Jarno Coone, the winner of the international 'world's ugliest lawn' competition, says he doesn't let his garden grow wild to annoy his neighbours in the regional Victorian town of Kyneton. He says he is 'proud to get the message out there for water conservation and living more harmoniously with nature'. 'I really do believe it is better for the environment,' he says

Continue reading...This week's best wildlife photographs from around the world

Continue reading...This is #50 in a series of month-end reflections on the state of the world, and other things that come to mind, as I walk, hike, and explore in my local community.

image by AI based on the 'word portrait' below; my own prompt

Sometimes I try to draw a 'portrait' of my community, just as it is. Not as I judge it to be, with my dubious interpretations of the 'meaning' of people's actions. Just writing what I see, in its entirety, uncensored, un-retouched, un-selective.

Do painters, when they make portraits, toy with the truth the same way writers seemingly can't avoid doing? Is this why we are so fascinated by photographs, which purport to represent exactly what we see, nothing more or less?

I'm sitting in my local café, just trying to notice without attaching meaning to what I see.

Two young Korean women are talking excitedly in the café. Lots of animated, unrestrained body language and facial expressions. They're speaking loudly, in English.

I think the above paragraph is factual. No judgement or interpretation or meaning-making. I could have said they were talking "happily", but then I'm adding my own layer on top of what is just, apparently happening. They are smiling, so it wouldn't be an unreasonable assumption. But still, it's an assumption. A puppy watching them, if puppies could speak with us, would not quibble with the paragraph, but would assuredly not judge the women to be necessarily happy, as human observers would be inclined to do. And the AI image the word prompt produced, above, is eerily close to what I am observing at this moment.

It's quite a performance. I find it hard to resist watching them. It's like watching theatre. Confident, seemingly-almost-rehearsed, exaggerated, demonstrative motions. The words, which I catch only intermittently over the café's music system, don't really matter. (A large proportion of them are the single interjection/filler word like, anyway.) The above paragraph captures, I think, more than a photograph could. More like what a video might capture, perhaps. But their actions seem larger than life, more than mere pixels could ever represent.

How would a painter portray this scene? How could she capture more than a photo could? Could she avoid adding her 'interpretation' of what she was watching? Would that be a good thing or a bad thing? She might use colour and framing to suggest dynamic focus and movement. Her painting might simultaneously capture several actions that actually happened separately — artistic licence. How might she draw their faces to capture something that I, a casual observer, miss? Something no camera could convey.

And of course I can't remove you, the reader, from this 'picture' either. As I write, I'm making assumptions about you, like: When will this guy stop with this boring tangential stuff and provide us with some heartwarming anecdotes showing the humanity of his community, and bring a smile to our face or a tear to our eye? Entertain us, Mr Pollard!

I don't suppose you'll buy my 'no-free-will' argument. Not again.

If I were to draw some more unembellished 'word portraits' about what it's like here, now, on a chilly January west-coast winter day, they might include:

Four grizzled-looking men of mixed ages are sitting together, smoking, and drinking from a shared thermos, in a small clearing at the picturesque intersection of two walking paths by the river. They're wearing threadbare coats, some cloth, some 'puffy', against the 5ºC weather. They smile (a bit inauthentically, or apologetically?) as a woman walking a small dog passes by, and again as I pass by.

Damn it's hard to avoid adding 'interpretation'. Words are so f*&$% lame!

At the edge of the kids' play area in the local park, two parents reach down and zip/velcro up their impatient kids' winter coats. The kids race off toward the swings and, laughing, grab the last two unoccupied ones. The boy has already unzipped and tossed his coat aside. The parents stand nearby, gloved and scarved, rocking back and forth. 'Mom' wears a grim smile and raised eyebrows.

———

In the mall, a teenaged girl takes the hand of the boy walking beside her. He shakes it off. She stops walking. He stops walking. They exchange words. He shrugs. She walks around behind him and puts her arms around him from behind, whispering in his ear. Then she walks around beside him and offers her hand. He takes it, and they continue on their way.

———

Walking back from the mall, I see one of the community's 'regulars', to whom I often give small amounts of money, sitting on the cold cement outside the Walmart with his cardboard sign lamenting his illness and poverty. He is being pressed to 'move on' by the security guard. Two women are shouting at the security guard, insisting the homeless guy's not hassling customers, or trespassing, and hasn't the guard something better to do with his time? The guard responds that after 'three warnings' the Walmart boss told him to call the cops if he shows up again. When the women threaten to complain to management or even organize a boycott of the store, the guard asks them to please not do that (he clearly can't afford to lose this miserable job) and to try to understand his position. The women tell the guard that he should try to understand the homeless guy's position.

———

Later that day, I am taking the pre-sorted garbage down from my apartment to the basement garbage room. A woman gets on at a lower floor, likewise laden with bags full of garbage and recycling. She nods and smiles. I comment "It's like an obstacle course, isn't it, navigating the heavy card-controlled security doors with your arms full? Not fun!" She replies: "I don't know. Anything can be fun. It's all about what you make of it." She laughs as she exits the elevator.

———

And my favourite from the past month:

I'm walking outside the mall in an area set up with ping pong tables (usually in use even in the coldest weather) that, in the summer, features a DJ, foosball, and organized games with prizes. In January, it's empty except for ping pong players and people entering and leaving the mall. There's a woman walking with two little girls, one on either side of her, both of them wearing wireless earbuds. Suddenly, the girls break stride and call for the woman to stop. Then, they do a synchronized clap, eight times, and then break into a line dance! Several people (including me) stop to watch. They continue, completely in step with each other (I later found out you can sync bluetooth signals to be heard by more than one listener at the same time). The dance continues for probably a couple of minutes. Then they stop, and announce to the woman "Canadian Stomp!". Applause from the woman and the small audience. Bows from the girls. The woman replies "Why's it called the Canadian Stomp?" to which one of the girls replies: "Shania Twain, duh!".

———

That's what seems to be happening here, now, anyway.

A very short summary of what has been a long and frustrating process:

I'm on the Board of a small American non-profit charity. It has a single product that it sells at cost, raising enough money (about $3,000/year) to enable us to keep adequate stock.

We sell the product using the Shopify e-commerce platform. Since they offered a slightly higher interest rate on 'balances' left with it than our regular bank, we chose to leave our proceeds there, and only withdraw money when we needed to purchase more stock or to pay postage or other charges.

Huge mistake. We didn't realize:

- Shopify (and its competitors all follow the same practice) outsources its banking to a series of 'virtual' banks to save the cost of FDIC registration themselves.

- The #&%(^ management of Shopify (and again, research suggests all its competitors do the same) signed legal agreements with these 'banking partners' that give these banks unrestricted and unlimited access and rights with respect to our money (Shopify's customers' money).

- Those rights include the right to seize moneys in those accounts without notice, without providing cause, without any time limit, and without even identifying to Shopify's customers which bank has seized their funds. Shopify (and its competitors) have to 'front' and deflect their customers' outrage and ire while the banks have absconded with our money.

If this sounds very much like the actions of Trump's goons seizing the bank accounts of anyone in the world they take a dislike to, that's because basically it is. I am astonished that this is legal, even in a corporatized pseudo-democracy like the US.

In our situation, the unidentified bank stole (seized, froze) our entire bank account 'balance' — the working capital we use to keep our little charity going — equal to several years' revenues, and blocked us from accessing it for five months. I spent over 100 hours of my time trying to get an explanation of the seizure and to get our money back. I was required to provide extensive information about our charity to the anonymous bank, via Shopify, a process that was accusatory and intimidating. When the bank finally completed its supposed 'investigation', about which we were told nothing, they released our funds, with no explanation, no apology, and no assurances they wouldn't do it again.

