This album from last year, but only recently made available digitally. I picked Glow World up on vinyl originally and have been spinning it consistently since. A masterclass in detailed world-building, it has to be one of my prized vinyl purchases of late. Everyone knows Rod Modell, but I am sure some people may not have realized that Taka Noda, also released under a dub moniker, Mystica Tribe on Silent Season for a few years. The two make a perfect duo on this timeless record.

And just as you think we'd exhausted the Modell treasure trove in the past few months, he just released another LP of sublime icey textures on 'Northern Michigan Snowstorms'. The sub-zero chillout room from one of Michigan's most renowned immersive techno producers.

Single Cell Orchestra - Single Cell OrchestraOur upcoming release from Monoparts couldn't be further from the sound on this album, but in a twisted rabbit hole way, posting about Olga's upcoming album on Instagram led me to this overlooked classic when asking for people's favorite trip-hop tracks. I love it when older 90s albums crop up on the corners of Bandcamp. For a new platform, I am always dubious of finding gems when hitting the search bar. Silent Cell Orchestra is the perfect capsulation of the freedom of sound and styles found across albums in an era when feelings beat genres.

ESP Institute XV - I Active, II Passive, III Unobtanium [L.A. WILDFIRE FUNDRAISER]There have been a few amazing LA fire fundraiser comps released in the past month or so, and I am sure many of you managed to wrap your ears around the 'For LA' comps, which are a no-brainer of epic proportions within the ambient producer realm.

This one from ESP Institute, however, took me by surprise. I mean, where do you even start? 90 tracks from a label that is consistently pushing genre boundaries and coming up with some defining albums (those early Lord of The Isles, as just one example). I debated doing an entire collected post with 5 of my favorite tracks at one point.

After giving this a spin in its entirety as I hopped around the house and car, it's the type of album you could listen to all day long and always find new moments. The sequencing is subtle but definitely considered. You find your ears pricking up to a beautiful new sound every two tracks or so. My choice track is by the vinyl digger officianado, Chee Shimizu, presenting a truly uplifting Balearic sunset vibe on Zeze... save this one for the summer.

OK, just two more choice cuts then…

Band Ane - Anish MusixMost of you know I love the playful IDM vibes of artists such as LJ Kruzer, Freescha and ISAN. It's been a while since any of those have produced any new music of note, and it's rare to stumble across something that evokes similar feelings nowadays. I don't know why though. Twenty years later, is it all just too serious now? Has the innocence in electronic music just disappeared? Is it not cool to create playful melodies anymore?

I can't remember how this album by Danish artist Band Ane, ended up on my wishlist to purchase, it might have been playing on the Deep Space radio station. An innocent album of whimsical, melodic IDM that takes you back to the early 00's.

Voice Actor, Squu - Lust (1)Listening to Voice Actor's debut on Stroom felt like a voyeuristic snapshot of personal photographs. Abstract, minimal, field recordings, vocal shards- you never knew the twist it was going to take from track to track. Now the enigmatic Stroom label return with Voice Actor alongside 'Squu', (who I know very little about -perhaps on purpose, as the only profile I can find is this Soundcloud).

Squu brings a dubby and trippy metallic sheen to Voice Actor's fragmented musings, turning the abstract, into an almost danceable, yet much more listenable epilogue.

Find these albums and many more over on my Bandcamp Collection.

Volume 7 is an ASIP artist-related special; on the odd chance you missed some of the amazing records put out by our small extended world of producers. I was thinking of maybe starting a new rating system for ASIP alumni - something along the lines of "How Annoyed I Am ASIP Didn't Release This Out Of Five."

Alex Albrecht - Someday SaraAlex Albrecht on Anjunadeep wasn't on my 2025 bingo card, but listening now, it makes complete sense. Alex's sensibility and stewardship of —quite simply— feel-good music can be heard through his ambient field recordings all the way to the warm-up dance floor. Anjuna veers towards the more accessible side of things, of course, so here Alex has dialed up the beats, but kept consistent with the organic instruments and storied pianolines.

If you liked his release here on ASIP, imagine this record as Disc Two (Evening) versus our Disc One (Daytime) to put it in 90's Trance Compilation verbiage.

Abul Mogard & Rafael Anton Irisarri - Live at Le Guess Who?Guido and Rafael's 2024 collaboration, Impossibly Distant, Impossiblt Close, is the most fitting album title I've ever encountered. Listening to it on headphones was a revelation—an immense soundscape unfolding while the smallest details surfaced with startling clarity. Naturally, experiencing this record of the duo playing live is just as mesmerizing.

Also, Berliners, please note our very own Lihla will be performing at the same show as these two greats on March 20th… don't miss!

Yagya - VorShawn Reynaldo (First Floor) recently featured this album in his newsletter, and his short review pretty much hit the nail on the head. Something along the lines of- and I may be paraphrasing here with my own POV- 'dub techno is getting pretty popular again, but no-one does it better than some of the overlooked OGs'. Well, Yagya is one of the OGs, and on Vor, he returns to his purest manifestation. Bellowing clouds of dubby warmth take you right back to the tin shed pitter-patter vibe of Rigning, with more confident flourishes to be found after years of perfecting his style.

Deepchild - BelovedRick Bull swings from banging techno to swirling moods of ambiance over on his Bandcamp, so it's hard to know when to dive in if you only enjoy one of the two (luckily, I enjoy both!) 'Beloved' is a similar vibe to his vocal approaches on his ASIP release 'Mycological Patterns', and in a textured Burial-esque way, can be even more engrossing and intriguing at points.

Markus Guentner - Black DahliaMarkus has been getting some amazing and well-deserved praise for his new album on Affin, Black Dahlia. You don't need to ask me, his #1 fan if it's any good… But those who listen to Markus' music are a special breed in today's overbearing world. His music and sound design are truly enveloping, and great rewards can be found if attention is given from front to back. Black Dahlia is a precious reminder of this attentive listening approach, as Markus has taken an even more metallic and experimental approach to his usual widescreen world-building - it's not all comfort in there, but the reward is just the same.

Jo Johnson - Alterations 1: UnbrokenJo is up there with some of the masters of synthesizer minimalism, but instead of pioneering the sound in the 70's, she's keeping the atmospheric and dystopian side of this music well and truly alive. And I mean that in a positive light, of course. Much darkness can be found in her compositions, but she is never overbearing to the point of negativity. It was her delicate approach alongside Hilary Robinson that made their 9128 release so glorious, and once again, this record is another class in session.

No embed enabled on this one, so head on over and dive in.

Find these albums and many more over on my Bandcamp Collection.

You could say ASIP has brought me closer to 'my people' over the years—those with a deep, almost obsessive appreciation for all things ambient and electronic. The ones who love this music, who show up at the same gigs, who get so inspired by the sounds and stories that they start paving their own.

Based in Rotterdam, Rosillon is one of those people. Co-founder of the electronic music platform Embodiment, he's been a long-time listener and supporter of ASIP. At his core, he's just another music obsessive, choosing to share his passion through mixes and curated events—the kind of person who keeps music culture moving forward, regardless of genre or scale. Last November Rosillon had the pleasure to play for the first edition of ZERØBPM, a 18 hour non-stop ambient/meditation experience in a church in the Netherlands. And his previous mixes have cropped up for the brilliant Deep Breakfast series, as well as the Korean collective, Vurt.

I don't typically accept submissions for the isolatedmix series, but his vinyl-only mix landed in a way that many don't. And when he shared the story behind it, it perfectly captured how music like this isn't just heard—it's experienced, absorbed, and ultimately, passed on. Listening back and reading his inspiration, it reminded me of the exact mindset I experienced when picking a name for this endeavor, A Strangely Isolated Place.

Places of inspiration for Rosillon's mix

~

" Last summer, during my travels through Bulgaria, I found myself deeply inspired by the landscapes, and the sense of remoteness that each place evoked. As soon as I returned home, I aimed to translate these experiences into sound.

This mix is the result of that, a sonic exploration of isolation, both physical and emotional. The concept behind this set revolves around the idea of 'isolated places', not just in the geographical sense, but also within the mind. These are the places that trigger emotions, memories, and introspection. Places shaped by sound aesthetics that speak directly to the imagination. With this in mind, I carefully selected tracks that embody these feelings, crafting a mix that serves as both an escape and a reflection.

The mix unfolds as a metaphor for the experiences we gather during our journeys. It begins at an airport, a symbolic starting point that sends the listener on their way. From there, the music takes you through a collage of progressively more obscure destinations, each transition serving as a portal to another isolated place.

