I remember when there were no "Black Friday Sales Events," 'cuz I done be olde, chile. I think I first saw a Black Friday commercial this year pre-Halloween. Is nothing sacred?

Our hearts bleed for all the subsidiaries of Omnicorp, their middle managers' jobs on the line unless they come fiscally through before the next earnings report. If the increasingly poor masses don't show up for Holiday Savings, you can just see Virgil from Sales eyeing your job. Did you sign up for this? Yes, you did.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

(When I'ze a kid we were so poor we couldn't afford snow, much less a snowman. And besides, it was 80 degrees in Los Angeles.)

When Black Fridays started up and became a Thing I remembered how Big Biz can make up shit and it flies. Advertising is magic! They taught me that in Brainwashing 101. Repetition repetition repetition repetition sex repetition repetition status class anxiety repetition repetition fear repetition. Need I say more?

Then everyone got an email address and a personal computer and voila!: "Cyber Monday" and its supposedly marvelous savings on all things enshittified. Do you really need a second salad spinner? No, you don't, so salt away that dough for your next weed purchase. Be a Smart Shopper. Word to the wiseguys.

The once-fairly-robust charitable (write-offs) groups weighed in with "Giving Tuesday." Somehow, that also seemed to fly, though we wonder for how long. If I had any money left after Black Friday "sales events" and, following closely on the heels of Black Friday, Insolvency Saturday and Scheming Sunday, I'd love to subscribe to someone else's Substack on Giving Tuesday. Lawd knows y'all need it. Hell: I need it, hence my self-serving bit here. But as my Brit friends say, I'm skint from Black Friday and Cyber Monday. I ain't got dime nor shekel for Giving Tuesday. I lack drachmas, even. I'm bereft of lire, no oodles of rubles. I yearn for yen. For some serious Euros. A cold wad of cash that could choke Secretariat. Need me to paint a picture fer yas?

But nonetheless let's all keep our chins up in the face of all the forced revelry. They harvested Jesus at this time of year or some shit, and Santa, who began as a psychedelic mushroom god from Norway, wants to bring us stuff. I'm still kinda hazy on the origins, so cut me some slack: it's Christmas! 'Tis the season, brothers 'n sistuhs. Damn straight!

I kid about Black Friday: I didn't buy a damned thing. Out of solidarity. Also: I am Bonneville Salt Flat-broke. So there's that.

HEY LQQK!: Here's a Scheme!: Next year let's all try to gin up support for the day after Black Friday: Substack Subscription Saturday, in which those who still have savings and paying jobs are heavily pressured and guilt-tripped into supporting us. We get in after Black Friday and before Cyber Monday, when the xmas spirit is still not showing gooey black flecks around the edges. Blow me, Cyber Monday! Sorry, Giving Tuesday, but we were in line first. The line starts way back there.

Maybe a non-profit will make a short commercial for us that we can get on…TV? YouTube? A huge billboard outside Ebbing, Missouri? Anyway, we need exposure to the Monied Reading Class, which is a thing, or this bit doesn't work. We need some annoying, riveting, garish ad in which we're all sitting around in the hot dirt with old Smith-Coronas, our hair tousled, conspicuous Band-Aids on our exposed flesh, and flies (use honey!) dive-bombing our heads, with the voice-over of a Charlie Brown sounding Kute Kid saying, "Won't you…help out a hungry writer today?" (hat-tip: Sally Struthers)

Who's with me?

After you've spend too much from your dwindling holiday budget, it's on to Woeful Wednesday, followed by Taciturn Thursday, when no one feels like talking to anyone else because let's face it the System and blah blah blahgetty-blah-OOF! a-heynonny nah nah goodbye. You and your wallet are depressed. And you don't wanna talk about it, so shut the fuck up. (Breathe…count seven, exhale, count seven…: repeat until you feel relaxed, and good and jaded. But relaxed and jaded.)

Fed-Up Fridays are now all the rage, and I mean that literally. You don't want to cut off anyone in traffic that day, a cold early December one, especially in the Northeast or my hometown, insane Los Angeles and its environs. Southside Chicago has been simmering since Woeful Wednesday, which they call Watch Your Back Wednesday, and they joke that Fed Up Friday is Fucked Up Friday, in which half the working population calls in sick to get drunk. Vengeance for harms done by faceless corporations and their stooges in Congress fires the hearts of men and women (could it be indigestion?), and even some children then. Much plotting is feverishly concocted in cold "low cost" housing, but then they realize they lack revolutionary fervor 'cuz they too damned drunk. Even some of dem kids. Hey, I feel ya. I really do. (I mean all this figuratively, fer crissakes.)

Slingshot Saturdays have been gaining every year for the last decade now: when you're out of money for the holidays, you might be sued for what you did on Fed-Up Friday, and you can't wait for It all to blow over soon and you're thinking you might get into Buddhism. On this day we all would like to think we could slay the Giant, but…courage. I tend to be more the Dennis the Menace type on Slingshot Sunday, picking off the Haves, or at least pestering them with a handy dirt clod or tiny bits of gravel. I once knocked a clip-on tie off a haughty bourgeois Republican coming out of church from 35 feet. I was pursued on foot until I hopped a fence like I was that Matt Damon character in that action series of films I've never seen.1 They gave up and I had a hearty laugh, until I noticed a nasty gash on my tibia.

Use camouflage and take cover behind a Help Wanted sign and they'll never see ya. Pro tip…

The following day, Sour-Sarcastic Sunday ("Thanksgiving was ten days ago," you recall, counting on your fingers, because you're still reelin' from the new medication you started taking, the one Charlie the Dealer sold you in the park), always reveals the general tenor and mood of the People as the days of Xmas Cheer get louder and more ominous.

Let me take a moment here to wish everyone a Hot Hanukkah and a Krazy-Assed Kwanzaa. Don't take shit from anybody, you guys! Light the hell outta them candles and a hearty Karamu, too. Please cook everything thoroughly, because the now-compromised FDA ain't checkin for salmonella at all anymore, it seems.

Just an observation. How's your week goin'? Tell me your favorite Slingshot Saturday anecdote in the comments!

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1It's right on the tip of my tongue. Jason something. Voorhees? The Voorhees Ultimatum? Gimme time. I decided to watch the entire history of film and I'm only up to 1913 right now.

(artwork by B. Campbell)

What is the OG on about now? It's just common sense to think about common sense. Or is it?

[tl;dr1: Using the term "common sense" is just me bullshitting myself and others; the plain (delightful) fact is we're just gonna have to cultivate our thinking more.]

Three reasons impelled me to address this idea:

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The seemingly sudden and swift decline of the unique self, the weirdo personality honestly derived, the desire to speak one's mind without regard to Herd Hearsay and "I Done Seen It Onna Internet"-mind.

That this decline has been driven by algorithms and dopamine-addiction to screens, and the increasingly common fear that one's individuality is seeping away, kinda like the Cheshire Cat's body, but being glued to screens all day will eat that smile up too. I think the popularity of Severance and the newer show Pluribus (which I have not seen but have read quite a lot about), and my reading of a thousand testimonies in disparate places about the personal jihad of trying to wrest a human life away from Tik-TokFacebookXitterBlueskyInstagramLinkedIn, etc. also inform this query. Are our "selves" imperiled as of 2006, or 2014, or whenever everyone was suddenly obsessed with being "liked" by distant strangers?

This question should be wide-open to everyone. If you notice all your friends are agreeing about what "common sense" is (it's highly likely it's what you and your friends think it is), the only game-rule would be: name those who don't seem to agree with you and at least one of you pretend you're one of them, acting as an advocate for the people who disagree with you. In other words, temporarily pretend you're one of Them. This should involve some acting and will be good for major laffs. Follow this up by having a good faith back 'n forth about why those who don't have "common sense" maybe think like they do, in that weird wrong way that's not like the way you think. If you do this with aforementioned good faith while entertaining a little bit of your famous "open-mindedness" there's a chance it will put you in a slight altered state of consciousness.

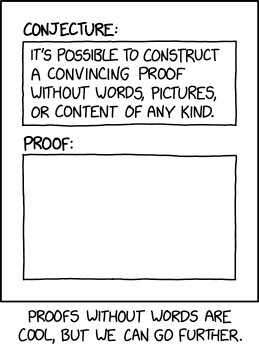

So: what "is" common sense? As of the date I'm writing this, I see it as a species of bullshit rhetoric that's appealing to people who don't want to think: what we already think about X,Q,Z, and R is just "common sense." No more need to think about it. In this, it seems a kissin' cousin to "human nature." It bears a family resemblance to Naive Realism. Those Americans who still think little things like seceding from Britain and getting ourselves a Constitution ratified was a good idea will give Thomas Paine's agitprop a bye for this round.