So the lesson is:

If you are using an e-commerce platform for your business' or charity's sales, never under any circumstances leave even a penny of your sales proceeds in the platform's 'balance' account. Transfer it immediately to your organization's own bank or credit union account. Or be prepared to lose it.

Again, to emphasize, this is not specific to Shopify. All the e-commerce platforms I found have similar arrangements with similar anonymous 'banking partners'. In fact, the woman from Shopify assigned to our account was extremely patient and polite in telling us what little they told her. (I can't say the same for Shopify's management, which has IMO a rather unsavoury relationship with Canada's extremist Conservative party, and which wants a "DOGE for Canada", and which of course blocks aggrieved customers from having any access to management.)

This, it seems, is the world we live in now. Incompetent corporations and megalomanic political leaders harassing innocent people and stealing their money and property with impunity.

There oughta be a law. There used to be, I think.

What is it about human nature that once someone becomes extremely famous or powerful, we become somehow incapable of pointing out when they've become simply bonkers, and need to be quickly put out to pasture before they do things that are illegal and dangerous? Dementia happens, you know? It's tragic. But why are we so desperate to pretend it isn't happening?

We grant this unwarranted and misguided adulation to old people who have lost it in every walk of public life from royalty to rock stars. With Biden, it became ridiculous. The brain-dead geezer had to be told where to walk and exactly what to say, and even when he started reading the parenthesized guides on his cue cards ("pause here for applause") as words to be spoken, everyone from party faithful to the cowed media kept looking the other way with nervous embarrassment, or just outright denied that he was simply non compos mentis.

And then we have RFK Jr with his self-admitted "brain worm" and his collection of dead animals, whose own family has admitted he's lost it, wreaking havoc with the already-collapsing US health system, and aside from gentle satire on late-night talk shows, no one will say the obvious, and get him out of there before he causes millions of deaths.

Of course Exhibit A is the orange-faced one, the guy with the "grab 'em by the pussy" philosophy. His dementia was clear even when he was running against Biden. But here's his latest, and his handlers still aren't making a move to rein him in:

Dear Ambassador:

President Trump has asked that the following message, shared with [Norwegian] Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, be forwarded to your [named head of government/state]

"Dear Jonas: Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace, although it will always be predominant, but can now think about what is good and proper for the United States of America. Denmark cannot protect that land from Russia or China, and why do they have a "right of ownership" anyway? There are no written documents, it's only that a boat landed there hundreds of years ago, but we had boats landing there, also. I have done more for NATO than any other person since its founding, and now, NATO should do something for the United States. The World is not secure unless we have Complete and Total Control of Greenland. Thank you! President DJT"

The first time I saw this, I thought it had to be a joke. Surely this isn't actually being sent, unedited, through official diplomatic channels? But it is.

And the only people upset about it, it seems, are those seeing it as part of a coordinated fascist strategy for global domination. When in fact it's just the ravings of a seriously demented man whose handlers seem completely incapable of recognizing and acting on the man's now-dangerous mental illness.

This man is not a fascist. He has never had the cognitive skills, the knowledge of history, or the attention span to hold any kind of consistent, coherent political strategy or philosophy in his head for more than fifteen minutes. He changes his mind every moment like a two-year-old announcing what he wants for supper. He doesn't have policies, he has temper tantrums. These are signs of senile psychosis, not ideological zeal.

I can understand why Republicans continue to support him and deny he is incapable of doing the job they nominated him for. They don't want to be the next victims of his psychosis, and don't want to admit they are responsible for him.

But I don't understand the cowardice of the Democrats to say what they finally got up the courage to admit of their own nominee. And I don't understand the reticence of the US media to call this what it is, either.

What will it take for them to say the obvious — their president is a seriously demented man who quickly needs to be removed from power? The only difference between him and Biden is that Biden was a placid psychotic when he lost it, while Trump is a violent one.

image by AI; my own prompt

This is the second of a series of articles — opinionated, fanciful writings, speculations — about The World After Collapse. It draws on what I've learned about pre-civilization humans and other large-brained creatures, and speculates on how, after civilization's fall is complete — probably centuries from now — the remnants of the human species might be unrecognizably different from how we behave and think now. But they may be also 'recognizably' similar to how we know, deep down inside, we really are, and always have been. The series is not intended to provide hope, or solace, or a prediction, or least of all a pathway to change. Just a speculation about how the world, with a smaller number of us, or without us, might look long after those of us living through the fall have gone.

What's the point, I have been asked, of writing speculations about the world after civilization's collapse, especially when it appears likely that the current collapse is likely to continue for centuries?

I think the 'point' might be as an act of forgiveness. And we all need a little forgiveness.

For 20+ years I've been trying to explain why the accelerating collapse of our civilization was/is inevitable (that's just how complex systems work) and that it's not our 'fault' (we have no free will and our behaviour is entirely conditioned).

Unlike those who approach this realization with a sense of immense grief (with commensurate processes and rituals for dealing with it), I've always tried (and been conditioned) to approach it with a sense of equanimity, the way I think wild animals do. I'm more drawn to the social forgetting process than the truth and reconciliation process. I see dragging up past trauma, assigning blame, and insisting on confession and apology, as an inherently western religion-based pathology, one dependent on belief in intrinsic sinfulness and free will. It is easier to forgive, and to forget, when one accepts that everything that has happened could not have been otherwise.

from the membrary

Assuming it will take centuries, perhaps even millennia, for the current collapse to play out (given the unprecedented size and complexity of our current civilization), what might our post-civ human societies look like?

I think, based on the preponderance of evidence I have read, that there's an uncomfortably high likelihood that the post-civ world will not have any humans in it. We are, after all, a fragile species, naturally suited only to the relatively scarce environments of tropical rainforests and hence utterly dependent, since we left them, on a completely synthetic, prosthetic 'human environment' for our survival. There will not be the resources left to construct such synthetic environments after collapse, and in any case post-civ natural environments are likely to be much less stable and more hostile and volatile than they have been for the past few millennia.

So my sense is that, if there are any human societies left, it will be because they have avoided the tendencies that have doomed our current civilization. One of those tendencies is a proclivity for the kind of specialization that enables the growth of larger and more complex societies at the cost of individual competence, independence and resilience.

The collective recognition and selection of certain of us as being 'better at' doing some things is understandable, and has likely been part of the reason we survived as a species once we had been forced to leave our ancestral forest home. But the purpose of that recognition is to enable the rest to learn from watching and emulating that person.

That specialization however is fetishized in modern society, to the point most of us have become completely incompetent at doing most of the things that are absolutely essential to our survival and health, and hence utterly dependent on those who are competent (if you can still find them), and on the massively complex systems that enable (increasingly feebly) the competent to do things for us that we need done. This dependence is abnormal and completely unsustainable. And those with wealth and power relish and exploit our complete dependence on these massive systems that they control and draw 'rents' from.

If, as I suspect, any post-civ human societies will necessarily be much smaller than today's, they will of necessity also become more egalitarian, and they will not be able to afford dependency. If person X is the only one who knows how to do essential function Y well, then X had better teach the rest of the tribe all about Y before he gets eaten by a creature higher up in the food chain. The upshot is that post-civ humans will, I think, inevitably be competent in everything they need to know to do to survive and thrive, not to be independent, but to be interdependent with their tribe-mates, ensuring maximal capacity and competence for the entire tribe. If they aren't, then our species will quickly go extinct.

A second human tendency that I think has led to our current civilization's demise is a strange and seemingly uniquely belief that life is more important than health, pleasure and happiness. This is, again, an entrained human belief inculcated by most human religions, as well as by loony spiritual cults like Musk's Longtermism.

