You think of Sounds and the things that spring to mind would be Oi! and Bushellism, and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. And maybe if you knew your British rock paper history, you would also think about Jon Savage and New Musick, and the "grey overcoat" Fac-loving thing associated with Dave McCullough, at least until he flipped for Postcard and his own version of poptimism.

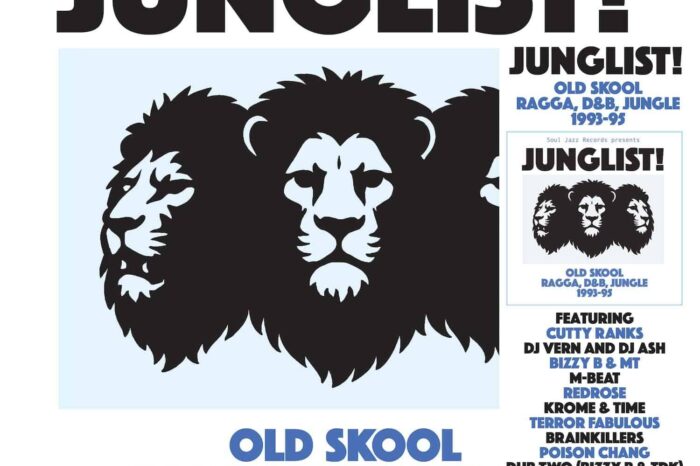

But alongside all that - the many flavours of ROCK - Sounds consistently covered reggae and dancehall. Put Jamaican and Black British artists on the cover.

(They also covered funk and soul, did pieces on early rap and hip hop).

NME was probably even better at covering these areas, but Sounds did a creditable job.

Especially considering this was verily the Dark Age of Rockisme. Or so we are told.

A lot of the late '70s coverage is coming from Vivien Goldman, before she jumped to first Melody Maker and then to NME. But there were other writers who kept it going deep into the Eighties, including Jack Barron and Edwin Pouncey.

And not just the roots-rock-rebel stuff, they also covered reggae at its poppiest - lover's.

Even Gaz Bushell wrote a bit about reggae now and then

Sweeping up the mince pie crumbs and taking down the tinsel, while feeling one-sherry-too-many green-about-the-gills - that's yours truly the day after the parish hall party celebrating 20 Years of Ghost Box.

The anniversary celebration came about when a light bulb went off above my head and I realized that I'd extravagantly commemorated twenty years of Creel Pone earlier this year but clean forgot about my other favorite record label of the 21st Century, Ghost Box. The two imprints seemed linked in my mind as heroic projects - both in their different ways manifestations of archive fever, the disinterment of buried futures.... and sources of immense ongoing pleasure for this listener.

My feelings about Ghost Box are expressed best in this thing I wrote for the 10th Anniversary in 2015.

Twenty years - goodness me, how time has flown by! Two whole decades since me and the late Reverend Fisher started rambling on about hauntology (although of course the entity had been taking nebulous form for a goodly while before its christening).

Chiltern Radio's Emilie Friedlander and Andrea Domanick kindly invited me to chat with them about the anniversary for their show Cujo (short for The Culture Journalist) . You can eavesdrop on the witterings over here.

Further musings on this merry-melancholy subject at the end of this newsletter, but first some new news - activity in the parish.

A bursting hamper of Moon Wiring Club music - the double-CD / double-LP Gruesome Shrewd and a cassette, Grisly Exaggerated - across which Ian Hodgson develops a new sound, at once recognisably MWC and a defamiliarizing extension. Avail yourself of the "Grisly Bundle" at his online shoppe and get a taster with this film below.

Trying to capture its qualities for myself, a couple of phrases sprung to mind...."Time becomes a quicksand" is one, and the other is "stretchy". As it happens, Ian himself uses the phrase "endless elongation" in the release-rationale below.

These tracks reminds me of the process by which Brighton or Blackpool rock is made: a thick slab of taffy gets extruded out to enormous length, in the process thinning out while still retaining its internal patterning. It's the vocal element, more pronounced and grotesquely deformed than ever, that forms the "lettering" inside the stick of rock that is each sprawling track on Gruesome and Grisly.

As it turns out, the idea of tooth-enamel-eroding souvenir treats bought at the seaside is a suitable thought given that the albums are loosely inspired by coach tours and the sensation of temporal suspension experienced while on holiday. Take it away, Ian:

"One of the main aesthetic influences was what I describe as 'Coach World' ~ that feeling on a holiday (or long journey) that you've got to spend 18 hours on a coach. At first you think 'I'm going to snap' but then after 3 hours you get into a different rhythm and before long (after 8 hours) you kind of can't remember what life was like before you started the journey ~ hence entering Coach World. What I wanted was music that has something of that endless elongation vibe. Initially daunting, then meditative, then you don't want to leave and have to listen again....

Another aesthetic influence was the idea of Holiday Memory ~ a fleeting moment of a holiday situation (going around an art gallery for example), where you can remember with clarity (or what your brain thinks is clarity) a specific moment (the angle of the walls, how the lighting looked, spotlights on glass, colours maybe scents or what you were feeling) forever hightened in your mind in a specific way (because you are on holiday) but you have little or no memory of what preceded / succeeded that moment. So you end up with a loop of thought, or a series of loops as a memory of a holiday from 20, 30, 40+ years ago. Over time they might not all even be from the same holiday.... This concept was something that kept popping into my mind as I assembled the music, sort of 'bursts of heightened memory looping'.

"Sonic Procedure wise, I was getting bored of limited melodic chord changes and wanted something that had a bit of distance from what my standard compositional impulses were. Essentially the majority of the music is comprised of micro-samples (like a snap blast of fuzzy background music on a VHS tape documentary c1982) that are then cleaned up a bit and subjected to endless processes (re-sampling is apparently the key word here). After doing this for several months I had a substantial wonky library of component tune elements that were then deployed in the guiding service of the Gruesome Shrewd package holiday aesthetic.

What I found was that generally the tracks fell into 3 styles ~

a) Sludgy Psyche Rock

b) 80s Corporate Corroded

c) Ambient Slurry (naturally there was also a judicious application of disembodied voices).

I suppose you could say this sort of sound world is Chopped + Screwed (which does sound a little like Gruesome Shrewd) but whereas (in my non-expert knowledge) C&S tends to have that nice thick syrupy sound + big bass + distortion, I'd say there's something different going on with GS/GE even though some of the production techniques would be fairly similar. It's sort of elongated chewing toffee bar mids rather than cough syrup mixture lows.

Compositionally I wanted something that sounded different to the more DAW / Electronica aspects of some MWC stuff ~ 'here are the beats / here goes the bass / that melody works as a chorus / tighten up that bit / move the last bit to the beginning as it has a better hook' etc. When putting these tracks together, quite often I went against my instincts and instead of tightening things up, deliberately left things more loose and allowed elements to play out / loop for longer...

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Coaches - specifically the rippled patterns of rain streaking down the windows of a coach in motion - is one of the mental images that often comes to mind when listening to the music of Lo Five. Another is the foreshortening effect on your visual range caused by light drizzle, a muffling of distance. Something about the grey-scale shimmer summons those mundane-mystical moments where boredom and bliss are so very close indeed.

There is a new Lo Five record - Superdank, released on Lunar Module, a CD-oriented imprint of Castles in Space - and it pulls me into its paradoxically inertial motion as irresistibly as ever. Slipping Time's moorings again....

Release rationale:

Lo Five is as proud as he is anxious to present SUPERDANK, a CD album packed to the green gills with heavy dubs for sleepy schlubs.

SUPERDANK is ostensibly presented as a collection of hardware stoner jams, structured in the form of an hour long edible-induced psycho-narrative, taking the listener on an aural voyage - kicking off at pleasant buzztown, calling past existential paranoiaville, then landing back in the relative safety of sofaborough in time for tea and crumpets.

But what is SUPERDANK? What does it mean?