Places of inspiration for Rosillon's mix

Some transitions are smooth and fluid, while others are abrupt and disorienting, mirroring the unpredictability of travel itself. As the mix progresses, it immerses the listener in various emotional landscapes, reflecting the highs and lows that come with discovering unfamiliar territory.

Near the end, a vocal announcement signals that the gate is closing, marking the inevitable conclusion of the journey. The bittersweet nostalgia of leaving behind an enriching experience is captured in a track featuring glitching sounds layered over a field recording of an airport.

astrangelyisolatedplace · isolatedmix 129 - RosillonHowever, just as in real life, the end of a trip brings with it a renewed appreciation for the lessons learned and the memories made. In the closing section of the mix I wanted to embrace this sentiment, offering a positive and empowering conclusion.

It reminds us that every journey, whether to distant lands or within ourselves, leaves a lasting impact, shaping our perspective in ways we may not fully grasp until we return home. I hope this mix transports you to your own isolated places, allowing you to lose yourself in the journey and find meaning in the sounds along the way."

- Rosillon

Listen on Soundcloud the ASIP Podcast or the 9128.live iOS and Android app

Tracklist (vinyl only)

01. The Black Dog - M1 [Dust Science Recordings]

02. Rod Modell - Ghost Lights B-side [Astral Industries]

03. Inhmost - In The Bay [re:st]

04. 3.11 - Dissolve in Patience [PRS]

05. Box5ive - Rough Sleeper [co:clear]

06. 3.11 - Hard Copy [PRS]

07. Alva Noto - Confidential Information 1 [Noton]

08. Off The Sky - Ahurani [re:discovery records]

09. Xenia Reaper - 23724 [INDEX:Records]

10. William Selman - Farther Off Among The Foaming Black Rocks [Mysteries Of The Deep]

11. Pontiac Streator & Mister Water Wet - Angelus Spit [Motion Ward]

12. TIBSLC - Hypertranslucent [Sferic]

13. Quiet Places - Side B [A Strangely Isolated Place]

14. The Black Dog - Lounge [Dust Science Recordings]

15. Alva Noto - HYbr:ID Ectopia Field 1 [Noton]

~

Rosillon Soundcloud | Instagram

Embodiment Soundcloud | Instagram

Words + Photos ANDREW PARKS

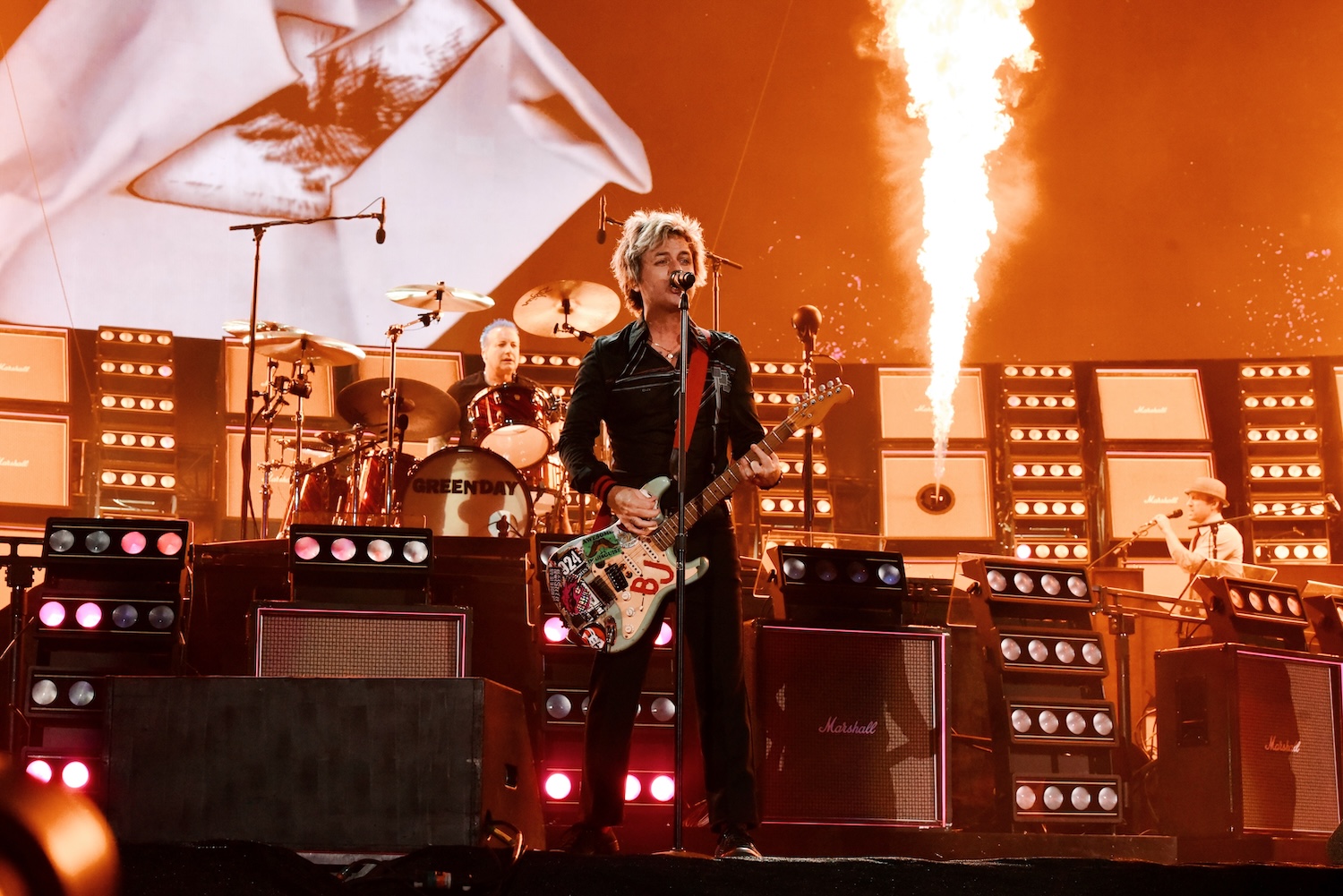

If there was ever any doubt as to the staying power of Green Day, it was obliterated before the punk band even hit the stage at Target Field in downtown Minneapolis on Saturday night. Aside from the obvious — a stadium that felt much fuller than it had for a fierce Smashing Pumpkins set — there was no denying the sudden energy spike as Queen and The Ramones had their biggest hits (“Bohemian Rhapsody” and “Blitzkrieg Bop”) blasted the way they would be at a proper baseball game.

By splitting the difference between pogo-oriented punk and operatic rock, Green Day wasn’t just ensuring a grand entrance. They also seemed to be tipping their dye jobs toward the two divergent forces (grand ambition and true grit) that informed their biggest albums: 1994’s diamond-tipped Dookie and 2004’s Broadway-bound American Idiot LP.

You read those years right; much like Woodstock’s mud-caked pivot towards the mainstream (arguably Green Day’s breakthrough moment), Dookie recently turned 30. And American Idiot, well, it’s old enough to drink in every country but ours. They’ve both aged as well as the band, too — as likely to drive nearly 40,000 people wild as they’ve ever been.

Maybe even more so considering their original fanbase is in full-on nostalgia mode, and the group can now afford to punctuate their many overlapping hooks and melodies with dynamic light displays, towering backdrops, and fire-spewing speaker cabinets. All while barely taking a breather despite having played both albums in full, along with a handful of other hits (“Know Your Enemy,” “Brain Stew,” the song that said goodbye to Seinfeld).

As for where American Idiot‘s political bent falls in a far more contentious year than the one that gave George W Bush another go, frontman Billie Joe Armstrong had this to say: “We need unity! And this is fucking unity tonight!”

Then, after quickly squashing any Democrat vs. Republican discussions, he added, “This isn’t even a party tonight…. It’s a celebration! I want you to scream out for joy; are you ready?”

They were all night, to be honest. Thanks to absurdly tight performances by The Linda Lindas, Rancid, and the Pumpkins — a band long criticized for bloat, cramming 13 crackly originals and one cacophonous U2 cover into a one hell of a power hour — a concert that started at the ungodly hour of 5:30 and ended close to 11 never felt that way.

More like a reminder of what made the MTV era and shows like 120 Minutes so vital in the days before digital music. Or as Rancid guitarist/vocalist Lars Frederiksen said before launching into a lovely rendition of “Ruby Soho,” “Thanks for the last 33 years…. If there’s none of you, there’s no us.”

There are a few LPs I have been hunting down for a long time now, and the original Dreamfish 2LP is up there. I've never seen it in the wild, and a Bandcamp comment suggests only 500 copies were originally pressed back in 1993. Silent State is slowly working through some of the most majestic titles from this era, and now Dreamfish is up for reissue, with preorders on Feb 7th. Read this interview I did with Nils from Silent State a while back who is on a mission to share more from the Namlook estate.