Most wild creatures, when they lose their health, opt to go off by themselves to die, rather than burden their tribe with support needs that endanger the safety and viability of the whole. And wild creatures (contrary to prevailing and IMO adversarial and wrong-headed 'selfish gene' memes) naturally balance their numbers and the extents of their habitats for the benefit of all life in their environments. That's because they do not conceive of themselves as separate from, or inherently threatened by, the rest of life in their environments. The goal, built into millions of years of evolution, is the survival and thriving of the whole.

Could our species somehow evolve, after collapse, without this traumatizing, horrifically destructive sense of separation and superiority to the rest of the planet's life? That's probably the question that fascinates me the most these days. I've argued that this sense evolved as an accidental spandrel of our species' evolving large brain and specifically the entanglement of parts of our brain that are entirely separate in other species' brains. It would also seem that this entanglement and its traumatizing consequences (including what we call 'consciousness') are recent developments in our species, and co-evolved with language and settlement in large numbers (greater than Dunbar's number).

The development and use of language is a huge, high-maintenance and energy-consuming component of our human metabolism. That language use occupies (and re-wires) a large proportion of our brains' circuitry, and hence 'crowds out' a lot of other brain functions that we have lost in our recent evolution. Recent research suggests we evolved language to strengthen social connections as groups got larger, and not because we 'needed' it for our survival. In fact, there is considerable evidence (see Ludovic Slimak's book) that H. Neanderthalensis didn't need it or develop it, and that we exterminated them because their 'difference' terrified us, while our difference from them didn't faze them at all (all just part of the whole).

I think it is conceivable that, if and when we cease needing abstract language, and our brains once again begin developing from infancy for their primal purposes (maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain, to oversimplify), that we will once again become, like all other life on Earth, creatures that communicate via obvious instinctive gestures and not by complex hard-to-learn abstract language. And maybe, just maybe, our future descendants' brains will then again become incapable of learning abstract languages (see Noam Chomsky et al's work on how children not taught such languages by adolescence become incapable of learning them afterwards — their brain structures have evolved in incompatible ways).

And without language, I think, all of the conceptual baggage that sits on language's scaffolding — including the very ideas of 'self' and 'separation' and the terror and trauma that those concepts inevitably sparked in us — will likewise cease to arise. We will, at last, be as emotionally healthy as the rest of life on Earth. And, with that superior emotional health, we will cease obsessing about sustaining our (conceived, imagined, separate, desperate) lives regardless of our physical health. We (or at least our bodies) will become (like some indigenous peoples still are) far more careful not to endanger our physical health than we are now. A healthy life will become more important than a long one.

So, I think it's possible, or perhaps it's just wishful thinking, that any post-civ societies, as necessarily smaller and simpler than ours as they will be, will be far more competent and far more healthy than our horrifically dependent, narrowly (if at all) competent, sickly species. And they will just be part of the larger organism of all-life-on-Earth.

That hope, that tentative belief, allows me to forgive myself and others for this civilization's collapse and all the damage it has produced and will continue to produce.

After us, the dragons. And if there are some of our species left, we will in any case not be dragon-slayers. After all, there is no separation between us and the dragons. And in any case there is no such thing as a dragon.

In January 1933, Hitler is appointed Chancellor despite only minority support in the election. A few months later, he becomes dictator and all opposition parties are banned. Image via Anne Frank House from Bundesarchiv, 146-1972-026-11/ photograph: R. Sennecke. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Rights: CC-BY-SA 3.0 DE

Word of the day is 'latibulate' (17th century): to hide in a corner in an attempt to escape reality.

— Susie Dent, from the memebrary

It really does seem as if the American Empire, with the complicity of both US parties, most major corporations, the corporate-owned media, and the cowardly, appeasing leaders of the other countries in the larger White Empire, is hell-bent on emulating the 'rise' and world domination aspirations of Germany in the 1930s. The parallels are now too overwhelming to ignore.

Independent Canadian journalist Tod Maffin likens the behaviour of the US Administration to that of a school bully. The analogy is perfectly apt. The UN and the courts are the hapless school authorities. The Canadian/European/Australian 'leaders' are the bully's terrified 'allies' and apologists for the bully's behaviour, out of fear and incomprehension they will be next. They're fine with the brutality and theft as long as it's the poor, weak kids getting beaten up and robbed, not them. I suppose we hope that the bully will 'graduate out' of the school in the next US election, and the problem will magically disappear. That's what the world figured in the early 1930s about Germany.

In the meantime, Canadians are now at least talking about the probability of annexation, military intervention, economic sanctions (sieges) and other hostile actions threatening our sovereignty.

It is absolutely conceivable that the carnage will continue until all of the Americas, and the entire Middle East, has been declared the bully's territory. The bully will continue his behaviour until he stops getting exactly what he wants and demands. Just like in the 1930s. ICE killed 32 people last year, and has over 68,000 locked up, mostly without charges. Just like in the 1930s. Their target is "100 million", to enable an Aryan US Empire "no longer besieged by the third world". Just like in the 1930s.

First they came for the Communists…

COLLAPSE WATCH

photo via Bill Rees' blog, by Emre Ezer on Pexels, free to use

Is the looming financial collapse behind Trump's war-mongering?: Tim Morgan poses an interesting thesis: If as most believe financial 'assets' are ludicrous overvalued (especially AI 'assets'), and if (see Lawrence Wilkerson's article linked below) the massive government and private debt that has been created to try to keep the economy pumping is basically un-repayable when it comes due, then this suggests that countries dependent on financial 'wealth' (the US, and Europe to a lesser extent) are facing catastrophic economic collapse and contraction, while countries that rely on their material resources (China, Russia, Canada, Venezuela, Iran) should be able to weather the storm relatively well. What's a resource-poor, finance-dependent country to do? Well, obviously, steal the resource-rich countries' resources (oil, land, water, minerals) to lessen the blow.

Why collapse is inevitable: A 3-part essay from ecological economist Bill Rees. Bill's summary:

- Part 1 argues that modern humans are maladapted by nature and nurture to the world they themselves have created. Our paleolithic brains are befuddled by the sheer scale, complexity and pace of change of both our socio-cultural and biophysical environments.

- Part 2 suggests that much of our befuddlement is due to unfamiliar behaviours and circumstances that emerge from the internal machinations of large-scale societal organizations and their interactions with the biophysical systems that contain them. Our Paleolithic brains are not up to the challenge. Socially stable, eco-compatible large-scale societies cannot emerge from these turbulent confrontations.

- Part 3 makes the case that what does emerge is something else altogether—gross societal malfunction-to-collapse—which may be at least partially explained by pan-cultural 'psychopathy'.

This month in collapse: Erik Michaels provides a comprehensive and compelling summary of the best new writing on collapse, every week. Definitely worth subscribing or putting in your RSS feed. His latest includes this remarkable paragraph from ecologist Lyle Lewis:

We often end [discussions about extinction] with reassurance; with the idea that we can still choose how deep the crater goes. But history offers little evidence that we can. Knowledge without the capacity to act is irrelevant, and our species has always followed the same imperative: to consume what sustains us until it's gone. The truth is that this extinction isn't a problem we can solve; it's a process we set in motion simply by being what we are. All that remains is to bear witness; to understand what it means to live in the final stages of the unmaking of the world. In truth, every hominin of the last 2.5 million years has lived somewhere along this descent; life will go on, but not the life we've known. We're simply witnesses to its undoing.

Orange rivers as the permafrost melts: A new NOAA study reveals how quickly the Arctic environment is changing as polar temperatures rise 3-5x faster than they are on the rest of the planet. And in the process Canada is quickly and irreplaceably losing its glaciers.