Some history and examples and Just Plain Fun ensues:

Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), arguably the father of the modern social sciences, wrote this line in his New Science: "Common sense is an unreflecting judgement shared by an entire social order, people, nation, or even all humankind."2

Bertrand Russell had a line on this (because of course he did): "Common sense, do what it will, cannot avoid being surprised occasionally. The object of science is to spare it this emotion and create mental habits which shall be in such close accord with the habits of the world that nothing shall be unexpected."3

Alfred Korzybski, in his 1921 book Manhood of Humanity seems to think that "common sense" is a very difficult problem - a Hard Problem - and he thinks an understanding of our deep history must play a big part in decoding what this strange beast "common sense" might consist of:

Such I take to be the counsel of wisdom - the simple wisdom of sober common sense. To ascertain the salient facts of our immense human past and then to explain them in terms of their causes and conditions is not an easy task. It is an exceedingly difficult one, requiring the labor of many men, of many generations; but it must be performed; for it is only in proportion as we learn to know the great facts of our human past and their causes that we are enabled to understand our human present, for the present is the child of the past; and it is only in proportion as we thus learn to understand the present that we can face the future with confidence and competence. Past, Present, Future - these can not be understood singly and separately - they are welded together indissolubly as one.4

In this "sober common sense" I don't see anything "simple;" rather: the neo-Darwinian paradigm was just getting off the ground. He published this book in 1921, and in 1925 schoolteacher John T. Scopes was put on trial for teaching Evolution. I'm betting that somewhere in the transcript William Jennings Bryan argued that we could not have descended from apes was just "common sense."

A funny thing happened along the way from Korzybski's desiderata to our present time: History got vastly complex and entangled. Just hang with academic Amy J. Elias here when she's explicating Linda Hutcheons's poetics of postmodernism and history, as found in an essay about Thomas Pynchon's uses of history:

{…] postmodern fiction questions the assumption that the writing of history is transparent and neutral by asserting that all values are context dependent and ideologically inflected, contests notions of history's teleological closure and developmental continuity, and tries to demonstrate that all historical accounts are emplotted in the manner of fiction rather than merely recorded in the manner of science.5

Lest we assume the long hard slog of encircling some sort of philosophical anthropology derived from something like Neuroscience and Evolutionary Psychology…this uhhhh…seems like too tall an order to find out what "common sense" could really mean…and hey: maybe let's get hard-headed and think like a Mathematician in order to close in on our prey. But then, in 1931, the same year as Gödels' Incompleteness Theorem:

One of the chief services which mathematics has rendered the human race in the past century is to put "common sense" where it belongs, on the topmost shelf next to the dusty canister labeled "discarded nonsense."6

George Lakoff the cognitive scientist wrote this about the claim of "common sense":

One of the things most studied in cognitive science is common sense. Common sense cannot be taken for granted as a given. Whenever a cognitive scientist hears the words, "It's just common sense," his ears perk up and he knows there's something to be studied in detail and depth - something that needs to be understood. Nothing is "just" common sense. Common sense has a conceptual structure that is usually unconscious. That's what makes it "common sense." It is the commonsensical quality of political discourse that makes it imperative that we study it.7

I don't know about you, but by now my head is spinning and I feel like whatever common sense I had before I started writing this spew has long circled the drain and is headed straight for the Pacific Ocean. I muddle onwards!..

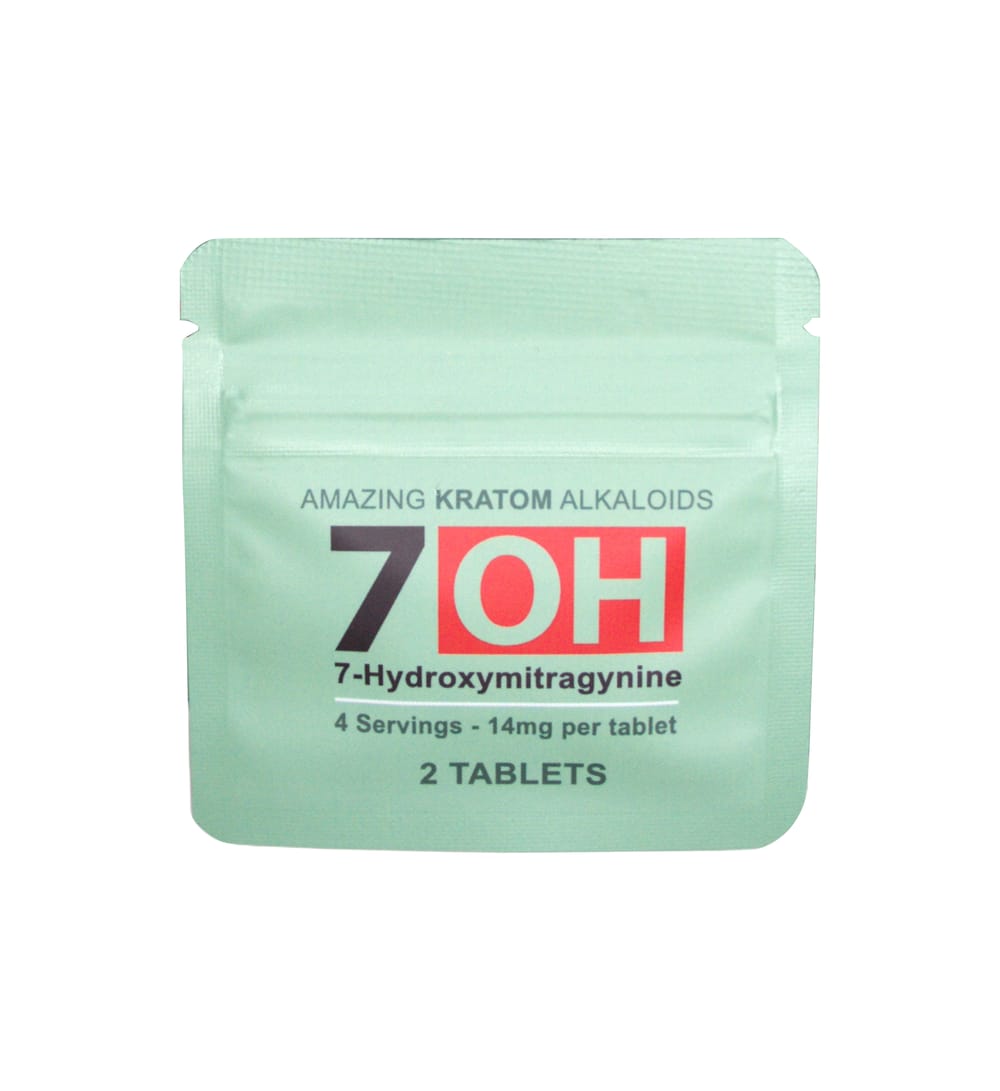

The phenomenological sociologists I've studied might call this "unconscious" aspect of common sense a variation on the "seen but not noted" world. It's the invisible or not-noted stuff that seems ultra-powerful, mostly for being not noted. Or that it's unseen. Unquestioned. I love anything like this because it takes me out of myself while I'm studying it, kinda like a mild psychedelic drug trip. Here, I'm tellin' ya who I "am," in case ya didn't know. Let's face it, to be interested in such things is just common sense.8