Snad - BubblescopeI've been on a Smallville kick recently - well, probably since the Joe Davies album reminded me they exist, and they constantly churn out some of the best house music going. This latest one from Snad was playing in Passenger Seat Records in Portland when I asked what it was… of course, it turned out to be on Smallville. A lovely slice of dubby relaxing house music to float away to. The B-side, the standout.

Kiln - Seltzer BoaEvery year since 2021, Kiln has offered up a single through Bandcamp on January 1st, as a sonic snapshot of their groovable electronics. Many will know of this group through their releases on Ghostly, defining a specific sound that is perhaps the most organic and instrumental way possible to approach the listenable side of early IDM. Look out for more from Kiln arriving very soon….cough cough.

PFM - Equilibrium VIPIt's not often you get an unreleased gem from one of the kings of atmospheric / liquid drum'n bass making an appearance on Bandcamp. PFM has been dropping a bunch of singles on his own bandcamp in recent years (often deleting the releases once people have downloaded them), but looks like this one is set to stay, with a vinyl press to boot.

Roller.

Simon Littauer - ModularEveryone hates on Instagram for many reasons, but once in a while, if you follow bunch of music nerds, it presents you with… more music nerds, jamming in front of their expensive rigs. Most sound as you'd expect, but Simon Littauer's got a knack for intertwining some absolutely beautiful pads and melancholy amongst the complex analog glitch and breaks. This album is name your price right now, too.

Find these albums and many more over on my Bandcamp Collection.

Well, if the last few weeks in LA have not been traumatizing enough - and then we've had the hideousness of the inauguration and unfolding horror of the first few days of Trump: The Return... on top of all that, there's also been a flurry of sad-making deaths.

Saddest for me was learning that the writer Geoff Nicholson had gone. I didn't know Geoff well - but he was a fellow Brit expat in Los Angeles and on the occasions we ran into each other socially, I really enjoyed talking with him. I have been meaning to pick up his tomes on walking and on suburbia - and now have the spur.

The book of Geoff's I have read and returned to repeatedly over the years is Big Noises. One of his earliest books - his first non-fiction effort - and I believe the only one he wrote about music.

Here's something short I wrote about Big Noises for a side-bar to an interview I'd done for some magazine or other (can't remember which, can't recall when). They asked me to enthuse about three music books I loved but which were a bit forgotten. Below that blurb is a longer piece in which Geoff and Big Noises pops up in the context of guitar solo excess.

BIG NOISES by GEOFF NICHOLSON

Big Noises (1991) is a really enjoyable book about guitarists by the novelist Geoff Nicholson. It consists of 36 short "appreciations" of axemen (and they're all men; indeed, it's quite a male book but quite unembarrassed about that). These range from obvious greats/grates like Clapton/Beck/Page/Knopfler to quirkier choices like Adrian Belew, Henry Kaiser, and Derek Bailey. Nicholson writes in a breezy, deceptively down-to-earth style that nonetheless packs in a goodly number of penetrating insights. I just dug this out of my storage unit in London a couple of months ago and have been really enjoying dipping into it.

Flash of the Axe: Guitar Solos

from Excess All Areas issue on musical maximalism, The Wire, September 2019.

I can distinctly remember the first time I let myself enjoy a guitar solo. 1983, I'm at a party, "Purple Haze" comes on - I just went with Jimi, surrendered to the voluptuous excess. There was a sense of crossing a boundary within myself, like sexual experimentation, or trying a food that normally disgusts you.

You see, growing up in the postpunk era, we were all indoctrinated with less-is-more. Exhibitions of virtuosity were frowned upon. Folklore told us of a time before punk, a wasteland of 12-minute drum solos and other feats of "technoflash" applauded by arenas full of peons grateful to be in the presence of their idols. Minimalism wasn't just an aesthetic preference but a moral and ideological stance: an egalitarian levelling of rock's playing field, letting in amateurs with something urgent to say but barely any chops. Gang of Four went so far as to have anti-solos, gaps where the lead break would have been. Postpunk was an era of amazingly inventive guitarwork, but even the most striking players, like Keith Levene, were not guitar-heroes in the "Clapton Is God" sense. The guitar was conceived as primarily a rhythmic or textural instrument. An example of how the taboo worked for punk-reared ears: David Byrne's unhinged guitar on "Drugs" sounded fabulous, but Adrian Belew's extended screech on "The Great Curve" made me flinch.

There was a sexual politics aspect to postpunk's solo aversion: the guitar, handled incautiously, could be a phallic symbol. Willy-waving nonsense was resurging with the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Bands like Iron Maiden were competing for the hearts and minds of youth. So if you supported the DIY feminist-rock revolution represented by the likes of Delta 5 (tough-girls and non-thrusting males united), you made a stand against masturbatory displays of mastery. Solos were, if not outright fascist, then certainly reactionary throwbacks to guitar-as-weapon machismo.

In those days, on the rare occasions I liked anything Old Wave - Blue Oyster Cult's "(Don't Fear) The Reaper," say - the solo would be something to grimly wait through until the good stuff resumed (the Byrdsy verses). Then came Jimi, triggering a rethink. Another key moment in punk deconditioning came ironically courtesy of one of the class of 1977: Television, who I also heard for the first time in 1983. Where Hendrix's "Purple Haze" solo lasts just 20 seconds, Tom Verlaine's in "Marquee Moon" is a four-minute-long countdown to ecstasy. Its arc is unmistakably a spiritualized version of arousal and ejaculation, building and building, climbing and climbing until the shattering climax: an extraordinary passage of silvery tingles and flutters, the space of orgasm itself painted in sound.

The mid-Eighties was coincidentally when the idea of the guitar-hero began to be tentatively rehabilitated within post-postpunk culture, from the Edge's self-effacing majesty to underground figures like Meat Puppets's Curt Kirkwood, who channeled the spectacular vistas and blinding light of the desert into his playing. Then came Dinosaur Jr.'s J. Mascis and his phalanx of foot-pedals, churning up - on songs like "Don't"- not just an awesome racket, but solos that were sustained emotional and melodic explorations. In interviews, Mascis namedropped long-forgotten axe icons like James Gurley of Big Brother and the Holding Company. Paul Leary and his band Buttholes Surfers signposted their influences more blatantly: even if Hairway to Steven's opener hadn't been titled "Jimi", its blazing blimps of guitar-noise would've reminded you of "Third Stone From the Sun".

This kind of winking, irony-clad return to pre-punk grandiosity was the rage in underground rock as the Eighties turned to Nineties. But where Pussy Galore covered (with noise-graffiti) the entirety of Exile on Main Street, that band's Neil Hagerty, in new venture Royal Trux, stepped beyond parody towards something more reverent and revenant. The pantheon of guitar gods - Neil Young, Keith Richards, Hendrix - inhabited ghost-towns-of-sound like "Turn of the Century" and "The United States Vs. One 1974 Cadillac El Dorado Sedan". But the effect was more like time travel than channeling - the abolition of a rock present that Trux found unheroic.

As a young critic during this period, I tried to stage my own abolition, a transvaluation that erased the now stale and hampering postpunk values I'd grown up with and ushered in a new vocabulary of praise: a maximalist lexicon of overload and obesity. Revisionist expeditions through the past were part of this campaign. When Lynyrd Skynyrd's "Freebird" had been inexplicably reissued as a single in 1982 and became a UK hit, I could not have imagined anything more abject. But reviewing a Lynyrd box in 1993, I thrilled to the swashbuckling derring-do of that song's endless solo, a Dixie "Marquee Moon" whose slow-fade chased glory to the horizon.

This was the final stage of depunking: the enjoyment of lead guitar as pure flash. At a certain point in rock history, solos ceased to have an expressive function and became a self-sustaining fixture, existing only because expected. Soon I found myself taking pleasure in such excrescences of empty swagger as John Turnbull's solo in Ian Dury's "Reasons To Be Cheerful." I even started looking forward to Buck Dharma's spotlight turn in "(Don't Fear) The Reaper".

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Apart from a few academic studies of heavy metal, a surprising dearth of serious critical attention has been paid to the guitar solo. The exception that springs to my mind is the novelist's Geoff Nicholson's Big Noises, a collection of pithy appreciations of thirty-six notable guitarists, ranging from obvious eminences like Jimmy Page to cult figures like Allan Holdsworth and Henry Kaiser. But although Nicholson is insightful and evocative when it comes to a particular player's style or sound, and generally revels in loudness and in-yer-face guitar-heroics, he rarely dissects specific solos. Perhaps it is simply very hard to do without recourse to technical terms. At the same time, the mechanics of "how" do not actually convey the crucial "what"—the exhilarating sensations stirred in the unschooled listener.

