Contemporary music, where I burned with envious ambition at his ability to deliver such an on-point, appropriate and funny lecture from only a small notebook. The other time was in Berlin, where I was talking about accelerationist pop for the CTM festival, Mark was there to talk about the death of rave. We walked from our hotel to the venue, had lunch, and Mark talked sympathetically and encouragingly about my career difficulties. He sat in the front row of the talk I gave. I played some of the kitschiest vaporwave as the audience came in. I'll never forget the bemused look on his face, as if he was trying to figure out what sort of a hilarious prank was being played, and whether he wanted in on it. That image of Mark is still for me the opposite end on the spectrum of vaporwave listeners to the one where vaporwave is, uncritically, 'just good sincere nostalgic vibes', and why I have no regrets about 'politicising' vaporwave (a genre that in any case owes an enormous debt to his theorising of hauntology).But for me there was another Mark as well - the formidable writer and theorist, k-punk. This voice I began to get to know in 2006, the year when he did so much to lay the foundations of hauntology (it was his invention, frankly). It was from k-punk that I learned about something called 'neoliberalism' ('what on earth has this guy got against liberalism?' I would wonder). It was from k-punk that I learned that post-modernism was not necessarily the wonderful cultural emancipation I had naively believed it to be. In fact, during these years I was mostly against k-punk. He was critical of more recent trends in electronic music, believing them a poor comparison to what the 90s had offered. This led to a fierce division between writers and bloggers that manifested not just in blogs but magazine sites and a day-long conference at the University of East London, which I attended (the first time I saw Mark in the flesh). Though we both agreed that new music was necessary, naturally his position irritated my young, idealistic self with my special music, and my own blog posts attempted to intervene in support of the new stuff. 'Loving Wonky', my first blog post to attract more than a handful of readers, was directed at k-punk implicitly throughout and at its conclusion, explicitly.This negativity that got me started, this need to talk back to the authority figure, was a testament to the power of his writing. But more so was the way he subsequently taught me as I took a closer look. In preparation for my post on hauntology, I printed out and re-read everything he'd written on or near the subject, underlining and making notes. And he convinced me of his position. He was right. I didn't want to accept his theorising of 'the end of history', thinking it merely pessimistic. His blog posts are so imaginatively, seductively, persuasively written. He's probably the most referenced person on Rouge's Foam. Then I read Capitalist Realism, and rather than the mere youthful defence of certain musics it could have been, Infinite Music became an attempt to stand with Capitalist Realism and answer k-punk's resounding call for a newfound creative imagination. Later, in 2012, it was from k-punk that I learned of accelerationism, and because of his theory that I used it to describe new forms of electronic music in 'Welcome to the Virtual Plaza.' And it wasn't only theory. Wherever I wrote about music and Mark was writing too (Wire, Electronic Beats), my writing was improved by the honour and by his raising of the bar (this was the guy who had described Michael Jackson as 'only a biotic component going mad in the middle of a vast multimedia megamachine that bore his name.')Mark isn't just the figure behind every significant thing I've done as a critic. His theory is now deeply embedded in who I am and what I say. Even the residue of the ideas I have fought against condition my thinking. I have brought his concepts home, they structure my conversations with my friends and family. Capitalist realism: describing the ideology that miserable as it is, there is no alternative to capitalism and that's just the way it is. Business ontology: the ideology that any social or cultural structure must exist as a business. His use of the concept of the Big Other - the imaginary subjectivity that holds important beliefs but may not in fact exist - has guided me through my personal response to Brexit and Trump. (By the way, I couldn't possibly summarise Mark's writing - if you haven't read it already, what are you waiting for?) Even his blackly comic image of a broken neoliberalism, as a cyclist dead and slumped over the handlebars yet continuing downhill and gathering speed, keeps coming back to me.Mark eventually became something of a role model to me. Asked what sort of space I wanted to carve out between academia and public criticism for my own career, I have often said I wanted to be a Mark Fisher. Yet as he regularly explained with his astonishing balance of passion and precision, the world as it is today, its ideologies and its institutions - it's hardly set up to encourage fringe intellectuals. I'm not sure whether he would have fully encouraged me to aspire to his career, tied so closely as he well knew to challenges of mental health (something I started to live in 2014 when, initially and like so many others, my PhD went nowhere). But he did warmly support and encourage my writing when so many people around me could only regard it with doubt.One of Mark's most abiding lessons, and for me at least the key to his writing, was something he put pithily to me at the end of an email: 'Negativity, not pessimism!' I had not appreciated the subtle but important difference the two, but then I instantly did. What a rallying call for the nightmarish 2010s. And as others have noted, it was his encouragement and optimism that was especially nourishing. It was certainly not a pessimistic new-music naysayer who wrote the final words of Capitalist Realism:

20-Dec-16

Keysound Rinse FM Christmas Special December 2016 [ 20-Dec-16 4:46pm ]

Keysound Rinse FM Christmas Special December 2016 [ 20-Dec-16 4:46pm ]

Keysound show Rinse FM November 2016 [ 01-Dec-16 11:17pm ]

Keysound show Rinse FM November 2016 [ 01-Dec-16 11:17pm ]

I think it really gripped me when it went black.