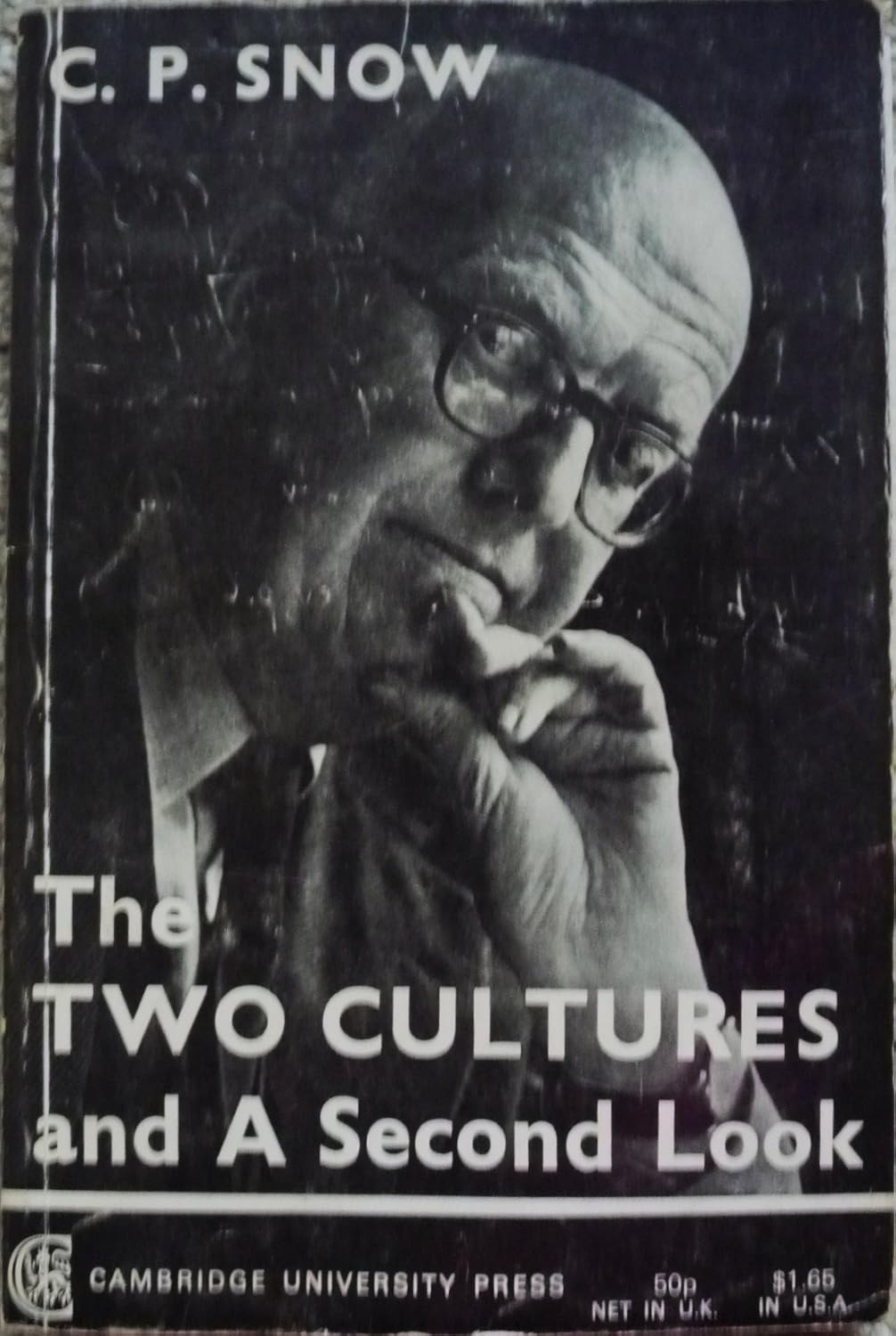

The worldly-universalist reader might immediately jump to knowledge of the social worlds of non-Anglo peoples found throughout the world and how their "common sense" seems wildly different than any of ours, as recorded by embedded cultural anthropologists since at least the early roarin' 20th century. In E. Doyle McCarthy's Knowledge As Culture: The New Sociology of Knowledge, there's a fine discussion about the origins of the term "ideology" and by Napoleon's time it seemed to be a battle between the eggheads and the owning class of the rich and their politicians:

Such a description brings to mind C. Wright Mills's "men of affairs," those sober citizens who parade themselves as hard-headed realists, epitomizing what Richard Hartland calls the Anglo-Saxon variety of common sense: "Anglo-Saxons have the feeling of having their feet very firmly planted when they plant them upon the seemingly solid ground of individual tastes and opinions, or upon the seemingly hard facts of material nature." Accordingly, ideologists do not base their ideas on experience, but resort instead to ideas and deceits - to ideologies.9

One of my great intellectual loves, Robert Anton Wilson, loved to riff on "common sense" throughout his writing career, c.1959-2007. Here's a line from an article he wrote in New Libertarian, c.1977: "Common sense" is…

[…] the body of hominid (or primate) prejudice that is so widespread that only philosophers, mathematicians, physicists, and other eccentrics ever contradict it.10

In a discussion about the flux of individual perception and experts and authorities refereeing over what thoughts and apparent sense perceptions and observations/abstractions are allowable and which reports must be damned, Wilson wrote:

The world is forever spawning Damned Things - things that are neither tree nor shrub, fish nor fowl, black nor white - and the categorical thinker can only regard the spiky and buzzing world of sensory fact as a profound insult to his card-index system of classifications. Worst of all are the facts which violate "common sense," that dreary bog of Stone Age prejudice and muddy inertia.11

Perhaps better (or worse, depending on how much you think we can nail down this gnome "common sense"), RAW, in a long excursion on various epistemologies in the foxy 20th century, cites P.W. Bridgman, also a fave of Korzybski:

Operationalism, created by Nobel physicist Percy W. Bridgman, attempts to deal with the "common sense" objections to Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, and owes a great deal to pragmatism and instrumentalism. Bridgman explicitly pointed out that "common sense" derives unknowingly from some tenets of ancient philosophy and speculation - particularly Platonic Idealism and Aristotelian "essentialism" - and that this philosophy assumes many axioms that now appear untrue or unprovable. Common sense, for instance, assumes that the statement, "The job was finished in five hours" can contain both absolute truth and objectivity. Operationalism, however, following Einstein (and pragmatism) insists that the only meaningful statement about that measurement would read, "When I shared the same inertial system as the workers, my watch indicated an interval of five hours from start to finish of the job."12

Because you haven't heard enough from RAW here: "You are walking down the street, and you see an old friend approaching. You are astonished and delighted, because you thought he had moved to another city. Then the figure comes closer and you realize your perception-gamble (as transactionalists call it) had been in error: the person, as he passes, is clearly registered as a stranger. This does not alarm you, because it happens to everybody, and daily 'common sense,' without using the technical terms of quantum physics and transactional psychology, recognizes that perception and inference are probabilistic transactions between brain and incoming signals."13

Now I gotta get outta here 'cuz Lulu is ringin' the dinner bell, so I'll add to this flummery by citing a living philosopher, Eric Schwitzgebel, who was at UC Riverside last I saw. Prof. Schwitzgebel argues that all famous philosophers, when arguing about metaphysics, all sound "crazy" at some point. Why? 'Cuz "there's no way to develop an ambitious, broad-ranging, self-consistent metaphysical system without doing serious violence to common sense somewhere. It's just impossible." But: "common sense", Schwitzgebel asserts, is an "acceptable guide to everyday practical interactions in the world. But there's no reason to think it would be a good guide to the fundamental structure of the universe." To bolster this last thought he cites Relativity and Quantum Mechanics.14

And here I stand, with Schwitzgebel, not in the same inertial frame as me right at the moment, but close enough, the Professor is.

Thought Experiment results: I have no idea what the fuck I'm talking about when I mention "common sense."

(Site logo artwork done by Bobby Campbell)

1I realize my articles are usually longer than what most writers do here, but if "tl;dr" why are we reading my Substack, anyway? Move on to the next person's thing! There's a lot of shorter good stuff out there. I don't wanna be a bring-down.

2New Science, Vico, trans. by Dave Marsh, Penguin ed, section #142. Vico's "unreflecting" is one of my favorite takes on this topic of "common sense." Nota bene the ballsy gall of Vico to claim this for an entire people! No wonder James Joyce loved Vico so much. Later, the Frankfurt School tended to see similarly that common sense was for common thinkers, and one of them called common sense "the spontaneous ideology of everyday life." - see The Dialectical Imagination, Martin Jay, p.60.

3found in Science and Sanity, Korzybski, 4th ed, p.491. This outlook on what science ought to be able to do for us was shared by Korzybski, and feels like "scientism" now. We need to get to the point where nothing is unexpected (fat chance, Bertie, I say to you in 2025!), and that poor ol' "common sense" is no longer surprised or caught off guard. But we know now we will always be caught off guard with astonishment, Lord Russell. It shall not cease! The utopian ideals for critical thinking and rational technological utopianism by so many great thinkers in the first half of the rollicking 20th century feels like 500 years ago, and not merely 100, at least to me. The scientific millenarianism of folks like Russell and Korzybski - that we're in for a future of justice, peace, prosperity and end of hunger, war, and ignorance, possibly the end of death - is a world long lost, but then again a lot of these dudes were feelin' it then. Some sort of Golden Age will return, etc. Korzybski knew of the social powers of science and mathematical thought but also warned, as I mention in the next footnote, that we gotta get our act together as homo sap or we're cooked. Hack language thoroughly: this we must do in order to get to some sorta Engineer's Dream Garden. It seemed like common sense to them. At the time. Wittgenstein thought common sense was "nothing more than a web of linguistic practices common to a certain community." Or at least that's Richard Rorty's reading of Wittgenstein. See Take Care of Freedom and the Truth Will Take Care of Itself, p.78. Rorty himself thought common sense was part of the workings of philosophers who took pleasure in linking new, weird ideas with old ones, an idea that of course I would favor too.

4Manhood of Humanity, Korzybski, pp. 171-172. He wrote this book in the wake of the Great War, having been in it, and injured. A Polish Count who spoke five languages, his main thesis at this point was that humanity needs to grow the fuck up ASAP. We did not. He saw the 1939-1945 war and kept working to help humans understand how language can lead us astray, and very many ways to hack language so you don't keep acting like a damned ape. Among those writers who were influenced by him: Neil Postman, Robert Anton Wilson, Robert Heinlein, Alan Watts, Fritjof Capra, William S. Burroughs and many others. That the physical sciences were just beginning their cultural ascendance in the West need not be remarked upon, but by the early 21st century, polymathic scientist Jared Diamond argued that too many brilliant scientists had gotten too caught up in the details of some "fanciful" hypothesis that they really should think with more "common sense." See This Idea Is Brilliant, (2018), ed. John Brockman, pp.221-224.

5Cambridge Companion to Thomas Pynchon, pp.124-125. When you actually get into a grokduel with others over "common sense" it might be a good idea to rehearse some of these phrases to pull out and use to throw your interlocutors off their game, and win points:

Your pal: So I say common sense is a mere historical contingency as used by diverse groups in a class struggle.

You: Yes, yes, but the notion of teleological closure implied within any argument for common sense contains a suspect developmental continuity and conceals, like, ya know? how history is written more like fiction, with emplottments and…

Another pal; Where are you getting this shit? Pass the bong over here, please.

Weird roommate: Yea dude, you're being ideologically inflected bigger 'n shit. Anyone seen my Marley CD?