Why does the discrete spectacular display of instrumental prowess get such short shrift from rock critics? Partly it's because of the profession's bias towards the idea of communication—seeing music as primarily about the transmission of an emotion, a narrative, a message or statement. Prolonged detours into consideration of sheer musicality is seen as a digression, or even as decadent. I think another factor behind this disinterest in or distrust of the guitar solo is a lingering current of anti-theatricality - the belief that rock is not a form of showbiz, that it has higher purposes than razzle-dazzle or acrobatics. A guitar solo is like a soliloquy, but one that is all sound and fury, signifying nothing (or nothing articulable, anyway). It's also similar to an aria, that single-voice showcase in opera, the most theatrical of music forms. Adding to the distaste is the way that guitar soloing is typically accompanied by ritualized forms of acting-out: stage moves, axe-thrusting stances, "guitar-face." This makes the whole business seem histrionic and hammy, an insincere pantomime of intensity that's rehearsed down to every last grimacing inflection rather than spontaneously felt; an exteriorized code rather than an innermost eruption.

How would you start to formulate a critical lexicon to defend, or at least, understand, this neglected aspect of rock? In the past, I've ransacked Bataille's concept of "expenditure-without-return", seeing a potlatch spirit of extravagance at work in the sheer gratuitousness of sound-in-itself. That in turn might connect the soloist's showing-off to an abjection at the heart of performance itself - the strangeness of exposing one's emotions and sexuality in front of strangers. Another resource might be queer theory and camp studies, especially where they converge with music itself, as in Wayne Koestenbaum's book about opera, The Queen's Throat. The guitar hero could be seen, subversively, as a diva, a maestro of melodramatics.

The ultimate convergence of these ideas would be Queen - the royal marriage of Freddie Mercury's prima donna preening and Brian May's pageant of layered and lacquered guitars. Queen's baroque 'n' roll made my flesh crawl as a good post-punker, but as a no-longer solo-phobe, I've succumbed to their vulgar exquisiteness. From the phased filigree of "Killer Queen" to the kitsch military strut of "We Will Rock You", May's playing is splendour for splendour's sake - a peasant's, or dictator's, idea of beauty. Anti-punk to the core, and perhaps the true and final relapse of rebel rock into show business.

THE CURE

Pulse, June 1992

by Simon Reynolds

Robert Smith sits alone at the office of Fiction, the U.K. label of the Cure, the band he formed at age 17 and has led for a decade and a half since. It's a rare opportunity to meet one-on-one with the group's vocalist, songwriter and sometimes-guitarist; determined to promote the idea that "The Cure Is A Band," all of Smith 's recent encounters have seen him flanked by his cohorts: drummer Boris Williams , guitarists Porl Thompson and Perry Bamonte , and longest serving Cure member, bassist Simon Gallup

Tonight the ageless Smith , who's wearing eyeliner but no trace of lipstick, looks somewhat drained after a five hour session with his accountant, doubtless administering the lucre generated by the Stateside success of the Disintegration album and the "best of" compilation Standing on a Beach/Staring at the Sea. After years as a cult icon, the Cure is now a big band, but without the coarsening and adherence to formula that such mass popularity usually requires.

The Cure began in 1976 as the Easy Cure, then a trio, spurred into being by punk's do it yourself fervor. The groups 1979 debut, Three Imaginary Boys, lay somewhere between power pop and the edgy, art-punk-minimalism of Wire and Siouxsie and the Banshees, the latter of whom Chris Parry signed to Polydor before starting his Fiction label, with the Cure as its flagship. (With a few early singles tagged on, the debut is titled Boys Don't Cry in the US, where the groups albums are available on Elektra/Fiction, unless otherwise noted.) With Seventeen Seconds (1980) and Faith (1981), the Cure's tormented angst-rock garnered an intensely devout cult following. By Pornography (1982), the group's music had reached a peak of morbid introspection that many found impenetrable. After this high-point of alienation Smith veered toward pop with the vaguely dance-oriented Lets Go To Bed and The Walk singles. But it was only with 1983's Lovecats that the Cure really got a handle on the joie de vivre of pure pop. A singles collection, Japanese Whispers (Fiction/Sire in the US), marked the breakthrough.

Thereafter, the Cure's albums - The Top (1984), The Head on the Door (1985) and Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987) - explored both life's dark side and its light-hearted aspects; stylistically, the group shed the oppressively homogenous sound of its angst era for a kaleidoscope of psychedelic, art-rock and mutant pop textures. Disintegration(1989) was a slight return to the morose Cure of the early 80's, but that didn't prevent the first single Love Song, from reaching number two on the US charts. By the end of the decade the Cure had sold over eight million records worldwide without ever having settled into a predictable career trajectory or losing its innate combustibility. As Smith once put it, If I didn't feel the Cure could fall apart any minute, it would be completely worthless.

Despite Smith and his group's contrary nature, much of the new album Wish , is surprisingly in sync with the British alternative state-of-art - not that Robert Smith 's ever been afraid to be affected by the pop climate (remember the New Order tribute/pastiche of Inbetween Days from Head On The Door ?). But on Wish it sounds like he's been listening closely to the British movement of "shoegazers" or "The Scene That Celebrates Itself", and in particular to Ride and My Bloody Valentine (both bands for which he professed admiration). You can hear it in the super saturated Husker Du meets Hendrix maelstrom of End, in the oceanic iridescence of From The Edge Of The Deep Green Sea, and in the gilded, glazed guitar mosaics of High and To Wish Impossible Things, all of which vaguely resemble shoegazers like Slowdive and Lush. The Cure has made these kinds of noises before (indeed, a number of shoegazers have been influenced by Smith 's group and Siouxsie and The Banshees). But it hasn't made them for a while, and never in such a timely fashion.

"I definitely think it would have been a totally different record if we'd had the same songs but recorded them at the time of Disintegration," Robert Smith agrees. But he says it was actually recording the wah-wah tempest of Never Enough (the only new song on the group's 1990 remix album, Mixed Up) that made the Cure want to be a guitar band again.

According to Smith , when keyboard player Roger O'Donnell slipped out of the group after the Disintegration tour, the Cure decided to replace him with another guitarist, Perry Bamonte . "Porl Thompson 's always been very guitar oriented, he's got loads of old guitars and amps and he's always very worried about his sound. In the past he's probably been restrained by the group and by the way I've always liked things to be very minimal. But this times everyone's played out a bit more. Because we didn't have a keyboard player, no one was really bothered with working out keyboard parts. On Disintegration there were all these lush synthesizer arrangements, but this time we tried to do it mostly with guitars. We also had in mind the way it feels live, to play as a guitar band; its so much more exciting."

The new album is a stylistic mixed bag, whereas Disintegration was a more uniform, emotionally and musically: a steady wash of somber sound and mood. Wish spans a spectrum of feelings from giddy euphoria to deep melancholy, from bewilderment to idyllic nonchalance.

"Disintegration was less obviously varied as this album," says Smith , "but there were songs like Lullaby, Love Song, Fascination Street, that were nothing to do with the rest of the album. But overall there was a mood slightly...downered. Even on Lullaby there was a somber side to it. Whereas on this album there are some out-and-out jump in the air type songs."

Some of Wish's songs are fairly legible, like the poignant Apart, which deals with the desolation that comes when a gulf inexplicably opens up between lovers. Others are harder to fathom. "End beseeches, "please stop loving me, I am none of these things, but it's not clear if the plea's addressed to the Cure fans, Smith 's wife, to a friend...

"It's kind of a mixture", says Smith . "In one sense, its me addressing myself. It's about the persona I sometimes fall into. On another level, it's addressed to people who expect me to know things and have answers - fans, and on a personal level, certain individuals. And it has a broader idea, to do with the way you fall into a way of acting that isn't really true, but because it's the easy path, it just becomes habitual even though it's not really the way you want to be. Sometimes whole relationships are based on these habits. It goes beyond my circumstances as a star, because I think a lot of people put on an act. I think I had it at the back of my mind when I wrote the song that when it came to performing it live, it would remind me that I'm not reducible to what I am doing. I do need reminding, because it's got to the scale where I could quite happily fall into the rock star trip. It might seem like its quite late in the day for it to all go to my head, since we've been going so long, but the success has reached the magnitude where it's insistent and insidious.

On End, Smith also bemoans the fact that all my wishes have come true. It must be something that he's felt at several points in his career: been there, done that... so what now? .