If we were were inclined to illustrate the vibe, we'd say it's along the lines of:

• Forgetting you had an A-level exam because you were busy making the world's largest hash brown

• Having a panic attack in the shower because you couldn't gauge how hot the water was

• Claiming to have invented the story to The Matrix before watching The Matrix

• Using the pages of a bible for cigarette paper after running out of Rizlas

Is SUPERDANK a flimsy concept designed to package a bunch of disparate tracks we weren't sure wether to release or not? Or is it more of a subconscious collective fugue state, woven into the very fabric of our confused mental substrate? Maybe it's both? Who cares?

In either case draw the blinds, turn off your mobile and settle in for a trip you'll potentially regret forever, because it's time... for SUPERDANK...

Lunar Module is thrilled to present the latest album from Wirral based sonic alchemist Neil Grant, better known as Lo Five - a record that feels like it was beamed in from a parallel dimension where melody and madness hold hands.

In an era dominated by algorithmic predictability, Lo Five remains that rarest of artists: a producer whose music is unashamedly strange yet somehow impossibly tuneful. It's the sound of a Commodore 64 dreaming it's a jazz orchestra, or a broken music box trying to remember a rave from 1993 - familiar enough to hum along, alien enough to make the hairs on your neck stand up in delighted confusion.

Beyond the speakers, Neil Grant is a quietly heroic figure in the UK electronic underground. The time he pours into supporting fellow artists - organising events, mentoring newcomers, championing overlooked talent - make him as vital a community builder as he is an innovator in the studio.

This new Lo Five album is more than a collection of tracks; it's a reminder that electronic music can still surprise, unsettle, and seduce in equal measure. It's strange. It's tuneful. It's essential.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

American exchange student Daniel Lopatin has a fab new album out, Tranquilizer.

Over at Line Noise, though, Ben Cardew invokes conceptronica in trying to explain why's he not feeling this new Oneohtrix Point Never record.

Although tickled by this idea that I danced myself right out the womb, I have to do whatever the opposite of co-sign is here: partly because I don't generally find Dan's conceptual apparatus to be overbearing, it works more as a bonus supplement for the listener, but also because I loved Tranquilizer on first listen, as a simple flood of aural pleasure, no cerebration required. (I also don't think Oneohtrix has ever really been in the business of making people dance, so it seems an odd expectation). The conceptual aspect seem to work primarily as a germinal spur for the artist. In this case, the procedure involves sample CDs from the 1990s as a source that is then put through a series of processes - sounds connotative of luxury, relaxation, high-quality, are then tesselated in ways that are weirder and more abstract than their original intended function, but retain the aura of polish and professionalism

There seems to be a spectrum of ways artists in this approximate area operate. Some have a defined framing concept from the start (The Caretaker, or Debit), others work with a procedure or an idea of what the starter material is going to be (restriction, or focus, as the mother of invention). Some (Ghost Box for example) have a mood board, a constellation of musical and non-musical reference points and coordinates that give the project its consistency without overdetermining it. And then others still grope about in the formless dark, molding and grappling without any premeditated notion of where they are going, following intuition and instinct until a direction or shape emerges (I imagine this is how Autechre go about it). In the end, it doesn't really matter - the outcome is all that counts.

^^^^^^^^^^^^

Up at the Insitute, there's been a flurry of archival activity.

Notably Jean-Michel Jarre's very vaporwave looking if not sounding experimental electronic album of 1972, Deserted Palace

And also collations of work by Bernie Parmegiani and by ex-wife Jean Schwarz

The Bernie collection includes his marvelous music for this marvelous animation by Piotr Kamler, which almost singlehandedly propelled me into the (once fevered, now somewhat dormant) obsession with experimental animation as fitfully still expressed at the blog Dreams, Built By Hand and its attendant ever-growing playlist, which would take at least a week to watch through. You'll notice that "L'araignéléphant" - it translates as "The Spider Elephant" - is the first film at the top of that playlist.

Another archival release of recent years, now itself reissued in spiffed up form, comes from our Irish affiliates the Miúin label: Kilkenny Electroacoustic Lab Volume 1 now comes with a book and a poster.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Ghost Box, I'm told, is actually in a state of hibernation these days, with one driving force occupied with other non-sonic activities and the other determinedly pushing into different areas with his Belbury Music imprint. The most recent release is Runner's High by Pneumatic Tubes (an alias for Jesse Chandler of Midlake /Mercury Rev) - a concept album about running.Intriguing murmurs reach my ears of the mood board for forthcoming Jim Jupp music - Bill Nelson, Clannad, Japan, Axxess (whoever the eff they may be)... fretless bass, ebow guitar, and the 82-84 transition moment between analogue and clunky early digital. I do not know if it will be as Belbury Poly or some other identity.

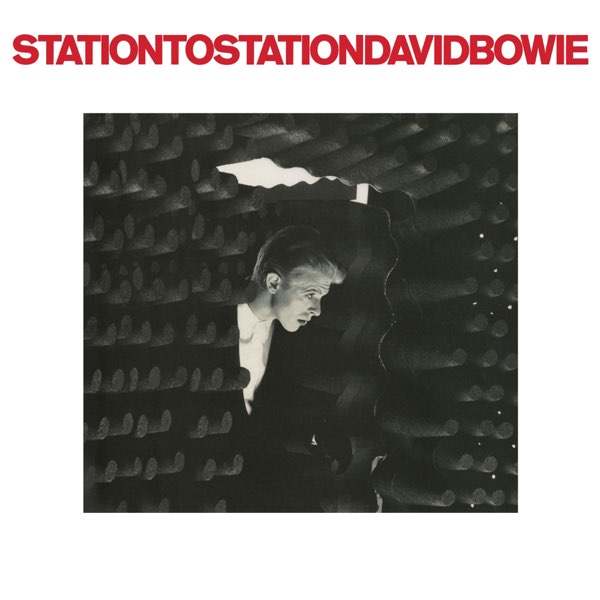

There is a parallel between the evolution of Ghost Box and my favorite labels of the '90s, Moving Shadow and Reinforced: sampladelic producers who gradually get into playing hardware analogue synths, electric and even acoustic instruments. That maturing into musicianship generated some wonderful dividends in both cases, but for me the core of hauntology, as it was with hardcore jungle, is the sorcery of sampling: chunks of dead time reanimated. Ardkore and hauntology are both wyrd British mutant forms of hip hop.

The collage aspect is one reason why Mark Leckey's Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is the supreme visual artwork counterpart to what Ghost Box and Moon Wiring Club and The Caretaker would later do. The film's audio aspect also prefigures hauntology (it was made in 1999). Fiorucci is also a convergence point - alongside Caretaker's The Death of Rave - between the Moving Shadow/Reinforced realm and the Ghost Box et al world. (Clean forgot that the Fiorucci audio-score actually came out on a imprint called The Death of Rave). Dream English Kid 1964-1999, although based around a different memoradelic mood board, is also in this zone of revenant reverie as memory work.

We really should arrange a showing of both films at the Film Club.

Let me wind this newsletter up with my Top 20 Ghost Box releases (including a couple that are technically on another label but still count as GB releases in my mind)

1/ The Focus Group - hey let loose your love2/ Belbury Poly - The Willows3/ The Advisory Circle - Other Channels4/ Roj - The Transactional Dharma Of Roy5/ The Focus Group - Sketches and Spells 6/ The Advisory Circle - Mind How You Go7/ ToiToiToi - Vaganten8/ Eric Zann - Ouroborindra 9/Belbury Poly - From An Ancient Star10/ Broadcast and The Focus Group Investigate Witch Cults of the Radio Age 11/ John Foxx and the Belbury Circle - Empty Avenues 12/ Beautify Junkyards - Cosmorama13/ The Focus Group - Electrik Karousel 14/ The Advisory Circle - From Out Here 15/ Belbury Poly - Farmer's Angle16/ Children of Alice17 / The Focus Group - Stop Motion Happening with the Focus Groop18/ Beautify Junkyards - Nova 19/ ToiToiToi - Im Hag20/ Beautify Junkyards - The Invisible World of

And then in a special category of its own

Paul Weller - In Another Room (mainly just for the sheer shock surprise of its existing and him being a fan but a creditable effort)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Suddenly remembered that it was Julian and Jim who did the early version of this very circular, cranking it out back then on a hand-operated mimeograph. I can find barely any proof of its existence online but I know I have a paper-and-ink copy somewhere: The Belbury Parish Magazine.

- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

- The half-lives of hauntology continue - word reaches me of this book, out on Reaktion next summer.

- By my count, this is the fourth substantial book on the H-zone (not counting the A Year in the Country ever-growing seriess of volume, or the 'pastoral horror' microgenre or 'scarred by 70s kids tell'-sploitation subset).

- I suppose the first would be our dear lost boy's Ghosts of My Life.

I had a very interesting and jolly chat with Adina Glickstein for the arts magazine Spike on the subject of nostalgia and retrokultur, touching on many topics including techbro futurism and the Zone of Fruitless Intensification.

The whole Spike issue is themed around nostalgia and related subjects and well worth a peruse.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

I suppose it's nice to have done a book that enjoys a half-life or two... it is surprising how often I still get asked to comment on these sort of themes: retro-paralysis, cultural stagnation, hauntology...

I don't mind, but in truth my mind has moved on to other preoccupations... mainly the ideas surrounding the new book, due out in June next year.

Which as it happens has a completely different perspective on "the rhetorics of temporality" than Retromania.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Keeping the retrochat going have been other writers with books that either extend the polemic or refute it....

In the first camp, there's W. David Marx with Blank Space: A Cultural History of the 21st Century, for which I gave this blurb:

"The first quarter of the 21st Century had a paradoxical feeling - so much happened and yet nothing happened at all. A triumph of forensic research and pattern recognition, Blank Space cuts through the bustle and the babble, makes a senseless time make sense. W. David Marx diagnoses the malaise and even proposes a course of treatment. This is a book that's fun to agree with and even more fun to argue with."

Here is a fairly positive response to Marx's argument from Celine Nguyen at Asterisk and a far less friendly take from Emily Watlington at Artnews. Here's an extract at The Atlantic.

(The one thing I didn't get with Marx's book is why he titled it Blank Space, which to me seems like either a positive image - possibility, an open frontier - or a neutral one. As a trope of barrenness in re. the first 25 years of the 21stC it doesn't quite compute for me).

As regards the counter-argument, the Full Space perspective - "these be years of plenty, innovations up the wazoo, you just need to gouge loose the wax clogging up your ears, O geriatics" - there's the fairly recent book Songs in the Key of MP3: The New Icons of the Internet Age by Liam Inscoe-Jones.

Here is a wide-ranging discussion Inscoe-Jones had with Chal Ravens at Tribune a few months ago, and which has suddenly jumped out from behind the paywall. It's title is Has Pop Finally Eaten Itself? (Variations on that trope certainly have eaten themselves by this point!)

The piece's url, I note wryly, includes the words "after-retromania".

Would that we were! In both senses of the word - the discourse, and the underlying phenomenon itself.

Clearly there's enough evidence - currently, but probably at most moments in the history of pop culture, apart from very obvious surge phases like mid-Sixties or punk/New Wave - that could be marshalled to sustain either argument.

There's always a ton of lame stuff around - revival, retread, remake, etc.

Equally, you can always point to people doing cool things in music - even during the years when I was writing Retromania, I never had any trouble coming up with a substantial end-of-year list of music I liked and thought was doing interesting things. Inventive, if not quite innovative.

The problem is more on the level of: what is the most that you can imagine happening with this cool / clever / inventive / conceivably even innovative music? Is it going to break out all across the surfaces of everyday life? Shake things up?

I would say "is it going to change the sound of the radio?" (thinking of Timbaland, or New Wave, or psychedelia - the instantiation of a new sonic template on a culture-wide basis).

But radio isn't a thing anymore. Who listens to the radio?

That is the big structural problem, which Ravens and Inscoe-Jones touch on in their dialogue. Monoculture still exists, but its mechanisms now - TikTok etc - agitate against anything lasting or substantial.

In terms of "change the sound of the radio" - the last time that happened as far as I can tell is the Auto-Tune trap moment. (Which is the last moment I personally listened to the radio regularly). (And which was also my kind of "psychedelic rap" as opposed to the stuff Inscoe-Jones reps for - Danny Brown etc).

But then again.... doesn't it all seem so trivial, as something to be concerned about, next to what's happening in this country, and in too many other places around the world - including the UK? Political retromania is the true nightmare.

Bevis Frond addresses the Anxiety of Influence in song - appropriately using the most Oedipus Complex-obsessed, Norman O.Brown-stanning man in rock, Jim Morrison, although it's a different Jim who forever shadows his (re)creative efforts.

"I took an album from the ancient unit

And I walked on down the hall

"Jimi, I want to kill you"

He stood before me in a vision

With treasured secrets of the blues

A voice rang out from battered speakers

"You are not fit to shine my shoes".

Jeff Lynne, virtually a Bloomian archetype of the "weak rocker", here on "Beatles Forever" fesses up to his unrecoupable artistic debts. But then chickened out and didn't release the track.

Key couplet:

I try to write a good song, a song with feel and care

I think it's quite a good song, 'til I hear one of theirs

Full lyric:

Beatles forever

Da-da-da, da-da-da, da-da

There's something about a Beatles song, that lives forevermore

The beauty of the harmonies, the sound of the Fab Four

All their music will live on and on (John 'n' Paul, George and Ringo)

They really taught the world to sing (She came in through the bathroom window)

Beatles forever, "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"

Beatles forever, "All You Need Is Love", yeah yeah yeah

Beatles forever, "I Wanna Hold Your Hand," wooh

Beatles forever, "Hey Jude" and "Revolution" (number nine)

'Cause when you feel the beat, you've gotta move your feet

You get the rhythm and blues, and a pretty tune

Rock and roll eternity, that started out as Merseybeat

I try to write a good song, a song with feel and care

I think it's quite a good song, 'til I hear one of theirs

Makes you wonder how they did it (John 'n' Paul, George and Ringo)

I wish I knew the secret, yeah yeah yeah (She came in through the bathroom window)

Beatles forever, "Strawberry Fields Forever" and ever

Beatles forever, "Nowhere Man" and "Penny Lane", yeah yeah yeah

Beatles forever, "Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds"

Beatles forever, "Get Back" and "Yesterday"

'Cause when you feel the beat, you've gotta move your feet

You get the rhythm and blues, and a pretty tune

Rock and roll eternity, that started out as Merseybeat

All the children sing

Beatles forever, "Please Please Me", "Eleanor Rigby"

Beatles forever, "I Am The Walrus" (yeah yeah yeah) goo-goo g'joob

Beatles forever, "She Loves You", ooh, "Day Tripper"

Beatles forever, "Eight Days A Week", "Magical Mystery Tour"

'Cause when you feel the beat, you've gotta move your feet

You get the rhythm and blues, and a pretty tune

Rock and roll eternity, that started out as Merseybeat

Ah ah-ah-ah-ah, ah-ah ah-ah, ah-ah-all-ah

Ah, feel the beat, ah-ah-ah-ah, gotta move your feet ah-ah ah-ah

Rhythm and blues, ah-ah-ah-ah, pretty tune

Ah, rock and roll, ah-ah-ah-ah, eternity, ah-ah ah-ah

Started out, ah-ah ah-ah, as Merseybeat

Beatles forever

Beatles forever, yeah yeah yeah

Beatles forever

Just about the most hauntological thing I have ever seen, and it was made in 1962!

This BBC short film, titled "The Lonely Shore" and produced under the aegis of the program Monitor, imagines a team of researchers visiting the deserted wasteland of the British Isles centuries after an undetermined and civilization-ending devastation, and trying to reconstruct a sense of this lost culture from archeological fragments - furniture, plastic artifacts, appliances, vehicles - to which are often attributed religious significance.

Keeping it haunty, there's some nice and eerie Radiophonic Workshop and Henk Badings electronics on the score.

And then there's grave and witheringly supercilious upper class voiceover - mordantly speculating about the spiritual emptiness that rotted out this culture from within, a loss of purpose, vitality, connection to Nature - which has the feeling of a classic Public Information film.

As for the text itself, there are suggestions that the author is familiar with Nietzsche (Uses and Abuses of History, the Last Man - "we can feel only pity for these last men and women", goes the "Lonely Shore" voiceover) and Oswald Spengler (patternwork, Decline of the West).

