Today, the world is filled with conflict. Part of the problem is oil limits, but there are many other issues as well:

- Resources such as coal, lithium, and copper are also becoming more expensive to extract.

- Fresh water is often inadequate for the world’s rising population.

- Debt levels are very high.

- Complexity is very high.

- An adequate standard of living is becoming unaffordable for many people.

- The increasing world population leads to a need for more food and more paved roads.

These symptoms strongly suggest that the world economy is headed for a slow-motion collapse.

Figure 1. Overall pattern of today’s predicament, in an image by Gail Tverberg. We seem to be up near the top now.

Figure 1. Overall pattern of today’s predicament, in an image by Gail Tverberg. We seem to be up near the top now.

The system causing the problem is physics-based. Without enough affordable energy of the right types, the economy tends to collapse. This is the predicament we are facing today.

What should ordinary citizens do? I am not certain that there is one correct answer, or that I know it. In this post, I would like to offer some suggestions for discussion.

[1] Every day, give thanks for the many things you do have.We are at the peak of resources per capita. This means that, as a group, we have as many goods and services as any population that has ever lived. We also have lots of natural resources remaining. We have a huge amount of complexity, with many young people receiving university degrees.

It is easy to lose sight of how much we do have. Most readers of this blog eat a variety of food in the quantities desired. We live in homes that are heated in winter. Even today, many people around the world are not as fortunate as we are.

[2] To the extent possible, stay away from conflict yourself.The physics of the system will create conflict because the system must change if there is no longer enough oil to ship huge amounts of goods and services across the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. Perhaps a few highly valued goods and services can be shipped long distance, but patterns must change to put the production of goods and services closer to the consumption of goods and services. This is a major reason why countries are quarreling now.

There is no point in individuals strongly objecting to cutbacks in trade because today’s lack of oil supply is demanding these cuts. The only way one country can lessen the impact of the reduced oil supply is to push the reduction in indirect oil consumption onto another country, using quotas or tariffs on its imports of goods and services. Needless to say, pushing other countries down to benefit one’s own country is likely to create conflict.

Another issue is that with reduced oil and other energy supplies, governments cannot continue to provide as many services as they have in the recent past. They need to reduce the number of government workers in many departments. This is the reason for the many cutbacks by the US Department of Government Efficiency and similar cuts in other countries. It also means that benefit programs, such as those aimed at seniors, the disabled, or hurricane relief, will need to be reduced or eliminated in the future.

We can argue about which programs should be cut back first, but ultimately, all government programs will need to be cut back substantially. Just printing money to try to solve the problem will likely lead to inflation; money doesn’t solve the physics problem we are facing. Energy products of the right kinds are needed for every part of GDP; not having sufficient oil is likely to cut back the supply of goods produced using oil products, including food.

If you get involved in protests, or even in war, you will be putting yourself in harm’s way. And, in the long run, you are unlikely to gain significant benefits personally.

[3] Expect declining complexity in the future.There are many aspects to complexity:

- Much international trade

- Much debt

- Businesses with multiple layers

- Governments providing a wide range of services, including pension plans and health care

- Energy efficient vehicles

- Appliances that are designed to save energy

- Healthcare with many specialized physicians and high-cost drugs

- Agriculture with many hybrid seeds, herbicides, insecticides, and soil amendments

All these types of complexity will need to be scaled back in the future, but we don’t know precisely to what extent or how rapidly. We cannot go back to old solutions because these won’t necessarily be available. For example, we know from the past that if an economy no longer operates with horses and carriages, it will no longer make buggy whips.

We need to expect a rapidly changing world. Complex appliances we own will fail, and we will not be able to obtain replacement parts. Many drugs imported from Asia will no longer be available. Homes purchased with debt will be affordable by fewer and fewer people. We need to be aware of these issues and change our expectations accordingly.

[4] Expect fewer goods and services to be available in the future, and money to have less value.We are no longer moving to an ever-better world; we are moving (at least for a few years, perhaps much longer) to a shrinking world economy. Do not be surprised if home values drop and stock market values fall.

Saving money for the future makes less and less sense because fewer goods and services will be available to buy in the future. Even saving gold will not necessarily work around the problem of there being fewer goods to buy. For example, farmers and others involved in producing food will likely get food before others, to assure the continued production of food. This will leave less food for others to buy.

Electricity is likely to become intermittent in the years ahead. It would seem wise to stay away from purchasing condominiums that can only be accessed by elevators.

[5] Focus on the present, not the past or the future.In our current world, great stress is placed on planning for the future. For example, workers are encouraged to save for retirement, and young people are encouraged to take courses that will allow them to work in a well-paying occupation for the long term. This plan assumes that that the upward trend we have seen in the past will continue. We also expect that governments will be able to make good on their promises.

But we really cannot expect this pattern to continue for the long term. The best we can hope for is that what we have right now will continue. If a family member is lost, the remaining members will need to pick themselves as quickly as possible and continue as best they can. This is one reason an extended family is helpful in Africa. Such an approach will increasingly be helpful elsewhere.

Fossil fuels have made retirement possible. As fossil fuel availability declines, retirement is less likely to be available. Everyone will need to work as long as they are physically available. Thus, saving for retirement becomes a less useful goal.

[6] Living in groups, particularly family groups, will increasingly make sense.When things were going well, and wages of most educated people were high, it made sense for many people to live by themselves. If they had an argument with their spouse, picking up and leaving might sound like a sensible idea. The job of each spouse would be sufficient to pay for housing for each separately.

As the economy goes downhill, people will need to live in more compact housing in order to save on heating and transportation expenses. Multiple generations will increasingly need to live together. In the case of singles, they will increasingly need to band together. Government programs will likely not be sufficient to provide separate living arrangements for a mother with children or for elderly individuals in care homes.

[7] Young people should not go into debt for higher education.At this point, the US has educated far too many people with college degrees (and beyond) relative to the number the economy can afford to hire. With declining complexity, adding more college-educated workers to the pool makes little sense.

A better choice for most young people is a short course or certificate program leading to a useful skill, such as appliance repair or becoming a licensed practical nurse. Apprentice programs may also make sense.

If families are wealthy enough to pay for their children’s education, a few people with advanced degrees will probably be needed. There may be some solutions to today’s problems that can be tackled by these individuals.

[8] People will need to be more flexible in their career choices.As the economy changes, job availability will change. Demand for workers in many of today’s high-paying careers will likely decline. For example, fewer specialty physicians will be needed. There will also be a need for fewer college professors, fewer stock market analysts, and fewer computer programmers.

The most immediate new jobs will involve the demolition of infrastructure that is no longer needed, such as movie theaters, shopping malls, office buildings, and many homes. Some materials will likely be saved for reuse elsewhere. This may involve heavy labor. Smaller, more local stores or open-air markets may open. Jobs previously held by immigrants picking vegetables and fruit will also be available.

How does a person step down from a high-paid desk job to a low-paid manual labor job? I don’t know. But, somehow, we need to be thinking through this issue.

[9] People should focus on taking care of their own health through healthy eating and adequate exercise.I expect the healthcare industry will be forced to change. One part of the problem will be fewer imported drugs and medical devices; another will be that most people will be less wealthy. They will not be able to afford the enormous costs of today’s bloated US healthcare system. Somehow, the system will need to shrink back.

Fortunately, there is a way that people can become healthier, despite lower spending. People can cook their own food, instead of buying over-processed food available from grocery stores and restaurants. They can eat less meat than the average American eats, and they can stay away from sugary soft drinks. They can exercise more. Part of this exercise can take place by walking to more local markets.

[10] Planting a modest garden, as far as this is possible, is probably a good idea.Most people do not have sufficient land to plant very much in the way of food crops. In fact, a large share of my readers probably lives in apartment buildings. And most young people, attempting to live on their own, will not have space to grow food crops. The cost of buying land is likely to be high, and property taxes will need to be paid.

If space is available on property that is already owned, fruit trees that grow and bear fruit without the need for pesticide spraying are a good choice. These trees will likely take several years to get started. Potatoes are another reasonable choice, as are vegetables in general.