"Any desires I have left unfulfilled," says Smith, "are so extreme that there's no chance of them ever happening. I would really love to go into space, I always have since I was little, but as I get older, it's less and less likely that I'd pass the medical! The only things that I wish for are the unattainable things. Apart from that, I don't really have strong desires, except on behalf of other people. Generally, peace and plenty. My wishes are more on a global level. To Wish Impossible Things Is specifically about relationships. The notion of Three Wishes, all though history, has this aspect where if you wish for selfish things, it backfires on the third wish. But wishes never seem to take in the notion of wishing for other people, general wishes, or wishes about interacting with other people. In all relationships, there's always aching holes, and that's where the impossible wishes come into it"

"Doing the Unstuck: seems to be about disconnecting from the hectic schedules from productive life, and drifting in innocent blissful indolence. It's something Smith wishes he could do more often.

"I was going to say that my biggest wish was not to have to get up in the morning, and that's not strictly true, but there are days when I feel like that. It's like watching models saying that they've got a glamorous life, and then you find out that they can't eat what they want, they can't drink, they have to get up at five in the morning and get to bed by nine at night, and the truth is that they don't do anything glamorous at all except walk up and down the catwalk and wander about in front of cameras. It's one of those myths that modeling is glamorous, because it looks like glamour. And sometimes I think to myself ,'I'm free, I don't have to get up', but that's not the case cos I'm always doing something. Sometimes there are days where I refuse to do my duties. And I think there should be moments in everyone's lives where they take that risk and say 'Oh fuck it, I'm not prepared to carry on functioning'. I suppose that's a feeling you would associate with being in the Cure. Unstuck is about throwing your hands in the air and saying, 'I'm off'. But then again there is a thread running through the Cure that's all about escapism."

In fact, a lot of what the Cure is about is a refusal, or at least a reluctance, to grow up, to desire to avoid all the things (responsibility, compromise, sobriety) that come with adulthood. Despite being a very big business, at the heart of the Cure is a spirit of play.

"I met some people recently," says Smith, "and I guessed really wildly and inaccurately about their age. I thought they were in their forties, but they were only two years older than me, in their mid-30's. They'd passed across the great divide. Some of it's to do with having children. I don't see why they can't continue being like a kid. Obviously you change as you grow old, you become more cynical, but there are people that manage to avoid that. I know a couple people that are still quite a bit older than me, but are still genuinely excited by things; they do things and really get caught up in them. Children can do that, get caught up in non-productive activity, but its harder and harder to do that as you get older. At least, not unless you take mind- altering substances, of course!"

Robert Smith grew up in Crawley, a quintessentially English suburb. And the Cure's following has always consisted of that handful of lost dreamers in every suburban small town, that together make up a vast legion of the unaffiliated and disillusioned, who dream of a vague "something more" from life but secretly deep down inside know they will probably never get it. The Cure has always had an escapist, magical mystery side to their music, but the other half of its repertoire has been mope rock, forlorn and mournful for the lost innocence of childhood, and the prematurely foregone possibilities of adolescence.

Smith himself, however, is not so sure that the Cure represents lost dreams for lost dreamers; he's reluctant to reduce Cure fans to a type.

"I think our audience has now got so diverse where it seems weird to talk in general terms about what we represent to them. The Cure is liked by some people that I don't even like! There's people who like us just because we do good pop singles like High. There's other people who'd die for the group. When it gets to that level, people who are really caught up in the band,it's frightening to be a part of it, because I know that we don't understand anything better than those people. We represent different things to different things to different people, even from country to country. Even to different sexes and to different age groups. Polygram commissioned a survey of Cure fans, because I've had this long running argument with record companies about what constitutes our audience. The companies believe the media representations of the Cure audience as all dressed in black, sitting alone in their bedrooms, being miserable. And they were shocked at the actual breadth of the Cure audience. I don't know what we represent to them. I don't even know what the Cure represents to me! If we hadn't had the good songs throughout our history, to back up our attitude, we wouldn't have gotten this far. All that stuff about what we mean to our fans is too muddled to unravel really. We are a very selfish group. We don't worry about what we represent."

But perhaps its this very self-indulgence that is part of the Cure's appeal. Most people are obliged to forego following their whims and fancies, are forced to be responsible and regular. Perhaps the Cure represents a life based on exploring your own thoughts, exploring sounds, being playful. Smith thinks this might be true of its hardcore audience, the people who like us past a certain age. But at heart, he's wary of dissecting the what is exactly it is that the Cure's following get out of the group, or why they're so devoutly loyal.

"Maybe too much emphasis is placed on our hardcore fans. I feel sometimes like I'm crusading on behalf of something, and that this is going to pin me down to something that I'd ultimately resent. I've been through that with Faith and Pornography, people wanting me and the Cure to stand for something." Smith 's referring to his early-80's status as Messiah for the overcoat-clad tribe of gloom and doomers. "All that nearly drove me round the bend and I don't need any encouragement."

Part of Robert Smith 's appeal, at least to the female half of the Cure following, has always been his little lost boy aura. Bright girls dream of a boy who does cry, who's vulnerable, sensitive, even though few find one. Even now he still seems more like a "boy" than a "man". (Smith has just turned 33, Wish was released on his birthday, April 21)

"I was faced by this dilemma with the lyrics of Wendy Time on the album. It's the first time I've used the word 'man' in relationship to myself in a song. So it is seeping through into music. Five years ago, the line in question would have been 'the last boy on earth.' I've always been worried about doing music past the age of 30, about how to retain a certain dignity. The vulnerable, lost little boy side of my image is gradually disappearing, if it isn't gone already. But the emotional side of the group will never disappear, I'm in the unusual position of having four very close male friends around me in this group; I don't feel the slightest bit of inhibition around them. I've got more intimate as I've got older."

Around the time of Disintegration, Robert Smith declared," I think we're still a punk band. It's an attitude more than anything".

The history of the last 15 years of British rock has been a series of disagreements about what exactly that attitude was. Groups have gone on wildly different trajectories - from ABC to the Style Council to the Pogues to the KLF- in pursuit of their cherished version of what punk was all about.

"Living in Crawley, travelling up to London to see punk gigs in 1977", reminisces Smith, "what inspired me was the notion that you could do it yourself. The bands were so awful I really didn't think, 'if they're doin it, I can do it'. It was loud and fast and noisy, and I was at the right age for that. Because of not living in London or other big punk centers, it wasn't a stylistic thing for me. If you walked around Crawley with safety pins, you'd get beaten up. The risked involved didn't seem to make sense. So luckily there aren't any photos of me in bondage trousers. I thought punk was more a mental state.

"The very first time we played at our school hall, we bluffed our way in by saying we were gonna play jazz-fusion, then started playing loud fast music. And that made us a punk band, so everyone hated us and walked out, but we didn't care cuz we were doin what we wanted. I suppose that all punk means to me is: not compromising and not doing things that you don't want to do. And anyone who follows that is a punk, I guess. But then, that could make Phil Collins punk, if he's genuinely into what he does!"

The Cure was never a threat; its particular effect was more on the level of mischief or mystery. Groups who start out making grand confrontational gestures tend to buckle rather quickly and turn into transvestites. But the Cure has endured by being elusive, indeterminate, unpredictable. It's sold a lot of records but it has never pandered.

"We've never really been bothered with confronting people. We've gradually become more accepted, just 'cos we've been around for so long. We've upset a lot of people in the business 'cos we've shown that you can do things exactly how you want and be successful. Most confrontational gestures are so shallow that they're laughable. The KLF carrying machine guns at the British record industry awards - you just have to look at the front page of any newspaper to put that kind of gesture in proper perspective. There should be confrontation in pop, but I think the people doing it often believe they are achieving a lot more than they actually are. The premeditated, Malcolm McLaren idea of confrontation is lamentable. Things are only really threatening if someone does something for it's own sake and it happens to upset people. The only time we've come close to that is the Killing an Arab debacle."

That song was grossly misconstrued as racist by sections of the US media. In fact, it was inspired by Camus' novel The Stranger, the story of a nihilistic young man in French colonial Algeria, who, involved in an altercation with a native, chooses to pull the trigger out of sheer fatalistic indifference. Embroiled in unwanted controversy, Smith was obliged to defend himself, denouncing his accusers as Philistine bigots. "For a couple of days we made the national news in America. And it was the last thing in the world I wanted to get caught up in. Debating Camus on US cable television was totally surreal."

The Cure hasn't been subversive so much as topsy-turvy: by cultivating its capacity for caprice and perversity, it's managed to remain indefinable.