There are even a few proto-Retromania touches, which again is pretty good going for 1962.

The film's beachscape setting, with the Jetsam of Time - the mystifying and opaque salvage - arrayed in orderly and symmetrical patterns, recalls the Easter Island statues, certain tableaux from Surrealist paintings, and the post-catastrophe vistas of J.G. Ballard eerie early short stories and novels.

I wonder also if whoever wrote it was a fan of Olaf Stapledon, specifically Last and First Men.

There's also a touch too of H.P. Lovecraft and At the Mountains of Madness.

One of those finds that seem too good to be true somehow but it is via the BBC Archive.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Informational lowdown from Ian Holloway at Wyrd Britain:

"Written by Jacquetta Hawkes, filmed by Ken Russell and with commentary by Tony Church, this fabulous little film was one of 21 that Russell made for the fortnightly BBC arts programme 'Monitor' between 1959 and 1962.

"The entirely fascinating Hawkes - the first woman to read for the Archeology & Anthropology degree at the University of Cambridge, co-founder of CND, gay rights campaigner & wife of novelist J.B. Priestly - provides a text that is as cutting as it is blunt, that satirises both the language and assumptions of her own disciplines and the cosy absurdities and consumerist excesses of British life in the early 1960s. "

Hawkes was an archaeologist, among other things, which fits the framing of "The Lonely Shore"

Wordsworth, from the Prelude to the Lyrical Ballads, written and published in 1800

The Seventeenth Century is barely over and here is William, complaining about what we would think of as the doomscroll or media overload: "the great national events which are daily taking place... a craving for extraordinary incident, which the rapid communication of intelligence hourly gratifies", stirred up in the hearts and nervous systems of those who live in cities.

"Hourly gratifies" - how often did broadsheets come out in those days? Perhaps he's talking about gossip, rumors...

And then William's other complaints about degraded entertainments and hyperstimulation - "frantic novels, sickly and stupid German Tragedies, deluges of idle and extravagant stories in verse". He could be talking about TikTok and Reels, influencers and Love Island, videogames and franchise blockbusters.

In the Prelude, he proposes Nature and pastoral life as the remedy, a soul-recentering restoration, a resetting of the overclocked sensibility. Again, very much like wellness and meditation and silent retreats today

"An almost savage torpor" - I'd put that on a T-shirt. That is my existence, distilled.

Interesting also to learn from the Prelude that Wordsworth - whose poetry today seems like proper fancy stuff - was in fact aiming to write in the language of the common man, plainspoken, earnest, stripped of all affectations, circumlocution, ornamentation and other flashy flourishes

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

With tranquil restoration:—feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

an excerpt from Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798

_-_The_River_Wye_at_Tintern_Abbey_-_PD.46-1958_-_Fitzwilliam_Museum.jpg)

I wonder if Wordsworth would have approved of this tribute?

Busy bee

Buzzing all day long

What's the hurry?

There's surely something wrong

I can't rest while the sun and the stars are so bright

'Cause your friends are picking flowers

Take away all my light

But you see busy bee

It's all for love

People pick them

You lick them all for love

Lalalalala...

She was a virgin, of humble origin

She knew of no sin

Her eyes as bright as the stars without light

Spent all the night

Someone asked me what I meant by this term….

"Hyperstasis" is a concept I came up with after listening to a bunch of new electronic dance albums that had been hyped by music journalists, and having this mixed response: being quite impressed by the intelligence and diversity of the music, while ultimately being dissatisfied because nothing on the record ever really felt to me like it was "totally new" or "the future". (Which is the sensation I got all the time from electronic dance music in the Nineties, that the music was hurtling into the future and mutating wildly into all kinds of unprecedented forms). Often I concluded that the artists had managed to avoid being indebted to a single source by being diversely derivative.

Hyperstasis is a paradox, similar to the idea of "running on the spot", or the hamster who cycles endlessly and frenetically on his wheel. The "hyper" element is the way that the music, across the whole of an album but sometimes also within any given track, shuttles back and forth across a kind of grid-space of influences and sources. It is recombinant without ever quite innovating. It moves at a great speed and with great fluency within terra cognita, the sonic territory of the already known. But it never quite manages to push into the unknown and take the listener "out there".

Hyperstasis is a condition that afflicts individual artists and pieces of music. But it is also a condition that can trap an entire genre or field of music. It is not such a terrible state of affairs: good records still come out, often a lot of them. Hyperstasis is not a state of entropy and inertia so much as a febrile stage that follows a period of earlier creativity, which generated a lot of material to be reworked and recombined. But the suspicion is that the frenzy of hyperstasis is what precedes a final collapse.

^^^^^^^

Although I have no recollection of taking it from somewhere or even seeing it before I started using it circa 2009-10… it seemed like a word that would have to have been invented for some other purpose. I did look it up once and seem to recall it had some very specific meaning in physics or maybe finance.

It feels to me to have some vague kinship with stagflation, but there isn't a direct correlation or analogy - more that both words describe something oxymoronic, "shouldn't be happening", worst of both worlds syndrome.

~

Historians of retro concur that the first time "retro" was used in its current way was in France in the early '70s, with the phrase mode rétro - the retro style - to describe a spate of historical films about France during World War 2, which then sparked a 1940s fashion revival.

Here is an interview with Michel Foucault from July 1974 in which he caustically castigates the trend. It's from Cahiers du Cinema and it's titled ANTI-RETRO' and Foucault's interlocutors are Pascal Bonitzer and Serge Toubiana. Translated by Annwyl Williams. Disappointingly the word "retro" never passes the lips of MF himself. In truth, the discussion is not really about retro as we would understand the term - depthless and dehistoricized duplication of the past - but about historical revisionism and popular memory.

CAHIERS: Let's take as our starting point the journalistic phenomenon of the 'retro style', One might simply ask: How is it that films like Lacomhe Lucien or The Night Porter are possible today? Why are they so immensely popular? We think there are three levels that ought to be taken into account. First, the political conjuncture. Giscard d'Estaing has been elected. A new type of relation to politics, to history, to the political apparatus is being created, one that indicates very clearly - and in a way that is plain to everyone - the death of Gaullism. We therefore have to see, in so far as Gaullism remains very closely associated with the period of the Resistance, how this manifests itself in the films that are being made. Second, how can bourgeois ideology be mounting an attack in the breaches of orthodox Marxism - call it rigid, economistic, mechanistic , whatever you like - which for a very long time has provided the only grid for interpreting social phenomena? Finally, where do militants fit into all this, since militants are consumers and sometimes producers of films?

What has happened since Marcel Ophuls's film The Sorrow and the Pity is that the floodgates have opened. Something which until then had been completely suppressed, that is to say banned, is being openly voiced. Why?

FOUCAULT: That can be explained, I think, by the fact that the history of the War and what happened before and after the War has never really been inscribed in anything other than wholly official histories. These official histories are basically centred on Gaullism which, on the one hand, Was the only way of writing that history in terms of an honourable nationalism and, on the other hand, was the only way of casting the Great Man, the man of the right and of outdated nineteenth-century nationalisms, in a historical role.

It boils down to the fact that France was exonerated by de Gaulle, and on the other hand the right - and we all know how it behaved at the time of the War - found itself purified and sanctified by de Gaulle. Suddenly the right and France were reconciled in this way of making history: don't forget that nationalism was the climate in which nineteenth-century history (and especially its teaching) were born.

What has never been described is what happened in the very depths of the country from 1936 on, and even from the end of the First World War to the Liberation.

CAHIERS: So, what has perhaps been happening since The Sorrow and the Pity is that the truth is making its return into history. The question is whether it's really the truth.

FOUCAULT: That has to be linked to the fact that the end of Gaullism has put a stop to this justification of the right by de Gaulle and the episode in question. The old Petainist right, the old collaborationist, Maurrasian and reactionary right which camouflaged itself as best it could behind de Gaulle, now considers itself entitled to produce a new version of its own history. This old right which, since Tardieu, had been disenfranchised historically and politically, is coming to the fore again.