6Mathematics: Queen of the Sciences, Eric Temple Bell. (1931). I found this quote in Robert Anton Wilson's novel The Universe Next Door, p.68, original paperback ed. Bell was a student of Cassius Keyser, who was a close friend of Korzybski. Bell's work influenced John Nash and the prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, Andrew Wiles. It seems highly likely that "The map is not the territory", usually attributed to Korzybski, was derived from Bell. When Bell taught at CalTech, Korzybski lived nearby and they traveled in some of the same circles.

7Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know That Liberals Don't, G. Lakoff, p.4. My copy is an early version of the book, and the subtitle was changed to How Liberals and Conservatives Think, possibly because the earlier version might lead you to think this was another Frank Luntz-type book? Psychonaut-intellectual Dale Pendell asked his mentor Norman O. Brown about common sense and NOB replied, "Common sense never interested me." See Walking With Nobby, p.151 The context was a conversation in which William James comes up and Pendell says James has a certain common sense, then NOB says William James didn't turn him on, then the above line about common sense, then NOB says this was a Freud problem: Freud and his crew tried to make psychoanalysis common sense and to NOB that was a mistake. Lakoff's bete noir (or one of 'em: Chomsky's way up there), Steven Pinker, asserted that common sense is not in operation when a decision must be made between two competitors whose interests are partly shared. See How The Mind Works, p.409

8No, it ain't.

9Knowledge As Culture: The New Sociology of Knowledge, McCarthy, p.32 (Routledge, 1996) My favorite model of ideology is from Mannheim, who in the 1920s thought we all have ideologies which are based in our "situatedness" in the social scheme, or Standorsgebundenheit. Further, he emphasized a "relationism" that we all have to the truth, though no one owns the truth. There are those who are more free and open to exploration within other ideologies, and Mannheim thought they were the relatively unattached stratum of intellectuals, writers and artists. These people had a clearer view of the landscape and more sophisticated takes on "knowledge" "the truth" and "common sense." We can safely assume the better discourses around "common sense" would come from these types of thinkers. They will not come from C. Wright Mills's "men of affairs."

10The exact date/issue currently eludes me and I found this quote with something else I'd scribbled on a 4x6 notecard on "common sense" and the "self." Similarly, Marshall McLuhan supposedly has something in common with William Blake regarding common sense in that they both thought of human touch as the "sensus communis" and, at least for McLuhan, touch reintegrates our sense ratios which were thrown out of balance by various forms of media and their effects on the nervous system. Presumably we need this now more than ever, but I may have been stoned. This from a notecard fragment that looks written in the mood of ephemerality and possibly after waking from a dream. Sorry I even mentioned it.

11Email To The Universe, p. 179, Hilaritas Press ed, p.169 in New Falcon ed. "Damned Things" is a nod to Charles Fort, a major influence on Wilson's philosophy of science. The quoted passage is from an essay, "Damnation By Definition," which RAW traces back to his 1964 unpublished book, Authority and Submission. Note the term "prejudice" again here. RAW's deep study of perception informed his reading in General Semantics and led him to think that we literally don't notice substantial parts of the world that are right in front of our faces, because our brains have already decided what's "real" or worth paying attention to. This idea has gained enormous ground in the neurosciences since 1964.

12Quantum Psychology: How Brain Software Programs You and Your World, Robert Anton Wilson, pp. xxi-xxii, Hilaritas Press ed; pp.18-19 New Falcon ed. You wondered if Einstein would show up in "common sense" didn't you? Well here he is. Again: steal at least one idea here for your lively conversation about common sense:

Your friend Thaddeus: I remember some writer saying common sense was just some prejudice coming out of a dreary stone age bog or some shit.

You: Yes. Let's not forget to mention our inertial frames when making any statement involving a claim of space-time, as Einstein would urge us. Man, this Unicorn Poop is da bomb!

(Silky Sylvia walks in from another Substack screed): What're you guys talkin' about?

13Natural Law: Or: Don't Put a Rubber on Your Willy & Other Writings From a Natural Outlaw, Wilson, pp.72-73, Hilaritas Press ed; p.59 original Loompanics ed. Man, this "common sense" thing is gettin' out in the weeds, eh?

14Philosophy at 3 a.m: Questions and Answers with 25 Philosophers, ed. Richard Marshall (2014), Oxford U. Press, p.39.

We have a 34-time convicted felon as a leader, and his ideas are endorsed by more then 50% of the "representatives." In addition, the felon, who has always seemed to me more like a needy screaming toddler than a fully rational-emotional adult, was allowed to appoint three Right-Wing authoritarian Christian ideologists to the highest court of law in the land. I won't go into more details.

What I have just written, to the degree you assent or not, was solely from my subjective point of view. It's my best general take as of today, but I'm still learning. I don't think my interpretation of this reality is the one true correct one; I'm only trying to describe what I have seen. Your interpretations will differ in some significant ways. I will try not to go into more details about why I think these things. In my understanding of epistemology, I could be completely insane, but "sane enough" to have a Substack and to be writing somewhat coherent English sentences. I think I "am" sane. Others say so. I think the felon's minions and adherents entertain ideas that, taken to logical extremes, are mostly needlessly stupid and cruel, and lead to human misery for most people. And I've found when daydreaming I feel like I somehow lack an adequate metaphor for this entire scenario.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

History teaches us that cruel despots are more the rule than the exception. What that says about history and humanity I'll leave to some other blogspew. For now I'm trying to grasp at something better than "The Darkness." So I'm going to name some writers and ideas and pre-existing metaphors, and, like the way metaphors can work, try them on for size and do some comps.

Embodied MetaphorTo be extremely brief, I'm heavily influenced by the work of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, who, looking at metaphors as mostly invisible conceptual systems that guide our thought, found what philosophy and linguistics were saying about metaphors inadequate, so they lighted out for a new territory, c.1979.1 They say that the idea of metaphor as a poetic flourish that we can use if we want for rhetorical purposes is completely wrong: metaphors are conceptual systems that give rise to action, and are detected by analyzing language. Notice the "buried" sense here: the words are on the surface; the action we take in even our most mundane moments were driven by unconscious metaphors that are instantiated in neural clusters.2

So as I grasp for something I feel is a sufficient label for the world we live in in the U.S, late 2025, I feel it's almost darkly whimsical; I'm acting from a poetic impulse that elides the main points Lakoff and Johnson wanted to make, while here I am at the same time claiming that whatever I come up with will still fall within their frame of what accounts for as metaphorical. I mean: Who the fuck cares what we call it? Will it clarify things enough to spur action? Or help move things towards something more "sane"? I have grave doubts. I don't think it will make a drop of difference. Hence, my claim for a dark whimsy here.

"Black Iron Prison"This was Philip K. Dick's idea of an omnipresent system of social control that obscures the true nature of things. It showed up originally in his late novel, VALIS, and was floridly elaborated upon in his notes for his gigantic, sprawling Exegesis. It's a gnostic view: to wake up and see slave labor, manufactured wars by the strong against the weak, mass surveillance of every aspect of our lives, bread and circuses, etc: PKD thought the Empire Never Ended. (Roman empire). Are we "in" this place?

A quick elaboration can be read here.

Why this feels inadequate to me: while the political views here seem true, there have been some oscillations historically. It looks dire now, but it always looks that way to the literate in very Bad Times. I'm not sure we're in something this bad, though many of you may disagree. My own situated-ness is precarious and yet I've trained myself to enjoy the simplest of things. At a micro-level, my own life is a happy one. Perhaps I'm fooling myself? I don't know. It's still a wonderfully menacing idea from PKD. It's up to us to wake up and see it, and realize there is some spark of divinity in everything and presumably if enough of us realize this, we can defeat it.3 It's very complicated and PKD was a substantially complex man.

I might be resisting here. I'm uneasy with my existential stance: that so far ICE hasn't come for me; so far my medications are still covered; to this point I can still afford food; so far there are no blackshirts out disappearing "liberals" who showed up on a list that probably emanated from Palantir, etc. I will be in solidarity forever with those victims of wanton, needless cruelty, and indeed, It, whatever It is, does seem to be gunnin' for me, because, while white and native-born, I am not rich. Not even close. So I may have false consciousness here; the Black Iron Prison may be accelerating towards its Endgame. If so, I fear for my own looming fearfulness and would like to think I will remain mostly fearless, but have grave doubts. The Overseers are fabulously wealthy and powerful, but it's not enough because so far all that wealth and power has not made them happy. Do any of them seem happy to you? Like they've got genuine interests outside "winning"? They do not to me. Not a one of 'em.

Do we live in the Black Iron Prison?