"It's very difficult, having been around so long; a persona builds up around you that's continually reinforced despite your attempts to break away from it. It's like trying to fight your way out of papier-mache; There's always people sticking bits of wet newspaper to you all the time. I conjure up in my mind figures like Jim Kerr [of Simple Minds] or Bono, and I always have an image of what they represent. It might be really far away from the truth, but they're trapped in it. I often hear people say or read things about me and the group and they are completely at odds with how I think about us. We do things from time to time that are mischievous, and in the videos we play around with caricatures of ourselves. But at other times, we're not really mischievous: That implies that we're doing things for nuisance value, and we never have. We can't win really: we're either considered a really doomy group that inspires suicides or a we're a bunch of whimsical wackos. We've never really been championed or considered hip, and so we've never been treated as a group that stands for something, like, say Neil Young or the Fall have. Which I'm glad about, but the downside is that we're dismissed as either suicidal or whimsical."

For all Smith 's belief that the "attitude" has been a constant, the Cure didn't really draw much from the punk, apart from the initial impetus to do-it-themselves. Punk's main influence on the Cure was minimalism, a distaste for sonic excess. Hence, the clipped crisp power pop of Boys Don't Cry, the terse, translucent, bleakly oblique Seventeen Seconds. When the Cure tried to develop musically, while still inhibited by punks less-is-more aesthetic, the result was the grey draze of Faith and the angst - ridden entropy of Pornography - some of the most dispirited and dehydrated music ever put to vinyl. But once the Cure stepped out of the fog of post-punk production and into the glossy light of Love Cats, it wasn't long before the group became what it always essentially was, an art-rock group, maximalist rather than minimalist, indulgent rather than austere. And then came the over-ripe, highly strung textures of The Top and Head on the Door, the sprawling art-pop explorations of Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, the lush luxurious desolation of Disintegration.

The truth is that punk rock was just a blip, a brief interruption, in the perennial tradition of English art-rock. Robert Smith was once described by the Aquarian Weekly as "the male Kate Bush", which is probably going way too far, but it does highlight the way the Cure enjoys the English art- rock blessing/curses of eccentricity, self-consciousness, stylization, preciousness. Above all, the Cure has always been a literate band. Smith is a voracious reader. Recent input includes Stendhal ("very trying"), Blaise Cendrars ("very peculiar"), the poems of Catullus ("very ribald"). And Nietszche.

"I just read Ecce Homo, which he wrote at the end of his life, when he was going mad. It's Nietszche summing up his life and his work, and it's pretty disturbing, by the end he's majestically deluded. I also read a book about Nietszche and that era. I didn't realize that his sister founded New Germania in Paraguay. She took 82 perfect Aryan specimens and attempted to found the new super race. The colony is now virtually extinct, because there was so much inter-breeding over four generations.

"I try and combat this feeling that I'm missing out on something very fundamental to life that I should have by now realized, by reading ferociously. And I still come to books that have been recommended to me by people I consider wise, and I always wonder "have I missed the point, or is this something I knew anyway". I think it's really worrying, getting older and not really knowing anything more intellectually. I don't think I know any more than when I was 15, except on an experiential level. I only know things that I wish I didn't know. But I never really craved wisdom. I enjoy the discussions we have in the group. Everyone's well read. The discussions can soar sometimes".

Which leads on to another set of polarities that Robert Smith oscillates between. On one hand, he's arty and literate; on the other, he's very much 'an ordinary bloke', partial to beer, soccer, Indian food, soap operas.

"I don't think its two sides to my character; its all me. In the group we have quite intense emotional conversations about things. At the same time, we can go to the pub and get so drunk that I don't remember how I got home, but I don't feel bad about it later; I don't think it doesn't fit with how I'm supposed to be. Equally, I wouldn't feel embarrassed if someone asked me what I was reading at the studio, and I said Love by Stendhal. I never feel guilty about either end of the spectrum. I object to people who only exist to go down to the pub, or people who think 'oh no, you can't watch football, its just a pack of men kicking a ball 'round a field.' I would feel weird excluding one aspect 'cos I felt it wasn't appropriate. It's all me."

recycled as

The Cure: Robert Smith's Wish List

Christmas 1992 issue of Melody Maker (19 December 1992)

by Simon Reynolds

Fifteen years on, The Cure are post-punk's hardy perennial. Of all their peers, they're virtually alone in making it to stadium level without pandering or becoming a grotesque self-parody. And 1992 was another great year for the band, with the mega-selling Wish album and a mammoth world tour. In a rare solo conversation, Robert Smith talks about 'Wish', about The Cure's following, about the pressures of being at the helm of a Post-Punk Institution, and his own status as an icon.

ON 'WISH' AND BEING INFLUENCED BY YOUNG BLOODS LIKE MBV AND RIDE

"I definitely think it would have been a totally different record record if we'd had the same songs but recorded them at the time of Disintegration. But it was actually doing 'Never Enough' for Mixed Up that made us want to be a guitar band again. Porl Thompson's always been very guitar-oriented, he's got loads of old guitars and amps, and in the past, he's probably been constrained by the way I've liked things to be very minimal. But for Wish everyone played out a bit more. We also had in mind the way it feels live to play as a guitar band, it's so much more exciting. The album does sound current in one way, but in another way it sounds timeless. Because a lot of the references are to earlier incarnations of The Cure. 'Friday I'm In Love' reminds me of 'Boys Don't Cry'. That old-fashioned Beatles craft of the perfect pop song."

ON 'END', AND THE LINE 'PLEASE STOP LOVING ME, I AM NONE OF THESE THINGS'

"In one sense, it's me addressing myself. It's about the personal sometimes fall into. On another level, it's addressed to people who expect me to know things and have answers - fans, and on a personal level, certain individuals. And it has a broader idea, to do with the way you fall into a path, it just becomes habitual even though it's not really the way you want to be. Sometimes, whole relationships are based on these habits. It goes beyond my circumstances as a star, because I think a lot of people put on an act. I think I had it in the back of my mind when I wrote the song that when came to performing it on the tour, it would remind me each night that I'm not reducible to what I'm doing. I do need reminding. Because it's got to the scale now where I could quite happily fall into the rock star trip. It might seem like it's quite late in the day for it to go to my head, since we've been going so long, but our success has reached the kind of magnitude where it's insistent and insidious."

ON 'TO WISH IMPOSSIBLE THINGS'

"I do sometimes wonder 'What is there left for me to do?' At the same time, I never really had the burning ambition to achieve what I supposedly achieved. So it's more of a general feeling that there only appears to be so much you can experience. And a feeling of wanting to have the courage to break away from what I'm doing, with which I'm comfortable. I think maybe I should do something I don't feel confident about, to try to get back that sense of danger. But then I wonder if I really miss that danger. Do I really want to sacrifice my happiness for the chance of experiencing more, when I've already jeopardised my entire life many times just for the sake of experiencing things?

"Any desires I have left unfulfilled are so extreme there's almost no chance of them happening. But I would really love to go into space, I always have since I was little, but as I get older, it's less and less likely I'd pass the medical! The only things I wish for are the unattainable things. Apart from that, I don't really have strong desires, except on behalf of other people. Generally, peace and plenty. My wishes are more on a global level. 'To Wish Impossible Things' is specifically about relationships. The notion of three wishes, all through history, has this aspect where, if you wish for selfish things, it backfires on the third wish. But wishes never seem to take in the notion of wishing for other people, general wishes or wishes about interacting with other people. In all relationships, there are always aching holes, and that's where the impossible wishes come into it."

ON 'DOING THE UNSTUCK'

"I was going to say that my biggest wish was not to have to get up in the morning, and that's not strictly true, but there are days when I feel like that. It's like watching models saying that they've got a really glamorous life, and then you find that they can't eat what they want, they can't drink, they have to get up at five in the morning and go to bed by nine at night, and the truth is that they don't do anything glamorous at all except walk up and down the catwalk and wander about in front of cameras. It's one of those myths, but modeling is glamorous, because it looks like glamour. And sometimes, I think to myself I'm free, I don't have to get up, but that's not the case cos I'm always doing something. Sometimes there are days when I refuse to do my duties. And I think there should be moments in everyone's lives where they take that risk and say 'Oh, fuck it, I'm not prepared to carry on functioning.' I suppose that's a feeling you wouldn't really associate with being in The Cure. But then again there is a thread running through The Cure that's all about escapism."

ON NOT WAITING TO GROW UP

"I met some people recently and I guessed really wildly and inaccurately at their age. I thought they were in their forties, but they were only two years older than me, in their mid-thirties. They'd passed across the great divide. Some of it's to do with having children. It has a very definite effect. A good effect, for some, but it does bring with it a sense of responsibility. I don't know what it is, but it's inherent in more people that it's not. People seem to want to grow up. And when they have children, they play with their kids, and it reminds them how it was to be young. But when they have to answer the door, they revert to being grown-up. I don't see whey they can't continue being like a kid. Obviously you change as you grow old, you become more cynical, but there are people who manage to avoid that. I know a couple of people who are quite a bit older than me, but they are still genuinely excited by things. They do things and really get caught up in them. Children can do that, get caught up I on-productive activity, but it's harder and harder to do that when you get older. At least, not unless you take mid-altering substance, of course!"