It is not clear to me that people who set out to operate a self-sufficient farm will have much success. They require a complex infrastructure to support them. Such farms are very vulnerable to robbers and generally don’t have good backup plans if something goes wrong, such as the farmer becoming injured. I wish these individuals success in their endeavors, but I am not optimistic that these farms will succeed beyond their first major setback. We need a bridge to sustainable agriculture, but it is hard for me to see one right now.

[11] Concluding Observation: Why standing back from conflict is a suitable approach.Most people have a completely mistaken idea regarding what oil limits will look like. They assume that oil limits will lead to very high prices or long lines at gasoline stations. They fail to appreciate that oil limits will arrive at the same time as many other limits, including affordability limits. They also fail to understand that prices that are too low for producers will bring down oil production quickly. In fact, too low oil prices, rather than too high, are the issue the world is facing today.

What oil limits really lead to is lots of conflict: among nations, among political parties, among people who feel that it is unfair that they have spent a lot of money on an advanced education but cannot find a job that pays well enough to repay their education-related debt with interest. As limits of many kinds mentioned in the beginning of this post are hit, today’s economy will need to greatly shrink back in size. Many governmental structures that we expect today, including the EU, the World Bank, and the UN, may disappear.

We don’t know precisely what is ahead over the longer term. Some people believe a religious ending is likely. Other people think that some of the research that is currently underway may eventually lead to a solution. Still others are concerned that some parts of the world will need to shrink back to a very low level, perhaps similar to hunter-gathering, before these economies can grow again.

Regardless of how things play out, it is the physics of the self-organizing system that determines what happens next. No matter how offended we as individuals may feel regarding what some political party or politician has done or has not done, individuals are not able to fix the system, except to the extent that available inexpensive energy supply allows such a fix. This is why standing back from whatever conflict is taking place seems to me to be a suitable strategy.

I predict that the world economy will shrink in the next 10 years. I think that this is bound to happen because of energy and debt limits the world economy is hitting. There are a variety of other factors involved, as well.

In this post, I will try to describe the physics-based limits that the economy is facing, related to diminishing returns of many kinds. The problem we are facing has sometimes been called “limits to growth,” or “overshoot and collapse.” Such changes tend to lead to a loss of “complexity.” They are part of the way economies evolve. I would also like to share some ideas on the changes that are likely to occur over the coming decade.

[1] The world economy is a tightly integrated physics-based system, which is experiencing diminishing returns in far more areas than just oil supply.When extraction of a mineral takes place, usually the easiest (and cheapest) portion of the mineral deposit is extracted first. After the most productive portion is removed, the cost of extraction gradually increases. This process is described as “diminishing returns.” Generally, more energy is required to extract lower quality ores.

The economy is now reaching diminishing returns in many ways. All kinds of resources are affected, including fossil fuels, uranium, fresh water, copper, lithium, titanium, and other minerals. Even farmland is affected because with higher population, more food is required from a similar amount of arable land. Additional-cost efforts such as irrigation can increase food supply from available arable land.

The basic problem is two-fold: rising population takes place while the easiest to extract resources are depleting. The result seems to be Limits to Growth, as modeled in the 1972 book, “The Limits to Growth.” Academic research shows that problems such as those modeled (sometimes referred to as “overshoot and collapse”) have been extremely common throughout history.

Precisely how this problem unfolds varies according to the specifics of each situation. Growing debt levels and increasing wage disparity are common symptoms before collapse. Governments become vulnerable to losses in war and to being overthrown from within. Epidemics tend to spread easily because high wage disparity leads to poor nutrition for many low-wage workers. Dr. Joseph Tainter, in his book, “The Collapse of Complex Societies,” describes the situation as the loss of complexity, as a society no longer has the ability to support some of the programs it previously was able to support.

At the same time the existing economy is failing, the beginnings of new economies can be expected to start. In some sense, economies “evolve,” just as plants and animals evolve. New economies will eventually replace existing ones. These changes are a necessary part of evolution, caused by the physics of the biosphere.

In physics terms, economies are dissipative structures, just as plants, animals, and hurricanes are dissipative structures. All dissipative structures require energy supplies of some type(s) to grow and remain away from a dead state. These structures do not “live” endlessly. Instead, they come to an end and are often replaced by new, slightly different, dissipative structures.

[2] Over the next 10 years, the general direction of the economy will be toward contraction, rather than growth.There are many indications that the world economy is hitting a turning point because of rising population and diminishing returns with respect to resource extraction. For example:

[a] Debt levels are very high in the US and other countries. A rising debt level can temporarily be used to pull an economy forward without adequate energy supplies because it indirectly gives workers and businesses more spendable income. This income can be used to work around the lack of inexpensive energy products of the preferred types in a variety of different ways:

- It can allow consumers to afford a higher price for existing energy products, if the additional funds get back to customers as higher incomes or lower taxes.

- It can allow businesses to find more efficient ways of using resources, such as ramping up international trade or building more efficient vehicles.

- It can allow the development of new energy products, such as nuclear power generation and electricity from wind and solar.

What we are finding now is that these new approaches tend to encounter bottlenecks of their own. For example, oil supply is sufficiently constrained that the current level of international trade no longer seems to be feasible. Also, wind and solar don’t directly replace oil; electricity based on wind turbines and solar panels can lead to blackouts. Furthermore, diminishing returns with respect to oil and other resources tends to get worse over time, leading to a need for ever more workarounds.

If at some point, extraction becomes more constrained and workarounds fail to provide adequate relief, added debt will lead to inflation rather than to hoped-for economic growth. Higher inflation is the issue that many advanced economies have been struggling with recently. This is an indication that the world has hit limits to growth.

[b] Because of low oil prices, companies are deciding to cut back new investments in extracting oil from shale, and likely elsewhere.

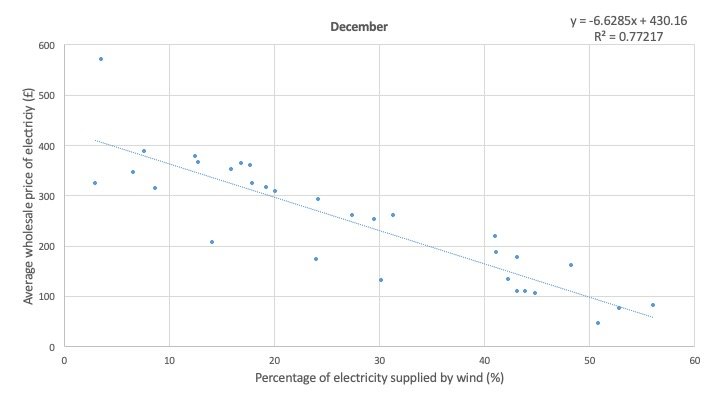

Figure 1. Brent equivalent oil prices, in 2024 US dollars, based on a combination of indications through 2023. Sources include historical oil prices in 2023$ from the 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the Energy Institute; the increase in average Brent spot price from 2023 to 2024, published by the US EIA; and the US Consumer Price Index for Urban consumers.

Figure 1. Brent equivalent oil prices, in 2024 US dollars, based on a combination of indications through 2023. Sources include historical oil prices in 2023$ from the 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the Energy Institute; the increase in average Brent spot price from 2023 to 2024, published by the US EIA; and the US Consumer Price Index for Urban consumers.

Figure 1 shows that oil prices rise and fall; they don’t rise endlessly. They rose after US oil production hit its first limits in 1970, but this was worked around by ramping up oil production elsewhere. Prices rose in the 2003 to 2008 period and then fell temporarily due to recession. They returned to a higher level in 2011 to 2013, but they have settled at a lower level since then.

One factor in the price decline since 2013 has been the production of US shale oil, adding to world oil supply. Another factor has been growing wage disparity, as workers from rich countries have indirectly begun to compete with workers from low-wage countries for many types of jobs. Low-wage workers cannot afford cars, motorcycles, or long-distance vacations, and this affordability issue is holding down oil demand.

US oil production from shale is in danger of collapsing during the next few years because prices are low, making new investment unprofitable for many producers. In fact, current prices for oil from shale are lower than shown on Figure 1, partly because US prices are a little lower than Brent, and partly because prices have fallen further in 2025. The recent price available for US WTI oil is only about $62 per barrel.

[c] World per capita coal production has fallen since 2014. A recent problem has been low prices.