(Pessimistic-Existential)"Labyrinth"

(Pessimistic-Existential)"Labyrinth"I grew up in the suburbs of Los Angeles but in my twenties I found I was completely enthralled by films noir, especially ones from what critics call the "classic cycle," 1940-1960. Hard-boiled gumshoes, fedoras, high contrast lighting, femmes fatale, endless hierarchies of crime where often the low-level street thug is part of a larger system leading to a "fine and upright" millionaire corporate head or mayor. After 1960s noir films were always made and still are. They were made before 1940, but that's not my point. The ones from the classic cycle were heavily influenced by refugees from fascism in Europe, and they worked within the studio system and slyly wrote codes into these films that contained messages that went 180 degrees against the American myth of "If ya just work hard and be a good person things will work out for you." Just look at some of the titles: Desperate, Trapped, No Way Out, Detour, Criss Cross, Brute Force, Roadblock, etc. A common theme is the simple working man just happening onto some situation in which he becomes entangled or ensnared, which leads to murder, blackmail, mistaken identity, and all varieties of prisoner's dilemmas, and, as a line in Detour has it, "Fate, or some mysterious force, can put a finger on you or me…for no good reason at all!" The concrete canyons - the labyrinths - of our metropolises - especially Los Angeles and New York - are where the ongoing summations of primate human emotions play out. Organized and disorganized crime, money, sex and greed, violence, toxic egotistical misery-bringers and other exotic varieties of sociopathy, corrupt politics…these all play out against our desires to just keep to ourselves and live quiet, decent lives of somewhat meaningful work and social volunteerism, a white picket fence in front of an orange tree in the suburbs, mutual aid, and self-creation. In other words, in the labyrinth, it's near-impossible to live such a life. In these films, capitalism is the hidden engine of widespread psychopathy.

There are stories you were told and then there is reality, which, in one narrative that's always intrigued me, the only children who are told about "reality" are the children of the rich. I'm not sure if it's true, but there's a lot of truth in it. Being not born into wealth, I had to jump outside of my own reality-tunnel system and look at other realities. This one - the world of the wealthy - seemed in itself noir as fuck. We're rich because we are the Best People. But also: we're rich because, let's face it: you take all you can and give the other guy the shaft and that's just what Grandpa or Daddy did; that's simply the way the world works. Law of the jungle. Don't let anyone tell you otherwise. Don't fall for the stories the Poor People (who deserve their lot) tell, about fairness, kindness, egalitarianism, and community: that's for the weak. In this narrative, the children of the rich grow up with two different worldviews. Can one be happy that way? I'm not sure. I suspect not.

Very often in films noir the small town or rural area is seen as an escape from this madness. From the nighttime shots of long shadows and murky characters plotting in dingy tenements or boardrooms in the City, to the sunshine and trees and fields of the small town and a sudden simple sweet melody in a major key promise refuge. But you're a sap if you don't think they can find you, track you down, and keep you ensnared. Even out there, where grandma lives.

Noir's labyrinths: mazes in the impossibly complex City, possibly leading to the Abyss, to death or insanity: as a young person I found I needed these films to help me overcome the attenuated, tunneled varietals of "reality" I had made from green, quiet, drab, lower-middle-class swimming-pool-drenched suburbia. It was as if I had found a huge piece of missing "reality" that I always knew existed and now I had the cognitive capital to understand the deeper levels - the metaphors - of what these films "mean." The filmmakers - especially the writers of the source material - were critiquing the American myth and the only way they could get it on the screen was the real-world spectres of Franco, Hitler, Mussolini. The gangster capital of the English-speaking world felt threatened by the type of capitalism the fascists were promising, so once again, you're off to "Over There."

The films were disturbingly enjoyable. They were (and are: I still re-watch them obsessively) a certain type of education.

It's a truism in noir studies that the people who made these films just thought, "we're making yet another crime film." They never said, 'Let's make a film noir." The term "film noir" was invented by French critics after the American films began to filter into Paris after 1945. It's funny4 how others can reframe your reality by seeing it from a different vantage point.

Are we in an endless noir labyrinth? You tell me. Closely allied to this…

"Chinatown"A neo-noir film that came out in 1974, the authoritarian Production Code had evaporated due to the film industry's de-monopolization and need to compete with television, Chinatown (1974, Roman Polanski) had the very bleak ending that had not been allowed by the infantilizing Code. The Bad Guy, "Noah Cross," played by John Huston - an obscenely wealthy man who has literally created a teenage girl from incest (imagine a rich-man-leader who lusts after his own daughter!) gets away with everything. In other words: reality. It's a naked lunch: Burroughs supposedly defined that as finally, clearly seeing what's on the end of your fork.

In the film, ostensibly about a private eye in Los Angeles in the 1920s and the history of the real estate/water-swindle in the City of Angels, "Chinatown" is that area of the City in which you don't know the language or the cultural codes. You really don't know what's going on. As the books I read as a child called it: "topsy-turvy." The cops would seem loathe to mention that they can't figure out what's going on there, but you know they talk amongst themselves. And think of the metaphorical possibilities here, in "Chinatown." You must pretend, play-act and fake it if you're a non-Chinese person. 'Cuz things are going on and you know not what or who, or why. It's another realm of reality: an opaque one. It's something horribly sobering to encounter if you're charged with "keeping order."

Not long after the film came out, the director, Roman Polanski, gave an interview with Der Spiegel. They asked him about the significance of "Chinatown.":

The title simply represents the film's mysterious atmosphere. Jack Nicholson's detective character has experienced something important and disturbing - the violent death of a woman. Now he meets a new woman, who has something threatening and important about her, something that's somehow Chinese in nature. […] Chinatown, whether it refers to a place or the woman, represents Nicholson's fate, something he keeps having to face up to.5

Robert Anton Wilson was an Adept at naming these metaphorical states of mind. He had written about Polanski having to dodge the Nazis in Warsaw and having his pregnant wife ritually murdered by the Mansonoids, and entering "Chinatown" both times. An extended metaphor. The script was written by Robert Towne, who grew up in Los Angeles and he had similar metaphors for "Chinatown." Wilson used the "Chinatown" metaphor in his novel The Universe Next Door. An FBI agent has been surveilling and bugging Justin Case, who bears some similarity to Wilson himself:

Special Agent Tobias Knight, playing Case's tapes one evening, actually heard a long rap about Curly being the id or first circuit, Larry the ego or second circuit, and Moe the superego or Jung's fourth circuit. Things got even more confusing when Case went on to talk about the "cinematic continuity in the S-M dimension between Moe and Polanski." It got even weirder when Case said, "Polanski himself went to Chinatown three times — when his parents were murdered by the Nazis, when his wife was murdered by the Manson Family, and when he got convicted of statutory rape. We all go to Chinatown, one way or another, sooner or later."6

The FBI agents have no idea what to make of this.

Wilson later has Case argue briefly that Skull Island in King Kong, was director Merion C. Cooper's "Chinatown." We know that Cooper had been shot down in 1918 during World War I, and he put the plane in a tailspin to suck the flames out, was taken prisoner by the Germans and thought dead by the Army. In another novel, The Trick Top Hat, Case is dreaming of lecturing about film to an audience of transvestites:

The montage of Chinatown or Chapel Perilous takes us to the Lair of Fu Manchu - the center of Power - the occult Nine Unknown Illuminated Ones who rule the world -the secret of capitalism and ownership - the cruel Cross that separates inside from outside, without windows.7

Here Wilson conflates the Chinatown metaphor with his favored, very similar metaphor, Chapel Perilous.

"Chapel Perilous"Originating with the Grail stories, with many versions related in Jesse Weston's magisterial From Ritual To Romance (1920), Wilson had probably first encountered this metaphor there, when reading supplementary material for Ezra Pound or TS Eliot. He saw the need of this metaphor when he thought he was losing his mind or was contacted by extraterrestrial intelligence, starting around July of 1973. He later entered Chapel Perilous when his teenage daughter was murdered in 1976. His interpretation of metaphorical place is robust and compelling:

In researching occult conspiracies, one eventually faces a crossroad of mythic proportions (called Chapel Perilous in the trade). You come out the other side either a stone paranoid or an agnostic; there is no third way. I came out an agnostic.

Chapel Perilous, like the mysterious entity called "I," cannot be located in the space-time continuum; it is weightless, odorless, tasteless, and undetectable by ordinary instruments. Indeed, like the Ego, it is even possible to deny that it is there. And yet, even more like the Ego, once you are inside it, there doesn't seem to be any way to ever get out again, until you suddenly discover that it has been brought into existence by thought and does not exist outside thought. Every thing you fear is waiting with slathering jaws inside Chapel Perilous, but if you are armed with the wand of intuition, the cup of sympathy, the sword of reason and the pentacle of valor, you will find there (the legends say) the Medicine of Metals, the Elixir of Life, the Philosopher's Stone, True Wisdom and Perfect Happiness.8

The Veil of Maya, Blake's "Dark Satanic Mills," Gurdjieff's civilization of sleepwalking madness, the Discordian's "Region of Thud," David Lynch and Mark Frost's "Black Lodge," the list goes on and on. You probably know others from your favorite artists and writers.

The historical moment at the end of 2025 in the US feels like a bit of all of the above-named. Some wonder if an entire culture can be in Chapel Perilous. I would assume so; there are no rules for these things. They all seem to function as a metaphor for Stephen Dedalus/James Joyce's "Nightmare of History." I think we all need intuition, sympathy, reason and valor if we're going to make it through this.

Poe's "Descent Into the Maelström"A science fiction story from 1841, a man tells how he survived being caught at sea in a massive whirlpool, a vortex never before seen by anyone. The drowned ship was pulled under. One brother went instantly insane, the other disappeared under the water, objects around the narrator were repelled and attracted by the mind-numbing physics of the storm. Suddenly, he had a revelation: as terrifying as this was, it was magnificent, even beautiful. The narrator abandoned ship and clutched a barrel and was rescued by fisherman.