Then just legs and...

I like this. Feels like a tape some kids find and decide to play in the old VCR in the cabin that they've rented for the weekend.

I don't know anything else about this band / person but I'm gonna start digging now...

21-Oct-16

Rinse FM Keysound show tracklists Summer - Autumn 2016 [ 21-Oct-16 5:05pm ]

Rinse FM Keysound show tracklists Summer - Autumn 2016 [ 21-Oct-16 5:05pm ]

Valerie [ 09-Sep-16 1:33pm ]

Valerie [ 09-Sep-16 1:33pm ]

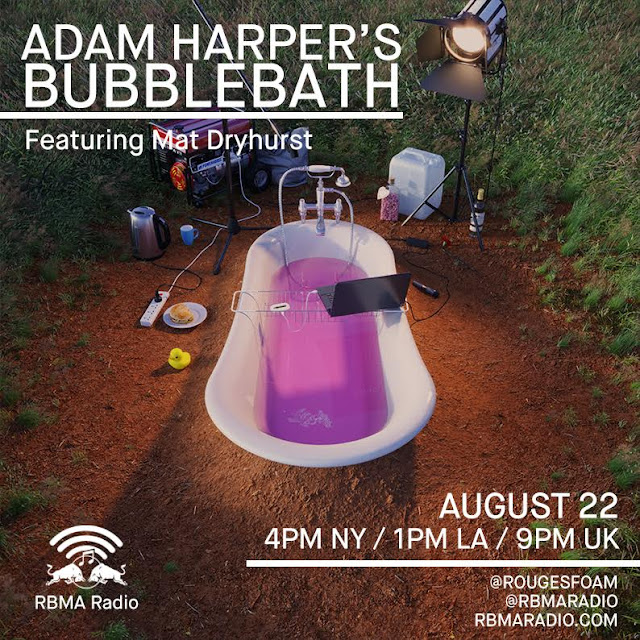

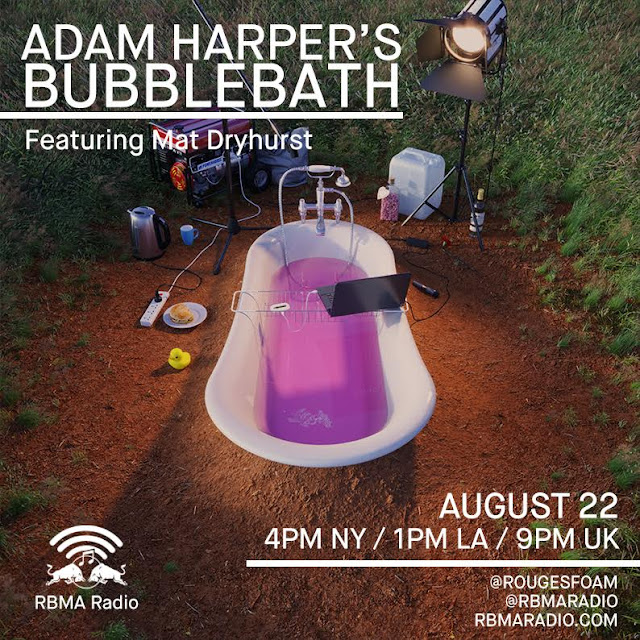

Bubblebath Episode 01 ft. Mat Dryhurst (for RBMA Radio) [ 25-Aug-16 5:04pm ]

Bubblebath Episode 01 ft. Mat Dryhurst (for RBMA Radio) [ 25-Aug-16 5:04pm ]

Art by Kim LaughtonThe first episode of my new monthly show for RBMA Radio aired a few days ago, and is archived here. Bubblebath is a two-hour show all recorded and edited by me, featuring new, typically lesser known tunes that I'm interested in, segments going for some deeper analysis, and interviews with various people from underground music culture. For the first show, I looked at the pseudo-humanistic style of James Ferraro's Human Story 3 and some other records, and talked to Mat Dryhurst about some of the problems facing underground culture today and his platform Saga. The playlist is below.