Figure 2. World coal production through 2023 based on data of the 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the Energy Institute.

Figure 2. World coal production through 2023 based on data of the 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy, published by the Energy Institute.

Transportation costs are a major factor in the delivered price of coal. The reduced production of coal is at least partly the result of coal mines near population centers getting mined out, and the high cost of transporting coal from more distant mines. Today’s coal prices do not seem to be high enough to accommodate the higher costs relating to diminishing returns.

[d] In theory, added debt could be used to prop up oil and coal prices, but debt levels are already very high.

Besides the problem with inflation, mentioned in point [a], there are problems with debt levels becoming unmanageably high.

Figure 3. Figure from page 10 of The Long-Term Budget Outlook 2025 to 2055, published in March 2025 by the US Congressional Budget Office.

Figure 3. Figure from page 10 of The Long-Term Budget Outlook 2025 to 2055, published in March 2025 by the US Congressional Budget Office.

Figure 3 shows US government debt as a ratio to GDP. If we look at the period since 2008, there was an especially large increase in debt at the time of the 2007-2009 Financial Crisis and the 2020 Pandemic. The debt level has become so high that interest on the debt is likely to require tax revenue to rise endlessly. The underlying problem is needing to pay interest on the huge amount of outstanding debt.

Putting together [a], [b], [c], and [d], the world has a huge problem. As the world economy is currently organized, it is heavily dependent on both oil and coal. Oil is heavily used in agriculture and in transportation of all kinds (cars, trucks, trains, airplanes, and ships). Coal is especially used in steel and concrete making, and in metal refining. We don’t have direct replacements for coal and oil for these uses. Wind and solar are terribly deficient at their current state of development.

The laws of physics tell us that, given the world’s current infrastructure, a reduction in the availability of both crude oil and coal will lead to cutbacks in the production of many kinds of goods and services around the world. Thus, we should expect that GDP will contract, perhaps for a long period, until workarounds for our difficulties can be developed. Today’s wind turbines and solar panels cannot solve the problem for many reasons, one of which is that fact that production and transport of these devices is dependent upon coal and oil supplies.

Thus, without adequate oil and coal to meet the needs of the world’s growing population, the world economy is being forced to gradually contract.

[3] Overall living standards can be expected to fall rather than rise during the next decade.A recent article in the Economist shows the following chart, based on an analysis by the United Nations:

Figure 4. Chart showing global average “Human Development Index,” as calculated by the United Nations, in the Economist.

Figure 4. Chart showing global average “Human Development Index,” as calculated by the United Nations, in the Economist.

Figure 4 shows the trend in the Human Development Index as level in 2023-24. I expect that the trend will gradually shift downward in 2024-2025 and beyond. Modern advances, such as the availability of potable water in homes and the availability of electricity 24 hours per day, will become increasingly less common.

The Economist article displaying Figure 4 notes that, so far, most of the drop in living standards has happened in the poorer countries of the world. These countries were hit harder by Covid restrictions than rich countries. For example, the drop in tourism had a greater impact on less advanced countries than on rich countries. Poor countries were also affected by a decline in export orders for luxury clothing.

Outside of poor countries, young people are already finding it difficult to find jobs that pay well. They are often burdened with debt relating to advanced education, making it difficult for them to have the same standard of living that their parents had. This trend is likely to start hitting older citizens, as well. Jobs will be available, but they won’t pay well. This problem will affect both young and old.

[4] Governments will be especially vulnerable to cutbacks.History shows that when overshoot and collapse occur, governments are likely to experience severe difficulties, indirectly because many of their citizens are getting poorer. They require more government programs, but if wages tend to be low, the taxes they pay tend to be low, too.

Unfortunately, the kinds of cutbacks being undertaken by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are very much necessary to get payments by the US government down to a level that can be supported by taxes. Regardless of how successful the current DOGE program is, I expect a huge reduction in the number of individuals on the payroll of the US government, perhaps by 50% to 75%, in the next 10 years. I also expect major cutbacks in the funding for outside organizations, such as universities and the many organizations DOGE has targeted.

At some point, the US government will need to reduce or eliminate many types of benefit payments made now. One approach might be to try to send many kinds of programs, such as job loss protection, Medicaid, and Medicare, back to the states to handle. Of course, the states would also have difficulty paying for these benefits without huge tax increases.

[5] Ten years from now, universities and colleges will enroll far fewer students.I expect that university enrollments will fall by as much as 75% over the next 10 years, partly because government funding for universities is expected to fall. With less funding, tuition and fees are likely to be even higher than they are today. At the same time, jobs for university graduates that pay well will become less available. These considerations will lead fewer students to enroll in four-year programs. Shorter, more targeted education teaching specific skills are likely to become more popular.

There will still be some high-paying jobs available, requiring university degrees. One such area may be in finding answers to our energy and resource problems. Such research will likely be carried out by a smaller number of researchers than are active today because some current areas of research will be discarded as having too little potential benefit relative to the cost involved. Any approach considered will need to succeed with, at most, a tiny amount of government funding.

High paying jobs may also be available to a few students who plan to be the “wheeler-dealers” of the world. Some of these wheeler-dealer types will want to be the ones founding companies. Others will want to run for public office. They may be able to succeed, as well. They may want to study specialized tracks to advance their career goals. Or they may want to choose institutions where they can make contacts with people who can help them in pursuing their career goals.

For most young people, I expect that four-year university degrees will increasingly be viewed as a waste of time and money.

[6] In a shrinking economy, debt defaults will become an increasing problem.A growing economy is very helpful in allowing financial institutions to prosper. With growth, future earnings of businesses tend to be higher than past earnings. These higher earnings make it possible repay both the borrowed amount and the required interest. With growth, there is little need to lay off employees. Thus, the employees have a reasonable chance to repay mortgage loans and car loans according to agreed-upon terms.

If an economy is shrinking, overhead becomes an ever-larger share of total revenues. This makes profits harder to achieve and may make it necessary to lay off employees. These laid-off employees are more likely to default on their outstanding loans. As debt defaults rise, interest rates charged by lenders tend to rise to compensate for the greater default risk. The higher interest rates make debt repayment for future borrowers even more difficult.

All these issues are likely to lead to financial crises, as debt defaults become more common.

[7] As debt defaults rise, banks tend to fail. This can lead to hyperinflation or deflation.In a shrinking economy, the big question when banks fail is, “Will governments bail out the banks?”

If governments bail out the failing banks, there is a tendency toward inflation because the bailouts increase the money supply available to citizens, but not the quantity of goods available for purchase. If enough banks fail, the tendency may be toward hyperinflation–way too much money available to purchase very few goods and services.

If no government bailouts are available, the tendency is toward deflation. Without bailouts, the problem is that fewer banks are available to lend to citizens and businesses. As a result, fewer people can afford to buy homes and vehicles using debt, and fewer businesses can take out loans to purchase needed supplies. These changes lead to less demand for finished goods. This change in demand can indirectly be expected to affect commodity prices, as well, including oil prices. With low prices, some suppliers may go out of business, making any supply problem worse.

Regardless of whether bailouts are attempted or not, on average, citizens can be expected to be getting poorer and poorer as time goes on. This occurs because with a shrinking economy, fewer goods and services will be made. Unless the population shrinks at the same rate, individual citizens will find themselves getting poorer and poorer.

[8] Expect more tariffs and more conflicts among countries.Without enough oil for transportation, the quantity of imported goods must be cut back. A tariff is a good way of doing this. If one country starts raising tariffs, the temptation is for other countries to raise tariffs in return. Thus, the overall level of tariffs can be expected to rise in future years.

Without enough goods and services for everyone to maintain their current standard of living, there will be a definite tendency for more conflict to occur. However, I doubt that the result will be World War III. For one thing, the West seems to have inadequate ammunition to fight a full-scale conventional war. For another, the nuclear bombs that are available are valuable for providing fuel for our nuclear power plants. It makes no sense to use them in war.

[9] Expect an increasing share of empty shelves, as time goes on.High tech goods are especially likely to disappear from shelves. Replacement parts for automobiles may also be difficult to find, especially before an aftermarket of locally manufactured parts appears.