The point was: rather than panic, he calmed down and observed. This story gave Marshall McLuhan an idea about how to observe the effects of media while being a part of the culture in which the dizzying effects of media were playing out.

Can we create or locate some standpoint in which to see…"all this" more clearly and calmly?

1Metaphors We Live By is one of a few "high culture" texts that have not only been stimulating and interesting to me in the extreme, but has reliably given me a low-level psychedelic buzz ever since I first encountered it.

2The neural clusters, or circuits, got there by once being children in environments. If we must divide political worldviews into something like Authoritarian patriarchal hierarchy or Nurturant co-parent general views, as Lakoff does in his Moral Politics, it's because we were exposed to both of these worldviews very many times as children. Lakoff uses the term "biconceptual" and we are all this: we all understand the other view while mostly not adhering to the other concepts; in actual practice most of us seem a mixture of mostly one metaphorical cluster and a little of the other. We're all "bi." The neural circuitry was built-in from there, and as we grew up, we continued to be exposed to both types of political metaphors. When we watch a movie in which a "justice"seeking vigilante takes the law into his own hands and murders the bad guys: the Authoritarian circuits get buzzed and are strengthened; when we teach our children to stand up for or protect that one kid who is being bullied because it not only helps that kid but makes us better people, that's the Nurturant model being buzzed and strengthened. There are a gadzillion examples.

3This idea is a classic gnostic one and yet I'm still waiting for enough people to demand single-payer Universal Health Care like they have in all true civilized countries, so this general millennialist wake-up call seems very much like Sky Cake to me right now.

4"funny" as in ironically and interesting in its dark implications, not "funny" as anything coming from mirth.

5Roman Polanski: Interviews, U. of Mississippi Press, pp. 60-61 (2005)

6Schrödinger's Cat Trilogy, omnibus ed, p. 23

7Schrödinger's Cat Trilogy, omnibus ed, p.273

8Cosmic Trigger I: The Final Secret of the Illuminati, p.4 (Hilaritas Press ed.) If you noticed the metaphors upon metaphors found here, you're not alone, and it was for a reason. See my colleague Gabriel Kennedy's biography of RAW for more details on his entrances and extrications from: Chapel Perilous: The Life and Thought Crimes of Robert Anton Wilson

"What variety of herbs soever are shuffled together in the dish, yet the whole mass is swallowed up under one name of a sallet." - Montaigne, On Names, Chas. Cotton translation

Okay, I gotta admit it: I've long had a thing for Naomi Klein, and when her book Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World came out I had to read it. Either I nominated it for the book group I'm in or someone else did. I would have read it anyway. I love her. Anyway: Klein takes off from how she was increasingly confused in the wider culture with Naomi Wolf, who had slowly gone from feminist icon to…whatever you call what she is now: "influencer"? Regressive, neofascist anti-vaxxer? I don't know. I find it depressing. Klein: "There is a certain inherent humiliation in getting repeatedly confused with someone else, confirming, as it does, one's own interchangeability and/or forgettableness."1

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

While reading Klein's book I recalled some of the times I'd mixed up names. Sometimes I think it's sheer laziness on my part (yours too?), but I also think we are increasingly exposed to so many names these days we're bound to get convoluted and intertwingled every now and then. Recently I had realized I was reading two different left-ish culture critics and writers instead of one guy: Branko Milanovic and Branko Marcetic are different people! "He" was simply "the Branko M-ich" guy until I realized…

I had read a lot of literary journalism from the scholar of Literary Modernism/OSS-linked biographer of James Joyce, Richard Ellmann, whose bio of Joyce is often named with Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson as the most influential biographies of all-time. But later I realized some of this was Richard Elman, one enn, one ell: a novelist, journalist, poet and teacher. Different dudes. I only know of one Ellmann who writes. Turns out there are two, both named Richard. Perhaps there are Richard Ellmans I haven't found yet? Why did I not notice the doubled letters not being there with the novelist guy? What are some of your own examples? I admit I thought the second one-enn/one-ell guy's style-change kinda vexing until I realized…

Here's a question for you: How many people with the last name "Brodie" do you know? I know no one personally with that name, but I'm a film noir fanatic, so I know Steve Brodie from a number of wonderful noirs (Out of the Past, Armored Car Robbery, Desperate, Crossfire). Then around a year ago I was reading a bunch of stuff about the discovery of peptides and the endorphin system, and I glommed on to Candace Pert, who had a wonderful terrible genius life. She worked under the venerable neuropharmacologist Solomon Snyder at Johns Hopkins. Snyder worked under Nobel winner Julius Axelrod, who made seminal contributions around dopamine, catecholmines, epinephrine, and the pineal gland. Axelrod worked under the legendary Bernard Beryl Brodie, who did pioneering work in neurotransmitters, anesthesia, paracetamol, and Tylenol. You say: so fucking what? That's just another Brodie. He doesn't have the same first name as your noir dude. Oh, but for some reason his friends called this Brodie "Steve."2

In 1886 an earlier Steve Brodie claimed to have jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge and survived. An early influencer, this Steve Brodie was responsible for that time you went head-over-heels in a bicycle crash: it was called "doin' a Brodie" when I was a kid. Or maybe you just took a flying leap at something that seemed a last-ditch effort: a Brodie. I think I first encountered this Steve Brodie when Bugs Bunny mentioned him.

So: I can't think of any other Brodies off the top of my head (maybe the old 49ers QB from the 1960s, John Brodie), but here there are: three all-Steve Brodies. Perhaps the notoriety of the Bridge-jumper (he probably didn't jump but wanted people to think he did) influenced the other two.

This seems weird to me, but not as weird as nomen est omen, or "nominative determinism," "the name is the sign," the idea that your name influences who you become as a person. Which seems, on the face of it, insane.

Nominative DeterminismI live near Santa Rosa, California, and when I listen to local radio stations I'll often hear an ad for Grab 'N Grow, a company run by Soiland. Started in 1962 by Marv Soiland, the Soiland Company specializes in soil, mulch, and compost. Their motto "We're as old as dirt." Why did Marv get into this business of dirt? You wonder. This reminds me of a George Carlin bit: there was someone who cleaned up in dirt farming, but later the market went south and he took a bath and had to wash his hands of the whole thing.

This phenomena got a lot of play from a 1994 New Scientist article about a polar explorer named Daniel Snowman, and two urologists named Splatt and Weedon, although Jung was interested in this (of course) and noted his former mentor, Freud, who studied pleasure, had a name that means "joy" in German.

The bass player for Rush, Geddy Lee, wrote about his Jewish heritage and the Holocaust in his autobiography. He cites the Bronfman family in Canada: a Moldovan Jewish Canadian family of bootleggers in the 1920s. They later morphed into Seagram's, went legit. Bronfen is an old Yiddish word for booze, moonshine, spirits. Lee cites Prohibition scholar Daniel Okrent: "It was almost fated that the Bronfman family would make its fortune from alcoholic beverages."3

Freud's disciple and writer on sex, Karen Horney? Michael Pollan, who writes prolifically on flowering plants? The misanthropic writer Will Self? Self wrote about Wittgenstein's ideas about how your name might influence your personality. The botanist who discovered the sexual-reproduction parts of the flower: Nehemiah Grew. Agnes Arber was an early 20th century botanist. A few months ago I was reading on intellectual culture and in a George Scialabba essay he wrote about a Neo Conservative intellectual who can't stand intellectuals, calling them "feckless, resentful, unworldly, and power-hungry." His name: Robert Conquest.4 There was a pretentious asshole at Harvard who kept women out of the Experimental Psychology department, because this guy, Edward Boring, thought it was a man's discipline.5 There's a theory about the earliest singing ever done on planet Earth: by a specific weird fish, and the idea comes from Cornell professor Andrew Bass.6

Three names of the fastest male sprinters over the past 50 years: Houston McTear, Harvey Glance, and Usain Bolt.

In researching all things Giordano Bruno I can't help but think about one of heaviest persecutors of Bruno for his ideas: Cardinal Severina.

A name-story that I find haunting: the lead singer of the hair metal band Warrant took a rock star name: Janie Lane. His parents, the Oswalds, had named him John Kennedy Oswald; he later changed it to John Patrick Oswald. A "pretty" man, Janie Lane later told a story to intimates about a famous musician and that musician's manager on the Hollywood metal scened who drugged him and raped him just after Lane arrived on the Sunset Strip metal scene. A well-liked and talented musician, he drank himself to death at age 47. As far as I know, this story/case/allegation is still a mystery. I wonder about how having the name John Kennedy Oswald may have scarred him in some way; maybe I'm just reading too much into it, like some cut-rate palm reader.

One of the most informed writers on how the nuclear stockpile and our readiness to start nuclear war threatens all living things: Elaine Scarry. In Austin, Texas, there's a doctor who specializes in performing vasectomies: Dr. Richard ("Dick") Chopp. The guy who invented the hottest pepper in the world, the Carolina Reaper, is named Ed Currie.