LIVING BETTER

via Stephen Abram, originally from a pro-vaccine site

It starts with humility: Those of us privileged to have obtained advanced degrees and high salaries and powerful-sounding titles can easily begin to believe our own press — that what we have to say is important and invariably right. It came as a shock to me when I retired to discover most of the stuff in my professional bio was just self-serving crap, and that I really had not accomplished anything of enduring value. And that all the people I worked for and with likewise had not accomplished anything of enduring value — and the more they had been paid and the 'higher up' they went, the more that was true. Not because any of us were/are dumb or incompetent (though some were), but because that's not how sustained, lasting change happens in complex systems. It sounds like Mark Eddleston has had a similar epiphany, and he's written an articulate and achingly humble book about it. First chapter is here.

Seven ways to make housing affordable: Now that Vancouver housing prices have stabilized, there's a new opportunity for governments to help residents cut the absurd cost of housing, that apply just about everywhere. "Letting the market" solve the problems has never worked.

Getting religion out of the health care system: Finally, BC's courts have been forced to confront the absurdity of publicly-funded hospitals dictating health care policy based on religious orthodoxy.

POLITICS AND ECONOMICS AS USUAL

produced, apparently by accident, by AI (not my prompt); out of the mouth of bots

Patrick Lawrence's eulogy for the rule of law as the world descends into chaos: Patrick's a wonderful writer, and his three latest essays should be required reading for anyone who wants to understand what's happening in the world. I'm providing multiple links to try to skirt the paywall (let me know if you can't access any of them), and have asked him to 'package' and release them for wider distribution:

- 1. Free Speech and It's Enemies: What we're able and competent to say and write has a powerful impact on what we're able to conceive and think. (CN copy.)

- 2. The Coup: The American Empire baldly announces what has been its covert modus operandi for decades: It claims the entire Western Hemisphere (and the Middle East) as its territory to deal with as it chooses, and recognizes none of these nations' sovereignty. (Alt Substack copy.)

- 3. An Abyss of Lawlessness: In the words of Trump cabinet minister Stephen Miller: "We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time. The "rule of law" is one of those "international niceties" that has been completely discarded. (CN copy)

Imperialism, Militarism & Fascism: Short takes:

- Lawrence Wilkerson predicts that $3T in US government debt imminently coming due will bring down the US economy, and Trump's military adventures and thefts are all desperate smokescreens to try to cushion the collapse. Quiet backroom deals with China and Russia will be needed to prevent it turning into a global economic collapse.

- And in a related vein, the inevitable shift to a multipolar world is explained by Arnaud Bertrand.

- Indrajit explains why the likely reason China and Russia aren't doing more than condemning the most recent US atrocities is because they're smart enough to realize that those atrocities are backfiring (citing Napoleon: "Never interfere with your enemy when he is making a mistake.").

- Israel bans Doctors Without Borders and dozens of other humanitarian organizations from Palestine.

- The brutal War in Sudan is a civil war between two greedy militias; just follow the money.

- Indrajit Samarajiva's clever analogy to the US/White Empire going "white dwarf" as it explodes and then collapses.

- The son of a Chilean Nazi, who's also an overt supporter of the brutal Pinochet dictatorship, has won the presidency of Chile.

Propaganda, Censorship, Misinformation and Disinformation: Short takes:

- Mossad, whose agents are deployed in large numbers in Iran, and whose infiltration inside Iran crippled the country's response to last summer's US/Israeli bombings, is actively involved in fomenting violence among the protestors demonstrating against shortages in that country, with the goal of turning the protests into anti-regime demonstrations, trying to trigger a violent response from the Iranian government to enable new planned US/Israeli bombings and regime change operations. The western press continues to ignore and censor reports of Mossad's active involvement in creating a smokescreen for another war against Iran. But some "third world" countries are reporting on it. Here's a report from India on Mossad's activities. And of course Caitlin is also all over it. And Larry Johnson has an update. And Moon of Alabama says the pro-government protests now dramatically outnumber the anti-government protests.

- How the US/Israeli propaganda campaign deliberately exploits public confusion, exhaustion, and disbelief, while sowing fear of daring to protest throughout the west.

- Jeremy Corbyn laments Starmer's continued abject submission to the US on its recent war crimes.

- The US/western media refuse to call Trump's attack and war crimes in Venezuela "acts of war".

- Dozens of western media used the identical headline terms in response to the Bondi shooting: "The globalized Intifada comes to Boston". Coincidence?

- The NYT continues to report on the US/Israeli genocide in Palestine as acts of "law enforcement".

Corpocracy & Unregulated Capitalism: Short takes:

- A Goldman exec explains how they encourage the 'pump and dump' scam to exploit uncertainty over the economic situation, and to make a quick buck on AI.

- How to deal with corrupt corporations, and how to fix unions that discriminate against new members (very different problems).

- How the 'financial industry' is just a casino: "In our society the classic three ways of making a fortune still apply: inherit it, marry it, or steal it. But for an ordinary citizen who wants to become rich through working at a salaried job, finance is by an enormous margin the most likely path. And yet, the thing they're doing in finance is useless. I mean that in a strong sense: this activity produces nothing and creates no benefit for society in aggregate, because every gain is matched by an identical loss. It all sums to zero."

- The Skeena Resources mining company offered $10,000 bribes to First Nations members to approve the mine's reopening.

- Cory Doctorow explains in detail why he thinks it's so important for our economy and for tacking inequality to repeal the "anti-circumvention laws" most countries have agreed to sign as part of trade agreements, which funnel staggering amounts of money to giant US corporations for doing essentially nothing, and hamper national innovation in the process. Not an easy read, but this is important to understand.

Administrative Mismanagement & Incompetence: Short takes:

- The US CDC has slashed most of its recommendations for childhood vaccinations, based entirely on RFK Jr's ideology, and contrary to all established science on the benefits and risks of these vaccines, putting millions of children at risk.

Department of Health Prevention: Short takes:

- As a result of the aforementioned RFK Jr incompetence, the public health community has rallied in support of the American Academy of Pediatrics, which continues to advocate for a full slate of safety-proven vaccinations. Many US state health organizations are also supporting them.

- The brain-wormed Health Secretary has also turned the 'food pyramid' of foods recommended for a healthy diet upside down. Red meat and dairy (the country's largest Big Ag lobbies and biggest sources of saturated fats) have been elevated to the wide top of the pyramid, and whole grains and nuts apparently demoted to the very bottom. In delivering its confusing, anti-science, ideological message, the deranged Kennedy said that the stuff at the bottom is also important, but that's not how the bizarre diagram reads. Absolutely appalling, but fortunately most Americans ignore 'food pyramids' anyway; we can only hope they will continue to do so.

- Influenza cases and deaths in the US (and likely Canada) have reached the highest levels since CoVid-19 years.

- Soaring health care insurance costs in the US are forcing some Americans to marry their housemates.

FUN AND INSPIRATION

from the memebrary

Does a mirror reflect a past version of yourself?: Yes, says Hank Green, scientifically that's true. But actually "your self is an illusion, a fake idea created through a process of natural selection to successfully pass on its genes to the next generation… Your body is a prison".

The curious case of Earl Mardle's cow: The cow's behaviour suggests an odd mix of instinctive and 'judgemental' reactions to a challenging situation. The long and complex story is worth a read. It just might contain clues to whether cows do or don't have "selves".

Vancouver's soaring vacancy rates: It's perplexing — the city is one of the world's most popular places to live and retire, and among the world's most expensive, but its rental vacancy rates have jumped from near-zero to 40-year record highs. Why? Not government policy or increased supply, say the experts. The Tyee reports the real reasons: Reduced demand as rental prices stayed high and renters' disposable income dropped (so renters doubled up or moved away). A sharp drop in non-permanent residents, as Canada fell in line with Trump's anti-immigration rhetoric and cut quotas. And "a sluggish retail market" as owners who'd bought properties to speculate on continuing price rises gave up trying to resell them and put them on the rental market. That's not just true in Vancouver, I'd venture to say.