Art by Kim LaughtonThe first episode of my new monthly show for RBMA Radio aired a few days ago, and is archived here. Bubblebath is a two-hour show all recorded and edited by me, featuring new, typically lesser known tunes that I'm interested in, segments going for some deeper analysis, and interviews with various people from underground music culture. For the first show, I looked at the pseudo-humanistic style of James Ferraro's Human Story 3 and some other records, and talked to Mat Dryhurst about some of the problems facing underground culture today and his platform Saga. The playlist is below.

People in the US won't be able to listen to the archived version of the show for various legal reasons. I didn't realise that would happen and I do apologise. If that's you, you might try using a proxy server, especially with different browsers. US listeners can listen to the show live without any problems, though, so I'll make sure to forewarn people next time.

· 00:00:02 - 00:02:41 Julien - Alpha Beat - Calm (from Calm 2 https://calmdot.bandcamp.com/album/calm-2)

· 00:02:41 - 00:05:28 Alfie Casanova - 4 Play - Calm (from Calm 2 https://calmdot.bandcamp.com/album/calm-2)

· 00:05:28 - 00:10:16 NKC - Salon Room - Her Records (from Hague Basement http://store.herrecords.com/album/hague-basement)

· 00:10:16 - 00:13:03 仮想夢プラザ - 秘密 - Plus 100 Records (from Balance with Useless https://plus100.bandcamp.com/album/balance-2) (extract, background, and again throughout )

· 00:13:03 - 00:18:17 Julien - Day Racer - Orange Milk (from FACE OF GOD https://orangemilkrecords.bandcamp.com/album/face-of-god)

· 00:18:17 - 00:23:52 NV - Bells Burp - Orange Milk (from Binasu https://orangemilkrecords.bandcamp.com/album/binasu)

· 00:24:50 - 00:29:57 Easter - Leda - own Bandcamp page (from New Cuisine Part 2 https://easterjesus.bandcamp.com/track/leda)

· 00:29:57 James Ferraro - various tracks from Human Story 3 - own Bandcamp page (https://jjamesferraro.bandcamp.com/album/human-story-3) (extract, background)

· 00:32:04 - 00:37:32 James Ferraro - Individualism - own Bandcamp page (from Human Story 3 https://jjamesferraro.bandcamp.com/album/human-story-3)

· 00:39:19 - 00:40:31 John Adams - Lollapalooza - Nonesuch (from I Am Love Soundtrack) (extracts)

· 00:40:55 - 00:41:20 Steve Reich - Eight Lines Number 1 - RCA Red Seal (extract)

· 00:41:36 - 00:42:30 Aaron Copland - Allegro from Appalachian Spring - Sony Classical (from Bernstein Century: Copland) (extract)

· 00:43:05 - 00:44:32 Jeffery L. Briggs - CivNet Opening Theme - Microprose (from CivNet Soundtrack) (extract)

· 00:44:48 - 00:45:24 Oneohtrix Point Never - Problem Areas - Warp (from R Plus Seven) (extract)

· 00:45:52 - 00:46:11 Kara-Lis Coverdale - AD_RENALINE - Sacred Phrases (from Aftertouches https://sacredphrases.bandcamp.com/album/aftertouches) (extract)

· 00:46:30 - 00:47:04 Giant Claw - DARK WEB 005 - Orange Milk (from DARK WEB https://orangemilkrecords.bandcamp.com/album/dark-web) (extract)

· 00:47:25 - 00:47:51 Metallic Ghosts - University Village - Fortune 500 (from City of Ableton https://fortune500.bandcamp.com/album/the-city-of-ableton) (extract)

· 00:48:58 - 00:49:59 Torn Hawk - The Romantic - Mexican Summer (from Union and Return) (extract)

· 00:52:12 - 00:55:08 Subaeris - Shadow Portal - Nirvana Port (from Transcendent God https://nirvanaport.bandcamp.com/album/transcendent-god)

· 00:55:08 - 00:58:23 Subaeris - Beating Heart - Nirvana Port (from Transcendent God https://nirvanaport.bandcamp.com/album/transcendent-god)

· 00:59:08 - 01:01:16 Klein - Babyfather Chill - own Bandcamp page (from ONLY https://klein1997.bandcamp.com/album/only)

· 01:01:16 - 01:03:45 Klein - Make it Rain - own Bandcamp page (from BAIT https://klein1997.bandcamp.com/album/bait)