[10] Interest rates are likely to stay at their current level or increase to a higher level.The high level of borrowing by governments and others makes lenders reluctant to lend unless the interest rates are high. It should also be noted that current interest rates are not high relative to historical standards. The world has been spoiled in recent years with artificially low interest rates, made possible by Quantitative Easing and other manipulations.

[11] Clearly, this list is not exhaustive.The world economy has gone through two major disruptions in recent years, one in 2008, and one in 2020. Very unusual changes such as these are quite possible again.

We don’t know how soon new economies will begin to evolve. Eric Chaisson, a physicist who has researched this issue, says that there is a tendency for ever more complex, energy-dense systems to evolve over time. This would suggest that an even more advanced economy may be possible in the future.

Note: I am also publishing this post on Substack. At this point, it is still sort of an experiment. Comments sometimes don’t post well on WordPress. This will give readers a different option for viewing posts. Using Substack, my posts may reach a new audience as well.

Some of you may receive an email about my Substack post. I put in some email addresses back in January 2024 when I put up a post on Substack earlier. Subscriptions will continue to be free both places. This is a direct link to my new post. https://gailtverberg.substack.com/p/economic-contraction-coming-right

If the government achieves its targets for renewable electricity capacity for 2030, will it meet its objective for virtually decarbonising the GB grid? Other calculations are more optimistic but this note suggests that in all probability the answer is no.

I looked at the last year (May 2025 to end April 2025) and multiplied the output of solar and wind generators in each half hour period to reflect the proposed increase in capacity and possible improvements in yield per megawatt of capacity. I also amended the output of nuclear power stations to reflect the closure of two units and I added the possible ouput of NZT, the proposed new gas fired power station with carbon capture.[1] In addition, I assume a 10% increase in total electricity demand resulting from the use of EVs and heat pumps.

This analysis shows that solar, wind, nuclear and hydro would cover about 90% of total GB electricity demand in 2030 if the weather patterns were the same as in the last 12 months. The government could not meet its target to make as much clean electricity as the grid uses over the course of a year even if we add in biomass generation as a 'clean' source.[2]

Absent the rapid growth of either hydrogen or gas power stations with CCS, we will also struggle to reach the second target of getting 95% of total electricity generation from clear sources. Put simply, clean energy is too variable to mean that 95% of generation will come from wind and other low carbon routes, even using the enhanced capacity of import interconnectors. At times of prolonged low wind, fossil electricity sources will often be needed throughout the year.

Achieving targets for 2030 generation.

The UK plans to increase its renewable energy capacity substantially by 2030. The plan is that 'clean sources produce as much power as Great Britain consumes in total' by this date. As a second objective, the government says, 95% of all generation should come from clean sources.[3]

In the basic analysis below, I suggest that neither target can be achieved unless wind and solar capacity is increased even more ambitiously than currently planned. Or that both of the Hinkley Point C reactors come online by 2030. At the moment EdF is expecting Hinkley Point C to start between 2029 and 2031.

I looked at half hour by half hour electricity generation data for the 12 month period from May 1st 2024 to April 30th 2025. I used data provided by NESO, the GB electricity system operator, to model what might happen in 2030 if the same meteorological conditions pertain.

NESO provides accurate estimates of the amount of electricity provided by the main sources of power for each thirty minute period. These sources include gas turbines, nuclear power stations, hydro-electric, solar, wind, biomass and other generators such as energy from waste plants.[4]

I assume that by 2030 the UK had reached the midpoint of the government's targets. This means

o 46 gigawatts of solar, up from about 17.6 gigawatts in the year studied[5]

o 28 gigawatts of onshore wind, up from about 15.7 gigawatts in the year studied

o 46.5 gigawatts of offshore wind, up from about 15.0 gigawatts in the year studied

I multiplied the output of onshore wind, offshore wind and solar for each half hour in the year to the end of April 2025 by the targeted change in generating capacity. So, for example, if solar power delivered 1 gigawatt in a particular half hour period in this year I calculate that it would provide 2.6 gigawatts in 2030. 46 gigawatts of solar capacity in 2030 will provide 2.6 times as much electricity as 17.6 gigawatts does today.

I took note of EdF's current intention to close two nuclear reactors in 2027. Hartlepool and Heysham 1 power stations have a maximum capacity of around 1,170 MW each. This leaves three reactors open in 2030: Sizewell B, Torness and Heysham 2 (although Torness and Heysham 2 are said to be closing during the course of 2030). I have optimistically forecast that nuclear power output will decline to about 60% of today's levels in 2030, equivalent to a yearly average of around 3 GW of working capacity after allowing for outages and refuelling. I assume Hinkley Point C has not opened by 2030.

Over the 17,520 half hour periods of the year, output from wind and solar varies hugely. The highest wind output during the year was over a hundred times greater than the calmest period. These two events, over 22 gigawatts on 17th December 2024 and 0.2 gigawatts on 22nd January were just over a month apart. Of course these large differences will remain if we model an alternative world in which wind and solar capacities are much greater.

The results of the analysis

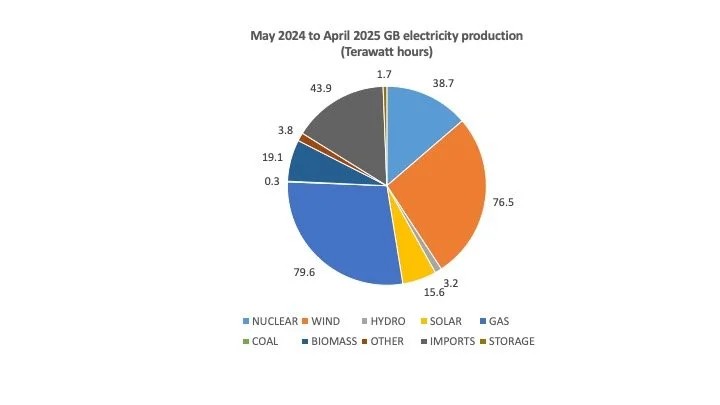

In the year under study to the end of April 2025, sources defined as 'clean' provided just under 48% of GB electricity supply.[6] These generating stations produced 134 terawatt hours out of a total of 282.5 terawatt hours consumed in GB.

The government targets an increase in solar power capacity from an average of about 17.6 gigawatts in the year studied to about 46 gigawatts in 2030.[7] This is a multiple of 2.6 times. Onshore wind is planned to go up from 15.7 to 28 gigawatts and onshore wind from 15.0 gigawatts to 46.5 gigawatts. NESO half hourly data does not separate onshore and offshore outputs so I have generated estimates of capacity factors from each source from information published elsewhere. The result is that expected output from wind will rise by about 2.55 times if new connections match the government's target.

a. The basic test

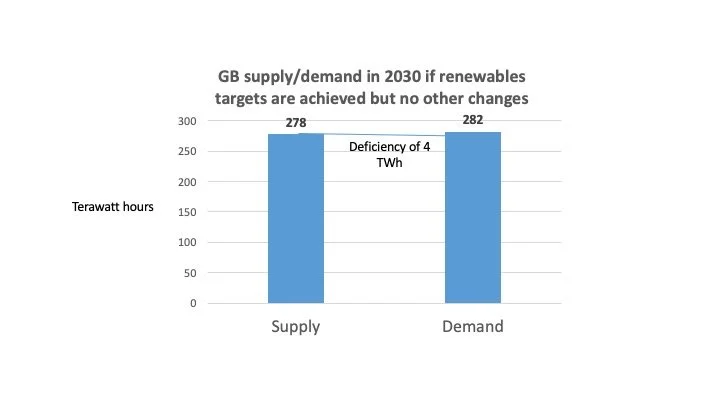

Multiplying the power output from wind and solar in the 20224/2025 years as if the target 2030 capacities were already in use increases the amount of clean electricity produced to 278 terawatt hours.[8] Total electricity demand in the year under study was 282 terawatt hours.