It supported Giscard explicitly. It no longer needs to wear a mask, and so it can write its own history. And among the factors that explain Giscard's current acceptance by half the French (plus two hundred thousand), one mustn't forget films like those we're talking about - whatever the film-makers actually intended. The fact that all that has actually been shown has allowed the right to re-form along certain lines. In the same way that, inversely, it's the blurring of the distinctions between the nationalist right and the collaborationist right that has made these films possible. It's all part of the same thing.

CAHIERS; This piece of history is therefore being rewritten both in the cinema and on television, with debates like those on Dossiers de I'ecran (which chose the theme of the French under the Occupation twice in two months). Film-makers considered to be more or less on the left are also apparently involved in this rewriting of history. That's something we have to investigate.

FOUCAULT: I don't think things are that simple. What I was saying a moment ago was very schematic. Let me continue.

There's a real battle going on. And what's at stake is what might be roughly called popular memory. It's absolutely true that ordinary people, I mean those who don't have the right to writing, the right to make books themselves, to compose their own history, these people nevertheless have a way of registering history, of remembering it, living it and using it. This popular history was, up to a point, more alive and even more clearly formulated in the nineteenth century when you had, for example, a whole tradition of struggles relived orally or in texts, songs, etc.

But the fact is that a whole series of apparatuses has been established ('popular literature', cheap books, but also what is taught in school) to block this development of popular memory, and you could say that the project has been, relatively speaking, very successful. The historical knowledge that the working class has about itself is becoming less all the time. When you think, for example, about what the workers knew about their own history at the end of the nineteenth century, and what the tradition of trade unionism - using the term 'tradition' in its full sense - represented up until the First World War, it amounted to something pretty substantial. That has been gradually disappearing. It's disappearing all the time, although it hasn't actually been lost.

Nowadays, cheap books are no longer enough. There are much more efficient channels in the form of television and cinema. And I think the whole effort has tended towards a recoding of popular memory which exists but has no way of formally expressing itself. People are shown not what they have been but what they must remember they have been.

Since memory is an important factor in struggle (indeed, it's within a kind of conscious dynamic of history that struggles develop), if you hold people's memory, you hold their dynamism. And you also hold their experience, their knowledge of previous struggles. You make sure that they no longer know what the Resistance was actually about ...

It's along some such lines, I think, that these films have to be understood. What they're saying, roughly, is that there has been no popular struggle in the twentieth century. This statement has been formulated twice, in two different ways. The first time immediately after the War , when the message was a simple one: 'The twentieth century, what a century of heroes! Churchill, de Gaulle, all those parachute landings, airborne missions, etc.' Which was a way of saying: 'There was no popular struggle, that was the true struggle: But no one, as yet, has said directly: 'There Was no popular struggle.'

The other, more recent way - sceptical or cynical, as you wish - consists in opting for statement pure and simple: 'Well, just look at what happened. Did you see any struggles? Can you see anyone rebelling, taking up arms?'

CAHIERS: There's a kind of rumour that's been going round since, perhaps, The Sarrow and the Pity. Namely: the people of France, in the main, didn't resist, they even accepted collaboration, they accepted the Germans, they swallowed the lot. The question is what that really means. And it does indeed seem that what is at stake is the popular struggle, or rather people's memory of it.

FOUCAULT: Exactly. That memory has to be seized, governed, controlled, told what to remember. And when you see these films, you learn what to remember: 'Don't believe everything you were once told. There are no heroes. And if there are no heroes, that's because there's no Struggle.' Hence a kind of ambiguity: on the one hand, 'there are no heroes' positively debunks a whole mythology of the war hero in the Burt Lancaster mould. It's a way of saying: 'War isn't that at al1!' Hence an initial impression that historical untruths are being stripped away: finally we're going to be told why we don't all have to identify with de Gaulle or the members of the Normandy-Niemen mission, etc. But hidden beneath the phrase 'There were no heroes' is another phrase which is the real message-'There was no struggle': That's how the process works.

CAHIERS: There's something else that explains why these films are successful. They make use of the resentment felt by those who did indeed struggle against those who did not. For example, in The Sorrow and the Pity people active in the Resistance see the citizens of a town in central France doing nothing, and recognize this response for what it is. It's their resentment that comes across more than anything; they forget that they struggled.

FOUCAULT: What's politically important, to my mind, more than this or that film, is the the fact that there's a series - the network that's made up of all these films and the place they 'occupy' (no pun intended). In other words, what is important is the question: 'Is it possible, at the present time, to make a film that's positive about the struggles of the Resistance?' And of course you realize that it isn't. The impression you have is that people would find it a bit of a joke, or else, quite simply, that no one would go and see it.

I quite like The Sorrow and the Pity. I don't think it was a bad thing to have done. Perhaps I'm wrong, that's not what matters. What matters is that this series of films corresponds exactly to the fact that it is now impossible - as each of the films emphasizes - to make a film about the positive struggles that may have taken place in France around the time of the War and the Resistance.

CAHIERS: Yes. It's the first thing they say if you criticize a film like Malle's. 'What would you have done instead?' is always the reply. And of course we don't have an answer. The left should be beginning to have a point of view on this, but in fact it has yet to be properly worked out.

Then again, this raises the old problem of how to produce a positive hero, a new type of hero.

FOUCAULT. The difficulties don't revolve around the hero so much as around the question of struggle. Can you make a film depicting a struggle without making the characters into heroes in the traditional sense? It's an old problem: how did history come to speak as it does and to recuperate the past, if not via a procedure which was that of the epic, that's to say, by telling its own story in the heroic mode? That's how the history of the French Revolution was written. The cinema proceeded in the same way. The strategy can always be ironically reversed: 'No, look, there are no heroes, we're all worthless, etc.'

CAHIERS: Let's come back to the 'retro style'. The bourgeoisie has been relatively successful from its own point of view in focusing attention on a historical period (the 1940s) which highlights both its strong and its weak points. For on the one hand that's where the bourgeoisie is most easily unmasked (it laid the ground for Nazism and collaboration), and on the other hand that's where today it tries to justify, in the most cynical way possible, its historical attitude. The problem is: how can we produce a positive account of this same historical period? We - that is, the generation that took part in the struggles of 1968 or Lip. Is this the point on which we should go in and fight, with the idea of possibly, in some way or another, taking the ideological lead? For it's true that the bourgeoisie is on the offensive as well as on the defensive on this question of its recenc history. On the defensive strategically, on the offensive tactically since it has found its strong point, the thing that enables it best co manipulate the facts. But ought we simply - defensively - co be re-establishing the historical truth? Ought we not to be finding the point which, ideologically, would take us into the breach? Is this automatically the Resistance? Why not 1789 or 1968?

FOUCAULT: As far as these films are concerned, I wonder whether something else couldn't be done on the same topic. And by 'topic' I don't mean showing struggles or showing that there were none. What I'm thinking is that its historically true that among ordinary French people there was, at the time of the War, a kind of refusal of war. Now where did that come from? From a whole series of episodes that no one talks about, neither the right because it wishes to hide them, nor the left because it does not want to compromise itself with anything that goes against 'national honour'.

During the First World War, after all, some seven or eight million lads were conscripted. For four years they had a terrible life, they saw millions and millions of people dying around them. Back home in 1920, what did they have to look forward co? A right-wing government, total economic exploitation and finally, in 1932, an economic crisis and unemployment. How could these men, who had been packed into the trenches, still be in favour of war during the decades 1920-30 and 1930-40? In the case of the Germans, defeat rekindled their nationalist instincts, so that this distaste for war was overcome by the desire for revenge. But when all is said and done, people don't like fighting bourgeois wars, with the officers involved, for the gains involved. I believe that was an important phenom_ enon in the working class. And when, in 1940, you have men driving their bikes into a ditch and saying, 'I'm going home', you can't just say, 'What a bunch of cowards' and you can't hide it either. It has co be seen as part of the whole sequence. This disobeying of national orders has to be traced back to its roots. And what happened during the Resistance is the opposite of what we are shown: that's to say that the process of repoliticization, remobilization, the taste for struggle was gradually revived in the working class. It slowly began to revive after the rise of Nazism and the Spanish Civil War. What the films show is the reverse process: after the great dream of 1939, which was shattered in 1940, people just give up. This process did indeed take place, but within another much longer process which was moving in the opposite direction and which, beginning with the distaste for war, ended in the middle of the Occupation with the realization that there had to be a struggle. As for the theme 'There are no heroes, everyone's a coward', you have to ask yourself where it comes from and what it grows out of. After all, have there ever been any films about mutiny?