There seems to be more surgeons named Dr. Pain than statistical chance would allow, but who knows what's really going on?

Any one of us can name a few more I haven't mentioned. Are these all merely a coincidence? What precise mechanisms would explain this? If you do a deep dive into nominative determism you will read articles about how there are statistically more dentists with the first name Dennis, and how if you're a Baker you're almost more likely to bake.

It can get perilous. A man changed his name to Beezow Doo-Doo Zoppity Bop-Bop and was arrested for a drug offense. On the other hand, Marijuana Pepsi Vandyck, a truly Pynchonian name, earned her PhD in Higher Education. Her dissertation was on uncommon black names in the classroom.

How Might Nominative Determinism Work?We're not noticing all those people whose name has nothing to do with their occupations or ideas. So, clearly there is no "determinism" here. At the same time, I wonder if some poetic aspect of words, in some farther-flung Whorfian sense, work on some people's subconscious and it influences them, while if you ask them, they say their name had nothing to do with why they pursued this or that line of work. Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Igor Judge, said his name had no influence in his pursuit of the law; a weather reporter named Storm Field said the same, although his father, Frank Field, also a weatherman, influenced him. All dad had to do was add the Storm, and voila! Perhaps there are some forces of convergence also.

In all, these names and occupations are good for a laugh, and seem to function in the way that Henri Bergson said humor works: it reminds us that a lot of the time we're acting as if we have no agency. Humor wakes us up to this. We are not robots, though a disconcerting amount of time we act like we are. As Oliver Hardy so often said to Stan Laurel: "Now see what you made me do!"

Brief Remarks on Having a Boring NameThis past October 23rd, 2025 I watched Jeopardy! (being an incurable addict) and one of the contestants was a long-hair, uniquely dressed young man with a baritone voice, who identified as a poet. His name: Elijah Perseus Blumov. I was quite jealous. Of his name. (By the way: he didn't win, though I was rooting for him and his name.) I've long wondered how to get out of the bland anonymity of my birth name: Robert Michael Johnson. I was named after my dad, but mom and dad called me by my middle name. Currently Johnson is still running second to Smith for surnames in the US. I write a lot about Wilson, whose name is 14th on the latest census list, behind Gonzalez, but just ahead of Anderson. One of my best readers of this Substack is Jackson, currently number 19. Another is Campbell, who comes in at number 47 as of the 2020 census. If any Williamses, Browns, Joneses, Garcias or Millers are here: welcome! You too, Davis, Rodriguez and Martinez.

The philosopher and Leibniz scholar Justin Erik Halldor Smith later just signed his articles Justin EH Smith, but now he's Justin Ruiu, and he explains why here.

When I was in junior high school there were three Mike Johnsons, including myself. It was then (age 14) when I realized I had to deal with this horrible name. If I go by my birth certificate, I'm Robert Johnson, who…is the king of blues guitar. He went down to the crossroad, fell down on his knees, made some sorta deal with Satan to become the best guitarist, and it worked. Okay!

I had a doctor who made the same "Do you play blues guitar?" joke every time I saw him. He just must've forgot, for obvious reasons. What's weird is: yes, I do indeed play blues guitar. I know the current leader of the fascist party in the House has my name, but it will blow over. For awhile, Michael Johnson was the fastest man in the world. You probably know someone else with my name. Naomi Klein? You had just enough Naomi to get into trouble with another one. My troubles along these lines are relatively dull.

When I got married in Hawaii there were a few options for changing your name with marriage, but one that they didn't allow in that state was for the man to take his wife's last name, which I actually tried before they told me I couldn't do it. I couldda been Michael Canada. I couldda been a contenduh!…for something less forgettable.

I've long thought of just adopting a nom de plume, and I can't give you a good reason why I haven't yet. Perhaps on some level I'm too mired in the name. There's so many of us it has a certain black hole-gravitational pull to it. Or seems to. This lifelong name is getting me almost zero traction as a writer. So: maybe I should find something more memorable, more musical or picturesque or grotesque or poetic. Right now I'm partial to Elijah Perseus Blumov, but I hear it's already taken.

I sometimes wonder if I became a Generalist because of my name. Ya know, like Dr. Dick Chopp, became the vasectomy king?

1Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World, Naomi Klein, p.27

2If anyone reading this is interested in how influential first-person chains of scientific research works you might do no better than read Apprentice To Genius, by Robert Kanigel, which goes into great detail about why one location (Johns Hopkins) could generated Brodie to Axelrod to Snyder to Pert.

3My Effin' Life, Geddy Lee, p.15

4What Are Intellectuals Good For?, George Scialabba, p.162. Also see, p.49, and the oft-complaining Walter Karp and writers who end up writing about what their names sound like. Scialabba links this to Derrida's ideas.

5https://daily.jstor.org/gatekeeping-psychology/

6Beethoven's Skull: Dark, Strange and Fascinating Tales From the World of Classical Music, Tim Rayborn, pp.153-154

(artwork by Campbell)

With the rise of mass media and literacy in the first half of the 20th century, the disparity between utopian feelings around 1900 and the Great War only 14 years later, followed by fascism, another world war, the Bomb…we also became very aware of espionage. This will be the first of a series of essays on the topic of writers and artists and the security state. There's something about imaginative writers and the craft and game of intelligence that has them overlapping in so many strange ways…

(artist unknown)

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Anarchist Bombings in the USUnited States, May Day, 1919: mail bombs sent by anarchists to prominent government agents explode. The following month: ten bombs explode in New York, Cleveland, Milwaukee and San Francisco. In DC, a man carrying a case to the attorney general's house trips and a bomb explodes in the yard. Glass everywhere. Later police find what was left of the bomber's head on the roof of a three-story mansion a block away. This is linked by authorities to Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, who was quickly deported. Attorney General J. Mitchell Palmer amasses a security force four times larger than what is was during the Great War. The enemy: Reds. Bolsheviks, communists, weirdo bohemians and free-thinkers or anyone who seemed like they may be one. The infamous Palmer Red Raids ensued. A new, very small bureau in DC, the General Intelligence Division - soon to become the FBI - helps to suss out writers and publishers, files, books, magazines, newspapers, anything that sniffed of "radical literature." A very small avant literary magazine, The Little Review, gets busted. It's run by two arty lesbians who were attracted to Gurdjieff, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. They had been printing chapters of James Joyce's upcoming novel, Ulysses. It was the only platform for Joyce's book in the US. Now Joyce had a file at the nascent FBI.1

UnabomberAs Theodore Kaczynski's bombs increasingly did more damage, the FBI was stymied trying to figure out who this guy was. Kaczynski was toying with them: inserting false leads, wearing elaborate disguises, taking long bus trips to mail his bombs from disparate locations, he even found hairs in public urinals and inserted them into his packages to throw forensics off the trail. Kaczynski also teased the FBI with wordplay and they didn't know it for the longest time. Let's look at how he used the word "wood."

His bombs came in wooden boxes. His third victim was named Percy Wood, who lived in Lake Forest. The tenth victim lived in Ann Arbor. His 16th victim worked for the Forestry Service, and was mailed from Oakland, California. The sixth bomb was sent with the name of a real Brigham Young professor, Leroy Wood Bearnson. A writer at the San Francisco Chronicle, Jerry Roberts, received a letter from the Unabomber, who signed himself "Isaac Wood" of 549 Wood Street, Woodlake, CA. The wildest example, to me, is when the New York Times received a letter from Ted K in the early summer of 1993, which provided a social security number: 553-25-4394 as a way to prove it's really him if he writes again in the future. Of course the data base for social security was consulted: this number was linked to an inmate at Pelican Bay prison in California. When officials approached the inmate, he knew nothing, of course.

But on his forearm there was a tattoo: PURE WOOD. I still can't figure out how Kaczynski pulled this off.

Kaczynski, a former Prof of Mathematics at Berkeley, who wrote his thesis on "Boundary Functions" (don't ask me!), knew Nordic and English language histories. In 1995, William Monahan of the New York Press, figured out that the Unabomber was using Old English: "wood" in its earliest usages, meant, "the sense of being out of one's mind, insane, lunatic." In Chaucer, when people "go wood" it's because they've tricked. "Wood" was used when someone was bested by an intellectual superior. Monahan explained to the FBI and anyone else who would listen, the "going wood" was a triple entendre: angry at being tricked, numbness from trauma, and getting an erection.

And that was just part of the wordplay, Monahan suggested. For example, the package containing the bomb that killed Thomas J. Mosser of New Jersey listed a fictitious name, "H.C. Wickel," as the sender. In old English, the word '"wicker" means wood. "H.C. Earwicker" is a ubiquitous character in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, who sometimes assumes the identity of the Norse god Woden.2

Kaczynski had signed some missives and his manifesto "FC." It took awhile to figure out what this meant. It meant "Freedom Club" and it was taken from one of Kaczynski's favorite novels, Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent.

Mail bombings, espionage, counter-intel, artists, false leads, intellectuals, and codes.

No Such Thing As Bad Publicity?In a September 1920 letter to his brother Stanislaus, James Joyce wrote that there had been "reports" of himself as a spy in Dublin for the Austrians, as a spy in Zurich for the British or Sinn Fein, that his Ulysses was a pre-arranged German code, and that he was a cocaine addict. Sometimes I think Joyce was an all-timer at starting whispering rumors about himself. I suspect he was fascinated by how rumor worked, which was a lot like a virus.