Production of clean energy - 278 terawatt hours

Less Energy consumption - 282 terawatt hours

Surplus or deficit production - minus 4 terawatt hours

b. Increasing realism

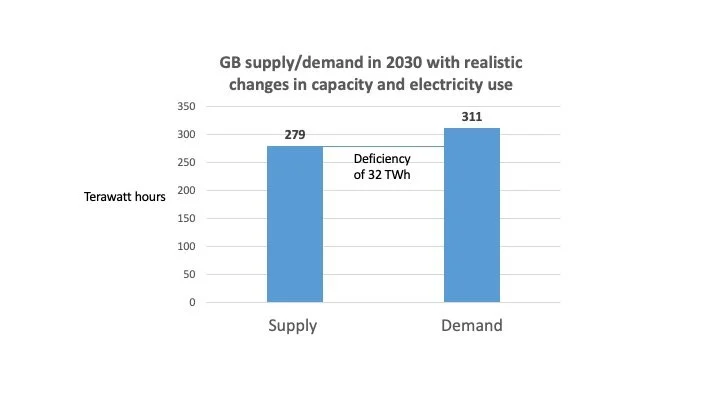

Electricity production, after having falling regularly for several decades, will start increasing as EVs become more common, heat pumps gain in popularity and data centre use ramps up. So I increased total electricity consumption by 10% across all half hours in 2030.

The average output per megawatt of capacity from wind and solar power will also probably rise. Locations will be better chosen and technologies will improve. I propose a 4% increment in electricity production per unit of solar and wind power capacity in 2030. But nuclear production will fall as two nuclear plants are withdrawn from service in 2027, cutting average production by 40%. (I assume Hinkley Point C has not opened by 2030, an assumption which may be too harsh).

In addition, GB will probably have its first carbon capture and storage gas-fired power station by 2030 and I include an estimate of maximum output from this unit.

The impacts of these changes are as follows

Production of clean energy - 279 terawatt hours

Less Energy consumption - 311 terawatt hours

Surplus or deficit production - minus 32 terawatt hours

So under reasonable assumptions GB's output of clean electricity will be only about 90% of the possible higher level of demand in 2030. Adding in biomass-based electricity production will not be sufficient to fill this gap, largely because of the much more limited subsidy available to Drax by 2030 and the restrictions placed on how much electricity is generated.

c. The government's second objective - 95% of all production is clean

Why is the objective even more difficult to achieve? At those moments when wind and solar plus other clean sources are not sufficient to cover that hour's demand, other sources will have to be brought into action. These may include more gas with CCS or hydrogen turbines but these source are unlikely to be operating at a large scale by 2030. The more variable is wind and solar output, the more other generators will have to be used, pushing down the percentage of clean production. This does not seem to be properly acknowledged in official communications.

In the 12 months of study, under the realistic assumptions including the 10% increase in demand and a 4% rise in wind and solar efficiency, GB would see about 6,400 half hour periods of excess production and about 11,100 half hours of deficiency. (This is before any biomass use is taken into account).

The excess production periods total 32 terawatt hours and deficiencies amount to about 71 terawatt hours. If the new gas with CCS power station operates during all the 11,100 half hours of deficiency, the volume of unfilled power need would fall to 66 terawatt hours when alternative generators or imports would have to be pulled into use. These numbers are in the context of total expected electricity usage of 311 terawatt hours so the UK would be unlikely to be able to make more than 80% of its electricity from clean domestic sources over the course of year.

Imports will help but even if clean imported electricity are available, the core problem is that periods of deficiency require more import connectors than are available. NESO predicts about 12 gigawatts of capacity by 2030, of which about 1 gigawatt represents the links to the island of Ireland and which are generally used to export from Great Britain, not import.[9]

Well over 25% of all half hour periods during the year under study experienced deficits of more than 11 gigawatts. Even in the highly unlikely event that all 11 gigawatts of import capacity were available at all these times, about 22 terawatt hours of demand would remain unsupplied. Other sources of electricity would have to be employed. At the improbable best, therefore, the UK could only hope to provide 94% of generation from clean sources, and this is assuming imports are all 'clean'.

d. What about the impact of storage, such as using batteries?

The problem with using storage is that the demands for extra electricity, or alternatively the need to take in surplus power, typically cannot be met by the volumes of batteries proposed. If clean supplies are short and they persist for several days, batteries are almost useless. Long duration storage is needed rather than batteries, which are more capable of dealing with short term fluctuations in power supplies.

One particularly clear period under study was January 8 to January 11, when clean power, including gas with carbon capture, and 11 gigawatts of imports still left GB short of 1 terrawatt hour of power over a period of less than 3 days. The average deficiency during this period was about 15 gigawatts. NESO is estimating that GB will have a total storage capacity of about 50-99 gigawatt hours by 2030. So, at the very best, GB might have battery and pumped hydro storage of about 6 hours during a similar 65 hour period on 2030. The excess of demand over supply did not stop on January 11th. It went on for 360 hours in total up until 23rd January so batteries and other storage might have meet less than 2% of the eventual need.

What about periods of excess supply? The best days in the GB market were a month earlier from December 14th to December 24th. The average excess supply in this period was about 16 gigawatts, equating to about 6 hours of storage capacity rather than the 240 hours for which batteries would have been required to capture the excess. And even if other countries had wanted all that electricity, our export capacity would be routinely exceeded. The excess power would inevitably have been wasted.

Conclusions

GB will not attain clean power output levels equal its electricity demand in 2030. Assuming reasonable growth in electricity demand, improvements in solar and wind plus a more than 2.5 times volume of renewables capacity and a new CCS gas power station but declining nuclear output, clean power will only represent about 90% of national need.

The second target - ensuring that 95% of all generation will be clean - will not be met either. This is principally because when wind output is low the expected level of interconnection with Europe will not provide sufficient power to meet requirements. Even if 11 gigawatts of connectors are available, imports will frequently not fill the deficiency. So non-clean sources in GB, such as gas without CCS, will need to be utilised to match demand and supply.

Batteries are not particularly useful in helping to maximise the amount of clean power generation. Spells of low wind speed and little sun last far too long for storage systems to offer substantial aid, even if battery capacity rises as fast as expected.

To achieve its targets GB needs even more renewable capacity and an ability to turn surplus power into usable hydrogen that can be used to make electricity when supplies are tight.

[1] In reality, NZT may not operate much of the time because of low prices resulting from Europe-wide power surpluses at times of high wind speeds.

[2] However 2025 announcements of subsidy levels suggest that biomass will only probably produce about half as much electricity in 2030 as today.

[3] The Northern Irish electricity system is part of the all-Ireland network, separate from the GB system. The government's targets refer to the GB network.

[4] The last coal-fired power station in GB closed during the twelve month period and is therefore included for part of the year.

[5] The figures used for the year under study are approximate average capacities across the 12 month period.

[6] Clean sources are defined as nuclear, wind, solar and hydro.

[7] The government offers a range for wind and solar capacity targets in 2030. I have chosen the mid point of this range.

[8] Wind, solar, nuclear and hydro.

[9] https://www.neso.energy/document/346651/download

Abstract

This article takes data surrounding last week's announcement of the first SMR farm in Ontario, Canada to assess whether this new approach to nuclear shows any signs of reducing costs below the level of larger reactors and renewable generators. In brief, the conclusion is that it does not.

SMRs

A small number of experimental SMRs have been built or are under construction in Russia, China and Argentina.[1] The history of these reactors has been full of delays and huge cost overruns.

Nevertheless recent months and years have seen an explosion of interest in constructing new reactors, often to serve specific customers with a high and consistent power need such as the operation of data centres. The International Atomic Energy Agency reported that there are 80 different designs and design concepts for new types of SMRs around the world although no formal decisions had then been taken to proceed with any new projects. Many commentators see SMRs as a realistic route to decarbonising electricity production; in its recent report, the UK's Tony Blair Institute wrote that 'The new generation of small modular reactors offers hope for the renaissance of nuclear power'.[2]

We saw a big step forward last week with the final governmental approval given for the construction of the first SMR farm at an existing nuclear reactor site in Ontario, Canada. The information released when the announcement was made gives us useful information about the possible cost of SMRs. Despite the upbeat press releases from participants in the project, the numbers provided will not increase optimism about the future of this route to a zero carbon energy system.[3]

The plans

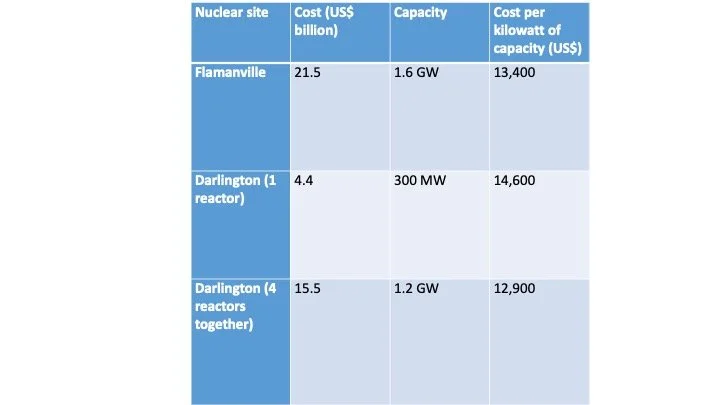

The Darlington project plans to eventually put 4 SMRs, each of 300 MW capacity, onto the site. The Ontario government estimates the project's total cost at 20.9 billion Canadian dollars (CAN$) and is supporting it financially. Expressed in US dollars, the price is about $15bn at early May 2025 exchange rates for a total of 1.2 gigawatts of electricity.