Rick Beato's personal favourite songs of 2025: Taste is so tricky to understand. Rick is an expert, and I do like his choices better than the actual top sellers per Spotify (except for Die With a Smile, which IMO is already a classic). But otherwise, my favourites didn't overlap at all with either list.

What do you mean by 'India'?: Indrajit Samarajiva provides a fascinating explanation of how most people's sense of 'where they live' has nothing to do with what politicians talk about or where mapmakers draw the lines.

What reading does to your brain: OK, so there's the orthodox view on this, how reading makes you think better and improves "attention, memory and empathy", which this video covers. (Thanks to Liz 'Oofdah' for the link.) But I don't think the author realizes that reading crowds out a lot of other potential uses of your brain's capacity (and no, it's a myth that we only use 20% of our brains). And reading can also lead to groupthink, acceptance of propaganda, and entrenchment of beliefs that are simply not true. So much depends on what and how you read.

The "impossible" machines that manufacture the world's most advanced computer chips: Were it not for these machines, decades in the making against high odds and doubts, Moore's Law would have broken by now, and our computers would be much slower and bulkier.

The arrest of Mark Carney will bring peace and prosperity: A clever satirical 'editorial' that draws whole sentences from the official text of Trump's kidnapping of Maduro, to propose that the Canadian PM likewise be 'arrested'.

THOUGHTS OF THE MONTH

from the memebrary — apparently a collaboration between those cited at bottom

From a transcription of Trump's press conference after kidnapping Maduro and bombing Caracas and its port city (thanks to Caitlin Johnstone for telling us what he actually said, rather than what they think he might have meant):

We're gonna take back the oil that frankly we should have taken back a long time ago… We're going to be taking out a tremendous amount of wealth out of the ground, and that wealth is going to the people of Venezuela, and people from outside of Venezuela that used to be in Venezuela, and it goes also to the United States of America in the form of reimbursement for the damages caused us by that country.

We're going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country, and we are ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to do so… We have tremendous energy in that country. It's very important that we protect it. We need that for ourselves, we need that for the world…

We're going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition. So we don't want to be involved with having somebody else get in… We're not afraid of boots on the ground. And we have to have, we had boots on the ground last night at a very high level.

[to Fox News] This incredible thing last night… We have to do it again [in other countries]. We can do it again, too. Nobody can stop us.

From the speech by Venezuela's VP and now de facto President Delcy Rodríguez, immediately after Trump's kidnapping of Maduro and the bombing of Caracas and attempted theft of its oil (via Moon of Alabama; once again, you won't find much mention of this in western media):

The objective of this attack is none other than to seize Venezuela's strategic resources, particularly its oil and minerals, in an attempt to forcibly break the nation's political independence. They will not succeed. After more than 200 years of independence, the people and their legitimate government remain steadfast in defending their sovereignty and their inalienable right to decide their own destiny. The attempt to impose a colonial war to destroy the republican form of government and force a "regime change," in alliance with the fascist oligarchy, will fail like all previous attempts.

From Hank Green: A couple of clever remarks from recent Vlogbrothers videos:

AI is Wealth's attempt to gain access to Skill while preventing Skill from having access to Wealth.

[Too much of social media is] grievance-based-attention farming.

From Dorianne Laux's The Book of Men:

DARK CHARMS

Eventually the future shows up everywhere:

those burly summers and unslept nights in deep

lines and dark splotches, thinning skin.

Here's the corner store grown to a condo,

the bike reduced to one spinning wheel,

the ghost of a dog that used to be, her trail

no longer trodden, just a dip in the weeds.

The clear water we drank as thirsty children

still runs through our veins. Stars we saw then

we still see now, only fewer, dimmer, less often.

The old tunes play and continue to move us

in spite of our learning, the wraith of romance,

lost innocence, literature, the death of the poets.

We continue to speak, if only in whispers,

to something inside us that longs to be named.

We name it the past and drag it behind us,

bag like a lung filled with shadow and song,

dreams of running, the keys to lost names.

This is a work of fiction. Note that if you're reading this in an e-newsletter, the table in this story might be hard to read. You can always read the copy on the blog.

"Uh oh. Cat's up to something crazy again. OK, so what's this — a map for solving all the world's problems?

"It's a game board, Dev. I've invented a new game based on ikigai. It can be used as an ice-breaker, to help people who don't know each other discover things they enjoy in common. Or it can be used by people who do know each other to learn more about each other, and see how well they know each other."

"So… an ice-breaker or a relationship-breaker. Sounds very dangerous."

"Maybe if there's things that are important to someone you love, that you're completely unaware of, it might be better to know about them than remain not-so-blissfully ignorant? But the main purpose of the game is to have fun. It's based a little on the old party game "Would You Rather?", and the more recent "Personal Preference" game but this has important differences. Want to know how it works?"

"Sure. One of the things on my ikigai list is making the women I care about in my life happy. Go for it."

"OK, so, this game can be played by any number of players, but this layout you see represents four players. Let's assume they're people who don't know each other that well, like the people at our monthly Vegan Potluck coming up this weekend, since that's when I thought about introducing this game."

"With you so far."

"The game consists of a fixed number of rounds, let's say 24 'cause it divides evenly into lots of different group sizes. Each round consists of one player reading out a sentence that starts with 'Would it bring you joy to: [A]___ [B]___ [C]___?", where A, B and C are three roughly similar activities, at least one of which the questioner really likes — maybe something from their ikigai list. So for example: [A] have a bubble bath by candlelight with someone you love; [B] spend time in a hot tub with a group of friends and a bottle of wine; [C] spend time in a sauna with three friends giving each other massages. And then using tiles with zero, one, or two stars printed on them, each player puts a green tile with the appropriate number of stars on the card in front of them, face down, under each of the three letters, to indicate whether they wouldn't get joy from that (0 stars), would get a little joy from it (1 star), or would get enormous joy from doing it (2 stars)."

"Ooh. Some of those things would merit five stars from me."

"And then, each player (other than the questioner), uses the same scoring system and the blue tiles to guess what the questioner's own preferences for those three things would be (also face down). Your answers can all be two stars, or all zero stars, or any combination of stars. (Except that, if this is the questioner's own question, rather than one from the 'starter' deck, then at least one of the questioner's own preferences has to be two-stars, something on their ikigai list.)"

"What if options [A], [B] and [C} are so different that they're not comparable, like if in your example [B] was eating raspberries and [C] was skydiving?"

"That's why this game is better than the binary-choice 'Would You Rather?' games. They don't have to be comparable, though I think it makes it more interesting if they are. What's important is that the choices have to be concrete and realistic, not theoretical, impossible or silly. So no "Walk on the moon" options or "Find a million dollars on the sidewalk" options. These are about real things that you could quite conceivably do.

"So now, the questioner turns over their green tiles, and then each person in order, around the circle, turns over their green and blue tiles. The key part of the game is now the conversation that ensues about why people answered as they did. And perhaps some expressions of astonishment about what some of us would realistically love the chance to do."

"I can see this working for people who have explored the ikigai idea and put together a list of the things that bring them joy. But what about for people who've never thought about it?"

"Two options: Either have a 'starter' deck of options for the questioner to ask about, at least until players learn to come up with their own, or alternatively have a 'learn about your ikigai' session before you play, to allow players to come up with some real ikigai options of their own that they can then use in the game."