CAHlERS: Yes. There was Kubrick's film (Paths of Glory), which was banned in France.

FOUCAULT: I believe that this disobedience in the context of national armed struggles had a positive political meaning. The historical theme of Lacombe Lucien's family could be picked up again if taken back to Ypres and Douaumont ...

CAHIERS: Which poses the problem of popular memory, of its own particular sense of time, which doesn't correspond at all to the timing of events like changes of government or declarations of war ...

FOUCAULT: The aim of school history has always been to show how people got killed and how very heroic they were. Look what they did to Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars ...

CAHIERS: A certain number of films , Malle's and Cavani's included, tend to abandon any attempt to deal with Nazism and fascism historically or in terms of the struggle they provoked. Instead of this, or as well as this, they hold another discourse, usually a sexual one. What do you make of this other discourse?

FOUCAULT: But isn't it quite different in Lacombe Lucien and The Night Porter? Personally, I think that in Lacombe Lucien the erotic, passionate aspect has a function that's fairly easy to pinpoint. It's basically a way of reconciling the anti-hero, of saying that he's not as anti-heroic as all that. If all power relationships are indeed distorted by him, and if he renders them ineffective, by contrast, just when you think that for him all erotic relationships are similarly warped, a true relationship is discovered and he loves the girl. On the one hand there is the machinery of power which leads Lucien more and more, from the puncture onwards, towards a kind of madness. And on the other hand there is the machinery of love which seems to be following the same pattern, which seems to be distorted and which, on the contrary, works in the opposite direction and re-establishes Lucien at the end as the beautiful naked boy living in the fields with a girl.

And so there's a kind of fairly facile antithesis between power and love. Whereas in The Night Porter the problem is - in general as in the present conjuncture - a very important one: it's that of the love of power.

Power has an erotic charge. And this brings us to a historical problem: how is it that Nazism, whose representatives were pitiful, pathetic, puritanical figures, Victorian spinsters with (at best) secret vices, how is it that it can have become, nowadays and everywhere, in France, in Germany, in the United States, in all pornographic literature the world over, the absolute reference of eroticism? A whole sleazy erotic imaginary is now placed under the sign of Nazism. Which basically poses a serious problem: how can power be desirable? No one finds power desirable any more. This kind of affective, erotic attachment, this desire one has for power, the power of a ruler, no longer exists. The monarchy and its rituals were made to evoke this kind of erotic relation to power. The great apparatuses of Stalin, and even of Hider, were also created for that purpose. But this has all disintegrated and it's clear that one cannot love Brezhnev or Pompidou or Nixon. It was perhaps possible, at a pinch, to love de Gaulle or Kennedy or Churchill. But what's happening now? Are we not seeing the beginnings of a re-eroticization of power, developed at one derisory, pathetic extreme by the sex shops with Nazi emblems that you find in the United States, and (in a much more tolerable but equally derisory version) in Giscard d'Estaing's attitude when he says, 'We'll march along the streets in suits shaking people's hands, and the kids will have a half-day holiday.' There's no doubt that Giscard fought part of his electoral campaign not just on his physical presence but also on a certain eroticization of his personal self, his elegance.

CAHIERS: That's how he projected himself in an election poster, the one where his daughter is facing him.

FOUCAUlT: That's right. He is looking at France but she is looking at him. Power becomes seductive once again.

CAHIERS: That's something that struck us during the election campaign, especially in the big television debate between Mitterrand and Giscard; they were on quite different territory. Mitterrand seemed like a politician of the old school, belonging to an old-fashioned left. He was trying to sell ideas, themselves dated and slightly quaint, and he did so with great dignity. Giscard on the other hand was selling the idea of power as if he were marketing a cheese.

FOUCAULT: Even quite recently, you had to apologize for being in power. Power had to be erased and not show itself as such. That was, up to a point, how democratic republics functioned: the problem was to render power sufficiently insidious and invisible so that it became impossible to get a hold on what it did or where it was.

Nowadays (and in this de Gaulle played a very important role), power is no longer hidden, it is proud to be there and actually says: 'Love me , because I am power.'

CAHIERS: Perhaps we should speak about the fact that Marxist discourse, as it has been functioning for some time, is somehow unable satisfactorily to account for fascism. Historically speaking, Marxism has accounted for the Nazi phenomenon in an economistic, determinist way, completely ignor ing what was specific to the ideology of Nazism. You can't help wondering how someone like Malle, well enough in touch with developments on the left, can play on this weakness, fall into this gap.

FOUCAULT: Marxism defined nazism and fascism as 'the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary fraction of the bourgeoisie'. This is a definition completely lacking in content, and one which lacks a whole series of articulations. What is missing in particular is the fact that Nazism and fascism were made possible only by the existence within the general population of a relatively large fraction willing to take on and be responsible for a certain number of state functions: repression, control, law and order. That, I think, is an important aspect of Nazism. The fact that it penetrated the general population so deeply and that some power was effectively delegated to certain people on the margins. That's where the word 'dictatorship' is both generally true and relatively false. When you think of the power an individual could possess under a Nazi regime from the moment he joined the SS or became a Party member! He could actually kill his neighbour, appropriate his wife and his house! That's where Lacombe Lucien is interesting, because it shows that side well. The fact is that, contrary to what one usually understands by dictatorship, that's to say the power of one individual, in a regime like that the most detestable, but in a sense the most intoxicating, part of power was given to a large number of people. It was the SS man who had the power to kill and to rape ...

CAHIERS: That's where orthodox Marxism breaks down. Because this implies that there has to be a discourse on desire.

FOUCAULT: On desire and on power ...

CAHIERS: That's also where films like Lacombe Lucien and The Night Porter are relatively 'strong'. They can handle a discourse on desire and power in a way that seems coherent.

FOUCAULT: In The Night Porter it's interesting to see how, in Nazism, the power of one man was taken up by many people and put to work. That sort of mock tribunal they set up is fascinating. Because from one angle it begins to look like a psychotherapy group, but in fact its power structure is that of a secret society. It's basically an SS cell that has re-formed, that gives itself legal powers different from and in opposition to the power at the centre. We have to remember how power was dispersed, how it was invested within the population itself, we have to remember this impressive displacement of power that Nazism brought about in a society like German society. It is untrue to say that Nazism was the power of the big industrialists continued in another form. It wasn't the power of the top brass reinforced. It was that too, but only on a certain level.

CAHIERS: Indeed, that's an interesting aspect of the film. But what seemed very questionable to us was that it seemed to be saying: 'If you're a typical SS man, that's how you behave. But if on top of that you have a certain "notion of expenditure", that's the formula for a great erotic adventure.' So the film never abandons the idea of seduction.

FOUCAULT: Yes, it's like Lacombe Lucien in that respect. For Nazism never gave anyone a pound of butter, it never gave anything but power. You have to ask yourself, if this regime was nothing other than a bloody dictatorship, how on 3 May 1945 there were still Germans fighting on to the last drop of blood, if these people were not attached to power in some way. Of course, you have to take into account all the pressures, denunciations ...

CAHIERS: But if there were denunciations and pressures, there must have been people to do the denouncing. How did people get caught up in it all? How were they ever conned by this redistribution of power in their favour?

FOUCAULT: In Lacomhe Lucien, as in The Night Porter, this excessive power that is given to them is converted back into love. It's very clear at the end of The Night Porter, with the recreation around Max, in his room, of a kind of concentration camp in miniature, where he is dying of hunger. There love has converted power, super-power, into total powerlessness. Roughly the same reconciliation occurs, in a sense, in Lacomhe Lucien, where love takes the excess of power by which it has been trapped and converts it inca a rural nakedness miles away from the Gestapo's shady hotel, miles away also from the farm where the pigs are being killed.

CAHIERS: Are we then perhaps beginning to explain the problem you were posing earlier: how is it that Nazism, which was a puritanical, repressive system, is now universally eroticized? Some kind of displacement takes place: a problem which is central and which people don't wish to confront, the problem of power, is bypassed or rather completely displaced towards the sexual. So that this eroticization is really a displacement, a form of repression ...