· 01:04:49 - 01:47:38 Valentin Silvestrov - Diptych - ECM (from Valentin Silvestrov: Sacred Works) various tracks from Valentin Silvestrov: Silent Songs - ECM (extracts, background)

· 01:49:09 - 01:54:25 Swimful - Atop - SVBKVLT (from PM2.5 https://svbkvlt.bandcamp.com/album/pm25)

· 01:54:25 - 01:58:45 Swimful - Bounce (Simpig Remix) - SVBKBLT (from PM2.5 Remixes https://svbkvlt.bandcamp.com/album/pm25-remixes)

24-Aug-16

'Joy 2016' (essay for 3hd festival, where I'll be in October) [ 24-Aug-16 5:12pm ]

'Joy 2016' (essay for 3hd festival, where I'll be in October) [ 24-Aug-16 5:12pm ]

Art by Sam Lubicz3hd festival is back for its second year in Berlin this October, and its website has gone up (click here). I'll be there lecturing and participating in discussions over various aspects of their theme 'There is nothing left but the future.' In the meantime, I wrote an essay for them (click here to read it) sketching some initial thoughts about some of the problems facing musical futurism and musical sarcasm after a summer of violence and Brexit, through the lens of the 'Ode to Joy' from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, and Wendy Carlos's electronic version of it particularly (incidentally, Jeremy Corbyn, something of a lightning rod for various kinds of political tumult whatever you think of him, recently mentioned listening to Beethoven's 5th).

Art by Sam Lubicz3hd festival is back for its second year in Berlin this October, and its website has gone up (click here). I'll be there lecturing and participating in discussions over various aspects of their theme 'There is nothing left but the future.' In the meantime, I wrote an essay for them (click here to read it) sketching some initial thoughts about some of the problems facing musical futurism and musical sarcasm after a summer of violence and Brexit, through the lens of the 'Ode to Joy' from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, and Wendy Carlos's electronic version of it particularly (incidentally, Jeremy Corbyn, something of a lightning rod for various kinds of political tumult whatever you think of him, recently mentioned listening to Beethoven's 5th).

Beethoven's Ode to Joy has accumulated cultural and political baggage of apparently every different kind, and, especially, in extremes. It has played the role of humanity's highest and most noble achievement and an incitement to horrifying violence both. And it is the anthem of the European Union...

Who needs dehumanising machine music when you have Trump, when you have the rise of hatred the world over?

There is an important difference, of course, between the future and the futuristic. The futuristic is a costume, a thrill, a performance, a caricature, all from within the safety of the present. The future is what actually happens to you and at some point, whoever you are, it will hurt you. What can art and music help us to do and to say before that point?

Include Me Out [ 20-Feb-18 4:11pm ]

Where The Action Is... [ 20-Feb-18 4:11pm ]

10-Jan-18

Various - (not) open to question [ 10-Jan-18 5:55pm ]

Whilst the New Year may be open to question the quality of the work on this album is not. Furthermore, you're invited by the label to make your own additions to these tracks, the first layer 'is created within the collaboration of MƩCHΔNICΔL ΔPƩ and Les Horribles Travailleurs', so the challenge is set, although this is very much in the spirit of collaboration rather than competition. As always, the bar is set high here but why not (re) create? Remake/remodel (should be a Roxy Music title...oh, it is?). 'You are invited to finish this soundwork by altering\adding layers etc. to the first layer, which can be downloaded from Bandcamp'. As it stands it's very good.

New Year: So What [ 09-Jan-18 4:47pm ]

Let's start the New Year with a whimper...@',mn,mn,qwwwwwhhhhhhhhherrrr'

Fact is this year's going to be the one that sees the downfall of the music industry due to it's incessant gnawing of itself like a doped-up rabid labradoodle, foaming as it very slowly chews its own leg off and keeps going as far as it can reach until it's stinking innards spool out across everything but don't worry, you will be immune to the putrid, poisonous substance due to years of injecting the antidote in the form of JS Bach, James Brown, Bernard Parmegiani and other names involving capital 'B', or 'L', or 'D'...how about 'D'? Don Cherry, Defunkt...that's enough, that's the ABC of it, your alphabetically registered pantheon of ....music people...the countermeasure to all the crap...

On the subject of letters...

That one's called AB...there's more of my art over here

Whatever...or, actually, all my art work this year will be part of a series called So What...why? I reckon it's the most common response.

In 2018, though, let's not be blase about things, least of all what we love the most and what we make...

Blackdown [ 1-Jan-18 11:36pm ]