The technology provider is GE Hitachi using its BWRX 300 boiling water reactor, a simplified version of the company's full scale nuclear plants. The BWRX 300 has been identified as one of the lowest cost competitors in the race to dominate the SMR industry and the design is one of those currently being evaluated in the UK as a potential recipient of substantial government support. GE Hitachi claims numerous advantages over other SMR technologies, including lower steel and concrete costs, passive cooling and the use of well-understood and widely available nuclear fuel.

Groundwork has been underway for more than 2 years near the existing Darlington nuclear power station in readiness for the formal safety approval finally given in April 2025. Construction is projected to be completed in 2030.[4] In a challenge to the widespread view that SMRs will be simple to construct, one of the challenges facing the first Darlington reactor is creating a tunnel to carry cooling water that will stretch for 3.4 kilometres with a diameter of 6 metres.[5]

The costs of building and operating the SMRs in Ontario.

Capital cost

The first reactor to be built is projected to have a cost of 6.1bn CAN$ (about US$4.4bn). Additional infrastructure will be needed at the site that will be shared between this SMR and the three equivalents that will be eventually built there. The capital cost of these shared facilities is separately budgeted at 1.6bn CAN$ (about US$1.15bn).

The total budget for the entire 4 reactor site is 20.9bn CAN$ (about US$15bn). So the three SMRs to be installed after the first reactor are projected to cost a total of about 13.2bn CAN$, or 4.4bn CAN$ each, a roughly 28% reduction on the 'first of a kind' (FOAK).

The cost per kilowatt of capacity for the first reactor (excluding the price of the shared services is about 20,300 CAN$, or US$14,600. Taken together, all four come in at about US$12,900.

Just a year ago, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) published a report on SMRs that showed 2020 forecast for a kilowatt of capacity for a BWRX 300 of just under US$2,900 for an 'nth of a kind' reactor.[6][7] This number was expressed in 2023 dollars to account for inflation. The suggested cost of the first Darlington, Ontario reactor is thus about five times the projected NOAK cost in 2020, just five years ago. (However this comparison could be considered unfair to the GE Hitachi reactor because it compares NOAK and FOAK budgets).

The IEEFA report also provides high and low cost estimates from 2023 for the BWRX 300 reactor from external sources. The low figure is just over US$7,400 and the high number is around US$12,350. Thus the Ontario cost for the first of the four reactors is almost 19% above the 'high' estimate from just two years ago and almost double the 'low' forecast.

As an aside, GE Hitachi in 2020 was estimating its reactor could be constructed in 24-36 months. The building work at the Darlington site commenced in autumn 2022 and is projected to finish in 2030, and therefore is scheduled to take at least 7 years.

Costs compared to renewables

How do the costs per kilowatt of capacity compare to solar and wind equivalents? The Ontario government says that it estimates that the 1.2 GW to be eventually provided in SMR capacity could be replaced by about 8.9 GW of solar and wind power. As far as I can see, it has not split this number between the two renewable sources of electricity.

In the UK, and using capacity factors appropriate to southern England, it would take about 10 GW of solar farms to create an equivalent amount of annual electricity to 1.2 GW of nuclear.[8] Given that Darlington, Ontario sits at a latitude of about 43 degrees north - equivalent approximately to Marseille - compared to London, England at 51 degrees average solar productivity will be probably be higher at the Canadian location.

So let's assume that 8.9 GW of solar PV in Ontario would provide the same amount of power as the Darlington reactors. This would cost no more than about US$9bn in the UK today, and probably much less by the time the reactors are constructed. In other words, solar alone would be less than half the capital cost of the four SMRs to provide the same amount of electricity. (However the province of Ontario does make the valid point that solar PV would probably require far more new grid capacity. It would also need long term storage). But the conclusion has to be that SMRs, at least as shown by the GE Hitachi prices, are not likely to be cheaper to construct than solar or wind.

Comparison with other nuclear sources

Equally important, are SMRs going to be cheaper than full-scale large nuclear reactors?

The new European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) at Flamanville on the Normandy coast of France was connected to the grid in late 2024. The estimated cost of this reactor is about €19.1 billion, or about US$21.5 million.[9] At maximum capacity it produces just over 1.6 gigawatts of electricity, compared to the 1.2 GW projected for the four SMRs at Darlington, Ontario.

Thus the hugely expensive and long-delayed reactor at Flamanville, the fourth EPR to be completed in the world, was cheaper to construct than the estimates for the first SMR at Darlington and only marginally more expensive than the projected costs for the eventual group of 4 reactors when expressed as capital cost per kilowatt of capacity.

Do SMRs offer savings in operating costs over large nuclear power stations and renewable plants?

Most sources suggest that SMRs will have operating costs at roughly the same level as large nuclear plants per unit of capacity. However we cannot know this with any more certainty than the comparison of capital costs.

One careful piece of academic research put it as follows: ..it is expected that O&M and fuelling costs will be very similar to that of LRs.[10] This conclusion was reached some years ago and estimates may now be out of date. However I have seen no data suggesting that SMRs will be cheaper to operate than larger nuclear power plants.

The operating costs include nuclear fuel, which needs to be regularly but infrequently fed into the reactor. At current uranium prices, fuel is unlikely to be a significant portion of total costs.

More important is the cost of staff and here the limited evidence is that SMRs will require more people than larger reactors. Ontario predicts that 2,500 people will work on the SMRs at the Darlington site when the 4 reactors are complete. By comparison, Sizewell B, an existing nuclear power station in the UK, employs about 900 workers and has approximately the same annual output as the 4 reactor Canadian site will have.[11]

However if we optimistically assume that the SMRs will cost the same to run as larger nuclear sites how will they compare with solar? The US Energy Information Agency writes that the cost of running a nuclear power plant is around $22 per megawatt hour of output, or 2.2 cents per kilowatt hour. Fuel is about 0.61 cents per kilowatt hour with operations at around 0.95 cents and maintenance at 0.64 cents.

Most estimates for the operating costs of full-size solar parks are around US$15 per kilowatt of capacity per year. A solar park in Ontario is likely to produce at least 900 kWh per kilowatt annually, implying a cost of around 1.67 cents per kilowatt hour for total operating costs. The conclusion has to be that SMRs are therefore very unlikely to be cheaper to run than large solar farms in the same area as the new nuclear site.

Summary

The data provided by the press releases announcing the world's first new generation SMR park give us some information about costs. Of course we cannot know whether these estimates will be correct. But If they are actually achieved, SMRs will be only marginally cheaper than the current generation of large nuclear power stations. Operating costs will be similar to their larger cousins but possibly much more.

Solar and wind parks are likely to be less expensive in both capital and operating terms. Capital costs for solar may be no more than half the figure for the Darlington project and operating costs around three quarters of the level of SMRs.

By itself, this information does not imply that the rush towards SMRs is misplaced. They may offer cheaper grid connections and will be better at providing power directly to 24 hour electricity customers. But the arguments advanced by commentators such as the Tony Blair Institute need to adjusted recognise that there is no evidence today that SMRs will reduce electricity costs compared to continuing rapid investment in wind and solar.