FOUCAULT: The problem is indeed a very difficult one and it has not perhaps been sufficiently studied, even by Reich. How is it that power is desirable and is actually desired? The procedures through which this eroticization is transmitted, reinforced, and so on, are clear enough. But for it to happen in the first place, the attachment co power, the acceptance of power by those over whom it is exercised, must already be erotic.

CAHIERS: What makes it all the more difficult is that the representation of power is rarely erotic. De Gaulle and Hitler weren't exactly attractive.

FOUCAULT: That's right, and I wonder whether in Marxist analyses one doesn't sacrifice a little too much to the abstract character of the idea of freedom. In a regime like the Nazi regime, it's quite clear that there's no freedom. But not having freedom doesn't mean that you don't have power.

CAHIERS: It's on the level of the cinema and television, television being entirely controlled by power, that historical discourse has the greatest impact. Which implies a political responsibility. It seems to us that people are increasingly aware of it. For some years now, in the cinema, there has been more and more talk of history, politics, struggle ...

FOUCAULT: There's a battle going on for history, around the history that's now in the making, and it is very interesting. People want to codify, to stifle What I have called 'popular memory', and also to propose, to impose a grid for interpreting the present. Until 1968 popular struggles had to do with folk tradition. For some they had no connection at all with anything going on in the present. After 1968 all popular struggles, whether in South America or in Africa, find an echo, a resonance. No longer can this separation, this sore of geographical cordon sanitaire, be established. Popular struggles have become not something that is happening now, but something that might always happen, in our system. And so they have to be set at a distance once again. How? Not by interpreting them directly - you would only lay yourself open to all the contradictions - but by proposing a historical interpretation of popular struggles from our own past, to show that in fact they never took place! Before 1968, it was: 'It won't happen, because it only happens elsewhere'; now it's: 'It won't happen, because it has never happened! Even something like the Resistance, the stuff of so many dreams, just look at it ... Nothing there. An empty shell, completely hollow!' Which is another way of saying: 'In Chile, don't worry, the peasants don't give a damn. In France too: a few troublemakers and their antics won't affect anything fundamental.'

CAHIERS: For us, the important thing when one reacts to that, against that, is to realize that it's not enough to re-establish the truth, to say, about the Maquis for example, 'No, I was there, it didn't happen like that at all!' We believe that to conduct the ideological struggle effectively on the kind of terrain that these films lead into you have to have a wider, more comprehensive system of references - of positive references. For many people, for example, that consists in reappropriating the 'history of France'. It was against this background that we spent some time on Moi, Pierre Riviere . .. because we realized that in the end, and paradoxically, it helped us to explain Lacombe Lucien, that the comparison brought out a number of things. For example, one significant difference is that Pierre Riviere is a man who writes, who commits a murder and who has a quite extraordinary memory. Malle's hero, on the other hand, is presented as a halfwit, as someone who goes through everything, history, the War, collaboration, without building on his experiences. And it's there that the theme of memory, of popular memory, can help us to make the distinction between someone, Pierre Riviere, who uses a language that is not his and is forced to kill to obtain the right to do so, and the character created by Malle and Modiano 8 who proves, precisely by not building on anything that happens to him, that there is nothing worth remembering. It's a pity you haven't seen The Courage of the People. It's a Bolivian film, which was made for the speClfic purpose of providing an exhibit for a dossier. This film, which can be seen everywhere except in Bolivia, because of the regime, is played by those who actually took part in the real-life drama it recreates (a miners' strike and its bloody repression) - they undertake to represent themselves so that no one will forget.

It's interesting to see that, on a minimum level, every film is a potential archive and that, in the context of a struggle, one can take this idea one step further: people put together a film intending it to be an exhibit. And you can analyse that in two radically different ways: either the film is about power or it represents the victims of that power, the exploited classes who, without the help of the cinematographic apparatus, with very little knowledge of how films are made and distributed, take on their own representation, give evidence for history. Rather as Pierre Riviere gave evidence, that's to say, began to write, knowing that sooner or later he would appear before a court and that everyone had to understand what he had to say.

What's important in The Courage of the People is that the demand actually came from the people. It was through a survey that the director first learned of the demand, and it was those who had lived through the event who asked for it to be memorized.

FOUCAULT: The people create their own archives.

CAHIERS: The difference between Pierre Riviere and Lacombe Lucien is that Pierre Riviere does everything to enable us to discuss his history after his death. Whereas, even if Lacombe is a real character or one who might have existed, he is only ever the object of another's discourse. for purposes that are not his own.

There are two things that are successful in the cinema now. On the one hand, historical documents, which have an important role to play. In Toute une vie, for example, they are very important. Or in films by Marcel Ophuls or Harris and Sedouy, when you see Duclos waving his arms about in 1936 and in 1939, these scenes from real life are moving. And on the other hand, fictional characters who, at a given moment in history, compress social relations, historical relations, into the smallest possible space. That's why Lacombe Lucien works so well. Lacombe is a Frenchman under the Occupation, someone very ordinary who stands in a concrete relationship to Nazism, to the countryside, to local government, etc. We have to be aware of this way of personifying history, of bringing it to life in a character, or a group of characters who, at a given moment, stand in a privileged relationship to power.

There are lots of characters in the history of the workers' movement whom we don't know about: lots of heroes in the history of the working class who have been totally repressed. And I believe that something important is at stake here. Marxism doesn't need to make any more films about Lenin, there are more than enough already.

FOUCAULT: What you are saying is important. It's a characteristic of many Marxists today. They don't know very much about history. They spend their time saying that history is being overlooked, but are only capable themselves of commenting on texts: 'What did Marx say? Did Marx really say that?' But that is Marxism if not another way of analysing history itself? In my opinion, the left, France, is not very interested in history. It used to be. In the nineteenth century you could say that Michelet represented the left at a given moment. There was also Jaures, and then a kind of tradition of left-wing, social democratic historians (Mathiez etc.). Today that has virtually dried up. Whereas it could be an impressi"e movement of writers and film-makers. There was of course Aragon and Les Cloches de Bale, which is a very great historical novel. But it doesn't amount to much, if you think of what that could represent in a society whose intellectuals are, after all, more or less steeped in Marxism.

CAHIERS: Film-making brings in something new again in this respect: 'live' history ... What relation do American people have to history, now that they see the Vietnam War every evening on television as they eat their supper?

FOUCAULT: As soon as you begin to see images of war every evening, war becomes utterly accepted. In other words, extremely boring - you would certainly prefer to watch something else. But once it becomes boring, it's accepted. You don't even watch it. So what do you have to do for this news, as it appears on film, to be reactivated as news that is historically important?

CAHIERS: Have you seen Les Camisards?

FOUCAULT: Yes, I liked it a lot. Historically it's beyond reproach. It's a beautiful film, it's intelligent, it explains so much.

CAHIERS: I think that's the direction film-makers should be taking. To come back to the films we were talking about at the beginning, another problem that must be mentioned is the confused response of the far left to certain aspects of Lacombe Lucien and The Night Porter, the sexual aspect especially. How might the right take advantage of this confusion?

FOUCAULT: On this subject of what you call the far left, I don't really know what to think. I'm not even sure whether it still exists. All the same, a huge balance sheet has to be drawn up for the activities of the far left since 1968: the conclusions are negative on the one side and positive on the other. It's true that the far left has been responsible for a whole lot of important ideas in a number of areas: sexuality, women, homosexuality, psychiatry, housing, medicine. It has also been responsible for the diffusion of modes of action-which continues to be important. The far left has been important in the kinds of action it has taken as well as in the themes it has pursued. But there is also a negative balance in terms of certain Stalinist, terrorist, organizational practices. And there is equally a misapprehension of certain currents running wide and deep which have just resulted in thirteen million votes for Mitterrand, and which have always been neglected on the pretext that that was just politicking, party politics. Any number of aspects have been neglected, notably the fact that the desire to defeat the right has for some years, some months, been a very important political factor among the masses. The far left didn't have this desire because its definition of the masses was wrong and because it didn't really understand what it means to want to win. To avoid the risk of having victory snatched away it prefers not to run the risk of winning. Defeat, at least, can't be recuperated. Personally, I'm not so sure.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Interesting that Asterix the Gaul, comic strip about plucky native resistance to Roman imperialism, started the very year that Charles de Gaulle, hero of the Resistance, launches the Fifth Republic...