"I love it, though it's going to raise eyebrows among those who don't know about ikigai, and who maybe even don't know what really gives them joy. They might think this is too much brain challenging work and not enough fun. Same for people who don't have very good imaginations."

"Absolutely true. That might make this whole idea a failure. But I think the 'starter deck' of questions, if it's well-done, might get them over the learning hump. Here's my first cut at some questions for the starter deck:

A B C

Lie on the beach in the sun all day Play in a volleyball tournament on a tropical beach Beachcomb for shells, fossils and driftwood

Learn to pole dance Dance naked in the pouring rain Take Latin dance lessons

Talk with friends about politics Talk with friends about favourite characters from novels Talk with friends about philosophy and science

Tell ghost stories by a campfire Roast chestnuts on a hearth fireplace Attend a bonfire party

Drink matcha lattes Drink egg nogs Drink hibiscus tea

Use a weighted blanket for comfort on a cold night Snuggle with a platonic friend on a cold night Snuggle with a cat on a cold night

Walk on a swinging (suspension) bridge Participate in a 'Deep Time' walk Walk alone in a tropical rainforest

Get a deep tissue massage Spend time in a sensory deprivation tank Get an Ayurvedic oil massage

Flirt with someone from a very different culture Engage in a 'speed dating' activity just for fun Spend an entire day with someone without using any form of language

Play a collaborative board game — one with no winner Dress up and engage in 'furry' play with friends

Play a GPS scavenger hunt game

Listen and dance to EDM music Attend a choral concert Listen to K-Pop music

Engage in clever banter at a party with a group Find one interesting new person at a party and spend time with them Ditch the main party activities and play with the host's cat instead

Play laser tag Play Escape Room Play Fortnite

Write short stories Write essays Write poems

Compose music Sing in a choir Play in a band

Watch murder mystery TV shows Do Sudoku puzzles Do crossword puzzles

Fish Stargaze Birdwatch

Learn to make your own clothes Learn to mend your own clothes Learn to fix your own bicycle

Make pottery on a wheel Paint with acrylics Weave on a loom

Go canoeing Go spelunking Go parasailing

Eat a fudge sundae Eat vegan ice cream with raspberries Eat a S'mores crepe

Participate in a yacht race Participate in a polar bear swim Go up in a hot air balloon

Visit Paris Visit New Zealand Visit China

"And I also hope that the learning and discovery about one's own joys, and others', will more than compensate for the mental energy the game demands."

"Yeah, because we have such 'thoughtful' friends, I think it might work well for them. So… scoring?"

"That's the coolest part. I have a blank laptop spreadsheet that handles it all. Key in the questions in the first column, and everybody's 'green tile' and 'blue tile' answers in the other columns, and the spreadsheet automatically computes two things: (1) How well each player did at correctly guessing the questioners' own answers, and (2) How well each player's own answers correlate with every other player's answers. And displays that information as running totals as the game progresses."

"Uh, oh. So what if Lissa's answers and mine correlate 96%, and yours and mine only correlate 75%. Does that mean I'm hanging around with the wrong smart, beautiful woman?"

"Maybe. Wouldn't it be interesting to know? Maybe if hers and mine also correlate very highly, we should just consider including her in some of the things we do, for everyone's happiness. And maybe it means that Lissa and I should organize some canoeing trips together and leave you on shore to make our favourite dinner and have it ready when we finish our trip."

"That sounds good. But the candle-lit bubble bath afterwards might be a bit of a squeeze for three."

"That's OK. I happen to know Xan loves bubble baths, and he's vegan like you. So you can bathe with Lissa and I can bathe with Xan. Come to think of it, I think he has a hot tub too!"

"GOT MINE!" — An AI depiction of corporatism and 'private equity' as vultures; my own prompt

Politicians' current blathering about the "affordability crisis" is basically an attempt to re-characterize the accelerating global political and economic collapse as a 'hiccup' in the current system that merely requires some expert managerial and financial tweaking.

It's a deception in two senses:

- It attempts to divert attention from the understandable outrage of citizens at the current chaos, massive and soaring inequality, overt corruption, and staggering incompetence of our 'leaders', by reframing citizens as mere 'consumers', who should not worry their pretty little heads about matters of state, but instead focus on how they can buy and spend more.

- It conceals the large-scale theft of money and public resources by a small group of rich, powerful, insatiably rapacious, egomaniacal, terrified billionaires, from the rest of the world's struggling citizens. Without this monstrous diversion of wealth from the poor (and the public purse) to the private pockets of the ultra-rich, there would be no (immediate) "affordability" crisis for the billions of victims of this larceny.

A recent article by Evelyn Quartz explains that this deception (and note that the perpetrators of it are often themselves victims of it) stems in part from "a political class that treats politics as a financing and management problem rather than a question of democratic control". By this thinking, government (ie taxpayers') money should be used primarily to "incentivize" the private sector to do things (by giving them tax breaks, loans, outright gifts, subsidies etc), rather than to actually provide goods and services directly to the citizens footing the bill.

This is not just an abrogation of responsibility (and arguably a fraudulent one), it is an acknowledgement that politicians have given up on the idea of government doing anything competently, so instead of administering a huge public service providing absolute essentials cost-effectively to citizens, they're shrugging their shoulders, giving all the money to private interests, and hoping those private interests don't just take the money and run. Which is, for the most part, exactly what those private interests have done — just look at "private" colleges, "private" 'health care', and "private" equity.

This private sector avarice and incompetence then requires the political class to engage in a relentless program of "perception management": Government and the entire public sector needs to be portrayed as inherently and necessarily inefficient and incompetent, so that giving public funds and wealth to private interests can somehow be seen as wise. And the private sector, of course, then kicks back money to the politicians in the form of campaign donations, writes flattering stories about them in the corporate-owned media, and ghost writes the laws in their favour for the politicians to present as theirs, so that the corruption is guaranteed to continue and worsen.

The struggle of most people to put food on the table, pay the rent or mortgage, and deal with falling wages and lost benefits as the prices of essentials soar, is not an "affordability" problem. The problem is that far too much of the wealth being produced by the rest of us is being siphoned off by a tiny ultra-rich minority, and that our utterly oil-dependent economy is now in permanent decline even as the human population and its demands on the economy continue to soar.

The simple truth of increasing numbers and increasing demands in the face of declining capacity to provide even as much each year as in the previous year, means that there is no longer nearly enough to go around, and the situation is rapidly and inexorably worsening.

This tiny minority siphoning off everything they can get their hands on is completely aware of the accelerating collapse of our economy and what it bodes for the world in the coming decades. They're hoarding for the collapse, exactly as the alpha rats in lab experiments do when food supply is increasingly constrained.

If there is an "affordability" problem, it is that the cost of extracting the increasingly-expensive and heavily-depleted hydrocarbon resources that have provided 100% of global economic growth for the last two centuries is now beyond what the users of those resources can afford to pay. In economic terms, the supply and demand curves no longer intersect, and the inevitable consequence is collapse. This is not an affordability problem, it is an affordability predicament. It has no solution. Collapse cannot be avoided.

But of course the citizens don't want to hear this, so the political class won't tell them. It would reflect badly on the political class' 'management'. Instead, the political class will play the blame game. They will invade oil-rich countries and steal their wealth. Or they will stall off the outrage of citizens by saying it's just an "affordability" problem, and, with citizens' continued, patient support, some technical solutions will soon "fix" it.

Eventually, as the precarity and scarcities get worse and worse, even our dumbed-down, lied-to, propagandized, deceived citizens will wise up to the con.

And then, watch out.

Now that the collapse of our political, economic, social and ecological systems is accelerating, the signs of this collapse, including scapegoating, corruption, and social disorder are becoming more obvious. This is the fourteenth of a series of articles on some of these signposts.