ON THE CURE'S FOLLOWING

"I think our experience has now got so diverse that it seems weird to talk in general terms about what we represent to them. The Cure are liked by some people I don't even like! There's people who like us just because we do good pop singles like 'High'. There's other people who'd die for the group. When it gets to that level, people who are really caught up in the band, it's frightening to be part of it, because I know that we don't understand life better than those people. We represent different things to different people, even from country to country. Even to different sexes and to different age groups. Polygram commissioned a survey of Cure fans, because I've had this long-running argument with record companies about what constitutes our audience. The companies believe the media representation of The Cure audience as all dressed in black, sitting alone in their bedrooms, being miserable. And they were shocked at the actual breadth of the Cure audience. I don't know what we represent to them. I don't even know what The Cure represents to me! If I considered us in those terms, what we stand for, I'd be very wary about putting a song like 'Friday I'm In Love' on the album. We are a very selfish group."

ON THE BURDEN OF BEING AN ICON

"I feel sometimes like I'm crusading on behalf of something, and that is going to pin me down to something that I'd ultimately resent. I've been through that with Faith and Pornography, people waiting for me and The Cure to stand for something. All that nearly drove me round the bend. And I don't need any encouragement.

ON HIS 'LITTLE BOY LOST' APPEAL, AND STILL FEELING MORE LIKE A BOY THAN A MAN, EVEN AT THE AGE OF 33

"'Wendy Time' is the first time I've used the word 'man' in relationship to myself in a song. So it is seeping through into the music. Five years ago, the line in question would have been 'the last boy on earth'. I've always been worried about doing music past the age of 30, about how to retain a certain dignity. The vulnerable, 'little boy lost' side of my image is gradually disappearing. I'm in the unusual position of having four very close male friends around me in this group, I don't feel the slightest bit of inhibition around them. I've got more intimate as I've got older."

ON HOW THE CURE ARE STILL A PUNK BAND

"Living in Crawley, traveling up to London to see punk gigs in 1977, what inspired me was the notion that you could do it yourself. The bands were so awful I really did think 'If they're doing it, I can do it'. It was loud and fast and noisy, and I was at the right age for that. Because of not living in London or the other big punk centers, it wasn't a stylistic thing for me. If you walked around Crawley with safety pins you'd get beaten up. The risks involved didn't seem to make sense. So luckily there aren't any photos of me in bandage trousers. I thought punk was more a mental state.

"The first time we played in our school hall, we bluffed our way in by saying we are gonna play jazz-fusion, then started playing loud, fast music. And that made us a punk band, so everyone hated us and walked out, but we didn't care cos we were doing what we wanted. I suppose all that punk means to me is: not compromising and not doing things that you don't want to do. And anyone who follows that is a punk, I guess. But then, that could make Phil Collins punk, if he's genuinely into what he does!

"We've never really been bothered about confronting people. We've gradually become more accepted, just cos we've been around so long. We've upset a lot of people in the business cos we've shown that you can do things exactly how you want and be successful. Most confrontational gestures were so hollow that they're laughable. The KLF carrying machine guns at the British record industry awards - you just have to look at the front pages of any newspaper to put that kind of gesture in proper perspective.

There should be confrontation in pop, but I think people doing it often believe they're achieving a lot more than they actually are. The premeditated, Malcolm McLaren idea of confrontation is lamentable. Things are only really threatening if someone does something for its own sake and it happens to upset people. The only time we've even come close to that is the whole 'Killing An Arab' debacle. For a couple of days we made the national news in America. And it was the last thing in the world we wanted to get caught up in. Debating Camus on US cable television was totally surreal."

ON TRYING TO STAY AN ENIGMA

"It's very difficult, having been around for so long, a persona builds up around you that's continually reinforced despite your attempts to break away from it. It's like trying to fight you way out of paper mache, there's always people sticking bits of wet newspaper to you all the time. I conjure up in my mind figures like Jim Kerr or Bono, and I always have an image of what they represent. It might be really for away from the truth, but they're trapped in it. I often hear people say of write books about me and the group and they're completely at odds with how I think about us.

We do things from time to time that are mischievous, and in the videos we play around with caricatures of ourselves. But at other times, we're not really mischievous: that implies that we're doing things for nuisance value, and we never have. We can't win really: we're either considered a really doomy group that inspires suicides or we're a bunch of whimsical wackos. We've never really been championed or been hip, and so we've never really been treated as a group that stands for something, like say, Neil Young or The Fall have.

"It comes back to the idea that The Cure image is the non-image. We've been through every extreme, like the phase where we were sort of faceless in an archetypal early '80s way. Then four years later I was being slagged off for wearing too much make-up. Ultimately I can't take it too seriously. Through reading so many record reviews, I'm always staggered at the difference between what I'm listening to and what the critic thinks it's all about.

ON BEING A BOOKWORM

"I try and combat this feeling that I'm missing out on something very fundamental to that I should by now have realised, by reading ferociously. And I still come to the end of books that have been recommended to me by people I consider wise, and I always wonder 'Have I missed the point, or is this something that I knew anyway? I think it's really worrying, getting older, and not knowing anything more intellectually. I don't think I know anything more intellectually. I don't think I know anything more than when I was 15, except on experimental level. I only know things that I wish I didn't know. But I've never really craved wisdom. I enjoy the discussions we have in the group, everyone's well-read, the discussions can soar sometimes."

ON HIS SPLIT-PERSONA - HALF ART-ROCKER, HALF ORDINARY BLOKE

"I don't think it's two sides of my character, it's all of me. In the group, we have quite intense, emotional conversations about things. At the same time, we can go to the pub and get so drunk that I can remember how I got home. But I don't feel bad about it later, I don't think it doesn't fit with how I'm supposed to be. Equally, I wouldn't feel embarrassed if someone asked me what I'm reading at the studio, and I said Love by Stendhal.

I object to people who revel in either end of the spectrum and ignore the other aspect. People who only exist to go home the pub, of people who think 'Oh no, you can't watch football, it's just a pack of men kicking a ball around a field.' I would feel weird excluding one aspect cos felt it wasn't appropriate. It's all me."

Our first release of 2025 was announced today, featuring our very own Olga Wojciechowska, (Infinite Distances (2019), Unseen Traces (2020), and the 2022 collaboration with Scanner), alongside Tomasz Walkiewicz.

The Monoparts project was sent to me as unreleased material a few years back by Olga, and it was spoken of as something that would never see the light of day, due to the duo going their own ways.

It was put into rotation on 9128.live, and since then, I grew to love it so much, I made the steps to secure it as a release on ASIP.

In a dramatic departure, Olga unveils a new and unexpected side, debuting her haunting vocals—a delicate, spellbinding performance that recalls the golden era of trip-hop, and comparisons to the sounds pioneered by Tricky, Massive Attack, and Martina Topley-Bird.

"This album is like becoming one with the earth itself—feeling the rawness of the wood, tasting the earth in your mouth, and sensing the presence of ancient spirits. The music carries a deep, primal energy, like being part of the forest, with creatures watching you from the shadows." - Olga Wojciechowska

To complete the journey, ASC lends his signature touch with a stunning drum'n'bass reinterpretation, amplifying the album's nostalgic essence. Soothsayers emerges as a spellbinding ode to times gone by, in more ways than one.

Featuring artwork by Moon Patrol, with mastering and lacquer by Andreas LUPO Lubich, Soothsayers will be available on 12" maroon smoke-colored vinyl and Bandcamp on February 28th. Preorder is now available on Bandcamp and Space Cadets, with more stores to follow soon.

Save the Monday 24th for our listening party over on Bandcamp. RSVP here.

A 2018 piece for Stanford Live on Bowie's death and the art of the eulogy.

The night that the news went out that David Bowie had died, I was just finishing a book in which he was the central figure. On January 10th 2016, I was literally on the last pages of my glam rock history Shock and Awe when Twitter told me that this towering pop figure had fallen.

A mixture of emotions muddied my mind. Having labored for three years on the book, I felt like I had an unusual intimacy with Bowie, as if I truly understood his motivations - specifically that ache of emptiness that drove him in search of a succession of cutting edges, a desperate hunger for new ideas to kindle the creative spark within him. At the same time, having reached the end of my book, I felt oddly detached, as if I had finished with Bowie, or even - in some superstitious way - finished him off.