Mind you, other people have diagnosed it as being an allegory of American cultural imperialism, or even the Algerian war of independence...

One intriguing counterfactual in rock history is what would have happened if drummer Kenny Morris and guitarist John McKay had not quit Siouxsie and the Banshees at the start of a major tour - after an altercation at an LP signing session in an Aberdeen record shop...

McKay & Morris broke their silence about their seemingly impulsive decision to leave a few months later, in December '79

In the counterfactual scenario, Morris & McKay stick around - and Budgie and John McGeoch do not join as their replacements...

And while you wouldn't want to have missed all the amazing music that the new line-up created - "Happy House", "Christine", all of Juju, all of A Kiss in the Dreamhouse, "Fireworks" etc - I wouldn't have minded an album or two more in the Scream / Join Hands mode.

The difference is like the switch between monochrome and Technicolor.

In "Concrete Pop", a 1986 piece written for Monitor, Chris Scott - who vastly preferred the first-phase Banshees - argued for the higher powers of the non-virtuoso and the untrained:

"Now: the archetypal goth band, drone drone drone, texture texture texture, the sound of the sea. Then: the sound of people doing things to objects. Being a punk Siouxsie treated even her voice as an object, and more spectacularly than Rotten or Poly Styrene. The music was not just an atmosphere: it kept us aware of the presence of the instrument, the object and of the presence of the people manipulating the objects, communicating with us because we were kept aware that someone had made these noises for us. Each sound itself was like an object put there for our consideration. Buying that first LP was like finding a huge rusting metal thing in the street, bringing it home and putting it in the middle of your bedroom just because it looked so good. Buying a Banshees album today is like buying a settee. Or a carpet."

He also made an invidious contrast between the two drummers: Kenny Morris's "epochal battering" versus Budgie getting "his drumsticks specially made 200 at a time - rockstars are dead, eh""

When I interviewed Steve Severin he made some points compatible with the Chris Scott viewpoint:

"When you listen to The Scream, you can hear the fingers on the strings, the effort that's actually going into it. You get to the end of a track and you can hear Kenny breathing."

The sound-style emerged out of the combo of the performer's limitations and their active aversions. Severin again:

"It was a case of us knowing what we didn't want, throwing out every cliché. Never having a guitar solo, never ending a song with a loud drum smash. At one point, Siouxsie just took away the hi-hat from Kenny Morris's drum kit."

Here's a bit on Morris's approach to drumming from an interview done only a few years ago by Ellie O'Byrne:

His unorthodox, self-taught drumming style used almost no cymbals: he would turn his sticks round the better to belt his drum kit as hard as he possibly could. Siouxsie said he was like a marionette seated at his kit.

"I was really physical on the drums," he says. "When I eventually got my own kit, it had to be practically specially built. I think it was '78 before I even got that."

"I had a Pearl Drum Kit with a special indestructible pedal. When most drummers use a ride cymbal, I didn't want a ride. I'd have my high hat and a crash and an upside down Chinese cymbal. I would play time on the side drum, not the ride. When I got a riser, I made chalk marks where they had to drill holes and attach metal clasps to secure the cymbal stands."

Still, as severe as the first-phase Banshees could be, the single were pop punchy.

Things like this flange-ferocious beauty - a medium-size hit single

The earlier Banshees also had a better, more coherent look as a band - McKay's beauty, Kenny Morris's pallor, contributed as much as Siouxsie and Severin.

High-contrast black-and-white - the look mirrors the sound of The Scream and Join Hands.

One wonders if the first-phase was selected as much for appearance as ability (since none of them had it or sought it, then).

Whereas the second-phase new recruits were picked for their musical accomplishment and the way that would enable the Banshees to expand and evolve.

I pose that counterfactual query about John and Kenny not leaving at the end of this review of a Deluxe Reissue of The Scream

Siouxsie and the Banshees

The Scream

Uncut, 2005

Knowing Siouxsie as Godmother of Goth, it's easy to forget that the Banshees were originally regarded as exemplary postpunk vanguardists. Laceratingly angular, The Scream reminds you what an inclement listen the group was at the start. Sure, there's a couple of Scream tunes as catchy as "Hong Kong Garden" (which appears twice here on the alternate-versions-crammed second disc of BBC session and demos). "Mirage" is a cousin to "Public Image," while the buzzsaw chord-drive of "Nicotine Stain" faintly resembles The Undertones, of all people.

But one's first and lasting impression of Scream is shaped by the album's being book-ended by its least conventional tunes. Glinting and fractured, the opener "Pure" is an "instrumental" in the sense that Siouxsie's voice is just an abstract, sculpted texture swooping across the stereo-field. Switching between serrated starkness and sax-laced grandeur, the final track "Switch" is closer to a song but as structurally unorthodox as Roxy Music's "If There Is Something".

Glam's an obvious reference point for the Banshees, but The Scream also draws from the moment when psychedelia turned dark: "Helter Skelter" is covered (surely as much for the Manson connection as for Beatles-love), guitarist John McKay's flange resembles a Cold Wave update of 1967-style phasing, and the stringent stridency of Siouxsie's singing channels Grace Slick. In songs like the autism-inspired "Jigsaw Feeling," there's even a vibe of mental disintegration that recalls bad trippy Jefferson Airplane tunes like "Two Heads."

Another crack-up song, "Suburban Relapse" always makes me think of that middle-aged housewife in every neighbourhood with badly applied make-up and a scary lost look in her eyes. Siouxsie's suspicion not just of domesticity but of that other female cage, the body, comes through in the fear-of-flesh anthem "Metal Postcard," whose exaltation of the inorganic and indestructible ("metal is tough, metal will sheen… metal will rule in my master-scheme") seems at odds with the song's inspiration, the anti-fascist collage artist John Heartfield.

Scream is another Banshees altogether from the lush seductions of Kaleidoscope and Dreamhouse. McKay and drummer Kenny Morris infamously quit the group on the eve of the band's first headlining tour, and their replacements--John McGeoch and Budgie--were far more musically proficient. Yet The Scream, along with early singles such as 'Staircase Mystery" and the best bits of Join Hands, does momentarily make you wonder about the alternate-universe path the original Banshees might have pursued if they'd stayed together and stayed monochrome 'n' minimal.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

From the O'Byrne interview, Morris's account of the breakup at the Aberdeen record shop LP signing session:

"When we left the record shop, we went outside and went, 'what are we going to do?' So we went back to the hotel. Margaret Thatcher was staying there too, so security was everywhere: guys talking into their sleeves."

They booked a taxi but, fearful of the rest of the band catching up with them, lied to the receptionist and said they were going to the train station when in fact they were headed to the airport.

The band did arrive, just as they were leaving.

"[Banshees manager] Nils came up to the taxi and reached in through the window, and started trying to strangle me," Kenny says. "So I wound the window up on his arm. He fell to the floor and he was going, 'I'll see you never work again. I've invested 45,000 in this tour!' and John was going, 'have you? Whose money? Is that our money, Polydor's money?' Things had gotten that bad that we didn't know."

A film made by Kenny Morris, said to be an allegorical account of the break-up

Kenny Morris interviewed by John Robb, who - nothing if not direct and to the point - immediately, bluntly, asks him, "so, what have you been doing for the last 30 years?"

Ooh, a weird loop - in Chris Scott's "Concrete Pop" article, Robb's group the Membranes are considered exemplars (as was The Rox, Robb's zine, in Chris's earlier Monitor article celebrating fanzines for their aesthetic of anti-professionalism).

Of course, I'm a big fan of atmosphere, "the sound of the sea". A nice-looking settee, an attractive carpet - what's the problem?

I also like a nicely laid out page.

Here is Matt's lovely tribute to the Black Dog from a few years ago

Here's my own writing about the group:

THE BLACK DOG, The Book of Dogma