Other rumors he'd heard about himself: he founded Dadaism, was a bolshevik propagandist, and "the cavalier servant of the Duch—--of M—--, Mme M—-R——M—-, a princ—de X——, Mrs T-n-T A—- and the dowager empress of China."3 A few months later his prime benefactor, Harriet Shaw Weaver, wrote to express concern over Joyce's excessive drinking. Apparently she'd heard stories from Robert McAlmon and Ezra Pound. Joyce's reply to Weaver, dated June 24, 1921, is a study in disinformation between a writer and his sponsor: Joyce denies much while relaying other scandalous rumors about himself, which he denies, while also admitting to being and doing the kinds of things that Artists must do. Joyce scholar Richard Ellmann writes that Joyce "countered legend with fact and fact with legend."4

Sylvia Beach reminisces about hanging out with Joyce in Paris:

He told me how he had got out of Trieste when the war came. It had been a narrow escape. The Austrians were about to arrest him as a spy, but a friend, Baron Ralli, obtained a visa just in time to get his family out of the country. They had managed to reach Zurich, and had stayed there till the end of the war.5

We wonder how many variations on this story Joyce told.

As many Joyceans observe, Joyce inserted his own fears and fetishes, dreams and obsessions in Leopold Bloom and HCE, (not to mention the antics of the Gracehoper-writer-artist layabout Shem the Penman) albeit exaggerated much of the time. One really doesn't know what's really true and to what degree, or how exaggerated his own weirdness was in these characters. Quite a lot of this strikes me as Joyce's antic humor, but what do I know? It also further serves to illustrate Joyce's understanding of the theory of relativity on a social or human scale.

This is all within a subset of difficulties in already notoriously difficult texts. Scholar Mark David Kaufman notes about the rumors Joyce recounted around being an alleged spy, and Ulysses: "The image of Ulysses as a book that seems to be hiding something, a book that may or may not be treacherous, has had a bizarre afterlife in popular culture. In The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Frank Sinatra's brainwashed character owns a copy of Ulysses. Similarly, in Robert De Niro's CIA film, The Good Shepherd, a KGB double agent hides his real identity papers in the binding of Joyce's novel."6

Claire Culleton traces "difficult" writers like Joyce, Woolf, Elliot, Pound to a general feeling, articulated by Llewelyn Powys in article in New Masses, in January 1927: "The average man would gladly kill artists for sport, for like fleas and bugs and lice, they disturb his sleep." Culleton thinks this aptly describes the conscious orientation of J. Edgar Hoover (who had to cover for his own homosexuality). For Hoover, the average Joe and Josephine America felt anxiety over the writings and paintings of these weirdos, and they had to be reigned in. Hoover wrote much intelligence lit-crit, which is perennially the most clueless in the lit-crit genre. Conservative guard dogs speaking on behalf of an insensible horde: Culleton thinks this ironically privileged the High Modernists, and pushed intellectual modernism, "driven by its aesthetic of complexity."7

In literature, this notion of using difficulty in an effort to create new styles and forms is one thing, but evasions, plausible deniabilities, and self-mythologizing of the artist could be a form of defensive esotericism. The writer feels that he might be persecuted for what he writes, so he utilizes smoke and mirrors to obfuscate, and only the initiates are clued-in. In Arthur Melzer's book-long attempt to flesh out Leo Strauss's theory of esotericism in Strauss's Persecution and the Art of Writing, Melzer writes that a writer may write esoterically to avoid two evils: "either some harm that society may do the writer (persecution), or some harm that the writer might do society ('dangerous truths'), or both."8 Obviously, Ulysses was banned in the United States for 11 years after its release in Paris. Despite the difficulties, certain people quickly sussed out the naughty bits (that they could detect), and it was enough. After thirty-odd years of reading all things Joyce, I feel I have less of an understanding of him than when I started. Joyce himself was an Enigma Machine!

Ed Sanders: Writer as Intelligence-GathererClassicist but also a member of the proto-punk band The Fugs, Sanders's slim pamphlet, Investigative Poetry, advocates for writers to report journalistically in the form of poetry or verse, like the ancients did. He gives many examples. He also lists numerous writers who were persecuted by the State for their writing. Sanders presents a 180 degree mirror image of the spook: the poet/artist/countercultural gathering of intelligence and corroborating reports, including techniques (Sanders urges us to open up our own files on any subject that interests us, including our friends), and advice for dealing with dangerous, difficult people. His advocation of studying one's own notes to glean "data clusters" seems ultra creative and revelatory. The story on p.32 about Sam Giancana, Sinatra, Las Vegas and the CIA is a good example of what Sanders was up to. Sanders's biggest influence was Charles Olson, who had strong ties to the work of Ezra Pound, who was the idol of…the head of CIA counterintelligence, James Jesus Angleton, who had lunch often with his friend Kim Philby while not knowing Philby was a double-agent. When Pound was detained by Allied troops in Italy, his Pisan Cantos were suspected of being a secret code.9 Sanders was also heavily influenced by Allen Ginsberg, who similarly kept files on hundreds of topics, and once actually had lunch with Angleton.10

Investigative Poetry has been a major influence on the Overweening Generalist.

Did Joyce Know and Use Classic Ciphers and Codes?The answer appears to be yes. In the "Scylla and Charybdis" episode in Ulysses, Stephen argues about who the "real" Shakespeare was. Who actually wrote Shakespeare? And Joyce was well aware of a best-selling book by Ignatius Donnelly and the idea that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare.11 The sheer level and amount of fun Joyce had with Bacon-Shakespeare has inspired thousands of pages by Joyce scholars. Bacon had actually spelled out a biliteral cipher in his Of the Advancement of Learning, Book VI, chapter 1. This cipher was what fired Donnelly up in his hammy pursuit of the "real" Bard: Bacon.

Two of the most famous and sophisticated inventors of ciphers, Sir Francis Beaufort (d.1857), and Charles Wheatstone, who attributed his cipher to Baron Playfair (d.1898) may have been used by Joyce; all three names appear in Finnegans Wake:

The optophone which optophanes. List! Wheatstone's magic lyer. (FW, p.13)

Hark to his wily geeses goosling by, and playfair, lady! (FW, p.233)

in the end, the deary, soldpowder and all, the beautfour sisters (FW, p.393)

till they were bullbeadle black and bufeteer blue…(FW, p.511)

in blue and buff of Beaufort the hunt shall make (FW, p.567)

The problem here is that these ciphers work in a long enciphered text, and Finnegans Wake is not such a thing. Joyce scholar James Atherton insisted that Joyce acknowledged all of his influences by hiding them in his texts, and it seems safe to guess that Joyce enjoyed the ciphers of Beaufort/Wheatstone/Playfair within the context of the Bacon-Shakespeare stuff, but what about this passage in FW?:

I should like to euphonise that. It sounds an isochronism. Secret speech Hazelton and obviously disemvowelled. But it is good laylaw too. We may take those well-meant kicks for free granted, though ultra vires, void and, in fact, unnecessarily so. Happily you were not quite successful in the process verbal whereby you would sublimate your blepharospasmockical suppressions, it seems? (FW, p.515)

This is Shaun, the frustrated postman, conservative, the Ondt to Shem's Gracehoper, and feeling like an intelligence agent here, calling out the text, probably Finnegans Wake itself. "Isochronism" means appearing at regular intervals, which is crucial in a good substitution cipher. "Secret speech" seems obvious. "Disemvowelled" is a very common way to code: leave out the vowels. (Or: lv t th vwls) Joyce actually uses this tool in discussing what's in Bloom's drawer at his house on Eccles Street. "Sublimate" also seems quite obvious in this con-text. "Bepharospasm" is a spasm of winking, which we see in film after film and TV, when a character is trying to stay quiet and signal to another to "go along with this." Or: whatever I seem to be saying just now? Don't believe it!12

Where might Joyce have caught on to the cryptographer's bug? One guess: J.F. Byrne, Joyce's good friend in college. John Francis Byrne, AKA "Cranley" in A Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man.

John Francis Byrne (1879-1960)In A Portrait of the Artist, the budding consciousness of Stephen Dedalus is trying to articulate his own ideas about aesthetics, and he tells these to his sympathetic friend, Cranley. Cranley is based on Joyce's friend J.F. Byrne. They had known each other for a long time, but became close while both were at University College, Dublin. Byrne had actually lived at 7 Eccles Street, the address of Molly and Leopold Bloom in Ulysses, from 1908-1910, with two cousins, and one night in 1909, when Joyce had returned to Dublin they went out partying and came back to Byrne's house and Byrne had forgotten the key in another pair of pants, so he climbed over the wall…the same thing Bloom does at the end of the day in Ulysses. Byrne exiled himself from Dublin for New York in 1910 and became a journalist and worked as a financial editor at the Daily News Record in NY from 1929-1933 under the pseudonym J.F. Renby. But what's most interesting about Byrne here: he invented a "chaocipher" made from a cigar box, a few bits of string and odds and ends. He claimed it produced ciphers that were uncrackable unless the receiver had the key.