Born in Great Britain, but a resident of America since 1995, for me Bowie's passing was further entangled with growing feelings of nostalgia: he'd loomed over the Seventies, my childhood, just like the Beatles had dominated the Sixties. Bowie's songs were a perpetual presence on U.K. radio; his face appeared regularly on TV, especially on the weekly pop show Top of the Pops. From the entrancing strangeness of "Space Oddity", through the homoerotic intimations of "John, I'm Only Dancing", to the cross-dressing subversions of the promo video for "Boys Keep Swinging", Bowie had not only always been there, he'd always been startling. For many people across the world, but particularly for those who grew up in the U.K. during that era, Bowie's sudden non-existence felt like a part of the sky had suddenly vanished.

More ignoble thoughts intruded amid the grief. I did think, selfishly, "damn, there's going to be a flood of Bowie-related books rush-written, to compete with my own tome, over which I've toiled so diligently and protractedly." There was annoyance too, as it became clear that despite my exhaustion I would have to resume work immediately and write an extra closing essay to round off the book.

Ending Shock and Awe with Bowie peeved me because one intention starting out had been to put the man in his place just a little: I aimed to contextualise Bowie, reconstruct the culture and the rock music discourse out of which he'd emerged, while also elevating other artists now semi-forgotten but who at the time were considered his contemporaries and artistic equals (as well as often selling many more records than him, in fact). I hadn't wanted my history to become his story - but here was Bowie upstaging everyone again, insisting on being the last word, or at least the last subject for my words, in the Book of Glam.

Talking about upstaging - Bowie's death coincided with the Golden Globes, which meant that he knocked all the winners off the front page worldwide, outshone the world's stars with his own supernova. Including Lady Gaga - the figure who'd done her darnedest to be the Bowie of the 21st Century, and that night had won a trophy for her turn in American Horror Story.

As I returned reluctantly to my computer, I pondered how to approach the daunting task of summing up a man's life and work. All around, online and in print, teemed thousands of public tributes and private testimonials - a fiesta of remembrance, in which professional writers and fans alike competed to find fresh perspectives and idiosyncratic angles. Especially because my essay would have a longer shelf life, it felt like I should attempt to speak not just for my own feelings but for the larger community of people who had been affected by Bowie's existence. There were many notes being sounded in those weeks immediately after his death, but a prominent leitmotif was gratitude, tinged with self-congratulation. A sentiment crystallized sharpest in the widely circulated statement, mistakenly attributed to the actor Simon Pegg: "if you're sad today, just remember the Earth is over four billion years old and you somehow managed to exist at the same time as David Bowie." As is so often the case with the passing of a pop-culture icon - think of Prince - it felt like people were mourning themselves by proxy, coming to terms with the fading of their own time, and holding fast to the consoling belief that they lived through an exceptional era.

I decided to approach the essay as a eulogy, written on behalf of the gathered grieving, yet I would also try for something almost impossible: a honest eulogy. In other words, I would aim to be true to the insights about his character, motivations, influence and legacy that had emerged through writing the book (a verdict more ambivalent than you might expect) while still transmitting a sense of awe that someone so strange and ambitious could have moved within the humble domain of pop music. A sense of how improbable it all was, really - and how unlikely to happen again, despite the wishful efforts of figures like Gaga, or Kanye West, or Janelle Monae, to achieve something equivalent in terms of art-into-pop impact.

The root meaning of the word eulogy in Ancient Greek is "speak well." The funeral oration is meant to be a song of praise, and that means it almost inevitably becomes a whitewash, a lick of paint covering over the cracks and fault-lines. The death of someone is not the best time for airing the whole truth about that someone. Instead, just like the cosmetically-enhanced face of the dearly departed at an open-casket funeral, you are trying to fix the final and lasting image of that person as seen in their very best light. The mortician and the eulogist are in the same business really.

Amid the collective outpouring of grief and gratitude for Bowie's sonic and style innovations, his personae shifts and image games and the sheer drama of a career played out on the stage of the mass media, there was understandably scant inclination for a close examination of less wholesome or impressive sides of his work. Like that alarming phase in the mid-Seventies during which Bowie talked in fascist terms of the need for a strong leader and called for an anti-permissive crackdown on liberal decadence. Or all those credulous and indiscriminate flirtations with magic and mysticism that ran through much of his life (again reaching an unsightly climax in the cocaine-crazed years circa 1974-76). People likewise didn't dwell much on the long period during which Bowie's Midas touch failed him: the years of the "Blue Jean" mini-film, the Glass Spider tour, Labyrinth, Tin Machine and the beard… A period that if you were being honestly harsh constituted (give or take the occasional quite cool single) an unbroken desert of inspiration and direction that lasted two whole decades: 1983 to 2013, from the last bars of Let's Dance to the first of The Next Day. I distinctively remember that through much of that time, Bowie dropped away not just as figure who frequented the pop charts or commanded attention, but even as a reference point, something that new bands would cite as a model or touchstone.

It makes sense that the least compelling phases or most questionable aspects of Bowie's life wouldn't figure in the immediate post-mortem reckoning. Speaking ill of the recently dead is not a good look. But something of Bowie's complexity - his flaws and his follies- got written out with the concentrated focus on his genius achievements, personal charm, and acts of generosity.

Maybe it's my age, but I'm sure I can't be alone in feeling that important pop cultural figures are dying off at an accelerated rate. Then again, perhaps this is an illusion created by the sheer overload of coverage triggered by each passing: the internet and social media create so much opportunity and space for remembrance, and the profusion of outlets fuels a competition to offer ever more forensically deep or differently angled takes on the departed artist. There seems to be a widespread compulsion felt by civilians as well as professional pundits to make an immediate public statement: the news goes out that an icon has gone and Facebook teems with oddly official-sounding bits of writing that often read like obituaries with a slight first-person twist.

Sometimes I've felt that people protest a little too much about their intense relationship with the extinguished star. Where did all these people come from with their lifelong and surprisingly deep acquaintance with the oeuvre of Tom Petty? Who knew there were people who bothered with the three George Michael albums after 1990's Listen With Prejudice Vol.1? And surely I'm not the only one out there who - while fully cognizant and wholly respectful of the world-historical eminence of Aretha Franklin - only ever owned her Greatest Hits and - if I'm honest - really only ever craves to hear "I Say A Little Prayer"?

The truth of pop for most people, I suspect, is that we use the music to soundtrack our lives, but in a fairly fickle, personal-pleasure attuned way, and - apart from a few formative exceptions, the kind of teen infatuations that shape worldviews - we seldom engage with the totality of an artist's work and life. Tom Petty, for me, boils down rather brutally to the urge to turn up the volume when "Free Falling" and "Don't Come Around Here No More" come on the radio (in other words, he's on the same level as The Steve Miller Band and Bachman-Turner Overdrive). Unfair or not, George Michael reduces to a couple of nifty Wham! singles plus "Faith" and "Freedom! '90". A few moments of unreflective pleasure in the lives of millions of casual listeners is no small achievement, although it wouldn't have been enough for these guys, who craved to be Serious Artists on the level of those they venerated: Dylan and the Byrds, for Petty… someone like Stevie Wonder or Prince, for Michael. No amount of earnest reassessment or auteurist reappraisal could persuade me to dig deep into their discographies for those lost gems tucked away on Side 2 of a late-phase album.

You'll get no argument from me about Bowie, of course: career doldrums and dodgy opinions aside, he's as major an artist as rock has produced, worthy of taking as seriously as anybody (which is why the fascist flirtations and the half-baked occultism are troubling, as opposed to something you'd laugh off in a lesser figure). And Bowie also did what almost no fatally ill or otherwise declining pop star has ever managed, which is to go out on an artistic high. Beyond their musical daring and desperate expressive intensity, Blackstar and the videos for "Lazarus" and the title track made for a fitting last statement because of the sheer care that went into them. This was so utterly characteristic of Bowie and the way he went about things. Who among us - facing the final curtain, sick in body and frail of spirit - could have summoned the obsessive energy and psychic strength to meticulously craft their artistic farewell to the world? Who, confronting oblivion, would have been so concerned about how they looked and sounded at the end? Only Bowie.

As I found writing Shock and Awe, the beginning of Bowie's public life was faltering, a series of false starts and fumbled career moves. It took Bowie eight years of dithering and stylistic switches to really become a star. In contrast, the closing of his career was immaculately executed. What some sceptics always regarded as his core flaws - cold calculation, excessive control - triumphed at the end. Bowie organized a grand exit so elegant that it fixed forever our final image of him, rendering all eulogies superfluous.