May 11th 2025

[1] https://www.iaea.org/topics/small-modular-reactors

[2] https://institute.global/insights/climate-and-energy/the-climate-paradox-why-we-need-to-reset-action-on-climate-change

[3] https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1005889/ontario-leads-the-g7-by-building-first-small-modular-reactor

[5] Same as reference 3 above.

[6] https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/SMRs%20Still%20Too%20Expensive%20Too%20Slow%20Too%20Risky_May%202024.pdf

[7] The 2020 figure appears to have been derived from this GE Hitachi web page and adjusted for inflation - https://www.gevernova.com/content/dam/gepower-nuclear/global/en_US/documents/product-fact-sheets/GE%20Hitachi_BWRX-300%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

[8] Assuming a capacity factor of 90% for the SMR and 11% for UK solar.

[9] https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2024/05/09/les-derapages-de-l-epr-de-flamanville-en-graphiques-le-cout-multiplie-par-six-la-duree-du-chantier-par-quatre_5480745_4355771.html

[10] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421517300538?fr=RR-2&ref=pdf_download&rr=93da6ca1cd7fe1fc

[11]https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c93qz4dlqlgo#:~:text=Work%20on%20the%20construction%20of,literally%20from%20the%20ground%20up%22.

Last week the UK government effectively nationalised the blast furnaces at Scunthorpe on the north-east coast of England. These furnaces are the last sites in the UK that can manufacture iron from ore as a precursor to the production of virgin steel. The emergency legislation will help to keep open this important source of local employment and industrial activity.

Nevertheless, I argue that it was an expensive and unnecessary move. Instead of making new virgin steel, the UK should concentrate on recycling the large amounts of old scrap steel that are exported from this country for reprocessing around the world. The owners of Scunthorpe already have plans to switch to using steel using electricity and scrap. Of critical importance to any plan, the price of electricity used for electric arc furnaces needs to be roughly the same as in competitor countries, necessitating a substantial subsidy. Without it, UK steel-making cannot hope to be financially self-reliant. Other countries do this and without financial support, the UK cannot hope to be competitive.

Basic numbers

The most recent data from industry body UK Steel gives the following figures for the UK's consumption and production of steel. These figures relate to 2023. In 1970, the peak year for the country's steel production, the number was five times higher.

UK Production of steel - 5.6 million tonnes, of which 4.5 million tonnes came from blast furnaces

UK Demand for steel - 7.6 million tonnes

So about 2m tonnes of steel had to be imported in 2023. This number probably rose in 2024 after the closure of the blast furnaces at Port Talbot but the figures are not publicly available yet.

But at the same time as importing 2m tonnes of finished metal, the UK collected about 10.5 million tonnes of scrap steel, almost three million tonnes more than total steel demand in the country. Some scrap was used in the existing electric arc furnaces here but most was exported; about 8.5m tonnes of scrap was sent abroad for reprocessing elsewhere back into new steel. (Some of this new steel will have eventually come back to the UK). This makes the UK the world's second largest exporter of scrap steel for recycling. Expressed in per capita terms, the country is the top source of used steel.

Put another way, the country's exports of scrap, which can be easily recycled in electric arc furnaces, alone exceeded its total demand for the metal. There is no need for blast furnaces, such as the ones in Scunthorpe, for the UK to build self-sufficiency in steel production. This has been a consistent worry expressed over recent weeks with many expressing a view that the UK needed to retain the capability to make steel from iron ore in blast furnaces. But simply keeping used steel available for recycling in the UK would provide enough of the metal for the country's needs.

It may be worth noting that many other countries restrict or block the export of steel scrap in order to ensure adequate supplies for recycling in local electric arc furnaces.

What is stopping the UK switching from blast furnaces to make the metal, rather than using scrap steel?

· Large electric arc furnaces (EAFs) for recycling steel are expensive to construct. The EAFs to be constructed by Tata Steel at Port Talbot in South Wales are projected to cost around £1.25bn for a projected capacity of 3m tonnes a year (or potentially around 40% of the UK's total steel needs). The government has committed £500m to assist the transition there from blast furnaces to EAFs.

British Steel (owned by Jingye of China) has stated that the cost of creating two new EAFs on the north east coast will also be about £1.25 billion. The projected total capacity doesn't appear to have been published but based on the Tata numbers we can perhaps assume a similar figure of about 3m tonnes a year.

· UK electricity costs are higher than nearby countries. Even after the government intervention to reduce the costs of electricity transmission to steelworks, one recent study suggests that the British steel industry pays £66 a megawatt hour (MWh) compared to £50 in Germany and £43 in France.[1] Because electric arc furnaces use about 0.5 MWh per tonne of steel output, these higher costs can mean a handicap of £11.50 a tonne of steel from an EAF. At current finished steel prices of around £500 a tonne ($660), this imposes a burden of over 2%. In a low margin industry such as steelmaking, this difference is significant.

· Falling UK demand for steel has imposed an additional weight on investment enthusiasm. Investing £1.25bn in a shrinking market looks a dangerous decision to take. On the other hand, some demand increases are likely in future; wind turbine columns alone might add 1m tonnes a year to UK needs.

· EAFs need far fewer employees per tonne of output, making it politically difficult to allow the closure of a major source of local employment in Scunthorpe. And any new EAFs in that part of the UK will take several years before they begin to hire permanent staff.

The advantages of using EAFs rather than keeping the Scunthorpe blast furnaces open

· EAFs use local scrap metal, reducing the amount exported.

· The UK scrap also contains other metals, such as copper, increasing its value and reducing the need to import materials.

· EAFs produce much less local air pollution than the older steel-making method.

· The carbon footprint of EAFs is about one sixth of steel originating in blast furnaces. The figures will depend on the fossil fuel intensity of the electricity used but most sources estimate a footprint of about 0.35 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel, compared to about 2 tonnes from the blast furnace route. Replacing the 2023 4.5 million tonnes of steel with EAF output would save about 7.4 million tonnes of CO2 or just under 2% of UK emissions.

· Potentially the economics of using scrap could be better. The open market scrap price is around $350 per tonne, equivalent to £263 today, or just over half the value of a tonne of steel in the UK. The price of raw materials is likely to be more stable, avoiding the need to have to buy much coking coal and iron ore on international markets.[2]

· EAFs can help stabilise the electricity market, using power mostly at times when the wind is blowing and not at times of scarcity. Unlike blast furnaces, EAFs can decide when to operate. While not a trivial exercise, steel-making can adjust its demand to match national supplies of electricity.

In summary, both industrial strategy and carbon reduction aims should push us towards EAFs rather than keeping open the Scunthorpe blast furnaces. It makes very little sense to spend large sums keeping the furnaces open rather than sponsoring the building of new EAFs when the UK has such abundant supplies of metal for recycling and the carbon footprint benefits may be equal to at least one per cent of the UK emissions. This is not to dismiss the profound social consequences of the reduced employment prospects for steelworkers in the Scunthorpe area.

[1] https://www.uksteel.org/electricity-prices

[2] EAFs use some iron ore and some coal but in much smaller quantities than blast furnaces.

On 10th December of last year the UK government announced it had signed contracts for the support of the first two parts of the proposed carbon capture cluster in the north-east of England.[1] The projects to be funded are a new gas-fired power station with CCS, largely owned by BP, and a CO2 transmission network that takes the gas to subsurface storage in the North Sea. BP is also a major shareholder in this planned network. Two days later, the senior civil servant in DESNZ, the department responsible for developing the UK's carbon capture capability, said that the details of the deals would be published 'soon'.[2] He made this comment under questioning from a committee of the UK parliament.

When is 'soon'? On 7th February, almost two months later, I wrote to DESNZ to ask if the terms of the contracts had been put into the public domain. The response came back rapidly; the department says that they will be published 'in due course', with no mention of any specific date.[3] It looks as though we may have to wait a long time to see the details of the schemes, including both the payments that will be made to the power station for capturing the CO2 and the pipeline network for transporting it. At the moment nobody has any idea how much these projects will cost energy bill payers and taxpayers.

Does this matter? Yes: the prospective subsidy for the UK's CCS schemes is now set at almost £22bn and these first examples will set the cost expectations for all future developments. This note briefly looks at the what financial support is likely to have been agreed.