For over 20 years, a British filmmaker named Adam Curtis has been producing an odd series of breathless films, mostly under contract to the BBC, consisting of a blizzard of collages of news headlines, speeches, stills and short video clips, with Adam's background narration of 'what it all means'.

And what it all means, he claims, is:

- For decades, western leaders, unable to present a coherent explanation of the state of the world (both because they don't understand it, and because they lack the language and other competencies needed to articulate it), have been managing their societies by describing a "fake", hyper-simplified world.

- These leaders, the administrations they front, and the compliant media their corporate sponsors have bought, now issue an endless barrage of conflicting statements, contradictory policies, and incoherent rhetorical claims, that are designed to confound any understanding and hence any rational response to what these administrations are doing.

- The citizenry is hence controlled by the paralysis this confusion produces, by fear of what 'really' might be going on beneath all the confusion, and by the manufacture of deliberately overstated, ambiguous and oversimplified threats they feel compelled to try, hopelessly, to counter.

- So the utter incoherence of what is coming from our leaders is not 'just' incompetence and inarticulateness, but rather a deliberate strategy of obfuscation and disorientation to maintain a dysfunctional, desperate and corrupt status quo; it is a 'feature' and not a 'bug' of our current political system.

Hanlon's Razor tells us that we should never attribute to malice what is adequately explained by stupidity.

So what are we to make of this? The staggering level of incompetence evinced by our current crop of 'leaders' is pretty hard to deny. Is Adam seeing an (admittedly uncoordinated) conspiracy where there isn't one?

Looking at the complete state of disarray of citizen opposition to the growing political chaos and irrationality of those with the wealth and power to drastically affect our lives (invariably for the worse), this 'strategy' of incoherence, if there is one, would seem to be working remarkably well.

After all, suppose you're the elected 'leader' of a western government as the world accelerates into an increasing state of anxiety, instability, and 'permanent' economic and ecological decline into collapse. You want to stay in power, because you quite fervently believe that the opposition parties, with platforms driven by stirring up anger, hate and fear at seeing everything falling apart, will 'manage' your country even more incompetently than you, the incumbent, has.

But how do you stay in power when all you have to tell the dumbed-down, scared electorate is bad news they don't want to hear, and when your opposition is stirring up that fear, angrily promising simplistic, impossible, 'if you can't fix it smash it' (or privatize it) solutions to Make Your Country Great Again?

If you pull a Biden-Harris and claim things are actually going well when any fool can see that for most citizens they aren't, you'll get what you deserve. But what's the alternative?

Most people, brainwashed with the myths of exceptionalism, progress. and endless unlimited opportunity for the hard-working, are simply not ready to hear the truth of the inevitability of accelerating chaos and inevitable collapse, and the misery that will accompany it.

So instead we get lies, meaningless promises, 'performative' politics and elections that mostly resemble beauty pageants, and fear-mongering of the opposition parties, regardless of who is in power and what the equally bewildered opposition is. Because there is no platform to address collapse. All we can do is wait and see how it unfolds, and deal with it as best we can. There's no planning for it. Nothing any 'central' authority can prepare for (especially since these 'central' authorities will be the first to fall).

This is what chaos looks like, the last, astonishing, awful chapter of human 'civilization' before its final and total collapse. And how could our response to chaos be anything other than incoherent?

Thanks to Graham Stewart for provoking this post.

image by AI; my own prompt

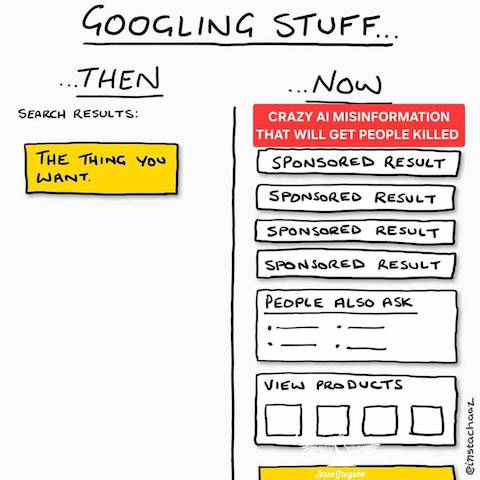

drawing by Chaz Hutton

Now that the internet has degenerated to a sad mishmash of spam, scam, propaganda, disinformation, useless 'apps', and commercial fraud, with a new overlay of AI slop, the question becomes how to best get what we used to get from the internet, through workarounds. Preferably before the stench of the internet's rotting corpse gets too much worse.

Of course the tech bros and their billionaire buddies and corporate oligopolies have thrown everything they can in our paths to prevent this. Through the now thoroughly-documented process of enshittification, they suck us in and lock us down, making it almost impossible to escape their expensive rent-seeking flea market without also losing our links to friends, family and networks, and our held-hostage libraries and content. So what used to save us time, now consumes hours of wasted time navigating the junkyard of sites and apps littered with unwanted, deceptive, and totally fraudulent crap.

As someone both fascinated and appalled by AI, I wondered whether this new 'tool' might not just flood the pathetic remains of the internet with additional oceans of garbage, but also, just maybe, provide us with a way to work around it, to get what we want without having to actually go into it. Let the AI do the garbage-scouring for us.

The possibility for this started to become clear as AI quickly challenged, and then largely rendered obsolete, the enshittified search engines that served as our main 'portals' into the internet. Why use the ad-cluttered, disinformation-ridden, almost-unnavigable search engines satirized in the image above, when AI will (1) give us what we're looking for much faster, more easily, and more accurately, and (2) cite the sources for its answers so we can check out AI's veracity directly without having to search for it.

The big corporations and purveyors of disgusting and lying 'marketing' crap are absolutely terrified just of this development. The SEO vendors have slued furiously to abandon attempts to 'influence' (ie bias and misinform) search result rank, and are now developing tools that 'optimize' their corporate customers' appearance in AI results. If we're not careful, and fast, they'll get away with that, and AI query results will quickly be enshittified to be as horrible as search engine results.

But, at least for the moment, the open-ended nature, and immense power, of AI tools might offer another opportunity.

Suppose we developed ways to use AI to curate our networks and feeds and summarize them, with supporting links, so we completely avoid ads, clickbait, and misinformation — so they just deliver to us, 'clean', exactly what we want, and nothing else?

So AI could maintain a personal, editable, categorized list of 'trusted people' and 'trusted information sources' for us, and use it as a filter for all our AI queries. So that if I asked the AI tool "What are my closest friends up to?", or "What do my trusted sources say about the situation in Sudan (or about the subject of free will)?", or even something subtler like "Any health issues among my family or friends?" or "What are my trusted sources, and my friends' trusted sources, saying about whether multipolarity and the end of US hegemony, and the end of USD dominance, are actually happening, or are just wishful thinking?"

The AI could then scour the wasteland of social media, all the blogs, RSS feeds and other sources for us, and just give us what we're looking for — in seconds. With links if we wanted more right from the 'horse's mouth'. Never again would we have to enter the polluted waters of Farcebook or XTwitter. Put your update on your own site, anywhere, and everyone who you want to find it, and who wants to find it, will find it.

To use an analogy, AI hence becomes our 'shopper' not just our 'delivery service'. We don't have to deal with the flyers, the salespeople, the ads and marketing hype, the mis- and disinformation, and all the clutter of online 'billboards' trying to sell us crap (products and 'what you need to know' lies). Our AI 'shopper' takes our list, asks clarifying questions if needed, navigates the horrors of the web, and returns to us with just what we want.

Or, to put it another way, we can re-disintermediate the internet (as it was originally designed to be) by using our own intermediary to sidestep all the rent-seekers, profit-seekers, and deceptive 'marketers' of everything standing in the way of, and all around, what we actually want to see.