In summary, the subsidy agreed may be equivalent to doubling the cost of generating electricity in a gas-fired power station. The cost of gas with CCS could therefore be three times the price of electricity from a solar farm.

Background: the CCS projects.

The government has approved in principal two 'clusters' for CCS. One is on the north-east coast of England and the other on north-western side, spreading out into North Wales. Industries producing CO2 can apply for subsidies to collect and store the gas. The first contracts to be signed are for two projects in the north-east cluster: a new gas-fired power station and a separate transmission and storage network that takes the CO2 from the power station and future other sites.

· Net Zero Teesside Power (NZT Power)

The proposed power station will be located close to the mouth of the Tees estuary. The storage pipeline, engineered to offer a maximum of 4 million tonnes a year, will go offshore immediately to the depleted Endurance saline aquifer for permanent storage.

The design is for a 742 MW power station. If it operates all the time it will produce about 2.2 million tonnes of CO2 per year, and this figure is stated as the storage target. However more realistic expectations seem to be that the actual amount to be sequestered will be around 1 million tonnes. This suggests that the plant is expected to be operating about 50% of the time, generating an average of about 1-1.5% of current UK electricity needs.

The new power station will use a carbon capture technology in Shell's portfolio. Called CANSOLV, it operates at two existing power stations that use carbon capture. These two plants both burn coal as their fuel. No gas-fired power station uses CANSOLV and indeed NZT will probably be the first such plant worldwide to capture its emissions.

NZT Power is a joint venture between fossil fuel producers BP and Equinor. Construction will start in 2025 and is intended to be complete by 2028.

· Northern Endurance Partnership (NEP)

The transmission and storage network is owned by a consortium of BP, Equinor and TotalEnergies. The pipeline operated by NEP will run across the north east of England, passing close to some of the businesses that are applying for carbon capture subsidy. These entities include two blue hydrogen production plants as well as NZT.

The CO2 will be sent via a 145 km pipeline to permanent storage in the North Sea. The NEP has chosen the Endurance saline aquifer about 1000 metres below the surface.

· Types of remuneration agreed by government

We don't yet know the numbers attached to the subsidies but we have been told the bases for payment.

The transmission and storage network will be allowed to charge a price for each tonne of CO2 stored. It will also benefit from payments for lack of use of its network. In other words, should the early CO2 production projects not start immediately the network is ready, NEP will be paid a fee for under-use. In addition, government is providing support for the costs of insuring against CO2 leakage. It also promises a payment to compensate NEP when the subsidy scheme has discontinued paying the per tonne of CO2 fee because the maximum financial support has been reached.

The power station has a completely separate payment scheme. This involves two mechanisms; one that pays the plant for being available for low carbon generation, even if no electricity is being produced and a second that makes a payment that is intended to cover the higher costs of operating CCS equipped power station. This variable payment will in effect be a top-up of the wholesale market price and will be calculated daily 'benchmarked against a reference unabated plant'. The intention seems to be to pay awell-defined subsidy for each MWh of electricity produced bringing the CCS-equipped plant to financial equivalence with a similar power station with no CO2 collection.

How much will the CO2 collection and sequestration scheme cost?

The government talks of most of the additional bills being added to domestic and business electricity bills. The rest will be provided by general taxation.

CO2 capture in a power station uses substantial energy. This is used both in the action of catching the CO2 but also to generate the heat that drives off the CO2 from the chemicals that have captured it. In the process planned for NZT, a type of chemical called an amine will capture the gas. The amine is then taken to a chamber where it is heated and the CO2 released so that it can be pipelined to storage.

Very roughly, it will take about 1 MWh of energy (heat and electricity) to capture 1 tonne of CO2 at a gas-fired power station. We don't know the exact quantity because CCS is not yet operating on a full-sized plant.

Estimates of the full cost of carbon capture, including the energy use, range between about £110 per tonne of CO2 and much higher numbers. The £110 figure is taken from a written submission by a group at Oxford University to the UK parliament committee enquiry mentioned in the first paragraph of this note.[4] The researchers write that this is 'the industry's most optimistic full chain cost projection'.

Other recent sources suggest higher figures. One research report suggests the cost may be as much as twice this level.[5]These figures will include a return on the large amounts of capital employed in building the capture facility, not just the operating cost.

A typical modern gas-fired power station produces a tonne of CO2 for each three megawatt hours of electricity output. The implication is therefore that carbon capture from the new NZT plant on the north-east coast will add about £37-£75 per MWh to the cost of electricity produced.

The recent announcement of support for the Drax power station in north-east England gives us some help determining how high this figure is. According to Simon Evans of Carbon Brief, estimates made by the UK government suggests an expectation of average wholesale prices of around £75-80 per MWh in future electricity markets.[6] These figures are before the price of carbon is applied.

Other sources have estimated lower figures for CCS but these earlier figures usually do not take into account recent increases in the expected cost of installing CCS equipment. Nor do they account for the inevitable premium arising from having to capture CO2 from the dilute concentrations in a gas-fired power station exhaust and transporting the gas a long distance to an offshore permanent storage site.

Typically, gas power stations emit an exhaust stream which is only about 3.5% CO2, a number far lower than most chemical processes and also well below the concentrations from a coal-fired power station. Capturing CO2 from a gas-fired power station is the most expensive way of reducing emissions from a static source.

What are the implications for the cost of power from the NZT plant?

Assuming that the proposed NZT power station typically delivers electricity at an average price of £75 per MWh, the CCS will add between about 50% and about 100% to the cost of the power. The total bill to customers will range from about £112 to approximately £150 per MWh.

These figures compared to costs of around £50 for onshore wind and solar.[7] So renewables are less than half the cost of gas with CCS. I am being probably too suspicious but perhaps this is the reason that the subsidy that BP and its partners have been awarded has not been made public.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/contracts-signed-for-uks-first-carbon-capture-projects-in-teesside

[2] https://committees.parliament.uk/work/8576/carbon-capture-usage-and-storage/publications/oral-evidence/

[3] Personal communication from press office at DESNZ.

[4] https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/131665/pdf/

[5] Cost numbers obtained from 'Curb Your Enthusiasm', a report published by Carbon Tracker. https://carbontracker.org/reports/curb-your-enthusiasm/.

[6] Reference price estimate is taken from a BlueSky post by Simon Evans of Carbon Brief at https://bsky.app/profile/drsimevans.carbonbrief.org/post/3lhsuawsv4s26

[7] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6556027d046ed400148b99fe/electricity-generation-costs-2023.pdf. The figures given in this report are in 2021 prices and I have inflated them to current levels.

The purpose of this note is to point out that the CO2 that will need to be captured to make synthetic fuels is only slightly less than the carbon dioxide emitted by burning the equivalent amounts of fossil oil or gas. The crucial implication is that it might make sense not to focus on synthetic alternatives but to develop massive carbon capture infrastructure instead that makes burning fossil fuels carbon neutral. At present prices, it will be far less expensive to burn oil and gas and then collect an equivalent amount of CO2 than it will be to manufacture synthetic fuels. (Many of the numbers in this article are sourced from an industry research paper, referenced at the foot of the page.)

***

Many hard-to-abate sectors, such as aviation and long distance shipping, will continue to need liquid fuels indefinitely. The most commonly accepted route to decarbonisation is to substitute liquid fossil fuels, such as kerosene for aircraft and heavy fuel oil for ships, with synthetic equivalents compounds made from green hydrogen and carbon dioxide. These alternatives can be close to carbon neutral because the carbon dioxide emitted when the synthetic fuel is burnt will match the CO2 required to be captured in order to make the fuel in the first place.

Early sustainable fuels are made today using the carbon in waste organic matter ('biomass') but the volumes available globally are a tiny fraction of today's needs for energy. The carbon atoms necessary for ultra-low fuels will eventually have to come from CO2 largely captured from the air. The probability is that more than 90% of green oils and gases will be using carbon taken from the atmosphere.

Many aviation and shipping operators are already pursuing synthetic alternatives. Parts of the shipping industry in particular are shifting to building new ships that can use methanol (chemical formula CH3OH) made directly from hydrogen and CO2. These ships are termed 'dual fuel' because they retain the capacity to use conventional fossil fuels alongside methanol.