Sabine Hossenfelder has a new video about the 'dead internet', explaining what's happening as the internet becomes more and more focused on producing content for use by 'machines' (AI etc) and less and less focused on producing content for use by people.

I think the curation-and-re-disintermediation idea is an interesting possibility, but we should recognize that this will just be another skirmish in what is likely to be an extended war. Most (but not all) of the current AI tools are owned by rent- and profit-seeking private corporations, most of them desperately unprofitable and not long for this world if they can't monetize their staggering investments. They are going to fight this with everything they have, including putting ads on and in AI responses, and restricting what we can ask 'their' AI agents to do for us that might restrict their buddies' profits.

But this current crisis is the perfect metaphor for the collapse of our entire civilization. The internet has become increasingly dysfunctional and useless as it's grown larger and more complicated and corrupted. If it's not dead already, it soon will be. The question is, will we be able to salvage what's useful in it, and ignore the graveyard of corporate and political and AI garbage and mountains of clutter? Or will we just walk away from it and leave it to rot?

It's going to be interesting to watch.

image by AI; my own prompt

Often young children, puzzled or distressed by the behaviour of their peers and the other people they know, invent imaginary friends — characters who share their joys, who understand and reassure them, who have interesting things to say, and who it seems are just more fun to be around, much of the time, than 'real' people.

It's a way of making sense of the world, carrying on a conversation with oneself from a position of shared context, curiosity and understanding. A way of imagining the world as a healthier, happier, more compassionate place. A way of filling an empty space inside.

Writers of fiction are engaged in a very similar exercise. They invent characters, and make them say and do funny and obvious and quirky things. Sometimes those characters represent aspects of the writer that the writer wants to express and explore. Sometimes they are characters the writer wishes they were more like (or perhaps less like). Sometimes they are characters the writer wishes existed in real life.

These characters are not so different from the imaginary friends that young children invent, that their parents and their 'real' friends later ridicule as childish. So young children will often then 'put away' their imaginary friends, and will talk with them only when they are alone. Or not at all.

We writers have no such shame about our characters, and may even employ them in a whole series of stories, and even include ourselves as the stories' narrators.

The characters in my stories have lives that extend far beyond the page. I sometimes hear them talking to me when I'm thinking about some particular problem, or just daydreaming. They are my delightful, quirky, imaginary friends, my undemanding, wise, lifelong companions, and I don't know what I'd do without them.

We are conditioned to think that we can 'know' another person, and hence we are often shocked when the behaviour that person exhibits seems completely 'out of character'. But what we think we 'know' about other people is no more real than what we 'know' about our imaginary friends or the characters in novels, plays and songs. We make it all up, entirely from our imagination.

No one really knows who you are either, or how you think or how you feel. We don't even really know ourselves. All we can do is try to make sense of our bodies' behaviours, look for patterns, and construct them into the 'story of me'. And that story is just as imaginary as the stories we tell ourselves, and others, about who they are. And just as imaginary as the young child's stories about their make-believe companions.

And because we don't want to appear foolish to others, we nod and agree that these stories we tell and hear are true. We pretend to know ourselves and other people, pretend that we know who we are and who they are, when we're just making it all up, and looking for confirmation that what we've made up is true, especially the 'story of me' we've made up.

Part of what we love about inventing imaginary friends, and story-writing, is the feeling of control we have over our invented characters. And part of it stems, I think, from the despair we feel about our 'real' selves and other 'real' people not being quite up to what we imagine they might or should be capable of, when our imaginary characters can be and can do anything. They are 'perfectly' who we imagine them to be.

Our education system, our workplaces, our political and religious ideologies, and our peers, all pressure us and tell us we can and must be and do better, that we can be and do anything if we strive hard and long and intelligently enough (and stop 'daydreaming'). And Hollywood and literature sell us heroes who can do anything, and people who are our ideals of who we want to be, and of who we want to love. They keep us unhappy, desperately searching, hopelessly striving, and obedient.

And it's all just stories, stuff made up in our, and others', imaginations.

What if we could 'park' our unhappy 'stories of me' and recognize them as the absurd and impossible fictions they are, and refuse to 'own up' to them?

What if we could set aside our stories of who and what others we think we know are, or could be, and just be with them, if that brings us joy, and not be with them, if it does not, without judgement? What if we could just be the wild creatures we remain, underneath all our stories, underneath the fictional 'story of me'? (The cats and dogs we love might remind us how.)

And what if we could shamelessly and happily imagine new characters, dream or write them into being, characters that bring us pleasure and joy, even though they are not 'real', because they fill a little empty space inside us, and help us see through the bewildering and exhausting fiction of our own and others' stories? Why should small children and writers have all the fun?

Our imaginations can cripple us, terrorize us, bleed us dry with regrets about what might have happened, and with dread about what might happen in the future. Many unhappy people are telling us now that we (and this 'we' is never defined, but it presumably includes you and me) have to "create a new story" to replace the simple sad truth of what is happening in the world, and then we have to work furiously to make this new story 'real'.

But this is just another prescription for our continued enslavement and immiseration by stories of what "should be" and "could be", a prison of impossibilities.

Instead, perhaps, our imaginations might liberate us from these terrible stories, by letting us see them for what they are — total fictions, shit made up in our heads, not to be taken seriously.

Perhaps we could rediscover what small children and fiction writers know — that our imaginations can let us create a world of remarkable, delightful characters of our own invention, through whom we can co-create new and wonderful stories, stories that are fun, invigorating, inspiring, joyful, comforting, relieving, entertaining — and, like all stories, completely, perfectly, untrue.

Recently, many people have begun talking about the US having a k-shaped economy. In it, a handful of wealthy people are doing very well financially, while many others are falling further and further behind. I expect that the low wages of the majority of workers will soon lead to adverse impacts on businesses, governments, and international organizations. This phenomenon is likely to lead to a very uneven world economic downturn in 2026.

The world economy is subject to the laws of physics. The world economy seems to be reaching growth limits because there are too few easily extractable energy resources (as well as other resources, such as fresh water), relative to the world's population. The Maximum Power Principle strongly suggests that even as limits are hit, the world economy cannot be expected to collapse all at once. Instead, the most efficient producers of goods and services will be able to succeed as long as resources are available, while less efficient producers will tend to fall by the wayside. Thus, the Maximum Power Principle somewhat limits the speed of the world's economic downturn.

In this post, I will try to explain the challenges the world economy is now facing. I will also provide some thoughts on how 2026 will turn out.

[1] The k-shaped economy that the US and many other countries are experiencing is an indication that resources are, in some way, "running short."Humans all have similar basic needs. They need food to eat, and they need to cook at least some of this food before they eat it. They tend to need transportation services, both for themselves (to get to work) and for goods, such as the food they eat. They also need governments to keep order and to provide basic services, such as roads and schools. All these goods and services require energy of a suitable kind, such as human labor, burned biomass, or fossil fuel energy. They also require arable land, fresh water, and minerals of many kinds.

If there are not enough resources to go around, the easiest way to accomplish this is by creating a k-shaped economy. One example is with farmland. In many traditions, when a farmer dies, his oldest son inherits the farm. Younger children are then forced to find other kinds of employment, such as being a craftsman, farmer's helper, or priest in a church. Wages for these younger children can easily fall lower than the income of their land-holding older brothers, especially if large families become common. Creating jobs that pay well for all the younger children becomes a problem.

A similar phenomenon has been happening in many Advanced Economies (US, UK, and other countries included in the OECD) in recent years. Parents are doing quite well financially, but their children often have difficulty finding jobs that pay well, even after advanced schooling. Some adult children are also left with educational debt to repay. This is a new type of k-shaped economy.